2-7-2002

FAY WELDON

(N.

1931)

·

Auto Da Fay,

by Fay Weldon, Flamingo, London, 2002.

| |

Another pages about this author,

here,

and

here,

and

here |

| |

|

A palavra portuguesa mais utilizada noutras línguas é Auto da fé,

escrito autodafé (ou Auto-da-fé, título em inglês de um romance de

Elias Canetti), o processo que era movido pela Inquisição e que hoje

significa qualquer tipo de processo inquisitório. Aparece em todas as

línguas europeias, até em russo -

Аутодафе

– Ver

aqui.

Quando Fay Weldon intitula o seu livro “Auto da Fay”, está na realidade

a utilizar uma expressão portuguesa, que se pode traduzir em inglês por

“acting the life of Fay” |

|

Life and loves

Parts of her early life

were so 'insane' she can only write about them in the third person. But as

novelist Fay Weldon reveals in her new autobiography, she managed to find refuge

in patches of happiness

Emma Brockes

Monday May 6, 2002

The Guardian

| |

Except for

the few months after the birth of her first child, Fay Weldon has never kept

a diary. There was nothing to say, she says, or else there was too much to

say. Introspection was the luxury of girls from good homes. The one time she

was asked to stand up in class and read aloud her composition, it was a

recipe for bread. "Good, clear, lucid prose," she says. "But how dull!"

Weldon's

autobiography, Auto da Fay, sets out the life of a practical woman. She

lives in a house in a posh street in Hampstead, with her third husband, Nick.

Outside, the blossom flops and the foliage dangles. It is beautiful. "It is

near the tube," says Weldon. She chunters merrily. A refrain of her memoir

is, "I was happy," when the circumstances, for the most part, gave no cause

for it. The child of divorced parents when divorce was a sin, a poor single

mother, the wife, incredibly, of a schoolmaster who aspired to be her pimp:

adversity taught Weldon to find pleasure in unpromising places. Her

reputation as a woman who not so much speaks as yells her mind is at odds

with the modesty of her early years. The author of such bolts of hellfire as

The Life and Loves of a She-Devil was, it turns out, for many years

practically third party to her own existence.

On the

evidence of the interview, Weldon is not snooty or aggressive or, as she is

often characterised, cynically controversial. She has retained the

mannerisms of a woman with no confidence: quietly spoken and quick to echo

laughter. Her older sister, Jane, was identified early in life as the

interesting one and given licence to break the rules where Fay was not. "Jane

did the doing as she wished for the both of us," Weldon writes in the memoir.

"I had settled very much into doing what I ought." But on closer inspection,

her manner seems to be born of precision, not meekness. If she speaks

delicately it is to ensure that she has settled on the right word. |

|

|

She is a

leaver of long, thoughtful pauses while her blue-grey eyes search out a meaning.

"Completely practical and always precise" is how she describes her prose. "I did

always like to get the sentence right." Style, the subject of so much

pretentious analysis, is, says Weldon, "how you say what you want to say in the

shortest time available, so you can all go home". She relates this to gender. "It

is rather like the way women conduct meetings. I always find that men conduct

meetings very long-windedly, they sort of wander off, whereas women get straight

to the point, then go home to look after the children."

Weldon has

four sons, ranging in age from 23 to 46. It was after the birth of her first son,

Nicolas, that she was forced through want of alternative to marry a man named

Ronald Bateman. Her son's father, Colyn Davies, could only offer her a life as a

gas-fitter's wife in Luton. It didn't appeal and since she couldn't earn enough

money to support her son on her own (the Equal Pay Act was still 10 years off),

she accepted a proposal of marriage from a respectable-looking headteacher from

Acton, west London. It was 1957. The months that followed still alarm Weldon so

much that her memoir's narration switches from the first to the third person. "Mrs

Bateman was disgusted," she writes.

Mr Bateman was

a bully. He wouldn't have sex with her. Instead, he encouraged her to find work

as a hostess in a strip club and to sleep with other men and tell him about it.

She did it once. Then she took her son and ran away. It is such an unexpected

episode, so crazily English in its kinkiness, that I tell Weldon I could hardly

believe what I was reading. "Well I couldn't really believe I was writing it,

which is why I went very swiftly into the third person." When she speaks of

herself, it is largely in the second person, the writer's habit of turning her

life into narrative. "What is so odd is that until you wrote about the

experience, you didn't really see it. The extraordinariness of it escaped you

because it always does when you're living through something. It's only

afterwards, when you look at little patches of your life, that you realise that

it was absolutely insane."

She got

through it by taking refuge in small flashes of happiness. "You get up when you

want, you put on a cup of tea, you make a slice of toast, you dance around with

the baby and it's lovely and then hubby comes home and night falls. It's

absolutely fine, so long as you don't see it in a context, which people are very

good at doing when they're in a rather murky part of the forest." Because she

had grown up in New Zealand, where nothing ever seemed to happen, there was a

part of being Mrs Bateman that Weldon found powerfully fascinating. "Always! Yes,

always! I wanted to see more, it was part of being alive. If you're in New

Zealand, you feel that the real world is just around the corner - or a long way

round the corner. You're so far away, you want to know everything."

This was not a

case of her collecting life-experiences to put in a novel. Weldon had no idea

she could write fiction until she was well into her second marriage, to Ron

Weldon, an artist and antiques dealer, the anti-Bateman. Before that she had a

successful career in advertising, when she famously wrote the slogan "Go to Work

on an Egg". The brevity of her style owes much to those years as a copywriter.

She was happy in this period, until she tired of hanging out in the corporate

bubble. "The bubble's fun, the bubble's very seductive, the bubble has friends.

But I think I always knew ... it was always something I knew I would have to

leave. You would occasionally be in the elevator and look around and think:

really, if this lift suddenly plummeted to the ground and we all died, the world

wouldn't miss a thing." She laughs uproariously.

Feminism, says

Weldon, never properly addressed the issue of motherhood, short of advising

women not to go into it, and of working mothers in particular. She is a feminist

of the old school against whom the likes of Naomi Wolf are held up and found to

be a bit drippy. Weldon has got into trouble for talking against the orthodoxy,

blaming aspects of feminism for undermining boys' confidence (although only, she

says, because she was asked, and besides, "If everybody likes something, you've

failed. Consensus is not what you're after"). She agrees with the hot new heresy

that having kids young is a good idea. Weldon's reasoning, however, is unlikely

to be folded into the conservative backlash. "Oddly enough," she says, "having

children young sort of gets it out of the way. It's very good for you in so far

as it develops your character. You realise how horrible you are. Otherwise you

go on thinking that you're a nice person. When you have children you realise

you're selfish and lazy, manipulative, bad-tempered and horrible, or just like

your mother. What you don't want to do is be doomed to stay at home and look

after them for the rest of your life, thank you very much."

The sacrifice

mothers make in their careers is, for Weldon, a bit of a moot point, since she

believes "most careers are people engaged in doing something that means nothing

to anybody". Besides which, she says, "Most women don't have careers, they have

jobs. They're told they have careers, because that suits the employers. 'Career'

is such an artificial concept. It's just people up there making money out of

people down here, I'm afraid." Weldon's concept of 'career structure', the drone

mentality of crawling up the ladder, was talked about at the dawn of feminism as

a male behavioural model into which women were uneasily forced. It may be so.

But unless you happen, like Weldon, to be talented in some jazzy creative way,

it is rather hard to avoid. Her contempt for hoodwinked career women sounds

misleadingly smug because, generally, she is not. "I always thought that I would

be discovered as a fraud," she says, "and I still feel that, and that strikes me

as one of the differences between men and women in jobs. Women think that they're

about to be unmasked."

The feeling of

fraudulence did not diminish with Weldon's growing fame, although she did gain

some satisfaction from avenging the slights endured by her mother Margaret.

Margaret's family of artists and bohemians disapproved of her marriage to Frank

Birkinshaw, a doctor, and her subsequent move from London to New Zealand. When

she came crawling back, practically penniless and alone but for two fatherless

children, she was the victim of much condescension. Weldon turned round the

family fortunes. "Fame is a very odd word which doesn't really seem to apply,"

she says, "only in that you get the vague thought you shouldn't go out with your

tights laddered."

She gets

occasional gusts of anger. As a timid child, she amazed herself one time by

instinctively standing up for a girl in the class who was being bullied. "It was

like Salman Rushdie, oddly enough. It was just the same feeling when everybody

was having a go at him. The English establishment were absolutely abominable. In

essence they all said, with one voice, 'He's a bit foreign, he's not really one

of us, and he has brought us trouble.' And I thought that was absolutely

disgraceful. Disgraceful."

The

contradictions in her character are not something Weldon wastes too much time

thinking about. The fashion for self-examination appals her. She describes a

James Thurber cartoon in which a woman is crouching on the bed, slightly

animal-like, while her husband says to her, "But what do you want to find

yourself for ?" Weldon loves this joke. Searching for one's "inner self" is, she

believes, a doomed enterprise. "There are hundreds of you, there's not an inner

person that you can find, that is truly you, that has been distorted by other

people. You are the sum of those distortions. They shift and change all the time

and so they should. I wrote a novel called Splitting, which had different

endings in the European and American editions. Because they see personality so

differently in America. The European version concludes that if you strip away

your neuroses, there's just a shadow that no one can perceive, a wraith wrapped

around the banisters. In the US version, if you strip away the neurotic

personality you're left with a strong powerful vigorous identity, a young woman

who goes off to music college. I much prefer the European ending. If you think

about it, we should enjoy our neuroses rather than find some bogus thing 'underneath'.

It's just dull. But somehow in the States, all problems have a solution. Here,

we are much more prepared to live with uncertainties, impracticalities and bad

plumbing."

Auto Da Fay

ends at the point at which Weldon attains respectability and, consequently,

becomes less interesting. Her neuroses change but do not diminish. She will

never be good with money (people who hoard money tend to be those who have

always had it, she says). "As a kind of bonus, you found you could do this thing,

you could write, and it was much easier than you ever thought and there was an

exhilaration. And then a whole set of other problems were created. So you haven't

lost your problems, but they are not as basic as where and how are you going to

live? You are lifted up. But you don't forget."

Fay and

fortune

Fay Weldon's

autobiography, Auto da Fay, is engrossing. And maddening, for she prefers

fiction to real life

Kate Kellaway

Sunday May 5, 2002

The Observer

Auto da Fay

Fay Weldon

Flamingo £15.99, pp366

| |

When Fay

Weldon leaves St Andrews with an MA in economics and psychology, she takes

her scarlet university gown with her: it comes in useful later, she says, as

a Father Christmas outfit, before moths claim it. The scarlet gown is

perfect Weldon garb - it sums up the teasing personality behind her

autobiography, Auto da Fay. How much of what she writes is serious-minded

and educated - how much a festive charade?

The

delight of Fay Weldon is that one can seldom be absolutely sure if she is

serious. She has always been anarchically clever, funny, fearless, a

one-woman-show. As a child, she was the Cheerful Person in her family. When

her sister took up with an unsuitable man, her mother leant on Fay. 'To be

cheerful was my accepted role around this time, and come to think of it,

always has been and still is.' (She is full of afterthought.) |

|

|

|

Weldon doesn't

let the reader down any more than she did her mother in this frustrating,

engrossing, lazily entertaining autobiography. It is the sort of book stuffed

full of things that you hope are made up but fear are true. I flinched at her

description of the way toads were once used in pregnancy-tests and cannot banish

the description of the chef in a hotel where Weldon worked who used to blow his

nose into the whipped cream when angry.

But Auto da

Fay begins before the beginning, in the womb, in New Zealand. When her mother

was pregnant with Fay, they survived an earthquake (might this explain Fay's

enduring taste for drama? Her first short story was set in Pompeii). The New

Zealand of childhood is sketchily remembered: the 'inspiring' cakes seem to have

hung on most vividly in the mind, the friendships second, the landscape third.

Weldon's mother and grandmother were English: 'bohemian' literary, musical,

fragile - not obvious candidates for robust antipodean life. Her father was a

charming doctor who liked the heat (or generated it in others, especially women).

The book's

structure is slovenly, as if rambling at speed and the text itself seems

unedited. But repetitions are telling: Weldon confesses (several times) that she

does not like watching horror movies at home (the devil must not be invited in),

she tells us (twice) about her rejected advertising slogan: 'Vodka makes you

drunker quicker' (tempting to repeat that one, I can see); and she boasts three

times that her grandmother, Nona, lived to 99 (this greatly appeals to her).

It would be

surprising if it didn't. The amazing thing about this book is the degree to

which Weldon believes family history repeats itself. Life is a game of

Grandmother's Footsteps. Hand-me-downs rule. We are no more than our ancestors'

cast-offs. Her belief in patterns is superstitious: 'the lost wedding ring turns

up on the day of the divorce; the person you sit next to on the Tube happens to

be your new boss.' She has seen ghosts, of course.

If this were a

conversation and not a book, one would want to keep interrupting to ask more

about what she felt, more about what her family was actually like. For someone

so garrulous she is emotionally guarded, admitting - tantalisingly - that she

prefers to look outside herself. The exception to this is her outburst of grief

over the death of her friend, Flora. And, at one point, over 100 pages in,

without warning (everything she does is without warning) she grumbles furiously,

as if it is all the reader's fault, that she is not finding writing her

autobiography therapeutic.

She solves the

problem by writing as if her life were fiction. She describes engagingly the

romance of living in a houseboat on the Thames as she did for a while and the

feckless charms of the father of her first child. She resorts to the third

person to relive her marriage to a schoolteacher, Mr Bateman, whom she married

out of miserable expediency (for her son's sake). Mr Bateman sounds like a

figment of her imagination, a bad dream. He acted as a nervous pimp, guilty

about his sexual non-performance, finding her other partners. She grew fat and

became source material for her first novel The Fat Woman's Joke. Narrative, for

Weldon, has always been a cure.

The

autobiography ends as her writing career begins. I was left musing over an

unacknowledged pattern in her life that is too strange - and revealing - to

ignore. It is to do with her tendency to look down (rather than back), her

interest in what goes on at ankle level and below. She describes her father

walking off down a beach, abandoning her family for good. This leads on to a

description of a chained magpie who pecked her ankles. When she has a crush at

school, it is the girl's pixie-ish footwear, not her face, that enraptures her.

Anxiety is like a fox that 'snapped at her heels' and babies, she warns, grow

into children who 'run around your ankles and bite you'.

Ron Weldon (to

whom she was married for 31 years) may be responsible. On their first date, he

told her to 'keep looking at the ground' as you never knew what you might find.

He then conjured a £5 note from the gutter.

This much I know

Fay Weldon, 70, writer, on the lessons she has learnt in life

Jonathan Heawood

Sunday May 12, 2002

The Observer

There's a time and a place for everything - even incest and morris dancing - in

fiction.

Therapists say you should

learn to live independently after a break-up: not rush into another relationship.

Are they mad? Turn your back on God's gift and it may never come again.

Children will call their

teacher a fascist because he makes them do things they don't want to, and Hitler

called himself a socialist. I'd always prefer a funny fascist to a serious

socialist.

When I arrived in London I

saw the city as a challenge. I think I've won.

In autobiography you put a

kind of shape on to the life. In the first half you set all the questions, and

in the second half you answer them.

Which came first, chicken or

egg? The egg. You can't go to work on a chicken. Of course I didn't write Go To

Work On An Egg. But it's a long and boring story and no one has the patience for

it - not even me.

Yesterday's boys are today's

girls, guarding their sensibilities and their virtue against predatory attack,

demanding commitment, affection and babies.

True creative freedom is

these days reserved for children's authors, their editors silenced and their

marketing departments struck dumb by the unexpected success of Harry Potter .

The media wears you out,

there's so much of it. But it's our only protection against government.

People long for literature to

be pure and writers to live in garrets, but someone has to do it, someone has to

be morally responsible for society, and the bishops are a bit flaky these days.

Yesterday's truth is today's

lie. Ibsen gave the process 20 years and he was right. Feminism started as a

revolution, succeeded, and turned into an orthodoxy.

I once killed two friends of

the family by putting them in a swimming pool with a diving board but no way

out. I could get addicted to playing The Sims, although the game is limited by

the imagination of its creators. They have a suburban idea of luxury.

I know that I'm a real writer

because sometimes I write a short story just because I want to; not because

someone's told me to.

Nothing stops me writing

except flu.

A little recognition always

goes a long way. Getting my CBE was like a school prizegiving. We stood in a

queue with the other great and good, and we chatted a lot and were asked to be

quiet by the footmen. (It is possible for the great and the good to become

extremely noisy.) The Queen said: 'I believe you write television plays,' and I

said: 'I write anything I'm asked, Ma'am.' I have been a royalist ever since.

Women always feel the need to

apologise for the weather, as if it was their fault.

I write in short paragraphs

because when I began there were always children around, and it was the most I

could do to get three lines out between crises.

Learn to write with a

computer. I've only recently begun to use a keyboard. It happened because I read

one of my own stories in an anthology of mostly American writers, and my

handwritten piece seemed gnarled and twisted compared to the easy flow of the

other writers who I realised all used computers. So I decided gnarled and

twisted was not the path of the future. I've yet to see if it makes much

difference to my style.

I would write another

sponsored novel [like The Bulgari Connection] if the opportunity came and I

could do it with a degree of integrity. A young male Belgian writer has just

finished a book sponsored by Harley-Davidson and is getting rave reviews, so it

can be done, but not often. Companies have to choose their writer very carefully.

The only historical figure I

identify with is Patient Grisel in The Canterbury Tales - a forlorn and

self-pitying figure who came to a bad end.

I crave nothing but constant

love and attention.

World in Acton

(Filed: 12/05/2002)

Lynn Barber reviews Auto da Fay

by Fay Weldon.

FAY WELDON started life as

Franklin Birkinshaw in Birmingham in 1931. Her mother, Margaret, called her

Franklin because she worked out by numerology that the name "came out the same"

as William Shakespeare. Soon afterwards, Margaret rejoined her husband Frank, a

doctor, in New Zealand.

Margaret was beautiful, bohemian,

fey. She read horoscopes, painted tarot cards, saw visions of angels in the

park, and wrote novels under the nom de plume Pearl Bellairs - the name of the

vapid novelist in Aldous Huxley's Crome Yellow. She was singularly unsuited to

being a New Zealand doctor's wife.

And, indeed, she wasn't for long.

The marriage was unstable from the start - husband and wife took turns to

disappear, and Fay and her sister, Jane, spent much of their childhood being

shuttled between parents in hotels and boarding houses. Frank was constantly

unfaithful, but when Margaret retaliated by having an affair he divorced her for

adultery.

Fay and Jane then lived with their

mother in Christchurch and spent the summers with their father in Auckland. But

when Fay was 14, her mother inherited a small legacy and returned to England on

the first ship after the war. Her father waved them off and Fay never saw him

again - he died of a stroke as she was starting university.

At St Andrew's she discovered sex

in a big way and acquired a reputation for "putting out". This was during the

Fifties, when good girls didn't. Jane married an artist and got pregnant, so Fay

promptly got pregnant, too - but without the convenience of a husband. The baby's

father wanted to marry her and said he could support her by being a gas fitter

in Luton, but she didn't fancy being a gas fitter's wife. So she moved to

Saffron Walden to have the baby, and tried to start a tearoom. This failed when

she decided that the house was haunted - Weldon seems to get ghosts the way

other people get mice - and moved back to London.

At this point, for reasons that

she says are mysterious even to her, she married a divorced schoolteacher 20

years her senior called Ronald Bateman. Her two years as Mrs Bateman in Acton

sound quite extraordinary - her husband didn't want sex but he wanted her to

have sex with other men and tell him about it. She obliged once or twice, and

worked as a nightclub hostess at his instigation. She also took part in

foursomes with a friend who worked in advertising.

One day the first Mrs Bateman rang

Fay to explain that the reason he married her was that he always put "married

with son" when applying for headmaster posts, so he needed to be able to produce

a wife and son at all times. And indeed when Fay left him after two years, he

immediately acquired another unmarried mother with son.

Once Fay's son started school, she

was able to work, and she zoomed to the top in advertising with such deathless

slogans as "Unzip a banana" and "Go to work on an egg". At last she was able to

support not only herself, her son and her mother, but sometimes her sister's

three children when Jane had one of her periodic nervous breakdowns. Fay says

she was always the efficient one, and the sanest of her family.

At 29, she met the antiques dealer

Ron Weldon "and that was that for 30 years". While pregnant with their first

child in 1963, she wrote a television play - by hand because her husband didn't

like the sound of typing - and became Fay Weldon the writer we know and love.

Auto da Fay ends at this point, saying: "What I do from now on, all that

early stuff digested and out of the way, is write, and let living take a minor

role."

It is an astonishing story,

lightly and deftly told, without self-pity but also - frustratingly - without

introspection. Always, at what should be the crucial moments of her narrative,

she seems to skip away and start babbling about ghosts or Sylvia Plath or

anything, it seems, except the key question for an autobiographer - what was

going through her mind. She remarks at one point that, though often called upon

to give literary prizes, she seldom wins them and she likes to think it is

because the shortness of her sentences "makes the books appear to lack gravitas".

Actually, I think it's the lack of

gravitas that makes the books appear to lack gravitas: she prefers teasing to

truthfulness. As for her style, I cannot see how any professional writer could

re-read a sentence like "We lived on a knife-edge, financially and socially: we

knew better than to rock the boat" without deciding that either the knife-edge

or the boat (preferably both) would have to go. Even so, Auto de Fay is

gripping. It will delight Weldon's many fans and keep the book clubs happy for

months to come.

A muddle turns into a morality

tale

(Filed: 12/05/2002)

Anne Chisholm reviews Auto da

Fay by Fay Weldon.

LIKE all autobiographers, Fay

Weldon, one of the most prolific, entertaining and provocative of contemporary

women writers, has sought to make retrospective sense of the muddle and

unexpectedness of life.

Now rising 70, she has always

drawn openly on her own experience for her sharp, funny modern morality tales;

her autobiography reads like a first draft (it is surprisingly unpolished and

studded with repetitions) for one of her novels, full of embattled, resilient

women and selfish, unsatisfactory men. Again like her novels, the surface

sparkles along merrily enough, but there are darker currents beneath.

When she was still in her mother's

womb, in New Zealand in 1931, a serious earthquake flattened the town where they

lived, portending, Fay Weldon suggests, future dramas and upheavals. Certainly

life for her family and herself was never to be settled or easy; luckily, they

were an unconventional and adaptable lot.

Her parents were both English,

recent arrivals in New Zealand; her father a doctor with literary leanings and

socialist opinions, and her mother an aspiring writer. The marriage was stormy;

Weldon - christened Franklin Birkinshaw and nicknamed Fay - was born in England

during one of several separations. Eventually there was a divorce, and in 1946

Weldon, aged 15, moved back to England with her mother and sister Jane. She grew

up loving her father but unable to trust him.

Hovering over the whole book is

the eccentric, bohemian figure of Weldon's maternal grandfather, Edgar Jepson,

author of 73 "light but popular" novels, believer in Free Love and the occult.

From him, Weldon strongly suggests, may have come her ability to write clear

prose and her tendency to believe in omens and see ghosts. She also ascribes

much family unhappiness to the pattern set by his sexual misbehaviour; Free

Love, she remarks, has always been an excuse for "hurtful activity", and the

ones hurt are usually women.

Postwar Britain was bleak, and

very unlike the expatriate's fantasy of home. Money was desperately short; they

moved from one cheap flat to another while Weldon's gallant, original but wildly

impractical mother tried to make a living . But somehow Weldon, who was clever,

found her way to university at St Andrews in Scotland, where she got a degree in

economics and psychology and discovered sex.

Back in London and taking a series

of odd jobs ( including a stint as a Foreign Office researcher) she describes

herself, in a curiously old-fashioned phrase, as a "lost girl", looking for love

in affairs with unsatisfactory, often married, men.

When she became pregnant at 22 she

refused to marry the father but agreed, at her mother's urging, to change her

name by deed poll. The struggle to keep herself and her child proved too much

for her and she gave in to marriage with an apparently respectable schoolteacher,

who turned out to be sexually inadequate; he encouraged her to work as a

nightclub hostess and report on her affairs with other men. As soon as she could,

and when she had found lucrative employment in advertising, she left.

Famously, Fay Weldon coined the

slogan: Go to Work on an Egg. Here again, she points out, she was following in

her grandfather's footsteps: during the First World War he came up with the

slogan: Eat Less Bread. She did well in advertising, and made friends among the

other aspiring writers and poets who were her colleagues. In 1961, at a party

full of Hampstead intellectuals, she met Ron Weldon, artist and antique dealer,

and fell truly in love. She married him, had the second of her four sons, and

started to write her witty, subversive, increasingly successful novels.

The book ends here, with Fay

Weldon the writer finally at the starting post. After all, she tells us, she

learned how to make painful matters amusing in the playground of her school in

New Zealand, and, for good or ill, "I have never stopped".

Anne Chisholm is writing a Life of

Frances Partridge.

The life and loves

of Fay Weldon

(Filed: 02/05/2002)

The autobiography of Fay Weldon,

published this week, is a spiky read. Its author talks to Nigel Farndale about

sex, psychiatry, self-loathing and her early career as a hostess in a Soho clip

joint

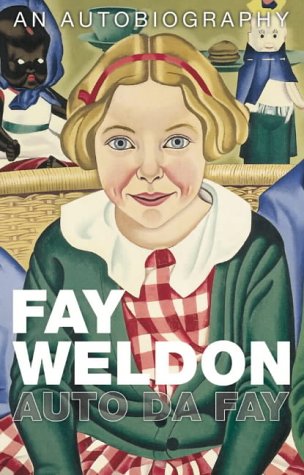

A RISKY business, capturing the

essence of a seven-year-old on canvas - especially when you then have to show

the painting to the child's mother. Rita Angus, a New Zealand artist, managed it

when she painted Fay Weldon in 1938 - really dipped her paintbrush in the murky

stuff of her sitter's 'inner soul'. Fay's mother Margaret, a novelist who was

living in New Zealand at the time, hated it; thought that with its hard edges

and simple colouring it looked like a caricature. When she returned to London

with her two young daughters - following a messy divorce in which both parties

admitted to infidelity - she tried to leave the painting behind.

A friend ran to the dock with it

just as the gangway was rising, shouting, 'You left this!' Margaret considered

throwing the painting in the sea but asked the friend to return it to the artist

instead. It now hangs in the National Gallery of New Zealand.

In the painting Fay sits beside

Jane, her older (by two years) sister. Both are wearing gingham dresses with

white collars and ribbons in their hair. When I meet Fay Weldon - now 71,

married for the third time, mother of four sons, author of 24 novels, most

notably The Life and Loves of a She-Devil (1983) - at her home in Hampstead, she

is wearing Nike pumps, black trousers and a black top. But I recognise instantly

the girl in the painting. It wasn't a caricature, after all. She still has the

same icy-blue saucer eyes, the same moon face, the same high, pouchy cheekbones,

the same bob of pale blonde hair. Her skin is still smooth, too - or smoothed,

thanks to the tucks and nips she blithely admitted to having a few years ago.

Even her hunched shoulders and no-neck posture are the same. Her expression, now

as then, is one of mischief masquerading as innocence.

She takes a sip of coffee from a

mug with himself written on it - her hand shaking slightly - and tells me why

she has reproduced the Rita Angus painting on the dust-jacket of her

autobiography Auto Da Fay, which is published this week. The book is partly

about what she calls the 'survival unit of three': her mother, her sister and

herself. 'Writing about Jane helped me come to terms with her death [from cancer

at the age of 39 in 1969]. At the time I felt total helplessness in the face of

it. I had to be elliptical, though. Her children don't know the extent of her

illness. You can have too much truth.' You can see why she might think that. The

truth or facts of her autobiography can seem rather too much. Among other things

she reveals that, as a young woman, she flirted with prostitution and worked as

a hostess in a Soho clip joint. She thought herself plain and dull, she writes,

or at least that is how her mother made her feel - but she soon learnt that it

wasn't beauty men were after, but availability. 'Sit on a bar stool in a skimpy

dress and look like you charge for your favours and perfection of leg doesn't

matter.'

One could be forgiven for wondering if these episodes have

been included simply because she thought they might help sell the book, even if

she does feel they represent 'too much truth'. After all, she first found

success not as a novelist but as the advertising copywriter who coined the

phrase 'Go to work on an egg'. She knows how to sell a product, in other words.

This commercial sense was demonstrated admirably by the press coverage she

generated for the launch of The Bulgari Connection last year. It was, she calmly

announced,

a product placement novel sponsored by the Italian jewellery designer Bulgari.

There were howls of indignation from the literary world, who accused her of

selling out and compromising her integrity. She just shrugged and said, 'Have I

betrayed the sacred name of literature? Well, what the heck?' And when another

book, Big Women, about a feminist publishing house in the 1970s, was published

four years ago, she caused a storm by making the rather non-feminist comment

that rape is not the worst thing that can happen to a woman. 'No,' she says now

in a soft, breathy voice. 'These things stir themselves up, it's not me. And I

don't think they help with sales. If you were more mysterious and difficult as

an author people would feel they had to read your books.'

Did she find it therapeutic to

write about her youthful follies, then? 'Cathartic maybe, which I do not believe

is therapeutic. Things are not made better if you face them. They are just

reactivated. I'm all for denial. It's a tried and tested survival mechanism.'

She examines her nails. 'And yet if things happened in your life, you should put

them in your autobiography - even if life is less believable than art. When you

make things up in a novel people recognise themselves and try to sue you for

using their lives. They assume everything they do is unique. Yet we all have

much in common.'

I can't believe that many people

would have had marriages in common with hers. 'I suppose my marriages were

unusual,' she says with a gentle laugh. She is now married to Nick Fox, a jazz

musician and poet 15 years younger than her, who has popped his head - bushy

eyebrows, clipped beard, a cigarette between his lips - around the door to say a

friendly hello. They married days after she divorced Ron Weldon, her second

husband, in 1994. Ron, a jazz musician and artist, had been in psychoanalysis

for ten years before he met Fay and soon persuaded her to take it up as well. 'Both

Ron and I went to see our analysts twice a week so really there was no need to

speak to each other,' she recalls drily. The marriage came to a sudden end after

30 years when, Fay claims, Ron switched to an astrological therapist who told

him that the couple had incompatible star signs. Eerily, on the day their

divorce was finalised Ron died of a heart attack.

But her marriage to Ron was

straightforward compared to her marriage to Ronald. In 1956 she married Ronald

Bateman, a headmaster at a technical college in west London who was 25 years

older than her. She was a bohemian single mother not long out of university (St

Andrews, where she read economics and psychology) and needed a roof over her

head. 'Poor Ronald Bateman,' she writes in Auto Da Fay, '[I] was a heartless,

practical monster.'

'But actually it wasn't so unusual,'

she tells me. 'Marrying for convenience happened a lot. Most girls who got

pregnant had the baby adopted or they had a shotgun wedding. Or the girl's

mother pretended to be the mother, so the child grew up thinking her mother was

her sister. Extraordinary the lengths people went to to be respectable. When I

wrote about that episode I did have a reaction. I was filled with self-pity and

did think, "Poor little thing. What a stupid child."'

She had decided, she says, to

donate her sexual and domestic services in exchange for bed and board. Ronald

Bateman didn't want to consummate his marriage, though, he just wanted 'wife and

son' on his cv. Instead he offered his wife to his friends, telling her if she

wanted to find a lover he wouldn't mind. A 'mean-eyed' stallholder in the market

then offered her a pair of stockings in return for sexual favours; she told

Bateman who then vetted the man. She arranged to meet the stallholder, found

herself trapped in his front room, was stripped, humiliated and forced into 'painful

and unwanted' sex. Then, while she wept, he gave her the stockings.

Is Ronald Bateman dead? 'Yes.'

Phew, in a way. 'Yes, but I felt

bad because he isn't around to put his side. It wasn't really his fault. Almost

nothing is anybody's fault, you come to realise. Everybody thinks they are doing

the right thing.'

I get the feeling from reading her

memoirs that she is amoral, or at least a morally ambivalent person. Is this

fair? 'Morality tends to be what you can afford. It's like when I was in

advertising and refused to work on a tobacco account. Had I not been able to pay

the rent at that time through writing I might not have made such a principled

stand.' She absent-mindedly plays with the beaded neck chain attached to the

arms of her Armani spectacles, coiling it and uncoiling it on the table. She

sighs. She frowns. 'To do things to your own advantage and at someone else's

expense seems an offence to one's own dignity, so better not do it. I think that

is my position.'

What about when she accepted the

silk stockings in return for sex? 'They weren't even silk, they were nylon!' She

gives a snuffly laugh. 'That was just masochism.' She had low self-esteem? 'Of

course I had low self-esteem! No, I had a labile sense of self-esteem, sometimes

very low and sometimes very high. The masochism was deeply ingrained in my

psyche, as it is in all women. That is where the pleasure lies.' She stares out

of the window. 'I'm not going to bare my soul completely but, of course, I was

depressed.' One manifestation of this depression was her comfort eating - which

later became the subject of her first novel, The Fat Woman's Joke (1967).

'I wasn't happy because I felt I

was wasting time,' she explains. 'I wasn't cut out to be a suburban housewife in

Acton.'

Was her self-worth affirmed by

having sex with strangers? 'Yes. Intimate congress with another human being is

very reassuring. It makes you feel alive and worthy of their attention. It's

like a drug. Heroin addicts enjoy the pimples and the dirt and the syringes and

the self-disgust. The debasement is part of it.'

Her father Frank, an English

doctor with a practice in New Zealand, died of a stroke in 1947. She never

mourned him properly, she tells me, and she thinks this may be why she always

ended up marrying men who were, in different ways, like her father. 'Yes, that's

right,' she says, pronouncing her 'r's as 'w's. 'No, no, that's not right at all,'

she adds, demonstrating another verbal quirk, a tendency to instant

self-contradiction. 'I think I always married my mother. Women are supposed to

marry their fathers but actually the temperament of those they marry tends to be

more like that of their mothers.'

Fay's mother is a redoubtable

woman. Once, when she came across a poem that Fay had written as a teenage

schoolgirl - revealing an innocent crush on another girl - she overreacted

wildly and declared that she had always suspected her daughter was a lesbian. 'I

didn't understand what she was talking about,' Weldon recalls in her memoirs,

'or how I had suddenly become so loathsome: to be a lesbian was something

perverse and horrible, not just something you did but what you were as well.

Next day, on the No 9 tram coming home from school, I contemplated suicide -

wondered how to set about it.'

Was it the sort of suicide fantasy

teenagers are prone to, or had she been serious? 'Suicide has never seemed to me

to be anything other than a rational response to the world,' she says with an

incongruously fluffy laugh. 'It's mad not to be suicidal if you have a sense of

the futility of life.

I don't think it was a romantic

fantasy. Perhaps it was. I don't think it was depression, though. It's like

everyone saying Sylvia Plath [who was a friend of Weldon's] killed herself

because she was depressed. She didn't. She killed herself because she was

unhappily in love. Somebody [Ted Hughes] had spurned her. This is unhappiness,

but it's not madness.'

Surely love is a species of

madness? 'True. And therapists would say love is neurotic dependency, but what

do they know? You have a whole range of emotions: some are pleasant, some

unpleasant, but you need them both because, if you dampen one, you dampen the

other. My quarrel with therapists is that they want to iron out emotions, render

everything down and leave you with a lot of soupy feel-good - and that is only

half living.'

Her own family's emotions were

decidedly unironed. An aunt of Weldon's (Faith, her mother's sister) and her own

sister Jane both spent time in lunatic asylums. Given the hereditary nature of

some mental illnesses, did Weldon ever worry for her own sanity? 'No, I never

felt I was losing my mind. I was too practical. Yet other people worried. And I

suppose I have worried myself about patterns of behaviour. Maybe I am just in

denial.' Smile. 'When I was growing up, insanity was the great dark fear of the

age. Speaking openly about madness was not fashionable. We were more

superstitious about words. If you didn't use them, they didn't come true.'

It is often said of Fay Weldon

that, in the 1970s, she was a leading light of the women's liberation movement,

though no one can quite remember why. A few years ago, when she had a book to

promote - naturally - she caused a stir by saying that she had changed her mind

about women, and men. They weren't so bad after all? 'Men became OK. My position

was reasonable in the 1960s and 1970s. It was a patriarchy, and men did abuse

their power and spend their time despising women. It was a dreadful and

humiliating time to be a woman. You see it in extreme example in the Taliban -

the basic male attitude was not that different. But as soon as women began to

earn proper wages and could control their fertility through the pill it all

changed. To blame men now seems to be foolish. Women now talk about men in the

same language men used to talk about women. Their only defence is that men

deserve it because they were so horrid to us in the past.'

Did her attitude to men also

change because she is now happily married and she wasn't then? 'Yes, how could

it not be?' she asks airily. 'Nevertheless, I think there is enough truth in my

position for me to universalise it.' Well, she's never been afraid of doing

that. 'No, I haven't.

I sometimes take extreme positions

because I want to be argued with, to see whether my position is defensible.

Instead, you often get dismissed with people saying, "Pish and tosh, who does

she think she is?"'

When debating on radio or

television she can seem nonchalant to the point of woolliness, but also

fearless. Is this an affectation? 'In my personal life I shy from confrontation

all the time. I can't bear to have a cross word with anyone - which is rather

foolish.'

But I have read that her husbands

always complained she was too argumentative. 'Yes, they did, they do. I don't

think I am, though. It seems to me I am just putting facts forward, and when

people disagree with them, which they should do, then I moderate them.'

So is she just dressing up opinion

as fact - which is a rather arrogant thing to do? 'Entertaining,' she corrects.

'When I do get into trouble it's because I have abandoned truth for the sake of

a witty reply. I do talk more than most people so I am bound to have a higher

percentage of foolish remarks, like poor George W Bush.'

Did her time working in

advertising leave her feeling cynical, in the sense that she learnt how easy it

is to get away with lying? 'No, I believed every word of it. I'm very good at

self-deception. I like the material world. I like the difference between one

washing powder and another. I could enthuse about eggs because I thought they

were rather wholesome beautiful things.'

There is something of the

insouciant, easy-natured dilettante about Fay Weldon. She doesn't believe in

doing much research: if something feels right, she thinks, it probably is. When

she worked as a television scriptwriter - for Upstairs, Downstairs among other

things - she would submit a first draft, wait to be asked to make changes, do

them, deliver them and when she was asked for yet more changes, as she knew she

would be, she would deliver the first draft again: as that seemed somehow

familiar, it would, she says, be accepted at once. She is moreover, by her own

admission, in possession of low taste - very much a gold taps, kidney-shaped

dressing-tables and country and western music person. In her autobiography she

comes across as a strange mixture of laziness, decadence and frivolity, a

capricious yet rackety intellectual who is easily bored. Is it a true account of

her life?

'We all delude ourself about

ourselves. One paper [a mid-market tabloid] yesterday said I was "a heartless

scheming bitch". No, what was it? "A monster." That's OK. I can live with that.

There is an element of total irresponsible frivolity to me. But that may just be

my mother's view of me.'

Her mother was her opposite, a

serious woman? 'Extremely!'

Would Fay Weldon like to be taken

more seriously? 'No, I wouldn't survive. At all. So, really, my frivolity is a

defence mechanism. My sister was the serious one. I was the youngest child who

couldn't do anything but charm and chatter on merrily.'

And, as we have seen, contradict

herself without blushing. She will make reckless assertions only to laugh them

off later and she has no real consistency of thought: she used to be a

freethinker, but as of two years ago she is a regular churchgoer (C of E); she

was once very pro-therapy, now she is very anti; for a long time she believed

passionately in ghosts, now she dismisses them as mere projections; she still

considers herself to be an old-fashioned socialist yet, by her pronouncements on

the purity of advertising and her endless quest for book sales, it is obvious

she has now reconstructed herself as a capitalist. 'Of course,' she says,

another conversational trope. 'Of course people are contradictory. I see no real

virtue in consistency.'

An English teacher, a friend of a

friend, once said she had a shallow personality: was he on to something? 'No.

Absolutely not. On the contrary. I think it was because I would just sit and

smile sweetly under attack. I wouldn't burst into tears or react. So they would

just dismiss me.' Does that make her manipulative? 'Yes of course. I hope so.'

She purses her plump lips. 'No. No, I do not try to manipulate or blackmail or

put thoughts into people's heads. No. I think I'd get on much better if I did.

But I can't concentrate for long enough. My mind keeps reverting to fiction.'

She coils her beads on the table

again. 'I think women who didn't have father figures are bad at flirting and

being manipulative because they never learned to use their fathers to do their

mothers down. I was no good at competing. At the sign of any competition I

left.'

As a child she once accused

another child of throwing sweets at her and wept until a nurse came to comfort

her. 'I knew it was an accident but preferred to be miserable, for the sheer

drama of it. Later in life I'd treat lovers and husbands this way. Taking

offence and suffering - knowing in my heart that they aren't to blame, that I

just wanted a drama, my turn to be victim.'

Is she difficult to live with? 'I

do often go into a world of my own and my children do complain of that and bang

the table and shout: "I'm here, I'm here, I'm here."'

In 1996 her son Tom, then 27, was

caught in possession of 15,000 Ecstasy tablets in Amsterdam. He was given a

three-year prison sentence. Did she feel responsible? 'Of course, I wonder

whether I should have done this or that, but I didn't and I couldn't, and

actually it worked out well. It did him a power of good. Prison works in

Holland. They thought he was a genius. He started to paint and learn computer

graphics, and came out and slipped benignly back into society. But, of course,

you worry.'

She believes it is impossible to

be a good writer and a good mother at the same time. 'It is. Of course it is.

And I would always be a good writer. I sometimes sent my children out in odd

socks.' She smiles. 'Being a good mother is often a matter of public display.

The Jungian view is that the child is born perfect and it is the mother who

determines its character and, if it goes wrong, then it is the mother's fault.

This is a terrible burden and I can understand why the birth-rate among

professional classes has fallen. Who would embark on such a task?'

Her novels tend to be dark satires

on the battle of the sexes. There are few sympathetic men in them, indeed most

of her male characters are callous and idle. 'I started writing because I felt a

female view of the world should be registered. I couldn't relate to any of the

heroines written by men: Madame Bovary, Anna Karenina and so on. I had not the

slightest understanding of what Madame Bovary was about. I just thought, "Why

couldn't she have gone on having lovers?" I always thought there was something

wrong with me, but it was the writers. Then I got good at writing novels and

felt I had a duty to carry on. The fact that I am still trying to get it right

more than 30 years later amounts to a failure, I suppose. But everything you do

is a failure, in as much as it wasn't what you set out to do.'

It is an unexpected comment, not

least because this is a not a woman burdened by self-doubt. Perhaps it is a part

of her 'truth therapy', perhaps it is just another example of her charming,

frivolous mendacity. After all, she gives the appearance of candour but she

clearly inhabits, as she puts it, 'a world of her own' - a fiction writer's

world.

It is time for the unserious Fay

Weldon to visit her serious mother, who lives in a retirement home nearby. Her

mother doesn't come out of the autobiography in a particularly favourable light,

I point out. Has she been given a copy of it to read yet? The author mouths the

word, 'No.' A ghost of a smile. 'Not yet. I've been rather putting it off."'

May 05, 2002

Review: Memoirs: Audo Da Fay by Fay Weldon

LYNNE TRUSS

AUTO DA FAY by

Fay Weldon (Flamingo £15.99 pp367)

Fay Weldon

learnt to argue at St Andrews about 50 years ago. It is debatable whether this

was a good thing. “We had an agreeable way of conducting dialectic,” she

explains in her artful autobiography. “I say something extreme, you say

something equally extreme in denial . . . and in the end a compromise is

reached. It is like a successful trade-union negotiation: you go in asking for a

third more than you know you will get.” These days, however, as she cheerfully

admits, the system has broken down. “I say my over-the-top things, wait for the

comeback, and there is none. Or else silence, and then uproar.”

It seems

typical of her that, having identified this problem, she adopts a

would-you-believe-it attitude and carries on. Raised in New Zealand in

straitened circumstances by a literary mother, she learnt early not to “rock the

boat” with complaints, a practical outlook that endured. She tells us she has

had a discontinuous life, marked by the surnames she acquired — from Fay

Birkinshaw to Fay Davies, Bateman, Weldon and Fox — but the same person

self-evidently was the sex-mad student; the young woman who coined the (sadly

unused) ad slogan “Vodka Makes You Drunker Quicker”; and now the woman with the

ultra-rational, killer-sweet tones on the Today programme arguing that men have

had a tough time of it lately, and need someone to stick up for them.

What a shame

life is plotless, she sighs. So many loose ends! And then she just gets on with

it, knowing that the rich, fruity haphazardness of her experience will startle

and amaze. This book stops at the point when, in the early 1960s, she became a

writer. Up to then, there has been a pattern of rather brutal childhood

uprootings, then “home” to an unknown England in the freezing winter of 1946-7,

life below stairs, an illegitimate child, and a romantic career so potentially

damaging — yet so gleefully undertaken — that a modern feminist reaches for the

smelling salts. Weldon’s strength was always that she accepted without surprise

what the world provided. She refuses to consider that it might also have been a

weakness.

This is a book

that reminds us of the value of living first, writing later. Pity the earnest MA

creative writing student nibbling his keyboard at East Anglia, whose imagination

could never summon up stuff like this. Those reviled, racy GI brides on the boat

from New Zealand after the war — what a subject! Fay’s days working in the

Foreign Office, where her reports on Polish affairs were marked like school

essays by Churchill himself — “Exc”, “V.G.”! Married to Mr Bateman in the 1950s,

she is urged by her husband to take a job as a nightclub hostess — and instead

of slipping arsenic into his jam roly-poly, she complies! As they say, you

couldn’t make it up. It is all, as ever with Weldon, an exercise in disarming

the reader. Disarming is what she does best, tempering the sometimes sensational

content (ghosts, a few times) with rational-sounding, aphoristic

generalisations. “I have never known a confession of infidelity work anything

but harm” — that’s the sort of thing. “Making tasteful, natural craft objects in

the home is never an effective way of making money.” “Wombs are now seen as

optional extras to the female, not the root of their being, as once they were.”

“I generalise,

of course,” she says. “But when did I ever not?” And you have to admire the

force of personality. This is the woman who coined “Go to work on an egg” and

“Unzip a banana!”, don’t forget — you can’t expect her to hang about questioning

her right to have an opinion. Dismissive as ever about the benefits of therapy,

she is revealed here as therapy’s living rebuttal. “But what do you want to

understand yourself for, Martha?” she quotes Thurber, approvingly. Thus this

book is not a therapeutic exercise in pursuit of “closure”, and in the end, can

be commended for this above all. Weldon remembers her training: she sees one

side, and however daft, the other; then she comes to an overview. Only Weldon,

one feels, could explain how today male doctors have fewer opportunities to

molest female patients, and then add, “Mind you, these days it is much harder to

get an appointment. As ever, something’s lost and something’s gained.”

Life and loves of a mischievous devil

7-5-2002

Auto Da

Fey

Fay Weldon (Flamingo, £15.99)

Reviewed by Jane Shilling

One of the reasons that I

have never much cared for Fay Weldon's novels is that they seem to have a

certain bullying quality about them. Not a hairpulling, wrist-twisting sort of

bullying, but a kind of insistent emotional tyranny, like the girl in the

playground who decides that she is going to be your friend, whatever views to

the contrary you may entertain.

Weldon's novelistic persona

is perpetually there, standing a bit too close and breathing all over you,

nudging you in the ribs in case you've missed some nuance of the action, keeping

up a constant patter of coy little quasi-aphorisms, each of which has the tired

tinkliness of a newspaper horoscope or fortune-cookie motto, as though no one

ever quite thought of it for the first time.

One advances a trifle warily

on the autobiography of a writer whose immensely popular and successful novels

one knows one dislikes. No one - or very few people - really enjoys not liking

things. It is human nature to want to praise, to admire, to be entertained. The

title of Weldon's memoir, Auto Da Fay, is not engaging. It sounds as though it

were thought up by a jaded sub-editor late on production night after an

incautious trip to the Dog and Duck. And anyway, the pun doesn't work, does it?

No immolation on grounds of faith here, surely?

The jacket design, on the

other hand, is strangely disarming. It shows a painting of a small girl,

evidently Weldon, whose looks have changed very little - facelift or no facelift

- in the intervening decades, dressed in a tidy red gingham frock and harsh

green cardie, flanked by a brace of rather horrible dollies, gazing with that

familiar, knowing little smile, which is, you notice, unnervingly at odds with

the expression in her vast, blank, blue eyes that could be dread, or a terrible

resignation, or simply acute boredom.

In the book, Fay (who turns

out not really to be called Fay at all, but Franklin, with a considerable string

of different surnames on top: she has theories about changing your name and the

subsequent effects on the personality of doing so) says that the child's

expression in the picture is probably boredom - unlike her sister, Jane, who was

also in the painting, she had trouble sitting still. But hindsight could equally

well read those darker emotions into the child's harebell stare. Truth, as

Weldon remarks here, on more than one occasion, is much stranger than fiction.

And, a reader's voice might add, ever so much more interesting.

The story is one of genteel

horror, resourcefully borne. On both her parents' sides of the family there are

patterns of emotional disruption. Weldon is interested in patterns, perhaps

because so much of her own early life seems so frighteningly unpredictable - one

or another parent absent; continual changes of home and school; a wrenching move

from the comparative security of New Zealand to grey, postwar Britain;

abandonment and madness, unexpected pregnancy and forgotten birthdays - all

accompanied by the kind of poverty that is the more grinding for being

respectable.

At one point - when she

marries a Mr Bateman in order to provide a home for her fatherless-baby - the

narrative sidesteps from first person into third, remarking laconically that

"Fay Bateman is more than the current 'I' can bear". The story stops quite

suddenly, too, with the birth of her second child. "What I do from now on ... is

write, and let living take a minor role," she concludes, a trifle mischievously,

since it is, after all, still only 1963.

The horrors are recounted

with a sprightliness that seems, when one knows that a real person endured them,

more gallant than annoying. The aphoristic tendency flourishes, too: " People

trusted far more to luck then than they do today." "Today's teenagers ... have

to take their ecstasy in pill form; we created our own." And so on.

At such moments, Weldon can

sound like a version of Lynda Lee-Potter on whom some kind fairy has bestowed an

enhanced gift for narrative. But when one considers the nature of that

narrative, the brutal unsteadiness of the voyage that she has navigated with the

help of these little verbal aids to buoyancy, suddenly, the garish colours and

irritating tendency of her literary style to bob about seem not merely

explicable, but endearing and - with a sudden shift of focus - admirable.

The ones that got away

by Rachel Cooke

3-5-2002

| |

Fay Weldon looks for all the world

like a contented New Jersey housewife - the kind who eats too many Oreo

cookies and cruises around town in a vast, four-wheel-drive people carrier.

I am sitting in the cluttered kitchen of her Hampstead home trying to avoid

admitting to her third husband, a former book-seller called Nick Fox, that,

yes, it was me who gave her last novel such a stinking review, when she

arrives. |

|

|

|

Round and blonde and smiley, she is wearing a navy

T-shirt, matching baggy trousers and a pair of white Nike trainers. Never in a

million years would the casual observer surmise that this suburban pixie has 35

books to her name - or that, on Sunday night, she will be the subject of a

glowing South Bank Show documentary.

But appearances are deceptive

- as Fay knows very well. After all, before she decided to write her

autobiography, who would have guessed that, in her youth, she flirted with

prostitution (she was once given a pair of nylons by a creepy-sounding market

stall-holder in exchange for sex) and worked, rather successfully, as it

happens, as a hostess in a Soho clip joint? Not me, that's for sure.

"You are what you are, you

did what you did," she says later, when I ask her why, at the age of 70, she

finally chose to reveal these risque episodes to an agog public. "There's no

point in hiding it. In that sense, I'm totally unrespectable. I only regret the

men I didn't go to bed with."

The memoirs, entitled Auto Da

Fay, tell the story of Weldon's haphazard childhood in New Zealand and postwar

London, where she lived with her novelist mother and elder sister, Jane. But

things start to get really interesting later on, after she leaves St Andrew's

University.

Fay gets pregnant by the

doorman of the Mandrake Club and decides to keep the baby. She has a son,

Nicolas, but life, she discovers, is tough in a world where respectability is

all - so when Ronald Bateman, headmaster and owner of a property in Acton, asks

her to be his wife, she agrees. The marriage, however, is sexless - Ronald, 25

years her senior, is more interested in life at his Masonic lodge than in her.

At this point, she starts "entertaining" strangers.

Bateman encourages this, even

offering her to his friends. In fact, he longs to hear details of her naughty

encounters. Finally, though, she can stand life in Acton no more - it is boredom

rather than shame that sees to this - and she hops off once again, eventually

landing herself a job in advertising.

Not long afterwards, at a

party in Belsize Park, she meets Ron Weldon, the man who was to be the father of

her other three sons and her husband for 30 years (this union was finally

shattered by an astrological therapist who told Ron that he and his wife had

incompatible star signs; Weldon died in 1994). Here, the book ends.

Ronald Bateman sounds an odd

creature: sometimes kind, sometimes cruel (luckily, he is dead, too, so we can

say what we like about him). "Yes, he was all these things," says Weldon, giving

me one of her wide-eyed and innocent smiles. "He wasn't a bad man. He was just

confused. He kept marrying unmarried mothers with sons." How much poetic licence

did she use in describing life in Acton? Did she, I wonder, have her eye firmly

on sales as she scribbled away?

"I left a lot

out," she says, tartly. "And certain parts you put in the third person otherwise

you feel rather horrified by them." But Weldon famously thinks you can have too

much truth. Didn't she despise herself for spilling her guts?

"My publisher asked me to

write it and I got on with it. Only afterwards was I cringing in a corner,

waiting for the headlines to pass." Has Nicolas read it? "My children are not

allowed to read anything I write. If they do, they're not allowed to talk about

it. The extracts were very lurid. I told Nicolas not to read them. So,

naturally, he went out and bought the paper. He didn't know it all already, but

he thought it was very nice.

"The past is so hidden to

people now. The 1950s are like Edwardian times, they feel so far away. It was

very tough for women. People don't understand what life was like. Now, it's so

easy to have a baby, you just lie there, or stand in an alley. You don't have to

work, there are benefits. I'm just surprised that the teenage birthrate is as

low as it is."

At this point, the door to

the living room opens and in comes Nick (he is 15 years younger than Fay and a

bit manic). To my horror, in his hand is a copy of the review I wrote for the

New Statesman of his wife's most recent novel, The Bulgari Connection (so-called

because it was sponsored by the Italian jeweller). He has an extremely

protective look on his face.

"Now listen to this!" he

says, voice booming indignantly. "You (he means me) worry that she (he means

Fay) says that women menstruate at the full moon and that oral sex is good for

the complexion." Oh dear. This is true. I can hardly deny it, given that it's

there in black and white in front of him. "What else? Yes, you say 'distinctly

feeble ... what this story lacks is SPARKLE!'"

OVER at the other side of the

table, like a kindly goblin, Fay is giggling merrily. Perhaps the cheque she

received from Bulgari was sufficiently big for her not to mind my petty

criticisms. "She's very hard, isn't she?" she says to Nick. "She's very

difficult. She probably didn't like it because it didn't have any sex in it.

Look, you've embarrassed the poor girl now."

Fox leaves the room, his work

done. I look at his wife. She is not at all flustered (unlike me). "It's all so

subjective," she says. Later, she tells me that she loves being married, and

that she did it again for a third time so as not to let Nick get away. "The good

marriages are the irrational ones," she says. "The coming together of opposites.

But the therapists disapprove of those. The ones they like are the dull ones,

where people have shared interests and talk about their incomes. You're not

meant to be consumed by jealousy or rage or hysteria. The expression of those

emotions is forbidden. But we need more weeping and wailing and shrieking." She

has a hunch that the rot set in emotion-wise after women started working in

offices. "There, they just can't shriek at their fellow workers and beat them

about the head."

It's hard not to enjoy her

delicious habit of saying the very opposite of what you're expecting. In her

day, she says, bulimia was a "skill not a disorder". Neither can she understand

why modern girls make such a fuss about fitting in babies. "What do these women

mean when they talk about their careers? It's all in their heads. On the whole,

people have jobs, not careers."

When her 27-year-old son Tom

was sent to a Dutch prison for three years for possession of drugs, "it did him

a power of good". He learned to paint and is leading a normal life again, she

explains. Most bizarrely, she thinks that women who reach 40 without having

married or bred spent "too much time combing their hair and complaining about

their period pains".

Luckily, breeding was never a

problem for her and she now has five grandchildren. But for all that she

pretends to have no ambition - "I didn't set out to do all this" - she has no

intention of settling down into a quiet retirement just yet. She is already

working on a new novel and volume two of the memoirs is bound to contain more

bombshells. "When I turned 70, I thought it was time to behave with a certain

gravitas," she says. "But that remains hard. I'd rather be 20. Who wouldn't?"

Auto da Fay by

Fay Weldon

How did a maid

of all work reach the top table? Susan Jeffreys samples a savoury life

18 May 2002

In the

world of cooks and scullery maids, death often came calling in the middle of a

banquet. A cook's life was hard. The hours were unending and the stress

unbearable. Rich food and frequent nips at the sherry bottle meant these women

often fell where they cooked. The meal had to go on, so the maid simply took

over the dead woman's place, while the other servants dragged away the body. It

was how a girl got promotion and was baldly referred to as "stepping over the

cook". Fay Weldon records the practice, and attributes her own rise in the world

of advertising to a 20th-century equivalent, in this strange, deceptively

formless but actually very structured autobiography of her early life.

Fate

and will, nature and nurture are underlying themes in this book, and in her

life. Scheduled to be born into a tolerably settled doctor's family in New

Zealand, Fay was actually, thanks to an earthquake, born in London into a family

fractured by much more than an earthquake. Blown backwards and forwards between

England and New Zealand, scrabbling around to get an education and make a

career, Fay Weldon got on with what was under her nose. It was a family

tradition, handed down through the female line. Her mother, born to an eccentric

intellectual family in Hampstead, worked as an artist, a writer, a guard on the

London Underground, a home help and whatever else came her way.

Exasperated into adultery by her husband's philanderings, Fay's mother brought

up her two daughters, along with her own idiosyncratic mother, shifting them all

back to England for the last time on an unexpected legacy. If that money hadn't

arrived Fay and sister Jane might have stayed in New Zealand and been happy

housewives with perms. The book is littered with paths not chosen, but what

appear to be random, whimsical decisions seem to have a theme and structure.

This is

so much more, though, than one woman's journey over difficult, seismic terrain.

Fay Weldon is not so wrapped up in telling the extraordinary facts of her life

not to notice the scenery around her. Her account of arriving among the blasted

buildings of post-war Britain, of sexual politics before and after the pill,

about suburban behaviour and social mores, are sharp and particular. She

remembers, as few others would bother, to record how when a husband came in the

front door any visiting female neighbour would sidle out the back. She records

all those lost tribes: sleazy doctors who got by on work for insurance companies

and were prone to groping the daughters of doctors, the first wave of

advertisers working for commercial television, the last wave of poor tenants

hanging on by a legal thread to lodgings in up-and-coming areas.

An

unmarried mother in the Fifties, Fay Weldon got on with being a career woman.

Stuck at home with a pregnancy that seemed unending, she got out the pen and

paper and became a writer. Husbands, lovers, a truly bizarre cast of relatives,

and a few ghosts, have pushed her life this way and that. But she was always

determined and resourceful, and she has always had her tremendous talent for

writing. Weldon may have simply stepped over the cook and done "what was under

her nose", but she had to be willing to do it.

Fay Weldon:

You ask the questions

Such as: so,

do you like men as much as you like women? And what are your views on the

cloning of human embryos?)

09 May 2002

| |

Fay

Weldon was born Franklin Birkinshaw in Worcestershire in 1931. She was

brought up in New Zealand and London. She went to St Andrews University and

worked in advertising for several years, inventing the slogan: "Go to work

on an egg." Her 24 novels include Big Women and The Life and Loves

of a She-Devil, which was made into a TV series and a Hollywood film.

She has four sons and five grandchildren and lives in Hampstead with her

third husband, Nick Fox. She has just written her autobiography, Auto da

Fay.

What have you discovered about yourself by writing an autobiography?

Cynthia Pakes,

Milton Keynes

Not

much. Perhaps a little more about what applies to everyone: how we tend to

repeat our parent's mistakes, how we don't spring ready-made into the world,

how all our stories start long before birth. How the decades form us, and

how the society around us dictates our morality, our opinions, and the form

our self-esteem (or lack of it) dictates. |

|

|

|

You talk a lot of sense about

men and women. Is this because you like the former as much as the latter?

Jeremy Q Sleath,

Leamington Spa

Thank you. To dislike either

men or women would be to dislike half the human race, and a fairly pointless

exercise. I'd rather go the cinema with a girlfriend; I'd rather go to a party

with a man.

You're lucky enough to have

four sons, but did you ever yearn for a daughter?

Debbie Pinks, by e-mail

Of course I yearned for a

daughter, though I was exceedingly grateful for my four sons. In the past, if