Pages of

this site about Camilla Paglia,

here

and

here

Previous

page

Break, Blow, Burn,

by Camille Paglia

| |

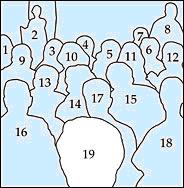

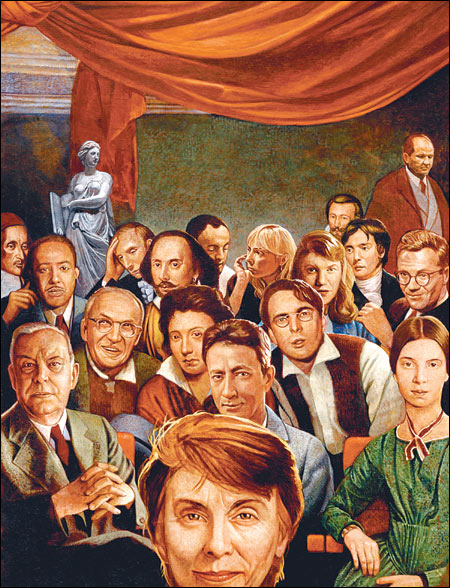

1. George Herbert

2. Calliope

3. William Wordsworth

4. Frank O'Hara

5. Joni Mitchell

6. Samuel Taylor Coleridge

7. John Donne

8. Theodore Roethke

9. Langston Hughes

10. William Shakespeare

11. Sylvia Plath

12. Robert Lowell

13. William Carlos Williams

14. Percy Bysshe Shelley

15. William Butle Yeats

16. Wallace Stevens

17. Jean Toomer

18. Emily Dickinson

19. Camille Paglia |

Picture by

Ed Lam |

|

|

Warrior for the

word

Camille Paglia slams bloggers and trendy academics for degrading language -- and

calls for a passionate revival of the great artistic tradition of the West.

By Kerry

Lauerman

April 7, 2005

| Camille Paglia's

first major

work since "Sexual Personae," the 1990 bestseller that cracked a bullwhip over

the heads of dogmatic feminists and a p.c. academe and turned its author into

our favorite provocateur, appears, at first glance, to be a surprisingly demure

offering. "Break, Blow, Burn: Camille Paglia Reads 43 of the World's Best

Poems," in fact, was almost titled something as modest as "Readings"; she says

she didn't want anything to overshadow the poems (from Shakespeare to Plath)

that she chose to honor.

But, true to Paglia's form,

there's an incendiary call to arms inside "Break, Blow, Burn" (a phrase taken

from John Donne's "Holy Sonnet XIV"). Her celebration of these poems -- each

reprinted and electrically interpreted -- is paired with a blistering critique

of what she sees as the cultural and academic forces that have conspired to

undermine our enjoyment of poetry, lessening its importance in the process. She

demands reform and believes it will be up to graduate students and poets

themselves to lead the way. "In an era ruled by materialism and unstable

geopolitics, art must be restored to the center of public education," she

writes.

We caught up with Paglia, a

founding Salon contributor, as she commenced her book tour. Our talk covered a

range of topics, from lazy college elites, poets who didn't make her cut (sorry,

Ginsberg, Bishop, Eliot, Ashbery) to raising a son while refusing to act like

Rosie O'Donnell.

This is your first big book

since "Sexual Personae."

Well, there was my 1998 book on

Alfred Hitchcock's film "The Birds." And I did always write original material

within my two essay collections. But writing requires time, and I do give it

time. This one took an exorbitant amount of time, to the extent that, as you

know, I had to resign as a columnist from Salon to work on "Break, Blow, Burn."

The problem really wasn't the time required to write the column. It was the

amount of filtering I had to do of other people's columns to keep the Salon

column fresh.

And you had to absorb a lot

of it. I mean, a week like this -- Terri Schiavo, the pope -- would have been

tough.

Yes, exactly. And of course I

was always in competition with the other big-name columnists -- who would

shamelessly rob from me. You know, it's like I would be in Salon on Thursday,

and something from it would show up in Maureen Dowd's weekend column, and so on.

But I had to make sure that when people went to it that it didn't just seem to

be a rehash of someone else's column. And that's the problem now, of course. I'm

a professor of media studies as well as humanities, and I'm an evangelist of

popular culture, but when there's only media, then there's going to be a slow

debasement of language, and that's what I think we're fighting.

The blogs, for example, are

becoming so self-referential. If people want to be better writers, they can't

just read the blogs! You've got to look at something that's outside this rushing

world of evanescent words. Nowhere in blog pages does anyone pay attention to

the individual word -- things are moving too fast. Someone like Emily Dickinson

was working with the dictionary and looking at the etymology of the word, so

that you have all this tremendous stuff going on within a single word!

My publisher forwarded this

amusing thing from Gawker.com

the other day -- it was reporting on the review of my book in the New York Times

Book Review. It really was quite revealing. It was written by a young woman who

said she was a recent graduate of Yale. And she said that as she was reading

that long, three-page review by Clive James, her eyes glazed over because it was

about poetry. And I thought, Oh, my God -- if this isn't a testament to what's

gone wrong in the Ivy League!

Here you have a smart young

aspiring writer who's saying that somehow she has not been educated in a way

that allows her to appreciate poetry. She's never been shown that you can become

a better prose writer through reading poetry. I certainly derived my skills as a

prose writer from my scrutiny of poetry and of the individual word. But schools

don't do things like that anymore -- tracking words down to their roots. It's

hopelessly old-fashioned. But that's the whole basis of the power of English

as a literary language.

I say in my introduction that

I'm in love with English -- it's a phenomenal instrument. People who like my

work recognize that I have many styles as a writer -- the high academic style,

the newspaper style, the conversational style. My sense of English comes from

the fact that I was born into an Italian immigrant family which was still

discovering America.

I read where you said you

tried to make yourself as invisible as possible for this book. To most of your

readers, the idea of rendering yourself invisible sounds like quite a feat.

I felt it was important that I

submerge myself because in the four-year period from "Sexual Personae" to "Vamps

& Tramps" in the early '90s I had as much publicity as any person could ever

want. You have to remember, my first book wasn't published until I was 43, and

that book had been rejected by seven publishers and five agents. I came on the

scene without any publicity. But when "Sexual Personae" started to get

publicity, which was almost a year later after it was published, it started to

get viciously attacked. And I counterattacked!

And so there was a period there

-- when I had three bestselling paperback books from Vintage in a row -- that

represented a whole uprising by a very repressed wing of feminism. When my work

was criticized, people went: "Oh, she's antifeminist! She's a neocon." For

heaven's sakes -- I had just voted for Jesse Jackson in the 1988 primary! An

insurgency was going on -- a major conflict with smug and self-satisfied and

exploitative feminist leaders. We were just coming out of the era ruled by

Andrea Dworkin and Catharine MacKinnon, and so I was in battle for years. But

that was it -- after 1994, I went back to my usual private ways. People say,

"She's everywhere!" But I'm not -- it just seems that way because of the Web and

the many documentaries I've been interviewed for.

When you were doing this

book, it's clear you felt you needed to ratchet back that persona.

Yes, because it's irrelevant to

this book. The people who were really reading me seriously would recognize the

real me -- I'm a classroom teacher, and I've never changed my lifestyle. People

nagged me: "Oh, you should quit that job." Are you kidding? This is my vocation!

And I never let media into my classroom, ever. And because I never let any

reporters into my classes (and they were demanding it), that professional life

has remained invisible. Some people think I must be some sort of a

flibbertigibbet, running around the world in front of cameras. But if film crews

want to interview me, they must come to Philadelphia and meet me after my

classes are over for the day. That's my life, and it will continue to be my

life.

Though you have had one major

personal development in your life while writing this book -- I've heard you've

become a mother of a young boy. There's advice of your own that I wonder if

you've heeded: "Every man must define his identity against his mother. If he

does not, he just falls back into her and is swallowed up."

My partner of 12 years, Alison

Maddex, gave birth to a baby boy in November 2002 -- Lucien Harry Maddex. I am

Lucien's adoptive parent -- but certainly NOT his mother! Alison is Lucien's one

and only mother. That "Heather Has Two Mommies" business gives me the creeps! --

and it can only confuse a kid.

I'm completely against that two

fathers, two mothers stuff. I think it's gay activism gone horribly awry --

people making political points without regard for a child's realistic social and

developmental needs.

I kept Lucien's birth completely

out of the public eye because I absolutely detest the circus that Rosie

O'Donnell made of her children. Kids should not be subjected to the glare of the

spotlight. However, now that I'm back in public after the five years of writing

this book, it's perfectly legitimate information.

Going back to "Sexual

Personae" for a minute, and that battle with the feminist establishment. What's

happening with that now, would you say?

It's over. It's completely over.

I won that war! -- or rather, the wing of feminism that I led into the light won

the war. Madonna made it possible. In New York magazine's cover story on me in

1991, it was reported that a Yale faculty member had marched with her graduate

student in New Haven to return "Sexual Personae" because it was "ideologically

unacceptable." A Yale faculty member would return a 700-page Yale Press book by

a woman author on the basis of its not passing some p.c. litmus test -- that

shows you what was going on!

But things have changed -- at

least in the media. The media has moved on, the media has realized that the

pro-sex side has won, and it has seen all the anti-porn maniacs as what they are

-- fanatical Puritans. When it did a profile on me in 1992, "60 Minutes" sent a

woman producer and a camera to the 92nd Street Y when Gloria Steinem was

appearing on a panel. The producer stood up at the end and asked a question

about me. And they caught Gloria Steinem saying something like, "We don't give a

damn what she thinks!" -- at which the audience loudly applauded. They

caught her and her entire Manhattan elite in action. But then Steinem learned,

once she'd been burned, so that a year later she was saying things about me

like, "She has a right to express whatever she feels."

Still, I was systematically

excluded and ostracized. When Vanity Fair did a cultural-icons issue a little

later, they asked to photograph Betty Friedan, Gloria Steinem and me together --

like the different generations. But Steinem refused to pose with me! So Vanity

Fair had an inspired solution -- it simply commissioned a full-page caricature.

What great revenge -- there were the three of us, Betty Friedan, Gloria Steinem

and me, posing amicably together in cartoon form!

The point is, this hostility to

dissent had been going on for decades in feminism. If they were doing that

repressive stuff to me with a bestselling book, what were they doing to

ordinary women just trying to open their mouths? So it's great that my side has

won so resoundingly. However, the universities are still in the hands of the

feminist ideologues. Nothing has changed at the major universities, nothing. The

same professors are there, but they're really mad now because they know they've

lost! So over the last decade, they've spent a lot of time trying to be me!

They made contracts with trade

presses. They wrote Op-Ed pieces. Before me, only poli-sci or history professors

would write Op-Ed pieces. You just didn't do that if you were in humanities. In

the early '90s, some Harvard woman snob actually said to a reporter about me:

"Oh, we don't consider anyone serious who writes articles for the newspaper."

That's where things were back then. They all tried to write books directed

toward a general audience, and none really succeeded until Stephen Greenblatt's

book on Shakespeare -- which as

far as I'm concerned is ultimately a product of my pressure on the profession in

the early '90s, when I called for literary critics to address the general

audience.

As someone who teaches

Shakespeare, however, I don't think it's a very good book, even though the New

Yorker and the New York Times laid down flat in front of it. Greenblatt's

Shakespeare isn't one I recognize from my own study of the plays, and the

connections posited between the life and the art aren't particularly

sophisticated. The TLS [Times Literary Supplement] reviewer wrote that

Greenblatt is "innocent of English history," which of course is just a

devastating thing to say about the leader of new historicism whose specialty is

Renaissance England and who is head of the Norton Shakespeare editions. But too

many books coming out of the Ivy League tend toward the trendy and shallow --

even though the New York media eats them up.

They do get great press. Why?

It's media sycophancy toward the

brand-name schools. Because a lot of reporters in the mainstream media went to

those schools and want their children to go to those schools, they don't want to

disrupt their brand-name value. The alternative press has been completely,

cowardly negligent, including the Nation. The leftist press has been out to

lunch on this for 25 years -- it's outrageous that this matter hasn't been

vigorously pursued. Because these academics mouth leftist sentiments -- even

though their lifestyles are ones of ostentatious materialism -- the alternative

press has been afraid to appear to take the side of the conservatives who have

justifiably been berating the politicization of the campus since the '80s.

Come on, let's look at reality.

What important, essential works have come out of American humanities departments

in the last 30 or 40 years? The important book just isn't there. Where is the

great American scholar that poststructuralism has produced? When Harold Bloom

goes, he's the last of the line. These people aren't great scholars -- they have

no deep erudition. They just do gimmicky manipulations of other people's

research. The people at the top with the power positions and the huge salaries

are flashes in the pan -- their work isn't going to last.

Like who, precisely? Henry

Louis Gates is frequently mentioned as among the new public intellectual...

Gates is a pivotal figure, a

very shrewd handler of people. He knew how to work college administrations to

guilt-trip them for their exclusion of African-American studies and thereby to

win a huge investment of money for the expansion of faculty and facilities. He

put African-American programs on the map. But as a group they still do not have

a high reputation because so many of them are rife with ideology. Beyond that,

the problem is there are too few African-American scholars to go around --

everyone wants them. There are simply not enough who have entered the

profession. Thus many schools have had to reach further and further down and

hire people who are really marginal in scholarly terms.

Look at the

Ward Churchill case, this guy

who was the chairman of the Ethnic Studies Department at the University of

Colorado at Boulder and who didn't even have a Ph.D. He had absolutely no

scholarly training in anthropology or in anything in ethnic studies -- his M.A.

was in communications. He had no business being rocketed to a tenured position

literally overnight in the early '90s, when he had just been teaching adjunct

courses as a staffer there. All of a sudden, he was earning $94,000 a year.

There's something deeply corrupt in American academe that was rewarding, in this

case, not the color of your skin but a claimed Indian heritage that Churchill

can't prove -- and that one American Indian group long ago called fraudulent.

The whole American academic

system -- which Europeans can't quite understand -- is shot through with this

p.c. stuff that administrations are promoting. It's a marketing tool. "We are

for affirmative action, we're for diversity, we give a rainbow education." And

so there's been a slow decline in respect for genuine scholarship. Gates'

department hasn't yet produced as much high-level work as it should have, but

I'm confident that it will because it is grooming the next generation of

young scholars. They will presumably fan out into the profession, and then we

will see the true fruits of what Gates achieved.

Cornel West, an early Gates'

recruit at Harvard who has now left, is someone mentioned with you as an

academic interested in engaging in popular culture.

Well, Cornel West is definitely

a major American public intellectual. He and I are certainly parallel phenomena.

We emerged strongly in the '90s. We have a wide range of interests from popular

culture to traditional scholarship and philosophy. We are entertaining presences

on the lecture circuit; we are performers -- on TV as well. I myself have

questions about Cornel West's work.

His rap album?

No, the rap album doesn't bother

me in the slightest -- I like the idea. But I've sometimes noticed what I feel

is too big a gap between the writing of his major books and writing I see him

doing elsewhere. I sometimes wonder how much editing has been done of his best

work -- even before it got to the publisher. I've occasionally seen in articles

by him a kind of hasty, careless, demagogic, nearly ungrammatical use of

language and a pretentious, jumbled jargon that I find peculiar compared to the

lean, finely honed writing of his most acclaimed work.

My work is never edited in that

sense. My excellent editor will make a suggestion or a request here and there,

but there is never wholesale rewriting or reorganization of my prose or

alteration of my voice. What you're getting from me is entirely my work.

Another thing that I object to,

and the media seems to really ignore, is how many books by prominent academics

have been supported by graduate assistants and research assistants, often paid

for by the university itself. They're the ones doing all the book-running:

checking quotes, accumulating examples, assembling the footnotes and

bibliography.

As a scholar, I can see it in

people's work from major universities. I can tell who are the professors who

actually did the reading and gathered the quotes, as opposed to people who are

so busy running this or that and exercising academic power that they have to

have examples and evidence supplied to them. And what gets me is when a reviewer

says in awe, "This is a very erudite person -- there are so many pages of

footnotes!" I want to laugh! Well, pages and pages of footnotes in the back of a

general interest humanities book usually indicates weakness. You don't need all

that if your scholarship is solid. And the idea that the trendy professors of

the elite schools have actually read all those books is usually false.

Not only haven't they read them, they haven't even gone to the library to get

them.

I have no research or clerical

assistance whatever. I teach at a small college where I must do every single

thing myself. But that is what, I believe, that sympathetic readers are sensing:

quality control.

West, of course, left after

an infamous blowup with [Harvard University president Lawrence] Summers. What

have you thought of the controversy up there?

What many observers felt about

the Cornel West incident was that Cornel West was so used to being pampered,

idolized and coddled that to have any aspect of his academic performance

questioned came as a mortal blow. It's pretty obvious that Lawrence Summers has

very few people skills and that he is not suited to be the president of a major

university. You have to bring groups together; you can't be a person who divides

groups from each other. But I am sympathetic to Summers' desire to insert some

reality into the knee-jerk, monolithic, Jurassic Park liberalism that passes for

political thinking at that university. Talk about diversity -- there's hardly a

conservative or dissident voice at that place. It's bad for the faculty, it's

bad for the students, it makes a travesty of Harvard's claims of education --

which students are bankrupting their families to pay for.

I think that affirmative action

in the way it has been applied does need to be questioned, but not in

this ham-handed way. The issue that Summers is broaching in the most recent

incident, whether there are genetic sex differences, is an enormously important

one for academe to address. But for 30 years, the social-constructionist dogma

has become entrenched in humanities departments from coast to coast. That's why,

when "Sexual Personae" came on the scene, people went ballistic. They weren't

used to hearing anything about nature. And they were saying, "Oh, she's an

essentialist. She's using the no-no word 'nature.'" But I said that sex is the

"intricate intersection of nature and culture," so it's a combination of the

two.

But you have people who are

getting enormous salaries for being gender-studies experts who have never

studied biology or endocrinology, who know nothing about hormones. They're

ignoramuses. Where the hell are they getting off saying that we're born blank

slates and become male or female only through society's pressures -- what is

this crap that they're teaching? But it's absolutely routine.

To open this debate is crucial,

since there are very few dissident voices discussing this issue in the

humanities. But Summers seems to be a dope. I applaud him for raising the

subject -- the question of biology and its relation to gender. But I have to

condemn him for his unscholarly approach to this matter and the sloppy way he

handled it.

I wanted to know if there was

a particular poet you were really excited to put in this anthology, who you felt

never got the right amount of critical attention. Throughout the book, you

mention how poststructuralist theory has managed to diminish essential poetry.

Well, yes, the Roethke poems. I

can't remember the last time I heard his name mentioned anywhere. "Cuttings" and

"Root Cellar" are about dirt! They're about the body and the body's

responses. That's what has been totally excluded from poststructuralism, because

poststructuralism sees the body as a passive victim to the forces of power

"inscribing" their agenda on us. Poststructuralism is stupidly oblivious to the

relationship between the body and nature -- our bodies are subsets of nature,

not society. It should be rather obvious, but no. The body-centered approach,

the speech-centered approach, to poetry was from the '60s, my era. It was partly

coming from the Beats. For some reason it has been dissipated. I thought it

would be a revolution in American culture.

The primary reason was drugs;

the people most impacted by this radical view of life were destroyed by drugs.

The solid academic poets just churned along, drinking alcohol, but everyone else

was brain-dead. So it thrilled me to see Roethke depicted in the wonderful

illustration accompanying my review in New York Times Book Review. Then when

Matt Drudge put the picture up on the Drudge Report, I thought, "Hooray! This is

Roethke's first appearance on a major news Web site!" My college teacher Milton

Kessler was a graduate student of Roethke's at the University of Washington. I

feel a particular thrill about that, because I believe in lineage, you see. This

wonderful lineage -- it goes from Roethke to Kessler to me -- and from me to the

young people who will read "Break, Blow, Burn." You never know who's going to be

inspired.

It's like the movie "The Turning

Point" when the old teacher says to the aging ballerina played by Anne Bancroft,

"You are passť. You must be a teacher now. I learned from the great so-and-so in

Russia. I passed it on to you, and now you must pass it on to her!" -- the ditsy

young dancer who has to be waved away from the pastries. I just love that idea

of lineage and transmission from generation to generation -- and those

connections are precisely what I think have been broken in the domination of

French theory in the last 30 years.

Right, because even though

this book might not be as immediately, obviously contentious as "Sexual

Personae," it's a shot across the bow of the academy.

Oh, yes, and I'm also trying to

inspire an insurgency movement of embattled teachers everywhere. I want to say

to the adjuncts who are working so hard, going from school to school, without

benefits: Your love of literature and art and your teaching students who are not

going to be big-shot Manhattan executives but who are just going about their

workaday lives -- you belong to a real American cultural movement, and here's a

manifesto for you. The way you approach things directly and honestly, that too

is a theory! All these people who claim to be so superior to you because they

"do" theory -- they're fakes. And they've destroyed the prestige of humanities

departments.

You are trying to pass this

on to the adjuncts, the grad students. But you've also mentioned that the poets

should do this themselves. How can they do that in a culture where the poetry

that does exist comes out through pop music, hip-hop. How do the poets assert

themselves?

Well, first of all, they better

stop talking just to each other in those small groups of the like-minded. I used

to like John Ashbery, for example, but he got addicted to critical adulation.

Too many people want academic idolization. They want the prizes. I want the

poets and all artists to address the general audience again: Stop addressing the

like-minded true believers, cut out the partisan politics, stop thinking that

the only people you can speak to are those who agree with you already. Writers

and artists need to start addressing those who don't agree with them.

That's certainly what I do. I've

won a very wide audience in that way. I listen to or monitor a huge range of

opinion, including on talk radio, which I love. I want to understand how most

people think! That's why I can communicate with large numbers of people. What's

the secret? The secret is I cannot stand the coterie mentality, whether it's in

downtown Manhattan or in Cambridge, Massachusetts, or in L.A. I cannot stand the

cool in-group -- "We are the special people, we are the best people, everyone

else is just rubes and hayseeds." Get over that! People who claim they're

leftists and who have contempt for ordinary people and how they vote. I voted

for Kerry and Clinton, but I don't look down on people who voted for Bush. I try

to understand it.

The most recent poem in your

book is the last one, Joni Mitchell's "Woodstock." Is there anyone more current

who you look at and say, "There's a poet"?

No.

But hasn't there been a true

revival of the spoken word since then? In rap and hip-hop...

Rap is not transferring well to

the page -- though if I ever write a book on song lyrics, rap would certainly be

in it. To get into this book, the lyrics had to transfer well. I invented this

course at my school for musicians to develop their lyrics. I often would be

disappointed when I would transfer lyrics from my favorite songs onto the page.

My criterion for this book was that there has to be a kind of shapeliness to

what a poem looks like on the page; there has to be a kind of visual that the

reader gets. None of the arts are separate for me: They all feed each other.

Visual arts, literary arts and music -- they're all mixed together for me. I

think we've kind of lost that sense that there's a pleasure at looking at

something on the page. For a poem to survive the cut in my book, it had to be

pleasing every time I returned to it. Every time I went back to it, I had to see

a visual vitality, I had to be drawn into it visually -- not just in terms of

the content.

The controversial thing in the

book is that many of the contemporary choices are completely unknown. I did not

anticipate that when I started doing the book. The most famous poets of our time

were listed in the original proposal for the book given the publisher, but when

I actually gathered the material, I did not find the strong poems I was looking

for.

Is there anyone you're

surprised did not make the cut?

A whole series. Poets I heard

reading in college who I thought would naturally be here -- A.R. Ammons, W.D.

Snodgrass, John Berryman, John Ashbery, James Merrill -- just name after name. I

couldn't get Ginsberg in, unfortunately; what I would have had to do was excerpt

"Howl," and I just didn't think it was going to work. Auden -- I found virtually

nothing that would work, and it astonished me. I didn't find an Auden poem that

I felt I could endorse for the general reader and say, This poem will repay your

constant rereading. Example after example -- Marianne Moore, Gwendolyn Brooks,

Denise Levertov. I was looking for sports poems, animal poems, war poems,

antiwar poems. I was bitterly disappointed.

At the end of the

introduction, you write: "I am uncertain about whether the West's chaotic

personalism can prevail against the totalizing creeds that menace it. Hence it

is critical that we reinforce the spiritual values of Western art, however we

define them." It has a markedly a different note than "Sexual Personae," which

is largely celebratory and optimistic about Western culture.

But no, actually. "Sexual

Personae" is about decadence! -- the beautiful decadence of Western

civilization. There I say I am a decadent, and I celebrate it, but I don't know

how long the West is going to last. If our popular culture is equivalent to

Hellenistic culture during the Roman republic and empire, I have no idea if we

are going to last 50 years or 500 years. But there is no doubt that there is an

end to every civilization, whether it's from some climatological disaster or

invasion or something else. I mean, last December's tsunami showed everyone that

my vision in "Sexual Personae" of nature was right -- that we just huddle here

on the thin, brittle skin of the globe. Civilizations rise and fall. I'm saying

it's time for us to reassess our conceptions of the West. In all its failings,

the West has produced a great art tradition.

So I'm saying to the left: Stop

bad-mouthing your own civilization; get over it, you little twerps. I'm saying

to the religious far right: If we are defending Western civilization, as you

claimed in the incursion into Iraq, then you'd better realize it's much more

than Judeo-Christianity and the Bible. You'd better get real and accept that we

have a Greco-Roman tradition of literature and art that started in 700 BC. And

yes, some of it deals, quite frankly, with sex and the body; you must deal with

it and allow students to deal with it, because that is part of the brilliant

strength of our arts. I'm demanding that conservatives support the arts and that

liberals stop being so snobby about art and quit celebrating art that is simply

cheap sacrilege of other people's beliefs.

Artists have got to get back to

studying art history and doing emotionally engaged art. Get over that tired

postmodern cynical irony and hip posing, which is such an affliction in the

downtown urban elite. We need an artistic and cultural revival. Back to basics!

About the writer

Kerry Lauerman is Salon's New

York editorial director.

April 8-14,

2005

Art demon

Camille Paglia talks (and talks and talks) about her new book on poetry ó and

academic Ďass-lickersí and Ďliberal media elitesí had better respond

intelligently for a change

BY TAMARA WIEDER

ANYONE FAMILIAR with

Camille Pagliaís rapid-fire delivery and

take-no-prisoners polemics knows that she has a lot to say. Fifteen years after

the publication of her provocative first book, Sexual Personae, the

renowned ó and controversial ó scholar and critic continues to speak

passionately on subjects ranging from politics to art, higher education to

liberal media. In her latest book, Break, Blow, Burn (Pantheon), Paglia

tackles the subject of poetry, offering thoughtful commentary on what she

believes to be 43 of the best poems in the Western tradition.

Q:

Tell me first why this book, and why now.

A:

I spent five years on the book. When someoneís very much in the public eye, the

pressures are enormous to churn the books out like sausage, to keep in the

public eye. I felt, personally, that I had had as much publicity as anyone could

ever want. The last five years Iíve been doing this book, I have been really,

really reclusive and been very low-profile.

What Iím trying to do, partly,

is to set an example for writers and aspiring artists and even performing

artists ó anyone who works in some branch of arts and letters ó to take the time

to really make sure that the product is quality and has staying power. Iíve

tried to link up my work to some of the best history of commentary on art and

literature. So I spent two years actually doing the writing. I spent two years

just on the prose, to try to make it as accessible as possible to the general

reader, and to young people, without losing the people who are already familiar

with the poem.

Iím a great evangelist of

popular culture, Iíve always been. And it cost me something. When I was at Yale

Graduate School in í68 to í72, nobody took that seriously. They thought I was

really not very solid, the fact that I was interested in movies and TV and

astrology and all kinds of things. So I really paid a price for it in my career,

that is, almost always being thought of as not serious. But I maintained that

there is a bridge between mass media and the fine arts, or there should be a

bridge. Eventually cultural studies came on the scene that made that idea

acceptable, but I despise what calls [itself] cultural studies. Itís a wonderful

phrase, but I despise what theyíve done with it. All it is is informed by

British Marxism and the very censorious Frankfurt School, Adorno and so on. I

mean, who cares about listening to these foreigners, especially

male foreigners, about our popular culture? This is one of the great acts

of genius of American culture: we created Hollywood and the entertainment

industry; weíve swept the world with it, right? But hereís my dilemma: in the

í90s, I started to observe its decline, with horror. I think I started noticing

it after 1992; I felt that Sharon Stone in Basic Instinct was the last

truly mythological work coming out of Hollywood, and that after that, itís been

just this juvenility and special effects and dizzying editing and lack of

development of script and stupid casting. Everythingís image, image, image, so

that the pressure on young actors is terrible. I teach at an art school

[University of the Arts, in Philadelphia], and itís terrible, that young

people have to present an image when theyíre just learning their chops.

Itís really sick.

Iím a great supporter of the

Web. I feel that young people are rightly tuned into the Web. I think itís the

absolute future. Itís just going to transform everything in culture. So I

totally support it. But the end result is that step by step, the use of language

is becoming very tinny. People are not taking time to write; they just blog or

e-mail. You just write. You donít consider how youíre writing something, as you

would in the old days when you wrote a letter to somebody that you knew they

might save. So thereís a slow degeneration in the quality of language in

America. I was determined to force these issues back into the public eye, and I

wanted to use my particular celebrity to push this, and to say, "There are

things that last." So the things that are in this book are things that have

sustained me for all these decades.

Iíve tried to aim the book to

both ends of the political spectrum, so I have religious poems ó George Herbert

and John Donne ó and I have poems of radical social protest, like William Blake

and so on. Iím trying to bring the audience together. Liberals have allowed

themselves, in America, to become too snobby, sanctimonious, and pretentiously

elite. I mean, liberals have got to wake up and stop hunkering in these

sophisticated metropolitan ghettos that theyíre in, and come to the realization

that they must address the general audience in the way that the great

Hollywood studio system did. Masterpieces came out of Hollywood. My God,

theyíre things that last, like Gone With the Wind ó Iím talking not

necessarily about the racial things in it, which are very sensitive, but Iím

talking about the performances and the music and the costumes. Thereís an

emotional link with the general audience in that. So what Iím saying is, get out

of the ghetto and decide, what do you favor? Do you just want to go around with

a little badge saying, "Iím sophisticated, and those people are such rubes,

those far-right people"? You want to do that? Okay, destroy the American

arts, because thatís what youíre doing.

Iím a liberal Democrat. I voted

for Kerry, I voted for Clinton twice, I voted for Jesse Jackson in the

1988 primary. Thereís a really depressing disconnect with how regular people

really think, and how they live their lives. And I tried to keep up with

it by listening to talk radio, even very conservative talk radio. Well, this

failure of the liberal elite to take account of this incredible populist medium

of talk radio meant a disaster for Kerry last year. Because I

heard on talk radio in April about the Swift vet stuff. And it took that

Boston-based campaign until August to try to deal with it. It was a

runaway massacre that went on for months. I heard it for months; I

thought, what is the matter with these people? The elite is totally out

of touch. They want to scorn, "Oh, the demagogues of talk radio." Oh

really, demagogues? Come on. There are demagogues on both sides; thatís

politics. If youíre going to be president, you have to learn how to fight the

fight, and Kerry didnít know. He didnít know how to respond, to talk to the

people in a way that made them trust him. And Bush, oh my God, all of a sudden

his campaign made him go out and take off his jacket and [roll up] his sleeves,

and he was out there roaring with the populist energy. I thought, how did

this happen?

The liberal elite of the two

coasts, they donít understand what people are thinking. I want artists to start

trying to get out of their mental cubicles. For great art, and important

artistic statement, you should be aiming to communicate with the vast audience.

I mean, I was looking for anti-war poems, and I found practically nothing

that was a strong poem. Why are they so weak? Because theyíre snide, and

theyíre preaching to the choir. What we need are strong anti-war poems

that are written to the people who donít agree with you. That try to

awaken the imagination of the people, about military incursions or the

horror of war and all those things. We need the artist to be addressing

everyone.

Iím also berating the far right,

because I say, okay, we went into Iraq to save Western civilization?

Well, excuse me, itís more than the Judeo-Christian tradition and the

Bible. Itís also the Greco-Roman tradition of the arts that goes all the way

back in poetry and the visual arts to 700 BC. Youíre always talking about

getting back to basics and getting back to the canon and all that stuff. Well,

you better put your money where your mouth is, and you better realize that there

may be things in the history of Western art that donít quite fit with the

Judeo-Christian scheme of things. You are really going to have to bite the

bullet if you want a cultured society, as you claim; you better do some real

studying of art.

A (cont.):

Young people are not getting any substance. So now Iíve written a book that I

wouldíve wanted to have when I was a high-school student or a college student,

and Iíve tried to reach the general reader, who didnít go to college, and tried

to draw them into aesthetic response ó because aesthetic response, of course, is

a no-no. I mean, in an age of post-structuralism and postmodernism, that was

driven completely out. Thatís why Iím on the edge of everything. Iím totally

persona non grata. Iím never invited to speak, and when I am invited to speak,

interestingly, itís not by the literature departments, who have ostracized me;

itís often by the history department or the classics department, because they

recognize my scholarship. They recognize the erudition.

When I was in college, poetry

was radical; there were giant readings. It was just so exciting; we had books of

poetry everywhere. It was part of the culture. I want to bring that back. I want

to give people a feeling of excitement. I want to give people a sense of

confidence. I want to encourage people to go to the library and browse. Go to a

bookstore and browse. Now, who goes to the poetry section of a bookstore? Thatís

why itís good to have National Poetry Month in April, because nobody goes

to the poetry section, unless you know what youíre looking for. When I started

doing this book, I heard throughout the í90s, "Poetryís a flat market. People

are not interested in it at all." So my doing this book is a kind of risk. Iím

putting my reputation on the line. I feel that poetry belongs to everyone, not

just the stupid academic elite, who play their games and do their maneuverings,

with their gigantic salaries; theyíre rip-off artists, from Harvard, Princeton,

Berkeley. The money those people pull down! The pensions! The perks! Itís a

scandal.

I got a really interesting

letter in the early í90s from a woman who said that she had left Berkeley grad

school in English because when she sat at the seminar table and expressed

enthusiasm for what they were discussing, the entire room stopped, everyone

looked at her down their nose. That was just not permissible. These are

going to be undergraduate teachers? You need enthusiasm to connect with

undergraduates who are lost in the media landscape. So what weíve done is driven

out the most imaginative and the best of our future teachers from the

universities, and who are left are these drones. Theyíre like dreary drones who

are just mouthing this fake, leftist stuff. They donít know what theyíre

talking about. Theyíre ass-lickers. Why has the alternative press been so

passive about this for so long? We need to liberate American families and

American students, I say, from the necessity of going to college at all! Why

should anyone have to go to college directly out of high school? Why should they

be on that goddamned hamster wheel, where for the last few years of your

high-school experience, youíre all anxiety about what good school are you going

to? Itís all about status envy, and your parents having the right sticker for

the car. It is a scandal! And the major media, the New York Times

and all the rest of them, have been absolutely cowardly in avoiding this. But

the alternative press has been equally cowardly. The alternative press was

bamboozled by thinking that this fake leftism, which isnít real leftism ó itís

all based on language and deconstruction and so on. It has nothing to do with

real leftism, which is based on social realities and political realities,

historical realities. These people are not historically learned, any of them.

The alternative press did not want to come out on this issue, because it was

inconvenient for them, because of the politics here. Well, thatís great. Thanks

for your lack of balls, the whole alternative press from coast to coast. The

conservatives have gained and gained moral authority over the last 15 years.

They keep gaining and gaining, because they are speaking the truth about how bad

the universities are. Now, I donít agree with their world-view. We needed more

liberals to speak up bravely and to be engaged in the culture war. You asked why

I wrote the book? There it is.

Q:

How do you see the book fitting into your larger body of work?

A:

Sexual Personae, thereís 20-something chapters in it. Thirteen of those

are about poetry. And then a lot of them are about paintings and so on. It goes

from cave art through Egypt and Greece all the way down to Emily Dickinson.

There were a lot of people who went bananas when I came on the scene. I was a

feminist dissident, I belonged to a wing of feminism that had been suppressed

since the í60s, weíd been driven into the wilderness. Well, we returned with a

vengeance in the í90s, thanks to Madonna. We rule now. Andrea Dworkin, Catherine

MacKinnon, all those sense-and-censorship puritans who were on the

required-reading list in the í80s, theyíre gone. Theyíre invisible. We just won,

won, won. When I first came on the scene, though, and was expressing these

criticisms, no one had ever heard of me, and they assumed, "Oh, she must be

conservative, because no one that we could ever respect would

ever criticize feminism." Thatís how elementary their education is ó they

donít understand what an insurgency is. A rebellion against an establishment

thatís become ossified. A social elite run by Gloria Steinem and all of the

womenís-studies programs at the major campuses. They didnít understand that. I

was affirming feminism while demanding change in the way feminism is taught in

the schools or discussed in the media and so forth.

I was so trashed. I mean, it was

really bad. There was a campaign to get me fired from my college. They

were harassing the president of the university. These were all feminist groups!

They were awful. If thatís how they treated me, you can imagine how they

suppressed all kinds of women, silenced them all these decades. Everyone assumed

that they knew what Sexual Personae was about, and ha ha. They

lost. They called me an essentialist. "Sheís an essentialist! Sheís a

positivist!" All these labels. The Village Voice had a vicious

campaign against me for years. At one point I actually went to a lawyer, and we

put a stop to it. I was being defamed as a racist and all kinds of other stuff.

I, who had suffered for so long because of my independent ideas, who could not

get published, to be treated by the alternative press in that way, itís a

scandal. And it shows whatís wrong with this polarization of political

opinion in the United States, where people are in lock step, and theyíre just

not perceiving political issues in a nuanced way. So this is another thing Iím

trying to do here. If the liberal press is truly liberal, then it should show

nuance and imagination in how it treats cultural issues, and stop this

stereotyping.

We need to bring the nuance

back. But I think it has to start on the liberal side, because conservatives are

very, very invested in the Bible and in religious tradition. Youíre not going to

get much flexibility on the conservative side, especially when they feel that

their religious viewpoints are being trashed all the time in the liberal media.

But it is important for the liberal media to start doing a little

soul-searching, and start asking whether its behavior has not worsened

the cultural divide in America, and actually threatens the creation of young

artists, their financial support by the society, and the whole career of being

an artist. We need to get to the European model, where the artist is seen as in

some way embodying the cultural history of the nation. Itís only the liberals

who can do that. So Iím asking liberals: look at this book, and letís get back

to what is quality, what lasts. Letís have a movement that brings art back, the

cultural respect in America. Because itís very, very threatened. The art world

has been totally blind to its own PC leftism. So even though Iím a liberal

Democrat, my primary allegiance is to art and the development of the young

artist.

Q:

In the book you pose the question, where will our future artists come from?

Whatís the answer to that, do you think?

A:

You have to start at the primary-school level. The major universities long ago

abandoned the idea of great art in the canon. The canon has been associated with

conservatives. But I believe in greatness in the arts. Itís very unfashionable

to use the word "greatness." Thatís what a critic should do, determine what is

great and lasting and universal and can speak to the whole world. You may be

very, very interested in certain things in the arts, but is this an essential

work, a work that in the future could represent the age in some way? I think

that the artists of today are trapped in this PR culture, where they feel they

have to make a tremendous shock thing to get attention, and any publicity is

better than none. I say that that is not responsibility to your talent. If you

have a talent, you should withdraw from the chic scene, go someplace, and

develop an artwork or a series of artworks and live with it.

Iím hoping Iím an example,

because for five years, I stayed off the scene to do this book. I can get

publicity if I snap my fingers, but I felt that this is an important topic,

poetry and art in America, and it deserves total devotion. Over the last few

years, [there were] all kinds of things on the Web, like "Pagliaís 15 minutes

are over" and so on. I remember seeing one thing that said, "You mentioned

Camille Paglia. Oh, isnít she like five minutes ago?" That kind of snarky thing.

This is the kind of pressure that young artists feel. I am lucky enough to have

a number of books and have a job teaching at a college, so I could ignore this

kind of pressure, but that is really ruthless. And what that does for the young

artist is it undermines their confidence, the sense that youíve gotta get out

there, gotta get out there. If people really want to contribute to the

history of criticism or the history of literature and art, they need to take

time. I teach in Philadelphia, but I live in the suburbs. I go home. I look at

the trees, I feed the birds. I get invitations all the time, to this event, that

premiere, this and that. I never go. Thereís a lot of people who love to make

that circuit. But you begin to absorb this kind of brittle, artificial thing

that all cities, all great metropolises, always generate, whether it was ancient

Rome or Athens or Renaissance Florence or right down to modern New York. That

social scene is particularly fatal to the aspiring artist now. It wasnít this

bad at all when I was in college. Even in grad school, I was going to Greenwich

Village in the late í60s, early í70s, taking the train down from New Haven. You

really had a sense of the arts and popular culture and hippie stores and

silver-jewelry makers. You just had a sense of a kind of integration of popular

culture and the fine arts. It was just a very exciting time. Now itís awful. I

go to New York, and I can hardly bear to go downtown anywhere. I just

feel everybody is just looking at each other and checking each other out, and

thereís a certain way youíve got to look, you have a code that youíre wearing

that tells what group you belong to, what are your beliefs. No art can come out

of that context. Youíve got to give yourself emotionally to art, youíve got

to.

Q:

Whatís next for you?

A:

I have my third essay collection under contract to Vintage, and it will cover

the period from 1994 to now. And then Iím currently working on a project, and I

donít want to say too much about it, but itís about the visual arts and

Romanticism. I have a piece on plastic surgery coming out in the next

Harperís Bazaar, where I criticize American plastic surgeons for having no

knowledge of art. I say that European and Brazilian plastic surgeons are basing

their surgery on older women on paintings and things like that, but our American

plastic surgeons are basing it on Barbie dolls. So women look awful, older women

look awful. Whereas a Catherine Deneuve, in Europe, looks fabulous. She looks

like a nice, sparkling version of her own age.

Thereís no way to stop the

plastic-surgery movement, I feel. I donít think thereís any way to stop it, and

I wouldnít want to try to stop it, because even though I donít want to do

it ó not unless things get really, really bad, not unless people stop,

horrified, in the street ó I still feel that if people want to reshape

themselves, remodel themselves, itís perfectly legitimate, making yourself a

work of art, et cetera. But I am asking for a rethinking of the models that

weíre using, because, like, Lana Turner, she looked so glamorous in her movies

of the late í50s and early í60s. She looked so good. But she looked like a

beautiful, sensual version of her own age. There was a kind of sexual

maturity that she had. I think that American women who are depending on these

really crass and illiterate surgeons are in a situation which is really bad. A

55-year-old woman should not look like a 25-year-old woman, or not try to,

because thereís no way youíre going to win. A man is always going to want the

25-year-old woman. Instead, you have to add to your power as a woman. You have

to show a knowledge of the world in your face, at the same time being glamorous.

I want people to look at the history of Hollywood and realize how great the

stars looked. The aging stars really handled it well. They werenít made into

nymphets or ingťnues. Thatís what weíre doing now, and itís just horrifying. Iím

a great soap-opera fan, and Iím very alarmed, like on All My Children,

there are these really talented young women, and theyíre really good actresses,

these women canít be older than their early 20s, mid 20s, and they are having

surgery too early. I can see their faces start to get vapid. Itís a

horrible pressure in the TV industry, and in the whole nation at large. Itís not

plastic surgery per se; itís how we are conceiving of the ideal type. The aging

woman should have dignity. Weíre in a very bad period right now.

Rhyme and reason

(Filed:

10/03/2005)

A veteran of the vibrant 1960s poetry scene, Camille

Paglia argues that critics can no longer read, poets can no longer write, and

the unacknowledged legislators of our age are writing advertising jingles for

peanuts

Poetry was at a

height of prestige in the 1960s. American college students were listening to

rock music, but also writing poetry. There were packed readings by poets on

campuses and at political demonstrations. In 1966, for example, I attended an

anti-war "poetry read-in" staged by visiting poets Galway Kinnell, James Wright

and Robert Bly at Harpur College (my alma mater at the State University of New

York at Binghamton). Harpur was then a hotbed of anti-academic poetry. During

graduate school at Yale University, I attended readings by W H Auden, Robert

Lowell, Elizabeth Bishop and many others. In 1969, Allen Ginsberg and Gregory

Corso appeared at the Yale Law School, in an event significantly not sponsored

by the English department, where there was open disdain for Beat poetry (one of

my primary influences).

At that magic

moment, professors specialising in poetry criticism had stratospheric

reputations at the major universities. But over the following decades, poetry

and poetry study were steadily marginalised by pretentious "theory" - which

claims to analyse language but atrociously abuses it. Poststructuralism and

crusading identity politics led to the gradual sinking in reputation of the

premiere literature departments, so that by the turn of the millennium they were

no longer seen, even by the undergraduates themselves, to be where the

excitement was on campus. One result of this triumph of ideology over art is

that, on the basis of their publications, few literature professors know how to

"read" any more - and thus can scarcely be trusted to teach that skill to their

students.

My attraction to

poetry has always been driven by my love of English, which my family acquired

relatively recently. (My mother and all four of my grandparents were born in

Italy.) While my parents spoke English at home, my early childhood in the small

factory town of Endicott in upstate New York was spent among speakers of

sometimes mutually unintelligible Italian dialects. Unlike melodious Tuscan or

literary Italian, rural Italian from the central and southern provinces is

brusque, assertive, and consonant-laden, with guttural accents and dropped final

vowels. What fascinated me about English was what I later recognised as its

hybrid etymology: blunt Anglo-Saxon concreteness, sleek Norman French urbanity,

and polysyllabic Greco-Roman abstraction. The clash of these elements, as

competitive as Italian dialects, is invigorating, richly entertaining and often

funny, as it is to Shakespeare, who gets tremendous effects out of their

interplay. The dazzling multiplicity of sounds and word choices in English makes

it brilliantly suited to be a language of poetry. It's why the pragmatic

Anglo-American tradition (unlike effete French rationalism) doesn't need

poststructuralism: in English, usage depends upon context; the words jostle and

provoke one another and mischievously shift their meanings over time.

English has

evolved over the past century because of mass media and advertising, but the

shadowy literary establishment in America, in and outside academe, has failed to

adjust. From the start, like Andy Warhol (another product of an immigrant family

in an isolated north-eastern industrial town), I recognised commercial popular

culture as the authentic native voice of America. Burned into my memory, for

example, is a late-1950s TV commercial for M&M's chocolate candies. A sultry

cartoon peanut, sunbathing on a chaise longue, said in a twanging Southern

drawl: "I'm an M&M peanut / Toasted to a golden brown / Dipped in creamy milk

chocolate / And covered in a thin candy shell!" Illustrating each line, she

prettily dove into a swimming pool of melted chocolate and popped out on the

other side to strike a pose and be instantly towelled in her monogrammed candy

wrap. I felt then, and still do, that the M&M peanut's jingle was a vivacious

poem and that the creative team who produced that ad were folk artists,

anonymous as the artisans of medieval cathedrals.

My attentiveness

to the American vernacular - through commercials, screwball comedies, hit songs,

and talk radio (which I listen to around the clock) - has made me restive with

the current state of poetry. I find too much work by the most acclaimed poets

laboured, affected and verbose, intended not to communicate with the general

audience but to impress their fellow poets. Poetic language has become stale and

derivative, even when it makes all-too-familiar avant garde or ethnic gestures.

Those who turn their backs on media (or overdose on postmodernism) have no gauge

for monitoring the metamorphosis of English. Any poetry removed from popular

diction will inevitably become as esoteric as 18th-century satire (perfected by

Alexander Pope), whose dense allusiveness and preciosity drove the early

Romantic poets into the countryside to find living speech again. Poetry's

declining status has made its embattled practitioners insular and

self-protective: personal friendships have spawned cliques and coteries in book

and magazine publishing, prize committees and grants organisations. I have no

such friendships and am a propagandist for no poet or group of poets.

In my new book,

Break, Blow, Burn, I offer line-by-line close readings of 43 poems, from

canonical Renaissance verse to Joni Mitchell's Woodstock, which became an anthem

for my conflicted generation. In gathering material, I was shocked at how weak

individual poems have become over the past 40 years. Our most honoured poets are

gifted and prolific, but we have come to respect them for their intelligence,

commitment and the body of their work. They ceased focusing long ago on

production of the powerful, distinctive, self-contained poem. They have lost

ambition and no longer believe they can or should speak for their era. Elevating

process over form, they treat their poems like meandering diary entries and

craft them for effect in live readings rather than on the page. Arresting themes

or images are proposed, then dropped or left to dribble away. Or, in a sign of

lack of confidence in the reader or material, suggestive points are prosaically

rephrased and hammered into obviousness. Rote formulas are rampant - a

lugubrious victimology of accident, disease, and depression or a simplistic,

ranting politics (people good, government bad) that looks naive next to the

incisive writing about politics on today's op-ed pages. To be included in this

book, a poem had to be strong enough, as an artefact, to stand up to all the

great poems that precede it. One of my aims is to challenge contemporary poets

to reassess their assumptions and modus operandi.

In the 1990s,

poetry as performance art revived among young people in slams recalling the

hipster clubs of the Beat era. As always, the return of oral tradition had folk

roots - in this case the incantatory rhyming of African-American urban hip-hop.

But it's poetry on the page - a visual construct - that lasts. The eye, too, is

involved. The shapeliness and symmetry of the four-line ballad stanza once

structured the best lyrics of rhythm and blues, gospel, Country and Western

music, and rock'n'roll. But with the immense commercial success of rock music,

those folk roots have receded, and popular songwriting has grown weaker and

weaker.

My title comes

from a poem in this book, John Donne's "Holy Sonnet XIV": "That I may rise, and

stand, o'erthrow me, and bend / Your force, to break, blow, burn and make me

new." Donne is appealing to God to overwhelm him and compel his redemption from

sin. My secular but semi-mystical view of art is that it taps primal energies,

breaks down barriers and imperiously remakes our settled way of seeing. Animated

by the breath force (the original meaning of "spirit" and "inspiration"), poetry

brings exhilarating spiritual renewal. A good poem is iridescent and

incandescent, catching the light at unexpected angles and illuminating human

universals - whose very existence is denied by today's parochial theorists.

Among those looming universals are time and mortality, to which we all are

subject. Like philosophy, poetry is a contemplative form, but unlike philosophy,

poetry subliminally manipulates the body and triggers its nerve impulses, the

muscle tremors of sensation and speech.

The sacred

remains latent in poetry, which was born in ancient ritual and cult. Poetry's

persistent theme of the sublime - the awesome vastness of the universe - is a

religious perspective, even in atheists like Shelley. Despite the cosmic vision

of the radical, psychedelic 1960s, the sublime is precisely what

poststructuralism, with its blindness to nature, cannot see. Metaphor is based

on analogy: art is a revelation of the interconnectedness of the universe. The

concentrated attention demanded by poetry is close to meditation.

Commentary on

poetry is a kind of divination, resembling the practice of oracles, sibyls,

augurs, and interpreters of dreams. Poets speak even when they know their words

will be swept away by the wind. In college Greek class, I was amazed by the

fragments of Archaic poetry - sometimes just a surviving phrase or line - that

vividly conveyed the personalities of their authors, figures like Archilochus,

Alcman and Ibycus, about whom little is known. The continuity of Western culture

is demonstrated by lyric poetry.

Another of my

unfashionable precepts is that I revere the artist and the poet, who are so

ruthlessly "exposed" by the sneering poststructuralists with their political

agenda. There is no "death of the author" (that Parisian clichť) in my world

view. Authors strive and create against every impediment, including their

doubters and detractors. Despite breaks, losses and revivals, artistic tradition

has a transhistorical flow that I have elsewhere compared to a mighty river.

Poems give birth to other poems. Yet poetry is not just about itself: it does

point to something out there, however dimly we can know it. The modernist

doctrine of the work's self-reflexiveness once empowered art but has ended by

strangling it in gimmickry.

Artists are

makers, not just mouthers of slippery discourse. Poets are fabricators and

engineers, pursuing a craft analogous to cabinetry or bridge building. I

maintain that the text emphatically exists as an object; it is not just a mist

of ephemeral subjectivities. Every reading is partial, but that does not absolve

us from the quest for meaning, which defines us as a species. In writing about a

poem, I try to listen to it and find a language and tone that mesh with its own

idiom. We live in a time increasingly indifferent to literary style, from the

slack prose of once august newspapers to pedestrian translations of the Bible.

The internet (which I champion and to which I have extensively contributed) has

increased verbal fluency but not quality, at least in its rushed, patchy genres

of e-mail and blog. Good writing comes from good reading. All literary criticism

should be accessible to the general reader. Criticism at its best is

re-creative, not spirit-killing. Technical analysis of a poem is like breaking

down a car engine, which has to be reassembled to run again. Theorists

childishly smash up their subjects and leave the disjecta membra like litter.

For me, poetry is

speech-based and is not just an arbitrary pattern of signs that can be slid

around like a jigsaw puzzle. I sound out poems silently, as others pray. Poetry,

which began as song, is music-drama: I value emotional expressiveness, musical

phrasings, and choreographic assertion, the speaker's theatrical

self-positioning toward other persons or implacable external forces. I am not

that concerned with prosody except to compare strict metre (drilled by my Greek

and Latin teachers) to the standard songs that jazz musicians transform: I

prefer irregularity, syncopation, bending the note.

My advice to the

reader approaching a poem is to make the mind still and blank. Let the poem

speak. This charged quiet mimics the blank space ringing the printed poem, the

nothing out of which something takes shape. Many critics counsel memorising

poetry, but that has never been my habit. To commit a poem to memory is to make

the act of reading superfluous. But I believe in immersion in and saturation by

the poem, so that the next time we meet it, we have the thrill of recognition.

We feel (to quote

singer Stevie Nicks) the hauntingly familiar. It's akin to addiction or to the

euphoria of being in love.

This is an edited version of the introduction to 'Break,

Blow, Burn: Camille Paglia Reads Forty-Three of the World's Best Poems',

published by Pantheon Books

June 11, 2005

THE SATURDAY

READ

Reviving the love of poetry

By Jerry

Griswold, Special to The Times

Break, Blow,

Burn: Camille Paglia Reads Forty-Three of the World's Best Poems

Camille Paglia

Pantheon: 252 pp., $20

Camille

Paglia's radical agenda is to win undergraduates (and the general public) back

to poetry. Who better to do this than the renegade literary critic and author of

"Sexual Personae," who showed she could take up Emily Dickinson and Madonna in

the same sentence, this cultural spokeswoman and media celebrity whose name

appears in her new book's subtitle.

In "Break, Blow, Burn," Paglia contends that poetry has fallen on hard times in

the United States. Contemporary poets, subsidized by self-interested and

academic cliques, have become affected and precious. Poetry readings are

exercises in narcissism; even the current craze of "slams" amounts to a pathetic

bid for attention by annexing poetry to hip-hop.

But the real

culprit in poetry's demise is a new generation of professors who have sold their

souls to Jacques Derrida and other effete French critics. Venerating

theory-about-poetry over poetry itself, these solipsists bore students with

their quasi-scientific mumbo jumbo. The love of poetry is in danger of being

lost.

As a corrective, Paglia considers 43 poems and, in short essays of lucid prose,

parses them and intelligently explains their meaning. Mixing the canonical with

the contemporary, her choices include Shakespeare's sonnets and Joni Mitchell's

song "Woodstock." This last choice is revealing. Paglia means to bring back the

1960s and '70s.

I remember those days. When hundreds of us would pack an auditorium to hear

Allen Ginsberg read poetry. When radicalism and poetry went hand in hand. When

Sylvia Plath was avant-garde. When Dick Cavett's television guests included Jimi

Hendrix and W.H. Auden.

In clamoring to bring back those days, then, is Paglia's agenda really radical

or reactionary? At first glance, the poets she chooses (e.g., Donne, Herbert,

Shelley, Lowell and Roethke) and the poems she examines (e.g., Dickinson's

"Because I Could Not Stop for Death," Yeats' "The Second Coming" and Williams'

"The Red Wheelbarrow") seem standard choices for a neo-con or classical

anthology designed by, say, William Bennett. But Paglia mixes in some

contemporary choices (Plath's "Daddy," for example) and makes the furious point

in her introduction that the love of poetry is a radical act of cultural

recuperation in the face of current mores and mediocrity.

I'm not sure my undergraduate students would buy this. They would easily size

her up: the aging '60s radical, the professor willing to wear a leather bustier

to class to stir Generation X-ers from their apathy and get them reading poetry.

And if the truth be known, after the pugnacious radicalism of the introduction,

this book is not that flamboyant; instead, it is a solid and impressive

achievement that stands with the very best American writing on poetry by Helen

Vendler and Randall Jarrell. Although such a compliment might unnerve someone

whose notoriety rests on being a renegade, Paglia has no reason to be

embarrassed that "Break, Blow, Burn" sheds more light than it does heat.

However, it is disconcerting when an accomplished critic such as Paglia misses

the Big Clue that would get us to the target more directly. For example, she

interprets this part of Gary Snyder's poem "Old Pond":

At Five Lakes Basin's

Biggest little lake

after all day scrambling on the peaks,

a naked bug

with a white body and brown hair

dives in the water,

Splash!

These lines prompt Paglia to make an eccentric connection between Snyder's

comparison of himself as a bug and Kafka's character Gregor Samsa changing into

an insect. Snyder's swimming oddly reminds her that the poet Byron was also a

swimmer. Somewhat closer to the point, a quiet lake recalls to her the still

mind sought in Buddhism. These are only a few of many fevered associations

Paglia makes in a busy paragraph that begins with the question: What are we to

make of the title of Snyder's poem "Old Pond"?

But the answer is simple: Snyder is a longtime student of Japanese Zen, and his

poem echoes the well-known poem with the same title by the monk Basho:

The old pond;

A frog jumps in ó

[Splash!] The sound of water.

It's embarrassing that she doesn't seem to recognize this. As author and Zen

master Robert Aitken observed, "This is probably the most famous poem in Japan."

This haiku is also a standard entry in many literature textbooks.

The old pond. A critic jumps in. [Oops!] The sound of falling short.

Jerry Griswold, who teaches undergraduates at San Diego

State University, is the author of "The Meanings of 'Beauty and the Beast': A

Handbook."

Poetic Personae

Reviewed by Stephen Burt

Sunday, July 31, 2005; BW12

BREAK, BLOW, BURN

By Camille Paglia

Pantheon. 247 pp. $20

A volcanic

mountain has labored, and brought forth a mouse: The sexy celebrity bad-girl

cultural critic of the '90s has produced a flawed but serviceable brief

textbook.

A

professor at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia, Camille Paglia won

acclaim and even notoriety with Sexual Personae (1990) whose 700-plus

pages emphasized the "amorality, aggression, sadism, voyeurism and pornography

in great art," from prehistory to Emily Dickinson and Henry James. Since then

she has become a prolific commentator on popular culture and film. By these

standards, Break, Blow, Burn is modest: It tries to introduce good,

accessible short poems in English and to help readers enjoy them as Paglia does.

That is

what good teachers do, and the first three-quarters of the book follows through,

offering patient, vigorous and largely uncontroversial explication of poems by

Shakespeare, Donne (whom her title quotes), Wordsworth, Coleridge and others.

Obsolete double meanings, obsolescent things (a root cellar, for example) and,

especially, biblical references need old-fashioned explanations, which Paglia

provides with skill.

She also

proves entertainingly willing to say not only what a poem does and means, but

why she likes it. Some sentences sound outrageous but in fact offer imaginative

guidance, as when Paglia imagines William Blake roaming London "with telepathic

hearing and merciless X-ray eyes" or explains Walt Whitman's universe as "a

plush matrix or webwork of gummy secretions."

It's hard

to show introductory-level students how poems speak to one another across

generations when those students come to class having read so few. Paglia

surmounts that problem by comparing the poems she's chosen to one another, even

when such comparisons may not be what the poets had in mind.

Her

obsessions can interfere with her aims. Paglia sees paintings or movies almost

every time she looks at a poem. Shakespeare has "a Mannerist sophistication";