22-6-2001

A Família

McCourt

Frank McCourt

died

on 19-7-2009.

| |

|

NOTA DE

LEITURA

Mais

um McCourt que se dedica à escrita? Talvez não. Mas o respeitável

The Washington Post acaba de publicar um artigo do irmão mais novo

de Frank e de Malachy, Alphie, intitulado “Mam’s Boy”, sobre

a mãe Ângela, falecida em Nova York em 1981 (reproduzido a

seguir).

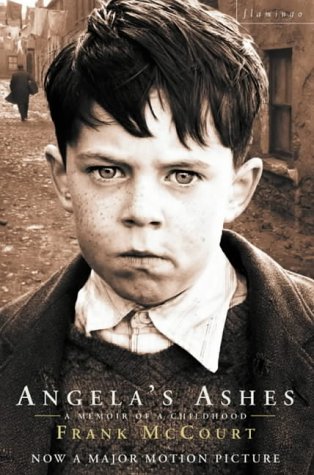

Li

de rajada “Angela’s Ashes”, “’Tis” e “A monk swimming”,

os primeiros dois de Frank

e o último de Malachy. O primeiro vendeu milhões de exemplares, após

ter ganho o Prémio Pulitzer. Dele

foi extraído um filme com o mesmo título, que teve um sucesso

moderado, talvez por

seguir o livro demasiado à letra. O segundo livro, ‘Tis, foi mal recebido pela crítica.

Falta-lhe o impacto do primeiro, que descrevia uma miséria de que não

é de bom tom falar.

“A

monk swimming”, de Malachy, deve o título à Ave Maria, deformada pela mente

do autor em criança: “Blessed are thou 'amongst women'”.

Nem

toda a gente gostou dos livros dos McCourt. Desde logo, a maior

parte dos irlandeses, que não gostaram de ver tão difundida uma

versão da Irlanda miserável do tempo da guerra e do após-guerra,

para além de um feroz retrato do pai, alcoólico inútil e

inveterado. Depois, os

católicos ferrenhos, que não aceitam a ideia de que o catecismo não

tem qualquer valor como educação infantil.

Finalmente, também uma boa parte do público leitor

feminino; não sendo misóginos, os McCourt são bastante severos

com a sua mãe e com uma parte das mulheres com quem viveram.

Entretanto,

embora o sucesso tenha chegado bastante tarde na vida, Frank

continua a escrever. O artigo reproduzido a seguir, do Sunday Times, dá conta

dos seus projectos, aos 71 anos de idade!

|

|

|

| |

|

Produção

dos McCourt

Frank

McCourt

As

cinzas de Ângela, Editorial Presença, 1997

Esta

é a minha terra, Editorial Presença, 2000

Teacher Man, 2005

Malachy

McCourt

A

monk swimming, Hyperion, USA, 1998

Singing

My Him Song, Harper Collins, 2000

Danny Boy, New

American Library, 2002

Conor

McCourt (polícia, filho de Malachy)

The

McCourts of Limerick, documentário, 1998

IMDB

The

McCourts of New York, documentário, 1999, IMDB

|

|

|

| |

|

Mam's

Boy

By Alphie McCourt

Special to The Washington Post

Sunday, May 13, 2001

I live in New York City.

Early on a Thursday evening, in April of this year, I went for a walk. My

wife, Lynn, was working late; my daughter, Allison, well cared for. I was

a free man for a few hours.

From the West Seventies I

walked, up Amsterdam Avenue, across West 96th Street and on down Broadway,

stopping at a bookstore for a 15-minute browse, stopping again for a

sandwich, a coffee and an extended read of the newspaper.

It had started to rain,

large tropical drops coming in spurts, turning now into a steady drizzle.

When my head and feet are protected I enjoy walking in the rain. Rain

brings on the melancholy. Unlike the cement block that is depression, a

decent melancholy is liquid. The pleasure of walking in the rain brings on

a cheerful, a most satisfying melancholy. My mother loved to walk in the

rain.

Across West 72nd Street I

walked, heading toward Columbus Avenue and home. West 72nd is a busy

street, always teeming with people. Everything is for sale: bagels, drugs,

roller blades, toothpaste, a cheap divorce, videocassettes, wine, food,

shoes, real estate, papaya juice and instant fitness. I took note of two

stores, side by side, both for rent. One had been a florist's shop, the

other a funeral home. We often drive through small towns in New Jersey.

All too often the most imposing house in the downtown area turns out to be

the funeral home. Funeral homes do not go out of business but this one on

72nd Street had closed. Walking past it in the rain, I thought of Mam.

I grew up in Limerick

City, Ireland, in the 1940s. Our family circumstances were terrible, due

in large part to my father's absence. He left when I was a year old. When

I was 5 we moved to Rosbrien, on the outskirts of Limerick, to the house

of my mother's cousin Gerard Griffin. It was a mean house.

When Mam was in the house

it was bearable but she was gone for long periods during the day, working,

maybe, or trying to cadge something in the way of food. When she was gone

it was cold and damp, wet and bleak. My older brother Mike and I played

outside in the cold and the wet, or inside, in the damp.

Play we did, engage we

did, but we were always hungry. We would wait for Mam to come home to

light fire and lamp if we had coal and oil and to cook if she had found

any food.

In Northern Ireland they

would have called us "scaldies," little birdies in the nest,

beaks wide open, waiting for father or mother to bring food. Whatever Mam

brought she brought herself. To me she brought the world.

In 1981, more than 30

years later, I went to visit her in Lenox Hill Hospital in New York. She

had emphysema. Mam always had respiratory problems, a condition hereditary

among her family, the Sheehans. The Sheehan chest, we called it.

Breathing for her was a

careful business. Mam liked to plant flowers but she believed that plants

took more than their share of the air in a room. (Plants, their secret

lives, their craving for frequent injections of classical music, were of

little concern to her. I once heard a young woman ask her, "Mrs.

McCourt, do you have any plants?" "No." said Mam, "I

live alone.")

I had had no conversation

with doctors or nurses but I knew that she was very sick. It was time to

tell her what she had brought to me when I was a child, even when there

was nothing, or almost nothing, to bring. Words would not come. I tried to

speak, tried to tell her, choked, tried again and choked again. Mam didn't

need me crying at her bedside. She said she craved something "tarty."

I bought her some lemon drops, kissed her and said goodbye. I never did

tell her. Four days later she died.

Within the family it was

said that I didn't talk much, that I would never tell. When I was 7 the

brothers hung me up on a nail in a closet by the back of my collar.

Hide-and-seek went on all around me. I made no sound and was not found

until they came and got me.

In 1996, 15 years after

my mother's passing, Lynn and I visited my brother Frank and his wife,

Ellen, in Pennsylvania. Frank told us that he had been to see my mother in

the hospital on the same day that I had been there. Mam had told him of my

visit and of my silence. She didn't expect me to talk and was not

surprised when I didn't. "Old chatterbox was here," was all she

said. Never would she know how desperately I had tried.

The now out-of-business

funeral home on West 72nd Street was her last resting place in New York.

We gathered, family and friends, for the wake. The long, austere, orderly

pews are designed for mourning and for whispers, if not for complete

silence. We arranged them in a circle, our wagons against the gloom.

Funeral homes are not for singing but sing we did and told the stories and

sang again the songs she liked. Cremation was her choice, in an anonymous

crematorium in New Jersey. I collected the urn containing her ashes. My

brothers Frank and Malachy took it to Ireland and scattered her ashes in

the burial ground in Mungret Abbey outside of Limerick. Mam's mother and

brother are buried there. Nearly a thousand years old, Mungret is now a

national shrine, with no more burials permitted. Mungret Abbey is not

likely to go out of business, to undergo development or to be overrun by

an army of plants. And there is plenty of rain.

©

2001 The Washington Post Company

|

|

|

| |

Everyone knows the troubles he's seen . . .

'Tis

a fine life, to be an Irish writer in New York, with a Pulitzer prize in

your pocket and millions of hungry readers hanging on your every anecdote.

For a man who suffered an epically tormented Limerick childhood - then

waited 40 years to describe it in a triumphant memoir of hunger, disease

and aching family loss - Frank McCourt is making the most of a gilded old

age. The author of Angela's Ashes and 'Tis must rank among the busiest

70-year-old writers in the world.

He's off to England soon, to

talk about his writing at the

Sunday Times Hay Festival. He is just back from Bombay and a cruise down

the Nile, where a couple of lectures on board ship earned him a visit to

Luxor and the pyramids. Last week he was in upstate New York, receiving an

honorary degree, his ninth.

Then

there are his literary commitments. "My wife just set up a file

drawer called Frank's Projects," he chortles with relish.

He

wants to rewrite a play he wrote a couple of years ago about "the Irish and

how they got that way".

|

|

He

has contributed a masterful denouement to Yeats Is Dead, a "crazy"

serial novel, to be published next month in aid of Amnesty International, in

which a dozen or so Irish writers take it in turns to write chapters of

spiralling improbability.

He

is collaborating on a church mass, Missa Manhattan, something he has wanted to

create ever since he heard Missa Luba, an African- inspired interpretation of

Catholic liturgy.

And

he is talking to a friend, a television producer, about making a documentary on

saints. Anyone who has read Angela's Ashes knows McCourt is fascinated by saints.

"Virgin martyrs especially," he grins.

All

of which pales to inconsequence compared to the real reason McCourt is looking a

little worn as he arrives at a high-rise Manhattan studio to have his picture

taken. He is about to face one of the world's most formidable photographers, but

his silver hair is uncombed, his grey suit rumpled, his shirt open at the neck,

and slightly askew.

He

looks as though he has just stumbled out of bed, but the truth is the opposite.

He has been up for hours, working on the book that is propelling Frank McCourt

in an entirely new literary direction - away from hypnotising accounts of family

blight, dying mothers and Irish poverty into the boundless realm of a fictional

New York school.

McCourt

is writing his first novel. "It's about the chemistry of teaching," he

says, "about the process, the conditions, the circumstances of teaching.

And it's much harder. I'm not just dipping into my memory, I'm creating."

He

had sat there earlier that morning, in his favourite writing chair, with a board

across the arms in front of him, scribbling away in his notebook, fighting to

resist the siren call of the life that filled his first two books. "This

novel is trying to drag me off in another direction, to Ireland, and I don't

want to go there. Not for the moment, anyway. I want to stay in the classroom."

He

hardly lacks for material in New York. Having left Ireland as a teenager,

McCourt served with the US military in Germany and studied at New York

University under the provision of the GI Bill, which encouraged education of

soldiers - "the most glorious piece of legislation ever passed in this

country," he says. After four years he became a teacher, and remained one

until his retirement in 1987.

"The

average American saw the Irish as a simple people, just off the land with mud on

their boots," he says. "When I arrived in New York, I didn't know the

difference between asparagus and turnips. But dogged is the word. I was not

particularly bright, but dogged."

With

a characteristic McCourt flourish, he recalls his first day as a teacher: "It

was the middle of March, the teacher I was replac- ing had quit, I walked into

the classroom and they were all throwing things across the room. After four

years of studying education at New York University, the first words out of my

mouth as a new teacher were: 'Stop throwing Bologna sandwiches.' "

McCourt

believes that teaching has never been properly written about in a novel, not in

Tom Brown's Schooldays, Goodbye Mr Chips or any number of tales of English

public schools. He evidently wants to do for the profession what Angela's Ashes

did for Irish poverty.

"Teaching

is virgin territory for a writer," he says. "It's very difficult to

write about the chemistry of the relationship with the 35 kids you want to teach,

when they are resisting. This is the drama, the tension of the profession.

You've resisted your own boring classes elsewhere, you know the nature of

resistance and it's up to you now to get through."

So

is the hero of his novel, by any chance, going to be a tall, handsome Irishman

who endured a difficult childhood in Limerick? "Oh yes," jokes McCourt.

There will be sufficient parallels with his own life for lawyers to be called in

to scrutinise the manuscript, notably for references to McCourt's first wife,

Alberta, who does not appear to have forgiven him for the way he portrayed her

in Angela's Ashes.

"I

have to be careful because there are people still alive who taught with me, and

I have ex-wives, there's a parallel in the novel between the teaching and the

domestic life," says McCourt. "A lot of lawyers will be hired for a

careful textual read."

As

he spins out the anecdotes from his teaching days - cajoling his kids into

reading Shakespeare, making hard-boiled New York teenagers chant Mother Goose

nursery rhymes, and singing Finnegans Wake in class - it seems clear that in

style and texture, the new novel may not be too different from 'Tis, which

covered some of McCourt's early life as a teacher in America.

Judgment

will be reserved on whether that is a good omen. McCourt knows that the success

of Angela's Ashes owed most to his lyrical evocation of a real and desperate

boyhood in Limerick. 'Tis, the sequel set in New York, sold well, but was

derided by several critics. Can he create something as memorable as either book

in fiction?

"When

I look back at the writing of Angela's Ashes, I was just telling a story in the

simplest possible way, because that's all I'm capable of," he modestly

declares. "I could never be a Proust or even an Evelyn Waugh or anyone like

that. I could never have that subtlety and complexity and cleverness."

He

is also wary of repeating himself. His youngest brother, Alphie, recently became

the third McCourt brother - after Frank and Malachy - to write about their

mother's death, in an article for the Washington Post. "I thought Alphie

might write about something different, but he didn't," says McCourt,

smiling wanly. "I'm so weary of the family stuff, the dying mothers and so

on."

But

mostly, he's not weary at all. "You know I could always go and sit on a

beach in the south of France and look at the bare-breasted beauties passing by,"

he muses. "I could have done the same thing after Angela's Ashes. You might

have thought, he's done it, Jesus, this old fart after 30 years, he writes a

book and gets the Pulitzer prize, that's enough, let him give himself a break."

His

eyes shine. "But it's the story-telling itch, I suppose, and the teaching

itch. You can't stop. Besides, I enjoy it."

Tony

Allen-Mills

The

Sunday

Times, 27-5-2001

From

http://www.spiked-online.com

21 June 2001

Frank about memoirs

by

Brendan O'Neil

I have spent five years immersed in myself, my life,

my squalor, my ups, my downs - and now I'm feckin gasping for air.'

Frank McCourt, dirt-poor Irish kid done good, wants

to write fiction. Having told the world about his 'miserable Irish childhood' in

1930s Limerick in Angela's Ashes and

about his adventures in New York in the follow-up

'Tis, he now wants to prove that

'there's more to Frank McCourt than feckin Frank McCourt'. 'I'm tired of telling

my life story. I long to write a thriller or a romp or a story from the point of

view of a woman or a gay Irishman. You know, just to turn things on their head.'

But why not stick to a winning formula?

Angela's Ashes might have been a

'sometimes painful experience' for McCourt, but it sold five million copies and

counting, was made into a film by Alan Parker, won its first-time author a

Pulitzer Prize, and earned him a house up the road from US playwright Arthur

Miller ('Jesus, it's weird having a neighbour who was hitched to Marilyn Monroe',

says McCourt). 'Tis might have been

less of a hit with the critics, but it was another transatlantic bestseller. And

as one critic said, 'There's gold in them there memoirs'.

But there's only so much life you can write about', says McCourt. 'Before long,

you run out of life. I want to exercise my imagination in a different way. With

Angela's Ashes and

'Tis I was never interested in

glorifying myself - I just wanted to tell my story, to tell the truth as I

experienced it. Now I want to write about some glory or other, with heroes and

fictional characters. It would make a change from writing about me and my

brothers and my father leaving and my mother dying and the consumption killing

people left right and centre and the shoes falling off my feet. I'm grateful for

what the memoirs gave me - but it's fiction for me now.'

But McCourt has his detractors - like those who reckon he's been writing fiction

all along. Angela's Ashes may have

been A Phenomenon, but there was also The Backlash - with the book provoking the

kind of vitriolic reaction that hasn't greeted a personal memoir since Christina

Crawford accused her actress mother Joan of child abuse in

Mommie Dearest in the 1980s. For

every review and article hailing McCourt as a great writer, there seemed to be

somebody ready and willing to accuse him of exaggeration, 'anti-Limerickness',

or of telling downright lies. 'Ah yeah', says McCourt, 'the backlash'.

According to some reports, there was a book-burning

atmosphere in McCourt's childhood home of Limerick. Gerry Hannan, a dj on

Limerick 95 radio station, achieved minor celebrity status as McCourt's most

outspoken critic, collating a book of memories from the people of Limerick that

contradicted McCourt's version of events, and challenging McCourt to sue him if

he had the guts ('See you in court, McCourt' was his fighting talk). And when

Alan Parker and his crew descended on Limerick to film scenes for the celluloid

version of McCourt's life, some claim they were chased out of churches and

streets by anti-Angela's Ashes mobs.

But McCourt is having none of it. 'The stuff about people being hostile to me in

Limerick is completely and utterly blown out of proportion', he says. 'It was

actually a very small, very concentrated, very localised reaction, and the media

pumped it up.' So when I ask if he ever ventures into Limerick now - thinking

that the last place in Ireland you would want to be unpopular is 'Stab City' -

McCourt sounds aghast. 'Of course I do. I was there just two weeks ago - and I

always get a warm response. I wish I could peddle some grand line about prophets

not being recognised or accepted in their hometowns, but I'm afraid it just

wouldn't be true.'

According to McCourt, 'the negative stuff has been

given too much ink': 'The media loves a backlash because it makes good copy.

They didn't want to write about the fact that

Angela's Ashes and

'Tis sold thousands in Limerick; that

when they made the film people swarmed out in their hundreds to be extras; that

I got an honorary degree from the University of Limerick; that I was received at

the City Hall by the mayor; that the city has an

Angela's Ashes tour that draws people

in from around the world. But a few disgruntled accusations? Hold the front

page!'

McCourt says the Limerick authorities even wanted to

put a plaque on his childhood home - until they realised it no longer existed.

'All the old slums are gone', says McCourt. 'You can't find a decent slum in

Ireland anymore.'

But if the scale of the accusations was 'pumped up',

what about their content - that McCourt has twisted the truth, or even lied

about his childhood? Some argue that it's impossible for a 65-year-old (McCourt's

age when he wrote Angela's Ashes) to

recall so vividly conversations and events that happened when he was six, seven

or eight. While others claim that life might have been hard in Limerick in the

1930s, but it wasn't as bad as McCourt makes out (children dying from cold and

starvation, mothers begging priests for leftover bread), and that there was more

kindness in the city than McCourt suggests. So is

Angela's Ashes the whole truth and

nothing but?

McCourt thinks his critics are missing the point. 'Angela's

Ashes and 'Tis are not

autobiographies, they are memoirs - and they are not the same things. An

autobiography is an attempt to bring up all the facts, and to stick to them,

faithfully and chronologically. But a memoir is an

impression of your life, and that

gives you a certain amount of leeway. If an autobiography is like a photograph,

then a memoir is more like a painting. So I've always said to my critics, This

is my impression of my life, so what are you gonna do about it?'

For McCourt, memoirs have more in common with fiction

than with journalistic fact or autobiography. 'Memoir is like the twin sister of

fiction', he says. 'There is a crossover between recalling events that actually

happened and your interpretation or impression of those events. This doesn't

make it dishonest; it is just what the genre is about. If people want absolute

fact they should stick to autobiographies - or the

National Geographic.'

So what does McCourt think of today's memoir mania,

that some say he is responsible for? 'Don't blame me!' But walk into any

bookshop and you'll see shelves groaning under the weight of memoirs - and it

sometimes seems that the authors are competing to see whose life was the most

degraded and depressing. There are child-abuse memoirs, eating-disorder memoirs,

and, of course, the miserable Irish childhood memoir. In the wake of

Angela's Ashes, the miserable Irish

childhood memoir has almost become a genre in its own right - with even two of

McCourt's brothers offering their own versions of the McCourt upbringing.

There are lots', says McCourt, 'that's for sure. But I don't think it's really a

"memoir mania". Nobody ever complains about a "fiction mania" do they? But there

does sometimes seem to be this tortured approach in memoirs - my life was harder

than yours, my pain is bigger than yours. I know that's a bit much coming from

me, after Angela's Ashes and all -

but one of the good things about a memoir is looking for something bigger than

yourself, you know; something important in your life, rather than just the life

itself.'

But finally McCourt is moving on, and turning his hand to fiction. 'I'm trying

to write a novel about teaching. It's very early days - it's not even in its

embryonic stages yet, it's still waiting to be conceived.

'And who knows, it might end up as a memoir.'

Frank McCourt

has written chapter 15 in Yeats is Dead!,

a new multi-authored novel by 15 Irish writers published by Jonathan Cape.

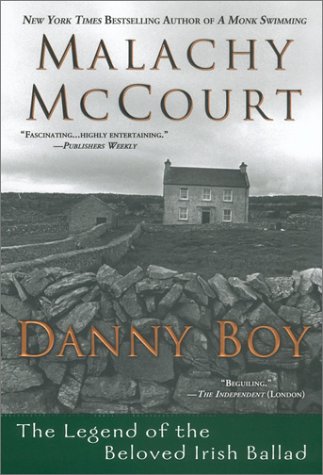

DANNY BOY: The Beloved Irish Ballad

Malachy McCourt

New American Library

Nonfiction

ISBN: 0451208064

|

Beyond question, the melody

variously known as "Danny Boy" or "Londonderry Air" is one of the great tunes of

all time. Its measured rising and falling cadences would grace the catalog of

Franz Schubert or any of the other great classical vocal composers.

Malachy McCourt, brother of novelist Frank McCourt (ANGELA'S ASHES) and a

well-known writer and radio-TV luminary in his own right, has produced a curious

little book of less than 95 pages about the famous tune and its well-known

lyrics. His book is part history, part speculation, part myth and part personal

editorial essay. And it is not free from touches of Irish blarney.

McCourt's findings may surprise --- and dismay --- many. The great tune, long

since adopted as a kind of unofficial Irish national anthem, may not be of Irish

origin. A folklorist named Jane Ross supposedly first noted it down around 1851.

She reportedly heard it played by a blind fiddler, Jimmy McCurry, in Limavady,

Londonderry --- but there is at least a possibility that the melody may have

originated in Scotland. No one knows for sure. At least one respected musical

scholar claims that the tune follows no known metric scheme for Irish folk

music. |

|

|

|

Many different sets of words

were attached to the tune after its first publication in 1855 --- but those that

have become indissolubly identified with it ("O Danny boy, the pipes, the pipes

are calling, from glen to glen and down the mountainside....") were written in

1910 by an English lawyer and song-lyric cobbler named Frederick E. Weatherly,

who probably never set foot in Ireland.

They were actually intended for a different tune, but when Weatherly's

sister-in-law sent him some years later the familiar melody from her home in

Australia, he saw that it was a perfect fit for his earlier verses. Thus an

"Irish" classic was created from a melody that may be Scottish and words by an

Englishman.

McCourt gives us this information straightforwardly enough, but he fleshes them

out with a good deal of barely relevant material. It seems strange to arraign a

book of 95 pages on charges of padding, but the complaint seems justified.

McCourt solicited opinions about the song from Irish celebrities (including

brother Frank) and speculates at length on such side issues as who is singing

the song and to whom it is addressed (one possibility among several: it is the

song of Danny Boy's gay lover!). The author's tone varies between straight

historical writing and folksiness, including occasional cutesy use of "tis" and

"t'was." McCourt also grinds a personal axe or two. He thinks ill of those

Catholic dioceses that have banned the singing of "Danny Boy" at funerals

because it is "secular."

There are some fascinating bits of trivia here, however. Victorians hesitated to

refer to the song as Londonderry Air because, to their prudish ears, it sounded

too much like "London

derriere." Irish nationalists never use that title either, because they want no

mention of London in the title. Wordsmith Weatherly was once in legal

partnership with one of the sons of Charles Dickens. And another of Weatherly's

lyrics was the popular "Roses of Picardy," set to music memorably by Haydn Wood.

Wood studied under the composer Sir Charles Stanford, who quoted "Londonderry

Air" in one of his Irish rhapsodies. Make of that what you will. This is a

curious little book, entertaining in its quirky way but almost undone by its

relentless folksiness. "Londonderry Air" remains a musical treasure, regardless

of its origin.

--- Reviewed by Robert Finn (Robertfinn@aol.com)

Apr. 4, 2004 9:45

Irish eyes are smiling

By

MIRIAM ABRAMOWITZ

Frank McCourt always felt that reading was 'like having jewels' in his mouth.

Little did he know, writing would put them in his pockets

Standing behind a podium before a large crowd of Jerusalem middle-school

children in Rehavia's Gymnasia school, Frank McCourt seems moderately

uncomfortable. It isn't the 60-odd years between him and the students that

disturbs him - nor is it a cultural dissonance.

"Is there any way I can sit down near the students," he gently asks. "I feel

like a politician standing up here."

In less than 10 seconds his microphone is shuffled forward, a chair appears out

of nowhere, and a glass of water is rushed to his side.

McCourt is accustomed to this celebrity treatment. Angela's Ashes, his 1996

memoir about his damp and miserable childhood in Ireland rocketed him from the

humble life of a retired public-school teacher to the pinnacle of literary fame;

his debut book has now been published in more than 30 languages and was quickly

adapted into a successful film.

Visiting Israel for the first time as a "cultural ambassador" sent via a State

Department program called CultureConnect, an entourage of embassy and consulate

representatives are his constant escorts.

McCourt is unfazed by their attentions, though. He is anxious to engage the

children, and once sitting in their midst, looks altogether at home.

Home for McCourt these days is New York, his birthplace and residence until the

age of four. From that point on, his life in the family's native country,

Ireland, would make their hardships in New York look petty. Due to the

tremendous success of his memoir, millions are now familiar with the years that

followed: besieged by hunger and penury, ever plagued by the cold and his

father's alcoholism.

The privations in Limerick in the Thirties and Forties were devastating.

Starvation was a way of life for many.

"When I look back on my childhood I wonder how I survived it at all," he writes

in the first lines of his memoir.

It would seem exaggerated if not for the bare facts of it. Three of his siblings

did not survive. Tuberculosis, pneumonia, and typhoid were rampant killers in

"the lane."

It is a tragic story, but not one McCourt thought anyone outside his family

would be interested in. So it came as a rather mind-blowing surprise when the

story struck a chord with people all over the world. When it hit the shelves,

Angela's Ashes jumped to the top of the New York Times bestseller list and

remained there for a staggering 117 weeks, selling more than four million copies

worldwide.

McCourt's first foray into writing rendered him a certified publishing

phenomenon.

His popularity was met with critical success as well, earning him numerous

accolades for his work, including the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book

Critics Circle Award. His second memoir Tis', was also catapulted onto the

bestseller list upon its release.

All this for

an unknown, retired schoolteacher.

DESPITE HIS accomplishments as a writer, it is clear McCourt remains a teacher

at heart. His eyes beam with enthusiasm when talking to children.

Upon meeting him, one is instantly charmed by the singsong cadence in his voice

which accompanies his indefatigable humor, a humor born of years of great

sadness and hardship. And there is nothing finer than watching this Irishman

warm to a story.

"When I was a child, Ireland was ridden by a disease called tuberculosis," he

explains to a small Jerusalem audience. "We called it consumption, or for a

serious case, galloping consumption. When I look at pictures from my childhood,

I see most of the boys in my class are gone, carried off by TB or alcoholism. So

many succumbed to the drink," he explains. "This fascinates me about Israelis.

People say, 'My God, what a place, there's no peace at all. Every day there's a

new conflict.' I think I'd have to drink three pints of Guinness a day."

McCourt jokes about drinking and about the situation in Israel, but takes

neither lightly. He took pains to avoid falling into the stereotype of the

drinking Irishman, but explains that in Limerick, it wasn't easy.

"I think the weather has a lot to do with the temperament of the Irish people.

Even when the sun is shining, it shines through the rain. George Bernard Shaw

talks about that, about the skies of Ireland and how they can drive you mad.

It's the reason pubs are so popular."

McCourt encountered quite different weather conditions during his stay in

Israel.

The warm atmosphere put him in a pleasant disposition, although his day was

predominantly spent being shuffled between various schools and lectures. Despite

the hectic schedule, McCourt took time to speak exclusively with the Post about

his past, his latest book, and the frenzy of success that accompanied his first.

He talks quickly but deliberately, as if in a whir of memory, associations

constantly fermenting.

"I'm fascinated with the levels of society here," McCourt says. "Everybody in

Israel has an interesting life because of the way you live every day.

"As a child, of course, I didn't see my own life as interesting. It was only

once my students began to ask me questions about my life, when they seemed to be

interested that I became convinced my life was worth recording.

"But I was always taking notes, notes about Ireland, about growing up.

I've been

keeping notebooks for 30 or 40 years now."

BIRTH OF A WRITER

When Frank McCourt talks about his writing, he does so with a certain nostalgia.

In a largely illiterate community, his love of reading and writing was formed at

a very young age.

In a climactic chapter of Angela's Ashes, Frank finds himself near death from

typhoid fever, spending several months in quarantine. There were perks, he

remembers: a hospital environment with steady meals, clean sheets, and best of

all, books. It was there that he was first introduced to Shakespeare.

"I don't know what it means and I don't care," he writes, "because it's

Shakespeare and it's like having jewels in my mouth when I say the words."

His love of language gave way to big dreams early on.

"I used to think that I'd like to write elegant prose, piling clauses on top of

clauses, and it would go on for a page and a half until you had no idea what you

were talking about. I soon discovered the value of simplicity and clarity."

Part of the appeal of your books is that spare, direct narrative. How did you

come to write so honestly about yourself?

It wasn't a 'process.' It had to do with the experience of working with a bunch

of kids. With them you have to be very clear and explicit about what you're

saying. They're not good with generalization or ambiguity. You have to get to

the point and keep the energy going.

That's the appeal of this program [CultureConnect] to me. To stir the kids up a

bit.

You mentioned that you had rare access to books as a child.

In the beginning there were no books. They eventually established the Carnegie

library. But I was always reading. Anything.

Books would sometimes come into the lane. I remember finding out that somebody

had a copy of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. And that was passed from

family to family practically. It eventually came to me; I read it and then

passed it to my brother. Books were as rare as diamonds. There were comic books,

though, and there were newspapers. You just read everything. One couldn't be

discriminating in Limerick. If it was printed, you read it.

Was Mark Twain then one of your biggest influences?

It was like the first experience of sex. I loved Dickens too. There was always

Dickens. Oliver Twist, and English boys books. People would bring them back from

England, books of growing up in English boarding schools. Far removed from our

experience. And English detective novels [McCourt speaks now in a stream of

memory]. Agatha Christie too... that was what interested me... but then again,

maybe that's because it was all we had. The thing is, there was nothing else. We

had no television, no radio.

As you were writing your memoirs, were you surprised by the depth of detail in

your memory?

There was a columnist in the New York Times once, Anna Quindlen, [who wrote a

book about her life]. I don't understand how she remembered such details of her

life when she was just 14. But when your life is uncluttered, when its bare and

you have nothing, you remember the things you have.

So you felt confident writing from a child's point of view.

I was comfortable writing in the present tense. In a child's voice. People ask

why I don't use punctuation. Well, children don't use punctuation, and I'm not

particularly good with it anyway. I am very good with periods. I'm weak with

commas and useless with colons and semi-colons. I think I found a colon in the

book the other day. It was not my doing. It must have been the publisher.

You must have taken some liberties with your writing and memories - dialogue,

for instance.

Yes - but not really. There's something liturgical with the Irish language, with

the way people greet each other and talk. All I had to do was recreate what

actually happened.

A TEACHER'S EVOLUTION

Although he never attended high school, McCourt was well-read and persuaded an

admission officer at NYU to admit him, using the GI bill to pay for tuition and

working nights doing manual labor. After graduating, he began to teach in the

public school system.

He recalls his emigration experience in his second bestselling memoir Tis'.

"To arrive here was like emerging from an Irish womb," McCourt said in a 1998

Reader's Digest interview. "I might have had the English language, but I was

unequipped: no education, no self-esteem; I was not a very fine specimen."

Teaching would be a salvation of sorts for McCourt, triggering memories of his

own childhood for the notebooks he kept.

"I'd write on the right page," he explained, "and on the left I'd leave space

for notes and thoughts for future masterpieces. So I started writing about my

mother and father."

In the back of your mind did you ever think your notebooks would evolve into a

book?

I used to think I'd like to write plays, like my favorite writer Sean O'Casey.

But I didn't. I started teaching, and there's no time to write when you're

teaching. None when you're a high school teacher. It's easier to be a reporter

at The Jerusalem Post. You can do your job and then go on and write a book if

you like. Your head is filled. I mean, can you imagine having kids like this

[referring to the mildly rowdy Gymnasia students] all day long? Five days a

week. You'd have to be a saint. But maybe I've developed sainthood, I don't

know.

Do you miss teaching?

Yes, but it's very hard though, to do it all day long. When you get home, the

first thing you do is throw yourself on the floor, and your head is ringing with

all these voices. It's better to be a university professor. Scholarship is

easier, that's pleasurable. You go home and read. You don't have to assume all

the roles that a high-school teacher or elementary-school teacher does. With

kids, you have to be a disciplinarian, a scholar, a priest, a rabbi, a counselor.

When I look back though, I have to give myself some credit for surviving and

perhaps prospering, because I learned something about writing during those

years. I learned something about myself and the human heart. In Ireland, the

only introspection we were allowed was a day before confession, to examine your

con-science and find what sins you've commit-ted. A good exercise for writers,

actually. Writers are usually full of sin, otherwise they'd have nothing to

write about.

What does the new book you're writing focus on?

It's about teaching. The new book will pick up where Tis' ended off. In this

book I want to get into the craft of teaching, show what it's like in the class

room day after day after day. There's a rhythm in the school year, a texture.

There's a chemistry you form with your students. You can smell when they're

drifting away from you and how to bring them back. You're like a sheep dog in a

way. You know when you're losing their attention and sometimes you don't know

what to do. Then you get angry and you yell at them and you lose it completely.

The only subject that will get everyone's attention is sex.

A STAR IS BORN

WHEN ANGELA'S Ashes was turned into a Hollywood film, Frank McCourt's fame

jumped from enormous to overwhelming. Only one other movie had a bigger opening

in Ireland than Angela's Ashes, and that was Titanic. For a small-town boy from

Limerick, it was a thrill and terror all at once.

One of the children in the audience mentioned The Lord of the Rings as his

favorite book. You replied that watching the movie before reading the book could

kill it. Do you think watching the film of Angela's Ashes before reading it

could kill the experience?

I think it might. People would say it was dreary, humorless.

Alan Parker, the director, said he wanted to be faithful to the book, and he

was. Too faithful - to the wrong parts of the book.

There are other moments in the book that are a little lighter.

How much involvement did you have with the script?

I had nothing. Nothing (he says this adamantly, as if to avoid any

responsibility for it).

I think if I'd done it... well, let's just say they didn't ask me to write the

screenplay.

Did you walk away with a feeling of disappointment?

A bit, yes, a bit. Well, [he says, backtracking], I think it was an honorable,

an honest effort. But it didn't capture the craziness. That's what I was after.

The craziness of poverty. People are made mad by it. Because every day you're

hanging on. Your mother has to go out and beg and get a loaf of bread somewhere.

You have to find ways of amusing yourself. And most of all you're dreaming...

dreaming of the day your belly will be filled, when you'll have clothes, shoes.

Were you aware of your poverty in relative terms as a child?

Beyond the streets that we lived in we saw people were comfortable. We saw

people in houses and we'd pass them and smell bacon frying in the morning; you'd

see other kids well-dressed and riding new bicycles. You'd see all of that, but

you didn't have the intellect yet to say 'what's going on here?' Which is what I

was trying to get across to the kids [in the Gymnasia]. There's another world

out there.

I did have one moment of celebrity when I was 11 years old. I got typhoid and

went to the hospital. And the day I left, after three and a half months in the

hospital, I went home and people were hanging out their doors, waving at me and

cheering me, because I survived the typhoid. I almost died, and suddenly I felt

people noticed me.

How did the celebrity of a big blockbuster book compare?

It hit me very hard. I didn't understand it.

My wife always had faith, and my editor did, too. I didn't believe them though.

I thought, 'every week thousands of books are published.' I didn't say to

myself, there must be something about this book that will get it noticed in the

New York Times. Not that I'm excessively modest, but I said to myself, "why do

people like it?"

It was like a wave that rolled over me. It was on television, I was in

interviews, and the radio. And I was paralyzed by all of it. It started to

happen very fast and continued into the making of the movie. Then I wrote the

second book and it showed up on the bestseller list.

It was surreal.

You must be exhausted from talking about it.

I remember once, in Sydney, I had interviews from six in the morning until six

at night. Afterward, I went back to the bedroom where Ellen [my wife] was

waiting for me. I had spent the whole day talking, and she was lying on this big

acre of a bed, and I said to her, "I'm coming over to your side to get away from

myself."

RELEASING THE PAST

ONE OF the foremost themes in Angela's Ashes is religion; often a source of

guilt and fear, but also an inextricable part of McCourt's identity. The

influence of the Church in Ireland is something that McCourt says one couldn't

possibly understand unless they had experienced it.

"When we were born, we learned that we were created in sin. This is the fear

that I lived with - that if one day I were hit by a truck or run over by a

subway train I was going to hell for all my mortal sins. I wrestled with this

all the time."

Do you still consider yourself a Catholic?

No - well, actually, it's like the Mafia, once you're in you're in. The only way

out is in the coffin. But I'm fascinated by what it did to me, or what it did

for me. And what a powerful and extremely ingenious institution it is.

What's your reaction to what's going on in the Church today?

We knew that all along. Anyone who was a kid growing up in Ireland knew this was

happening. But you didn't open up your mouth about it. You didn't even mention

it to your friends.

There was a priest who came onto me once when I was a kid. He was supposed to

encourage us to go away and join an organization called The White Father - but

that was his gimmick. He was supposed to be recruiting boys.

And he tried. He told me once he wanted to give me a physical examination. I'm

sure I was ready for having it [he says raising his eyebrow with sarcasm]. I

said, 'I don't think so.'

But nobody knows what the priests were doing overseas, in Africa and India and

the Philippines. They got away with it because nobody reported them. And now

they're all acting 'oh, surprise.' What they hell did they think they were doing

all these years? Certainly not being celibate.

Were your memoirs a final confession of sorts?

No. There is no end to it. My concern now is the stuff that's foisted on kids

all over the world by various religions and how people are indoctrinated and

brainwashed and bullied.

Have you let go of all the guilt associated with being Catholic?

Yes I have.

My relationship with Ireland is such that now I can look at in a fairly

comfortable way. In the beginning I felt a hostility. I'd see a schoolmaster and

I'd want to punch him in the nose, but the years passed, and they looked old and

weak. I feel a sense of ease now. The country moves me.

The long struggle against the English led to so much literature, poetry, and

plays. And I keep saying that I'm so glad the English invaded us and beat the

shit out of us, because they helped us produce this body of literature - Yeats,

and Seamus Heaney, Sean O'Casey and James Joyce. So I can go back now on my own

terms. I can go to Limerick and look at every shop, every brick lane, every

church, and everything has a different memory for me.

And that's a

rich experience.

McCourt's recycled school days

Memoir about

teaching relies on too-familiar tales

By Brendan Halpin

|

November 20, 2005

Teacher Man

By Frank McCourt

Scribner,

258 pp., $26

Crafting a good

memoir is every bit as much work as crafting a novel. It is an act of creation

to cull a compelling story out of the chaos of existence. If this work is not

done well, the result is not an involving story, but a shapeless, rambling mess

of self-aggrandizing anecdotes.

Despite Frank

McCourt's previous triumphs crafting memoirs, his ''Teacher Man" begins

inauspiciously. In Chapter 1, after summarizing his first two days on the job as

a high school teacher, McCourt announces: ''Otherwise, there was nothing

remarkable about my thirty years in the high school classrooms of New York

City." The reader may feel a certain amount of trepidation about what will fill

the remaining pages if this is the case.

Such fears

initially seem groundless. McCourt describes the disconnect between his training

and the reality of teaching as well as anyone ever has -- ''Professors of

education at New York University never lectured on how to handle flying-sandwich

situations" -- and his account of his first two days of teaching sings.

But, after the

first two days, we reach the ''unremarkable" part of McCourt's career, and

''Teacher Man" goes into a death spiral of tedium. Faced with tough students he

doesn't know how to teach, McCourt begins telling them and his readers stories

from his childhood. Alas, McCourt has already poured his best childhood material

into ''Angela's Ashes," so here, he serves up the dregs: He actually includes a

lengthy passage recounting the day his mother bought him a suitcase.

The rest of the

memoir continues in this fashion, with scenes from McCourt's teaching

interspersed with increasingly ill-chosen, tangentially related anecdotes from

his life outside the classroom. What results is a book that fails as both an

account of McCourt's teaching and of his life. This is, in large part, because

the McCourt depicted in ''Teacher Man" is something of a cipher. The bulk of the

anecdotes here are presented with a minimum of reflection or introspection.

Indeed, McCourt, the author of three memoirs, includes this rather curious

admission: ''There is an activity called 'pulling yourself together.' I tried,

but what was there to pull together?" If McCourt has no self, whom exactly is he

writing about?

McCourt

acknowledges being forced into therapy by his wife, but he doesn't say why he

might have needed it, and his sneering account of his group therapy serves only

to show his contempt for the other participants. McCourt also recounts an

extramarital liaison without explanation. Indeed, he recounts a number of his

sexual adventures to no apparent purpose, culminating in a repugnant episode

involving a woman he sleeps with despite his hatred for her personality and his

disgust at her ''vast, blubbery body." What are we to make of this?

McCourt's

stinginess with his thoughts and feelings about his personal life would sit

easier if he were a more generous narrator of his teaching career. But here,

again, he simply reports events without much commentary. He acts violently

against students twice but doesn't stop to tell us whether he feels contrite,

whether he thinks these incidents have any bearing on his fitness to teach, or

how it feels to act on a teacher's darkest fantasy. When writing about his early

career McCourt seems scornful of students, parents, administrators, and his

younger self; indeed, his recollections of his first few years of teaching are

so sour that they provoke the question of why he kept teaching at all, but this

question apparently doesn't interest him.

Of course the

author and readers of a memoir may be interested in different facets of the

story, but ''Teacher Man" is such a hodgepodge that it's impossible to discern

which facets of the story interest McCourt himself.

For some readers,

his skill as a prose stylist may be enough to carry ''Teacher Man." He has an

undeniable gift for turning a phrase, as in this passage about his post-divorce

life: ''I could never tell them how . . . every night I struggled to drown out

the sounds of rowdy sailors off freighters and container ships, how I stuffed

cotton wool in my ears to muffle the shrieking and laughing of women . . . how

the pounding of the juke box in the bar below . . . jolted me nightly in my

bed."

Yet as ''Teacher

Man" drags on, McCourt's style starts to feel predictable. The inexplicable

forays into second-person narration, the Irishisms, the flights of fancy -- we

have been here before, and now these seem not innovative storytelling

techniques, but gimmicks.

Though only half

of ''Teacher Man" is about teaching, McCourt still manages to succumb to the

pitfalls that plague most teaching memoirs: He complains about low pay,

disrespect, and the idiocy of the administrators, and he renders the students as

two-dimensional types in cute dialect. Finally, at the end of the book, McCourt

sinks to the most contemptible convention of such memoirs: poaching the

interesting or tragic life stories of the students to make the teacher seem more

interesting and heroic.

After two wildly

successful memoirs, many readers will buy ''Teacher Man" on the strength of

McCourt's name. Those looking for an involving story will be disappointed, as

will those hoping for a fresh look at teaching. Even those interested in McCourt

as a person will find reading this odd, cranky book a frustrating experience.

Brendan Halpin is the author of the novels ''Donorboy" and

the forthcoming ''Long Way Back," as well as two memoirs, including one about

teaching.

December 4, 2005

'Teacher Man: A Memoir,' by Frank McCourt

The Stuyvesant Test

Review by BEN YAGODA

IT was by no means a done deal that you

would be reading these words. To review "Teacher Man," I had to read "Teacher

Man," and to read "Teacher Man," I had to get my hands on it. This proved

challenging because no sooner had the advance copy entered the house than my

teenage daughter snatched it and repaired to her room. I thought I had a chance

when she was done, but my wife beat me to the punch. I was standing in wait when

she turned the last page, and I grabbed the book. My mother-in-law, visiting

from out of state, had her eye on it, I knew, but my glare told her she'd have

to pry it from my cold, icy hands.

Yes, Frank McCourt, the author of

"Angela's Ashes" and " 'Tis," has done it again - distilled from the mash of his

life a strong and alluring narrative brew. You start reading, one story leads to

the next, and all of a sudden two hours have passed. The wonder is that an

entire household would have picked up on that from a set of galley proofs bound

in plain blue paper.

"Teacher Man" has less heft than its

predecessors in a couple of senses of the word: it is less packed with incident,

passion and regret, and it's shorter. But it complements them. More than that:

it completes them, with a strong, satisfying and - could it be? - happy ending.

Animating the earlier books was a paradoxical tension. These were narratives of

the absolutely highest level, richly textured and unputdownable. Yet McCourt

depicted himself as tongue-tied and shy and capable of thinking up good

comebacks only on the way down the stairs following his many painful encounters.

Where did that fellow turn into the great yarn spinner, the Pulitzer Prize

winner who stands atop best-seller lists, arms akimbo?

As it turns out, in the classroom. In

1958, 27 years old and a recent graduate of New York University, courtesy of the

G.I. Bill, McCourt took a job as an English teacher at McKee Vocational and

Technical High School on Staten Island. On his first day, at the start of his

first class, one youth hurled a sandwich at another. All McCourt could think to

say was, "Stop throwing sandwiches." A third youth replied (and McCourt's

rendition of the patois of New York teenagers is priceless): "Hey, teach, he

awredy threw the sangwidge. No use tellin' him now don't throw the sangwidge.

They's the sangwidge there on the floor." McCourt writes:

"The sandwich, in wax paper, lay halfway

out of the bag and the aroma told me there was more to this than baloney. I

picked it up and slid it from its wrapping. It was not any ordinary sandwich

where meat is slapped between slices of tasteless white American bread. This

bread was dark and thick, baked by an Italian mother in Brooklyn, bread firm

enough to hold slices of a rich baloney, layered with slices of tomato, onions

and peppers, drizzled with olive oil and charged with a tongue-dazzling relish.

"I ate the sandwich."

The episode was emblematic of his life as

a teacher, which would last another 30 years. Admittedly ill equipped for

administering the conventional high school curriculum, McCourt conducted his

classes with panic-born stealth and cunning: sometimes eating a sandwich,

sometimes moderating oddball dialectics, sometimes singing Irish folk songs,

sometimes studying the narrative strategy of recipes, nursery rhymes and excuse

notes, but most often just telling stories. "My life saved my life," he writes.

He recognized from the start that this played into the hands of shrewd classroom

veterans who knew you could always avoid the lesson plan by getting the teacher

up and rocking on a hobbyhorse. But that didn't matter. He perceived that the

best way for his students to learn something was for him to learn something, and

the best way to achieve that was to interpret and share his life and hard times.

Not that he handed them rehearsed and well-worn yarns; those are dull and

unsurprising to speaker and listener alike. No, he told the kind of stories

whose paths and endings are a revelation.

McCOURT ended up teaching creative writing

at Stuyvesant High School in Manhattan. There his classroom style merged with a

conception of writing that was less about putting words on paper than about

active observing and imagining: "Every moment of your life, you're writing. Even

in your dreams you're writing. When you walk the halls in this school you meet

various people and you write furiously in your head. . . . You see someone you

like and you say, Hi, in a warm melting way, a Hi that conjures up splash of

oars, soaring violins, eyes shining in the moonlight. There are so many ways of

saying Hi. Hiss it, trill it, bark it, sing it, bellow it, laugh it, cough it. A

simple stroll in the hallway calls for paragraphs, sentences in your head."

McCourt retired from Stuyvesant in the

late 80's, in part because of a nagging rhetorical question: "Who was I to talk

about writing when I had never written a book never mind published one?" His

one, two and now three masterly memoirs show that he learned his own lessons

well. "Teacher Man" is an irresistible valedictory, about a man finding his

voice in the classroom, on the page and in his soul.

Ben Yagoda is the author, most recently,

of "The Sound on the Page: Style and Voice in Writing." He has just finished a

book on the parts of speech.

Frank McCourt learns as much as he teaches in America

Reviewed by Floyd

Skloot

Sunday, December

11, 2005

Teacher Man

A Memoir

By Frank McCourt

SCRIBNER; 258 Pages; $26

Frank McCourt published his first book, "Angela's Ashes," at the age of 66.

A memoir embedded in the poverty and misery of his distant Irish childhood, it

had a carefully controlled voice, that of a naive and baffled little boy from

the Limerick slums. Its characters and setting were vividly realized, its

language fresh and its mix of humor and sadness deftly balanced.

"Angela's Ashes" was a best-seller, won the 1997 Pulitzer Prize and was followed

in 1999 by " 'Tis." This sequel carried McCourt's story forward from the point

of his arrival in America as a teenager, culminating with the start of his

career as a New York City high school teacher. Though no longer a child's, the

narrator's voice in " 'Tis" remained naive and baffled as McCourt experienced

himself still an outsider, the immigrant and novice teacher with a brogue,

buffeted by a world he could neither control nor comprehend. Funny and touching,

it left a reader wondering what happened in the ensuing three decades of

McCourt's life. How did this Irishman who never felt he belonged anywhere get

from being an American high school English teacher in his early 30s to an

acclaimed debut writer in his late 60s?

"Teacher Man," the third in McCourt's series of memoirs, is meant to tell us

that. It traces his career at four New York City public high schools and a

community college, flashes back to material covered in his previous memoirs,

pauses occasionally to offer reflections on pedagogy and American teenage

behavior and briefly covers his aimless doctoral studies during a return to

Ireland. But the writing lacks McCourt's familiar energy and control of tone,

immediacy of scene, outrageous humor, richness of character and setting.

"Teacher Man" seems listless, forced, as his previous two memoirs never did, its

sporadic moments of passionate brilliance only reminding the reader of how

disengaged the rest of the book seems. It is difficult to imagine Frank McCourt

writing something as flat and didactic as this statement of classroom insight:

"Kids want to be cool. Never mind what parents say, or adults in general. Kids

want to hang out and talk street language."

McCourt presents himself once again as naive and baffled. An outsider. "If there

was a circle I was never part of it. I prowled the periphery." But the act wears

thin when he is speaking of himself as a grown man, a teacher meant to impart

knowledge and clarity to young students typically presented as wiser and more

worldly than he is. McCourt seems to realize this, and no longer relies upon the

innocent's voice and tone that carried his earlier books. Instead, "Teacher Man"

speaks in a knowing, avuncular manner, summarizing rather than creating scenes,

relying upon ironic commentary or one-sentence paragraphs, like notes for a

lecture:

"Instead of teaching, I told stories.

Anything to keep them quiet and in their seats.

They thought I was teaching.

I thought I was teaching.

I was learning.

And you called yourself a teacher?"

Inner-city classrooms, the machinations of educational bureaucracy and rigid

curricula are all alien to McCourt. They remind him of his church-dominated

childhood; the strange byways of the midcentury Manhattan, where he landed as an

immigrant; the military in which he served. There is an unaccustomed note of

self-congratulation as he writes about how he succeeded despite them:

"I learned through trial and error and paid a price for it. I had to find my own

way of being a man and a teacher and that is what I struggled with for thirty

years in and out of the classrooms of New York. My students didn't know there

was a man up there escaping a cocoon of Irish history and Catholicism, leaving

bits of that cocoon everywhere."

Much of "Teacher Man" consists of anecdotes about students and colleagues. They

are seldom presented as fully developed characters, however, but as figures used

to illustrate his idiosyncratic approach to teaching, which relies upon

autobiographical storytelling, as though 30 years of experience in the classroom

were, in essence, rehearsal for McCourt's memoir writing.

There are scattered passages that suggest the sort of ingenious teacher and

engaging writer McCourt has been. In one, he uses students' obviously forged

parental notes of excuse as the basis for a lesson in imaginative writing. In

another, he treats cookbooks as literature and stimulates his multiethnic

classroom to share their traditional foods.

"When I talk to those kids I'm talking to myself," he writes near the book's

end. "What we have in common is urgency." But despite his insistence, "Teacher

Man" seldom evokes urgency on the part of McCourt or his students. It settles

for something that McCourt clearly never settled for as a teacher, and never

settled for as a memoirist before: the safety of disengagement.

Floyd Skloot received the 2004 PEN Center USA Literary Award in Creative

Nonfiction for his memoir "In the Shadow of Memory." The follow-up, "A World of

Light," was published in September.

Teaching as

triumph

(Filed:

18/12/2005)

Francis Gilbert reviews Teacher Man

by Frank McCourt.

It is impossible to read Frank McCourt's new memoir, Teacher Man, about

his life as a teacher in New York, without the incessant rain of Ireland

drizzling into one's thoughts.

McCourt's first book, Angela's Ashes, published when he was 66, won the Pulitzer

Prize, has sold millions of copies throughout the world, was turned into a

successful Hollywood movie, and has astonished and moved anyone who has read it.

In it, McCourt writes in the most luminous prose about his poverty-stricken but

bizarrely inspiring childhood in Ireland. His mother, Angela, brought up the

family while enduring the vicissitudes of a drunken husband, the deaths of three

children, and the barbarous edicts of a repressive Catholic church. At one

point, she was reduced to begging for food and clothing.

McCourt survived these horrors and emigrated to New York where he scraped a

living doing menial jobs. Later, he was drafted into the United States Army: a

story which he tells in the engaging but less magical sequel, Tis.

His escape from such a terrible upbringing and numerous hardships as a young

man, means that when he takes a solid teaching job in this new book, the reader

feels that it is a remarkable triumph. This is why this memoir about teaching is

unlike any other I have read: relatively mundane events and incidents shine

against the backdrop of that pathetic, abused child.

In Teacher Man, McCourt recounts the story of his travails and triumphs during

four decades of teaching in the New York public school system. He taught

teenagers and adults in four high schools: two working-class schools and two

more middle-class ones. He estimates that in all he taught 12,000 pupils. Being

imaginative, sensitive and well-read, he struggled with the robotic authorities

and irate parents who suggested at various points in his career that he should

find another job.

As a teacher in the British system, I was fascinated to learn that during the

1950s and 1960s the American education boards, for all their backward thinking,

put motivating the students at the heart of the curriculum; an injunction which

is sadly lacking in most of the school policy documents which are issued in

Britain today. It was this imperative which forced McCourt to come up with some

of his most innovative ideas, such as getting the pupils to write a suicide note

in response to a depressing poem, cooking their own food to improve their

vocabularies, chanting recipes and obscene nursery rhymes to stimulate their

imaginations, and relating many of the set texts to their own lives so that they

could see literature's true significance.

The high point of McCourt's teaching career was his time at Stuyvesant High

School, perhaps the most respected state-run school in New York. Here he

flourished because he was allowed by the enlightened authorities to teach what

he wanted.

There is nothing hugely original about the stories that McCourt tells here. If

you had not read Angela's Ashes and Tis then Teacher Man would be unexceptional.

But if you have, then the book is transformed.

July 20, 2009

Frank

McCourt, the teacher

By Kevin Cullen, Globe

Columnist

Read this article,

here