16-4-2002

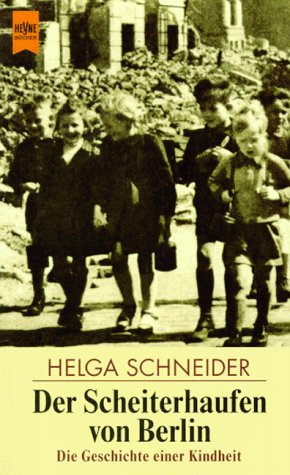

HELGA

SCHNEIDER

Helga Schneider,

“Lasciami andare, madre”, Adelphi, 2001, pp.130 (*)

Site:

http://www.helgaschneider.com/

(*) Março de 2003:

Tradução publicada em Portugal pela

Difel com o título "Mãe,

deixa-me ir embora"

| |

LE

MONDE | 15.03.02 | 11h42

•

MIS A JOUR LE 15.03.02 | 12h58

Helga Schneider,

fille de SS

A 34 ans, Helga Schneider retrouve sa mère et découvre qu'elle l'avait

abandonnée, enfant, pour devenir kapo à Auschwitz. A 65 ans, elle raconte,

enfin. |

|

|

Helga

Schneider dans une rue de Bologne (Italie),en 2000 | Cendamo / Grazia

Neri |

|

Elle a une tête banale, bien sûr, la mère d'Helga Schneider. Rien, sur son

visage, ne laisse deviner que cette vieille dame aux cheveux blancs, si menue,

si fragile, qui sourit gauchement devant la caméra, a été, dans les années 1930

et 1940, à Berlin, une militante nazie, membre de la Waffen-SS. Rien, quand on

la voit, ne laisse soupçonner que cette frêle créature, aux épaules légèrement

voûtées, a été gardienne dans les camps de la mort de Ravensbrück et d'Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Ni qu'elle a été condamnée, en 1946, par le tribunal de Nuremberg.

Rien ne la trahit, sinon, peut-être, ses mâchoires qui se mettent à trembler,

quand une question la trouble. "Les mâchoires ! Les mâchoires !", répète

sa fille Helga, en pointant du doigt l'écran télévisé, comme si ce tremblement

sénile constituait un aveu. Le reportage de la RAI, dont Helga Schneider garde

précieusement la cassette, date de 1998. C'était la deuxième fois, depuis 1941,

que la fille revoyait sa mère. Dans le film, on la découvre, elle aussi, dans

cet hospice des faubourgs de Vienne, en Autriche, où l'équipe de la télévision

italienne a retrouvé la trace de l'ex-kapo du IIIe Reich. La vieille

femme n'a pas de remords. Gros plan sur son visage. Ce qui fait trembler ses

mâchoires, c'est plutôt une sorte de colère. D'ailleurs, tiens, elle le dit,

elle le crache : oui, elle a été Waffen-SS. Et alors ? Le monstre aux cheveux

blancs sourit. Helga Schneider, elle, a les larmes aux yeux. Elle arrête

brusquement la cassette.

Assise dans le salon-bureau de son petit appartement de Bologne, dans le nord de

l'Italie, celle que le quotidien turinois La Stampa a baptisée la

"fille d'un cauchemar" tente de se rappeler où elle a bien pu mettre les

photos de sa mère. Au total, elle n'en possède que trois. Dont deux qu'elle

avait prises elle-même, en 1971, lors de leurs premières retrouvailles. L'idée

qu'elle puisse ressembler à celle qui l'a mise au monde, cette idée la

"hante" et la "foudroie". Pense-t-elle que l'abjection peut se

transmettre par les gènes, comme ses cheveux blonds et ses yeux bleus, hérités

de sa mère — dont elle est, frémit-elle, "le portrait tout craché" ?

Est-ce pour cela qu'Helga Schneider, aujourd'hui âgée de 65 ans, a mis si

longtemps — plus de trente ans : une vie ! — à refaire le chemin vers l'enfance,

vers Berlin, vers cette mère enfin, cette mère sans nom, qui avait quitté son

mari et ses deux jeunes enfants, en 1941, sans plus jamais faire signe, cette

"mutti" impossible, cette chose imprononçable, qu'elle a d'abord, "par

naïveté", essayé de haïr ? Dans le livre qu'elle lui a consacré, Helga

Schneider ne répond pas. Ecrit en italien, sa langue d'adoption, Laisse-moi

partir, mère a d'abord été publié à Milan par Adelphi, en 2001, avant d'être

traduit en français, ce printemps, par Robert Laffont. C'est un puzzle, dont

"plein de morceaux manquent", admet l'auteur. Un manteau d'Arlequin, fait de

trous et d'énigmes. Jusqu'à l'âge de 34 ans, Helga Schneider ne sait rien de sa

mère, sinon qu'elle est née à Vienne et qu'elle a quitté, en pleine guerre, le

foyer familial. "Je n'ai appris le nom de ma mère — son nom de jeune fille —

qu'en 1971, grâce à un ami à moi qui a réussi à retrouver, sur les registres

d'état civil, à Vienne, les coordonnées de cinq femmes divorcées, ex-Schneider.

J'ai écrit à ces cinq femmes. L'une d'elles m'a répondu : c'était ma mère. Mais

de son enfance, je ne sais rien, sinon qu'elle avait trois sœurs. Et j'ignore

quelle a été sa vie entre 1949 et 1971, entre le moment où elle est sortie de

prison et celui où je suis allée la voir à Vienne, pour la première fois, avec

mon fils Renzo."

Il y a les choses qu'Helga Schneider ne sait pas. Et puis il y a les choses

qu'elle sait, mais qu'elle n'a pas mises dans son livre. Et celles, aussi, qui

restent en elle, comme suspendues, flottantes, qu'elle ne veut ou ne peut pas

dire. Qui lui échappent, parfois. Comme les insultes de la grand-mère

paternelle, qui n'aimait pas Hitler et détestait sa bru, la traitant de

"putain nazie". Les mots violents, les injures, les jugements à

l'emporte-pièce, Helga Schneider s'en méfie. A propos de cette scène du livre,

inouïe, au cours de laquelle l'ancienne kapo d'Auschwitz veut offrir en

"cadeau" à sa fille (parce que "cela pourrait [lui]

servir en cas de besoin")

une poignée de bijoux en or, volés aux déportés, Helga Schneider se

refuse à qualifier le comportement de sa mère — qui lui répugne au plus haut

point — de monstrueux : "Cela n'était ni monstrueux, ni affectueux. Son geste

était inhumain, égoïste et aussi ingénu : comment penser qu'on peut 'racheter'

sa fille avec de l'or, avec cet or ?"

A priori, l'histoire d'Helga Schneider n'a rien d'exceptionnel : des centaines

de milliers d'"enfants

d'Hitler", pour reprendre le titre de l'enquête de Gérald L. Posner (Albin

Michel, 1993), ont vécu un drame similaire. Certains d'entre eux, comme Niklas

Frank, dont le récit autobiographique a été publié en Allemagne (Der Vater :

eine Abrechnung, Münich, Bertelsmann, 1987) puis aux Etats-Unis (In the

Shadow of the Reich, New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1993), en ont témoigné

publiquement. Parmi ces voix, rares sont pourtant les voix de femmes. Plus rares

encore sont les foyers allemands où les épouses "portaient la culotte" (et

l'uniforme) des nazis. C'est ailleurs, cependant, que réside l'originalité de

l'auteur de Laisse-moi partir, mère. Ce livre, en effet, n'est pas le

premier récit autobiographique qu'Helga Schneider a publié. Il est le fruit le

plus récent d'un lent et extraordinaire autodévoilement de la mémoire par

l'écriture.

S'étant fixée "un peu par hasard" à Bologne, au début des années 1960,

après des années difficiles en Autriche, la jeune Berlinoise, qui a appris

l'italien en quelques mois, tâte d'abord du journalisme. Elle rédige des

interviews pour les quotidiens nationaux et passe le reste de son temps à écrire

pour elle-même, au grand dam de son mari, Elio, restaurateur de son état, et

qui, quoique "très gentil et très brave", la préférerait dans un rôle de

"mamma" plus traditionnel. Mais Helga n'en fait qu'à sa tête. "J'ai

toujours rêvé d'être une romancière", dit-elle, avec ce mélange de candeur,

de narcissisme et d'énergie qui l'a sans doute aidée à ne pas perdre pied. Ce

qu'elle écrit alors n'a rien à voir avec la politique et le nazisme. Quand elle

a quitté Berlin, en 1948, à l'âge de sept ans et demi, elle était une enfant

blessée, révoltée par la dureté du monde : "Je voyais l'Allemagne comme le

pays qui m'avait fait du mal. Je détestais la planète entière", se

souvient-elle. A Salzburg et à Vienne, en Autriche, où elle passe son

adolescence et étudie la littérature et les beaux-arts, la "jeune femme en

colère", comme elle se définit elle-même, ne s'intéresse pas aux procès des

dignitaires nazis qui défrayent la chronique. La politique l'ennuie, elle ne

vote pas. Elle adore les romans d'amour. Elle est pauvre et essaie de survivre.

Brouillée avec ce qui lui reste de famille, elle se réfugie dans les livres,

dévorant pêle-mêle Dostoïevski et Karl May, Ibsen, Schiller, Goethe et Kafka. Sa

mère ? "Je n'y pensais jamais."

Ce n'est qu'en 1966, à Bologne, à la naissance de son fils Renzo, qu'Helga

Schneider "commence à ressentir un manque. Un manque de mère". Quand son

petit garçon atteint l'âge de quatre ans - l'âge qu'elle avait elle-même quand

sa mère est partie -, elle entame les premières recherches, via ce fameux ami

viennois, à qui elle demande de consulter les registres d'état civil. "Comme

mon père n'avait jamais rien dit, j'ai cru longtemps que ma mère était partie

pour rejoindre un autre homme. J'étais prête à tout pardonner." La première

rencontre, en 1971, dans le petit appartement de Vienne où vit à l'époque la

mère d'Helga Schneider, est un terrible choc. La sexagénaire qui lui ouvre la

porte n'est pas une repentie. Elle ne regrette en rien d'avoir abandonné ses

enfants. Et moins encore d'avoir porté l'uniforme SS, qu'elle garde dans son

armoire, comme une relique. D'elle-même, elle raconte à sa fille comment elle a

été arrêtée, à Auschwitz, au moment de la libération du camp. "Elle m'a

dit : - Après la mort du Führer, je me suis sentie anéantie. Parce que le

nazisme, c'était la vie ! — Wieso denn ? — Das was doch so schön !" [Comment

cela ? — C'était pourtant si beau !] Je

me rappelle encore ses mots", dit Helga Schneider d'une voix sans

timbre. Le petit garçon écoute les deux femmes, sans comprendre. Bouleversée,

Helga Schneider s'enfuit avec son fils et ils reprennent aussitôt le chemin de

Bologne. Elio, le mari, ne saura rien de ce séisme.

La vie reprend son cours, comme si de rien n'était : "J'avais décidé

d'oublier cette première onde, je voulais oublier ma mère", explique Helga

Schneider. Seul changement : elle se met à lire, en italien, des livres

d'histoire ; elle découvre l'invasion de la Pologne, le front russe. Elle

reprend ses travaux d'écriture, emplissant ses tiroirs de romans jamais publiés.

Depuis la mort de son mari, décédé en 1985, elle a de plus en plus de mal à

joindre les deux bouts.

"Ce qui a fait déclic, ce n'est pas cette rencontre avec ma mère, mais

l'interview avec le journaliste de

La Stampa Gabriele Romagnoli.

C'était en 1994. Mon premier roman, La Bambola decapitata, venait de sortir

et il devait écrire quelques lignes. Il m'a téléphoné de Turin : il voulait

savoir qui j'étais, connaître un peu ma vie — juste pour compléter son article.

Et, je ne sais pas pourquoi, tout est sorti d'un coup : Berlin, ma mère, la

Waffen-SS... C'était la première personne à qui je racontais ma vie." Le

journaliste, évidemment, laisse tomber le roman — "pas terrible, de toute

façon", estime Helga Schneider - et noircit une page entière sur l'histoire

de la petite Berlinoise, enfant du "cauchemar" nazi. C'est lui,

précise-t-elle, qui la pousse à abandonner la fiction et à écrire sur sa vie.

Elle rédige "en quatre mois" son premier récit autobiographique, où elle

raconte ses souvenirs d'enfant, plongée dans la guerre et le totalitarisme nazi.

Ce récit, Il Rogo di Berlino, paraît en 1995, aux éditions Adelphi. Il

sera réédité quelques mois plus tard, en collection scolaire. Pour Helga

Schneider, ce succès est comme une "explosion". Une nouvelle vie

commence : "Avec Il Rogo, le monde

m'a acclamée. J'étais un cas littéraire !" s'enthousiasme-t-elle.

Suivront deux autres livres, Porta di Brandeburgo (Rizzoli, 1997) et

Il Piccolo Adolf non aveva le ciglia (Rizzoli, 1998), qui parlent, chacun

dans un registre différent, de Berlin et du nazisme. Les images remontent,

poussées par les mots, et avec elles remontent, comme des bulles d'air, les

visages, les cris, les odeurs, le bruit des bombes. "J'avais vécu l'histoire

sur ma peau d'enfant et j'avais essayé, longtemps, de l'occulter." Cette

fois, Helga Schneider étudie pour de bon les ouvrages d'histoire, les documents

d'archives. A presque 60 ans, elle déchiffre, une à une, les pages sombres du

nazisme. "C'était comme si j'allais à l'école, de nouveau", dit-elle.

Mais sa mère, évoquée en quelques lignes seulement, en page de garde, dans Il

Rogo di Berlino, reste un sujet tabou.

Il faudra l'opiniâtreté des journalistes de la RAI, qui persuadent Helga

Schneider de faire avec eux le deuxième voyage de Vienne, en 1998, pour qu'elle

saute le pas. Quelques mois après ce reportage à l'hospice, Helga Schneider

revient à Vienne. Sans caméra, mais avec sa cousine, la seule parente avec

laquelle elle s'entende. C'est cette rencontre, affreuse, poignante, que raconte

Laisse-moi partir, mère. Le livre devrait paraître l'an prochain en

Allemagne, mais aussi en Autriche, où l'ancienne Waffen-SS vit toujours. Elle ne

sait pas que sa fille a écrit ces livres. Le père non plus n'en saura rien, mort

en 1980. Helga Schneider, elle, rêve de Berlin. Elle n'ira plus jamais à Vienne.

"Les villes sont innocentes, j'ai mis ma vie à le comprendre",

sourit-elle. C'est avec sa cousine, qu'elle n'avait pas vue depuis les années

1940, qu'elle s'est remise à l'allemand, sa langue maternelle. Il lui manque du

vocabulaire et elle n'ose pas l'écrire encore : "C'est comme si un morceau de

mon corps était devenu insensible, comme si j'étais handicapée, ça me perturbe.

Mais je vais me rééduquer, ce n'est qu'une question de travail. J'ai très envie

de retourner à cette langue, elle me manque autant que Berlin." Helga

Schneider est sur la route. La sienne. Elle a fait, livre après livre, le gros

du chemin.

Catherine Simon

•

ARTICLE PARU DANS L'EDITION DU 16.03.02

DEIXE-ME IR, MÃE

Helga Schneider,

136 páginas

Berlendis e Vertecchia

Editores

Rua Moacyr Piza, 63

01421-030 - São Paulo - Brasil

Depois de 57 anos

de separação Helga Schneider prepara-se para rever sua mãe, uma senhora de 90

anos e de saúde debilitada. As duas são separadas desde o ano de 1941, quando

Helga e seu irmão Peter, ainda crianças, foram abandonados pela mãe que preferiu

seguir sua "missão" como guardiã nos campos de concentração e de extermínio do

3° Reich.

Lo sterminio dei tedeschi inutili

Paolo Marcesini

| |

La

forza della vita che dà forza al romanzo. Questo è il primo pensiero che viene

alla mente dopo aver letto Il piccolo Adolf non aveva le ciglia (in

uscita da Rizzoli), il primo romanzo firmato da Helga Schneider, la scrittrice

tedesca di origini polacca (da molti anni vive a Bologna) che con Il rogo di

Berlino, il suo esordio narrativo (venne scoperta da Roberto Calasso e il

libro, pubblicato da Adelphi, fu un autentico caso editoriale) ci aveva

raccontato la storia della sua infanzia trascorsa a Berlino negli anni bui

nazismo.

E’

la storia di una donna tedesca, Grete, che decide di ribellarsi al regime

nazista. Era bambina quando Hitler iniziava la sua ascesa al potere, era la

giovane moglie di un potente gerarca nazista quando il suo paese entrò nel

tunnel del terrore e della dittatura. Grete decide allora di lasciare il marito,

di lasciare il nazismo. Ma nel codice delle SS non è previsto che una moglie

lasci il marito, semmai viene tollerato il contrario. Allora viene rinchiusa in

un ospedale psichiatrico, resa innocua dagli psicofarmaci, e lì conosce la

violenza della repressione, vede con i suoi occhi migliaia di tedeschi

ammazzati, annientati. Malgrado tutto avrà la la forza (e la fortuna) di

reagire, di passare dalla parte delle vittime. Perderà un figlio, rischierà di

morire torturata dalla Gestapo, ma sopravviverà. La incontriamo quando, ormai

ottantenne sfoglia l’album delle fotografie, la testimonianza di un passato che

non può e non deve essere dimenticato. |

|

|

Anche Helga Schneider ha vissuto il Terzo Reich sulla sua pelle quando era

ancora una bambina. Sua madre la mise al mondo nel 1937, tre anni dopo sarebbe

arrivato suo fratello. Poi nel 1941 entrambi vennero abbandonati. "Mia madre era

nazista, una attivista iscritta al partito, una fanatica della prima ora. Era

una SS, aveva il compito di addestrare altre donne. Ha messo al mondo due figli

solo perché così voleva il Fuhrer, eravamo bracce ariane destinate al servizio

del partito. Mio padre combatteva al fronte, e anche lui venne abbandonato. Si

risposò con una ragazza molto più giovane che non riuscì mai a volerci bene.

Avevamo una matrigna, non avevamo mai avuto una madre. C’era la guerra, le

bombe, la fame".

Sua

madre, quella vera, l’avrebbe rivista solo trent’anni dopo, a Vienna. Mentre ci

racconta questo capitolo della sua vita non possiamo fare a meno di immaginarla,

mentre parte da Bologna, con il suo primo figlio tenuto stretto per mano: "Non

sapevo che fine avesse fatto quella donna, non sapevo più nulla di lei. Il

nostro incontro durò solo mezz’ora. Mi portò in una stanza dove conservava una

uniforme, la divisa nazista che indossava il giorno in cui venne arrestata ad

Auschwitz. La guardava con orgoglio. Prima di parlarle avevo trovato la forza di

rimuovere dalla memoria il ricordo dei primi anni della mia vita. Ascoltare di

nuovo quelle parole fu come prendere uno schiaffo in faccia".

Sua

madre era stata condannata per crimini minori dal tribunale di Norimberga. "Fece

solo sei anni di prigione, poi tradì i suoi compagni e venne rimessa in libertà.

Mi disse: il nazismo mi piaceva, con la morte di Hitler è finita anche la mia

vita. Non chiese nulla di me, della mia famiglia, dei miei figli. Scappai

via. Mentre scendevo le scale sentivo la sua voce: perché hai fatto quella

faccia, perché adesso te ne vai? Il treno che mi riportava a Bologna

sembrava non arrivare mai". Nel romanzo, anche il padre di Grete all’inizio

crede ciecamente nel nazismo e nelle parole di Hitler. Poi capisce il suo errore

e il dolore sarà immenso, come la tragedia che ogni giorno si consuma sotto i

suoi occhi.

Già,

Hitler, non si può fare a meno di parlare di lui. La scrittrice ricorda bene il

giorno in cui lo ha conosciuto, aveva sette anni. "Quando Berlino bruciava chi

poteva, mandava i suoi figli nel grande bunker dove Hitler viveva. Ci andai con

mio fratello e altri quindici bambini. Ci truccarono sotto una lampada al quarzo

perché Hitler non voleva che i figli della grande Germania fossero sporchi e

affamati. Poi arrivò, intorno aveva decine di guardie del corpo. Di fronte a me

avevo solo un uomo finito, un rudere. Trascinava un piede, un braccio era

rigido, le SS ci guardavano con il mitra spianato. L’atmosfera era lugubre, si

sentiva l’odore della morte. Mi diede la mano, la sua era umidiccia e

febbricitante, volevo liberarmi da quella stretta, ma non potevo. Mi guardò e

quei suoi occhi così magnetici e profondi non li ho più dimenticati. Dopo sei

mesi si sarebbe ucciso. Uscii da quella stanza e pensai: dov’è la libertà? dov’è

la giustizia?

Di sicuro non

abitava lì".

Anche la protagonista de "Il piccolo Adolf non aveva le ciglia" incontra Hitler,

ma il suo è un incontro piacevole, rilassato. E’ il 1925, gli anni della guerra

sono lontanti. Hitler è un leader di partito che incontra i suoi elettori nella

casa di campagna, la Haus Wachenfeld. Grete ci va con il padre, in mano tiene un

mazzo di fiori freschi. Lui in cambio le offre una fetta di focaccia al

formaggio e un bicchiere di limonata. E parla: "Se avesse potuto far capire al

popolo tedesco che l’immortalità cui aspirano le religioni era realizzabile

soltanto attraverso l’immortalità di una nazione si sarebbe già trovato a metà

di quell’opera che riteneva gli fosse stata assegnata dalla Provvidenza".

Nel

suo romanzo Helga Schneider racconta una tragedia rimasta sepolta nella memoria.

"In pochi ricordano che i nazisti inaugurarono i campi di concentramento

eliminando tutti quei tedeschi ritenuti inutili, i malati di mente, quelli

terminali, i mutilati, i diversi, i bambini handicappati, gli oppositori al

regime, la zavorra del paese insomma, i "pesi morti", gli inutili. Era un

programma di eutanasia collettivo. Le prime camere a gas vennero usate per loro.

Hitler disse che così andava fatto per il bene della nazione e i tedeschi lo

seguirono con entusiasmo. Era un incantatore di serpenti, gli uomini lo votavano

con convinzione, le donne, inspiegabilmente, impazzivano per lui. Facendo

appello alla teoria di Darwin sulla selezione naturale, teorizzò la selezione

artificiale. L’ultimo bambino down venne ucciso quando gli americani erano già

in Baviera ". Anche Grete, stordita dalle medicine, viene mandata dal marito in

una clinica per essere "rieducata" al suo ruolo di moglie. Ma dopo la clinica

arriva la camera a gas. Viene salvata da un bombardamento.

Un miracolo.

"Il

piccolo Adolf non aveva le ciglia" è un romanzo scritto con la pancia, una

storia raccontata con la forza di chi, storie così, ne ha viste tante. Non è la

"sua" storia, ci dice, ma la potrebbe essere stata. Lei che era una bambina

quando Berlino bruciava, ed era nuda, stracciata, chiusa in una cantina senza

acqua, senza cibo, senza nulla. "Ci salvammo per miracolo. Nella nostra cantina

arrivarono i russi e subito violentarono due ragazzine di quattordici e sedici

anni. Con mio fratello sentivamo le loro urla. Una di loro durante la notte

morì". Poi la guerra finì: "Mi sentivo rifiutata, da mia madre, dalla matrigna,

dal mio paese. Scappai, arrivai a Vienna con il sogno di scrivere e fare

l’attrice. Volevo una rivincita sulla mia vita. Intanto lavavo i bicchieri nelle

birrerie. Nel 1963, depressa, sola, decisi di fuggire per l’ennesima volta. Non

volevo più sentire parlare il tedesco, volevo altre facce, il sole. Arrivai in

Italia e qui la mia vita cambiò". La grande svolta arriva con un marito, portato

via troppo presto da una feroce malattia, quindi con la scrittura. "Sono una

testa dura che continua, dopo tanti anni, a ripetersi sempre la stessa domanda:

come è potuto accadere tutto questo?". Al posto della tradizionale dedica, la

Schneider ha pubblicato una frase tratta dal Times di Londra datato 24 luglio

1933: "Anche il peggior nemico di Hitler non può contestargli i privilegi, già

acquisiti, di una civiltà completamente rinnovata".

Non aiuta a

dare una risposta.

Leggi critiche di questo libro

qui

| |

|

The

Women's Review of Bookss |

|

|

|

SEPTEMBER 2004

The unmothering

Let Me Go by Helga Schneider. New York:

Walker & Company, 2004, 172 pp., $19.00 hardcover.

Reviewed

by Lisa London

A YOUNG

WIFE AND MOTHER OF TWO children becomes involved in local political activities.

She hires a babysitter so she can attend weekly organizing meetings. She gets

her mother-in-law to stay with the children so she can leave for one-, two-,

three-day trainings. She participates in local organizing drives and hands out

literature, and slowly her participation is recognized and rewarded--she moves

up in stature and rank. She assumes more duties and is invited to meetings with

higher level officials. But her mother-in-law complains of the time she spends

away from the children; her husband demands she stop her activities; and the

neighbors talk: "Why isn't she caring for the children? What kind of mother is

she?"

Twenty-one-year-old Traudi Schneider not only withstood this criticism from

family and friends, she seemed to invite it with her regular rejection of her

mothering duties. Finally, in an act of social rebellion, she left her husband

and children to enter fully a political life. To reject the role of mother and

move on, to "un-mother" oneself: Few women have the inner resources to carry out

such an act.

But Let

Me Go is not a story about an independent mother and her long-lost daughter.

It was 1941 when Traudi Schneider left her husband and two children. She did so

to become a proud member of the Nazi SS. In fact, Traudi Schneider was so

enthusiastic about her work that she was elected to guard the inmates at the

death camps: "Only the hardest, the thickest-skinned were destined for those.

That's why you were chosen for Birkenau, the most selective camp of all," she

was told. Traudi Schneider never recanted or apologized for her barbarous

participation in torture and murder. In fact, those continue to be the proudest

days of her life.

In Let

Me Go, Traudi's daughter Helga Schneider travels to the bedside of her now

90-year-old mother and transcribes in minute detail the conversation that

ensued. A document of the Shoah, the Holocaust, Let Me Go details

Traudi's experiences as a female guard. In her daughter's record of their

conversation, Traudi recalls numerous horrifying details about her desensitizing

training, witnessing torture, and enforcing camp rules: "'I had orders to treat

[the prisoners] with extreme harshness,' she crows, 'and I made them spit

blood.'" She goes on to describe the medical experiments carried out on Jewish

prisoners. Helga takes pain to fully document her mother's role in the camps,

which she presents without adornment or apology.

AND YET

FOR ALL OF ITS historical weight and importance, this is a deeply personal,

heartbreaking story. Although the mother who left and the daughter who was

abandoned are continually subsumed by the large, brutal reality at the heart of

the last century, their story is always there, pulsing just under the radar.

While an apparently straightforward statement like, "Yes, mother, I know, I've

read your file," refers to Helga Schneider researching historical documents on

Traudi Schneider's crimes against humanity, it also refers to a daughter

learning about acts of brutality committed by her mother. The two women share

the same blood, the same family history; despite what Helga might wish, she has

a connection to the woman who committed these acts. "What a sad couple we are,

mother, and what an absurd bond connects us," says Helga.

When Helga

meets her mother, she feels not anger but horror, not need but desperation, not

understanding but bewilderment. Her experience is not within the normal human

emotional range; she can't quite find language to describe it. Twice she has to

leave her mother's side because of panic attacks.

The

emotional layers are thick and complicated. When Helga first met her mother,

Traudi presented her with her SS uniform and wanted her to try it on. She tried

to give her daughter jewelry stolen from Jewish prisoners in the camps. When

Helga realizes that her mother is completely blind to her horror, she feels some

pity for her. But ultimately Helga is unable to reconcile her lifelong desire to

meet, understand, and connect with the woman who gave her life with her mother's

continued anti-Semitism and outright reverence for Hitler's doctrines.

As a

reader, I'm drawn to history books. But I'm one of those for whom history must

have a face. As a feminist, I seek out woman's voices, especially in those

places where I feel I've heard the men's chorus for far too long. Women's

experience of the Holocaust is one of those places where the historical and

literary records are still overwhelmingly male. For this reason, I was drawn to

this haunting and difficult book. What adult daughter doesn't struggle with the

emotional inheritance left to her by her mother? As a historian uncovering the

full weight and reality of the past, Helga Schneider excels. As a daughter

yearning to connect with her mother, she must, if she has a heart, necessarily

fail. Each time Helga uncovers one of Traudi's acts of brutality, she pulls

further away, as though, if she can collect enough evidence, she too will be

able to "un-mother" herself.

27-12-2003

Finally, Helga

Schneider's Let Me Go (Heinemann, March) is so bizarre that, if it were

written up as fiction, it would seem cheap and nasty. In 1941, four-year-old

Schneider was abandoned by her mother in favour of a career as an SS guard,

first at Ravensbruck and then at Auschwitz-Birkenau. In 1998 Schneider, now in

her 60s, is summoned to a nursing home in Vienna where her 90-year-old mother

lives with her gloating memories of the glory days of Hitler's final solution.

This is a powerful, painful book about moral responsibility and the

impossibility of understanding what makes some people, even those who share your

DNA, turn to evil.

Helga Schneider: My mother was a guard in a Nazi death camp

She had dreamt of

an emotional reunion. But when Helga Schneider traced the woman who left her as

a child, the awful truth was revealed. By Peter Popham

24 February 2004

Helga Schneider's mother walked out of her daughter's life at dusk on a chilly

autumn day in 1941. Helga was four; her baby brother, sleeping in his cot, was

19 months old. Nobody else was home. Traudi, Helga's mother, did not say where

she was going, or why, or for how long, or whether she was coming back. "My

mother shut the door behind her," Helga writes in her memoir Let Me Go, to be

published next month. "I wasn't to see her again for 30 years."

Helga Schneider's story is of a life of multiple abuses: by the selfish mother

who abandoned her young family with war raging; by the hostile stepmother who

took her place; and by the many dislocations that followed. But, as Let Me Go

relates, the wounds caused by her mother's departure were only the start. Thirty

years later she was to be devastated again when she discovered why her mother

had left.

Traudi had gone to join the Nazi SS. She underwent special training to qualify

as a concentration-camp guard. And when her training was complete she was

assigned to duty at Auschwitz-Birkenau, the most notorious of the Nazi death

camps, where, at the height of the operation to rid Europe of Jews, 12,000 men,

women and children were gassed to death every day.

After her mother's pitiless farewell - "So, auf Wiedersehen, meine Kleine," she

said as she walked out the door with her suitcase - Helga Schneider might well

have lived out her life without encountering her mother again. Her parents

divorced, her father re-married, the departed woman's name was never mentioned.

Helga, who fought her stepmother and ran away from home at 16, made a life of

her own, falling in love with an Italian boy she met on holiday, marrying him

and settling in Bologna.

Her mother could have been dead for all she knew or cared. But then Helga had a

child of her own, a son called Renzo. And recoiling from the chilliness of yet

another unfeeling mother-figure - this time her Italian mother-in-law, who

called her son "the little Austrian" - her thoughts turned reflexively to the

first woman in her life.

"When my son was two or three," she says in her small, bright, picture-crowded

flat in the middle of Bologna, "I started to think, 'You're a mother now, but

what's become of your mother?' So at a certain point the idea matured in me; now

I will look for my mother. Who knows - I might find a mother for myself, a

granny for my son, a new relationship.

"I wrote to my father to ask if he knew anything. He said no. I said, 'Where can

I find her?' He said, 'I don't know anything and I don't want to know anything.

It's better to forget all about her.'"

But Helga ignored his advice and, in 1971, she set off on the trail. "The only

thing I knew for sure was that my mother and father were born in Vienna," she

says. "So my reasoning was that if she came back after the war, she must have

gone back to her own city. I got a friend there to check the register of births,

marriages and deaths and the phone books for everybody with the name Schneider.

And I wrote to the five women who might have been my mother. And one of them

wrote back to say, 'It's me.' So I told my husband, 'I've found my mother. I'm

going to Vienna.' He couldn't come, so I said I'd go on my own. I took my son."

Helga knew nothing about the life of her vanished mother. Out of that nothing

she had fashioned a loving woman delighted to get her daughter back, and a

doting grandmother to her son. The disillusionment was swift. Traudi, a solidly

built, handsome blonde woman of about 60, showed no interest in Renzo. "She

didn't even look at my son. She gave him some biscuits and milk." And then - "on

some absurd pretext" - she took Helga into her bedroom. She went to the wardrobe

and took out a uniform.

"She said, 'I would very much like you to try it on.' I said, 'Why?' And,

because my father had never told me anything, I didn't understand. I even

thought that perhaps it was a costume for a play. She said, 'I'd like you to try

it on.' I said, 'Why?' She said, 'Because it's always been my dream to see you

wearing it.' I said, 'But why?' She said, 'Because I wore this uniform at

Birkenau.'

"After 30 years I had in front of me, not a mother, but a war criminal. And one

who was not penitent. One who still said it was right. I always recall a phrase

she used about the old days: in German, 'Es war so schön', it was so beautiful!

Nazism was so beautiful! She was always repeating this phrase... That was her

life, she was still in agreement with it. Still a Nazi. Still convinced that it

was a righteous cause."

Helga refused the uniform, refused also the handful of jewellery her mother

offered her, looted from victims of Auschwitz. When Helga realised what she had

been given, "I pulled my palms apart, and the jewels clattered to the floor."

Instead of a joyful reunion, the meeting with Traudi was a disastrous shock.

Within 40 minutes she was outside the flat, promising insincerely to return in

the afternoon. Instead, she boarded a train to Italy with Renzo and tried to

forget the nightmare.

"Something changed in my mind," she told me. "I realised I had never had a

mother. I had to come to terms with it. I had to tell myself, 'Enough, I can't

have a mother, I've never had a mother, I never will have a mother, enough...'

To protect your psyche you remove yourself. I didn't think about her any more."

Yet her mother was there all the time, a few hundred kilometres away over the

Alps. Another immensity of time rolled by. Helga, an aspiring writer since

childhood, continued to write books, which publishers continued to reject. Renzo

grew into a man, Helga lost her husband to cancer. And, one day in 1988, a pink

envelope bearing a Viennese postmark arrived in her letterbox.

"What on earth could be inside that disgusting pink envelope?" she writes in Let

Me Go. "I wasn't expecting any post from Vienna. I had left the city in 1963,

and I had lost contact with all my old friends."

The letter was from a woman who described herself as a "dear friend" of Helga's

mother, telling her that Traudi, who had become "a danger to herself and to

other people", had been put in a nursing home. "Your mother is approaching the

age of 90," the letter concluded, "and she could pass away from one day to the

next. Why not consider the possibility of meeting her one last time? After all,

she is still your mother."

Once again, Helga Schneider went over the Alps, alone this time and encumbered

with neither hopes nor illusions. She went reluctantly. "I didn't want to go,"

she says. "There didn't seem much sense in going to see one's mother for only

the second time in one's life. I knew practically nothing of her life, she knew

nothing of mine. But when somebody appeals to your conscience, saying, 'Look,

your mother is so old...' I thought to myself, one day someone will ring up and

say, 'Look, your mother is dead.' So I said, 'OK, I'll go.' I thought, let's

see, perhaps she has repented at last. Perhaps she's realised she got everything

wrong: the Nazi ideology, her fanaticism, the fact that she sacrificed

everything for that ideology."

In the home, daughter and mother - the mother terribly changed - confronted each

other again. Helga had gone there with her cousin Eva. "There, we're facing one

another," she writes. "She's old, thin - unbelievably fragile. She can't weigh

more than seven stone. A woman who, 27 years ago, was still a healthy, vigorous,

robust woman. I can't suppress a feeling of infinite pity.

"Finally, in the depths of those pupils, something awakens - an imperceptible

flicker, an uncertain flame... 'I'm your daughter.' 'No!' she says. 'My daughter

died long ago.'"

Her mother was in the final stages of senile decrepitude. But the blankness and

bewilderment sometimes lifted and she became lucid, especially when the

conversation turned to the days when she had been one of Hitler's elect and a

guard in the toughest camp in the Reich.

Traudi remembered the name Silberberg, a Jew who co-owned Eva's father's

factory. And, Helga writes, that memory led to another: Silberberg dropped

Traudi's name at Auschwitz "'in the mistaken belief that it might ensure more

considerate treatment for his daughter, it might even save her from the rat

poison!' And she cackles shrilly, winking at the bystanders."

The belief was mistaken, because it was not only her Nazi duty to suppress every

taint of humanity that arose in her; it was also her profound pleasure to do so.

The hardened corps of SS guards were the Nazi elite, and unflinching cruelty was

their badge of membership.

There was worse to come for Helga. Through the haze of senility, Traudi detected

that her daughter - like many people - had a guilty, furtive fascination with

all the vile things the Nazis did; and to keep her daughter before her eyes she

tossed off one appalling anecdote after another.

"'I had orders to treat [the prisoners] with extreme harshness,' she crows, 'and

I made them spit blood.'

'What? Did I support the Final Solution? Why do you think I was there? For a

holiday?'

'Not everyone died [in the gas chambers] at the same rate... Newborn babies took

only a few minutes; they pulled out some that were literally electric blue...'

'The fourth crematorium in Birkenau had no ovens... because it was never

finished. All it had was a big well filled with hot embers... The new commander

in Auschwitz found it terribly amusing. He used to line the prisoners up on the

edge of the well and then have them shot, to enjoy the scene as they fell

in...'"

Finally, Helga succeeded in tearing herself away, this time for ever. "I went

straight home to Bologna because I felt terrible," she tells me. "And I had a

panic crisis: waking up in the night, bathed in cold sweat, heart thumping, with

a terror of dying..."

Helga had never given up writing, but the medicine she was prescribed to

suppress the panic attacks killed off her ability to write. "I phoned my agent

and said, 'Look, I'm finished as a writer, I can't work any more.' And my agent

said, 'Why don't you try to write up this experience with your mother?'"

'Let Me Go: My mother and the SS' is published on 4 March (Heinemann, £9.99)

In Brief : Holocaust Memoirs

Sunday, May 30, 2004; Page BW11

Let Me Go,

by Helga Schneider, translated from the Italian by

Shaun Whiteside (Walker, $19), is a short reminiscence of a woman's

confrontation with her 87-year-old mother, who was once an enthusiastic SS guard

at two Nazi death camps. The book won't let you go until you've finished reading

the last page. Born in 1937, Schneider was abandoned by her mother four years

later. The mother may have run off with a lover, but this shadowy affair is

irrelevant. What is spotlit by this harrowing chronicle is her mother's hatred

of Jews. " 'I hated those cursed Jews. A horrible race, believe me. Pfui.' "

These feelings permitted -- and encouraged -- her to assist in diabolical

experiments on both men and women. This is the mother, now resident in an old

folks' home, telling Schneider about an incident involving two female prisoners

in one of the camps: "Two filthy Jewish scum . . . were taking revenge for

something or other, the whores. But of course they were found out, and they

ended up in front of a firing squad. Naked. But first they had to spend a

fortnight in the punishment block. They were in the dark with rats as big as

cats that practically ate them alive. When they got out they were mad with

terror and couldn't wait to get that bullet in the back of the neck.' "Schneider

concludes this passage: "She has been speaking through clenched teeth, with

hatred that still seethes inside her like incandescent lava." Whether the mother

has been psychotic all her life -- and there is plenty of evidence to support

this -- is not the chief concern of the author, who is caught between her

loathing for a woman she knows is evil and her instinctual urge to win her

mother's love.

The book opens in 1998, when Schneider and her mother met for

the first time in almost 30 years -- and for only the second time since the war.

The mother didn't recognize her own daughter. Did she have Alzheimer's, or was

she playing tricks? It's hard to say. Gradually, the old woman, in turn

spiteful, quixotic, tearful, angry, boastful (" 'I was in the Waffen-SS. I

couldn't permit myself the sentimentality of ordinary people' "), became more

articulate as her memory improved. She was crazy but she also capable of the

kind of cruelty few could dream up, let alone perform. How do you come to terms

with such a person?

Except for a handful of post-war German authors, we are

rarely given such a glimpse of life on the other side.

July 26 issue -

Let Me Go,

by Helga Schneider

Schneider's mother abandoned her at the age of 4 to become an

SS guard at Auschwitz. Ever since she learned that shocking truth as a grown

woman, Helga has wanted nothing to do with her. But in 1998 she hears her

mother's health is slipping and visits her in an old-age home in Vienna. Since

the ex-Nazi is totally unrepentant, it's an agonizing encounter. The author

can't bottle up her seething resentment, but she also can't help feeling flashes

of tenderness and pity.

—Andrew Nagorski

The New Zealand Herald

16.04.2004

Reviewed by MARGIE THOMSON

Helga Schneider:

Let Me Go: My Mother and the SS

It's reminiscent of Bernard Schlink's The Reader, but this

story is true, as I had to keep reminding myself. It's a memoir, or perhaps more

accurately, a report: of a 60-year-old daughter's final visit, in 1998, to her

90-year-old mother, who had been a member of the Waffen-SS, one of the fearsome

guards of Auschwitz-Birkenau. This is only the second time the daughter,

Schneider, has seen her mother since 1942 when she was 4, when the mother left

her and her baby brother. "Our mother had abandoned us to join the SS,"

Schneider writes.

As the narrative shifts back and forwards between the "now"

of the rest-home and the years of Hitler's Reich, this slim book reveals a

harrowing tale of destruction on both the small and large scales. At the core of

it all lie crucial, complex issues of moral responsibility. Schneider insists on

the guilt of this now-aged woman, proud and unrepentant to the last, still

dressing in the same colour as her guard's uniform, with a small hoard of stolen

Jewish jewellery in her bedroom, and revealing her crimes of hatred in the

camps.

The author also reveals a new category of war victim: the

children of the Reich unwillingly exposed to shame and horror, abandonment and

physical hardship. The monsters of the camps, we see, can only have been

monstrous parents, too.

Schneider's own emotional turmoil drags the narrative in

places yet, in the end, it's her thwarted hope for some sign of contrition, and

her irrational yet all-too-human longing to find maternal love that accentuates

the sordid inhumanity of both her mother and the regime.

St. Petersburg Times, Florida, USA

My mother, the monster

By ELLEN EMRY

HELTZEL

Published

September 13, 2004

"Let Me Go,"

by Helga Schneider, Walker, $19, 166 pages.

The trouble

with books about the Nazis is that most people think they are just about the

Nazis. The way history has left it, the Third Reich produced ideologues and

premeditated cruelty without peer; none of us could be so bigoted, so heartless,

so methodical in a madness that killed millions of innocents.

Let Me Go, a

memoir by the daughter of an SS guard at Auschwitz, forces us, at least to some

small degree, to reconsider this assumption. Short (166 pages) and piercing, the

book looks at a junior member of Hitler's regime a half-century after the fact.

It is the portrait of a despicable woman, but also a believable one. This is

because the author, Helga Schneider, cannot look at her mother as merely another

cog in the wheel of a murderous machine.

"She is my

mother; in spite of it all, she's my mother," Schneider writes. "Should I be

ashamed if, every now and again, instinct, my instinct as a daughter, gets the

better of morality, of history, of justice and humanity?"

As Schneider

tells it, she was barely of school age when her mother packed and left their

Berlin home, scolding the girl and her younger brother as if they had no right

to be dismayed over her departure. Because her father was at the war front,

Schneider ended up being raised by a stepmother who didn't like her. As an adult

she relocated to Italy, married and had a son.

When he was

small, she took him to see her mother once, in search of reunion and some sign

of grandmotherly impulse. But the visit was a disaster, and the two women broke

off contact.

Now it's

1998. The mother is 90 and in decline. Summoned for one last meeting at a Vienna

nursing home, Schneider shows up with flowers and a cousin who has been

recruited for moral support. It's hard to say what draws her, other than a need

to gauge her mother's sense of remorse.

As a guard,

the mother ushered inmates to their deaths and to medical experiments that

maimed or killed them. But her mother, it turns out, remains defiant, claiming

the "world didn't understand." Schneider uses flashbacks to capture her sense of

abandonment and her mother's obedience to the cause. But it's really this

latter-day confrontation that tells the story, revealing a mother who is mean,

manipulative and self-justifying, yet with a desire to be loved.

As their

visit progresses, the old woman strains for her daughter's attention,

negotiating her secrets for a new lipstick and the chance to be called mommy.

Mutti: It's a German word of love and connection that's completely absent from

Schneider's experience.

"She comes

over to me and asks in a hurt and doleful voice, "Am I not your mother?' And

with a certain mischief she starts pinching my cheek as though I were a little

girl. I nod mechanically, and she starts shrieking, "Then you have to call me

Mutti! Everyone else's children call their mothers Mutti . . .' "

With

exchanges such as this, Schneider exposes both the mother's cruelty and the

daughter's ambivalence. She marvels at her "irrational tenderness" toward

someone she would otherwise describe as a monster.

Schneider

tells her extraordinary story with honesty and self-awareness. Although

nonfiction, it brings to mind The Reader, Bernhard Schlink's bestselling novel.

As with that book, this one is about a woman who served the Nazi cause and went

to prison for doing so. In this case, however, there's clearly more culpability;

Schneider's mother was, indeed, a willing executioner. Let Me Go is the

daughter's attempt to come to terms with this legacy.

- Ellen Heltzel is co-author of the Book Babes column

which can be found at

http://www.poynter.org

Caffè Letterario

Helga Schneider

Lasciami andare, madre

"Sì, madre, lo so, l'ho letto nel tuo

dossier. Vi addestravano per sensibilizzarvi alle atrocità a cui avreste

assistito nei campi di sterminio: e a quelli venivano destinate solo le più

dure, le più coriacee.

Per questo tu fosti scelta per Birkenau, il campo più selettivo."

Un libro drammatico, in cui la tensione emotiva è

sempre altissima, in cui non succede nulla perché tutto, troppo, è già successo.

Protagonista è la memoria: quella di una figlia abbandonata da piccola da una

madre unicamente votata alla fede nazista. Ed è memoria di solitudine e di

mancanza d'amore, di fame e di paure e, più recente, è il ricordo di un altro,

unico incontro con quella madre praticamente sconosciuta, fiera del suo orrendo

passato, incapace di vedere il disgusto della figlia al prezioso dono di monili

d'oro sottratti agli ebrei e tenuti gelosamente nascosti in un cassetto. La

divisa da SS appesa nell'armadio, l'invito ad indossarla, quell'oro tenuto per

alcuni momenti in mano, prima di farlo cadere a terra inorridita, il dispetto

della madre alle sue reazioni: questo è quanto Helga ha sempre in mente di quel

lontano incontro avuto, già adulta, con la donna che aveva lasciato lei di

pochi anni e il fratellino minore, un lontano giorno del 1941, per andare a fare

la guardiana del campo di sterminio di Birkenau. Ripensa a tutto ciò

l'autrice, protagonista del libro, mentre si avvicina al pensionato in cui si

trova la madre, ormai vecchissima e non lontana dalla morte. Ha deciso, su

invito di un'amica, di andare a rivederla per un'ultima volta, ma questo

incontro la sgomenta, la fa stare male fisicamente, eppure sente che è giusto e

necessario che avvenga: deve sapere, deve capire se è o sarà mai in grado di

vincere l'ambivalente sentimento che prova per quella donna, bisogno e odio,

voglia di cancellarla e impossibilità a farlo.

Le ore che passa insieme a quella vecchia, fragile e aggressiva, falsa e

arrogante, in alcuni momenti umana e debole, spesso spietata e lontana, sono

piene di emozioni quasi insostenibili. Helga vuole sapere, vuole capire:

come può un essere umano abbandonare due figli piccoli per inseguire un sogno di

morte? come si può assistere agli orrori che si svolgono quotidianamente sotto i

propri occhi senza alcun turbamento? come è possibile vedere l'uccisione di

migliaia di persone, donne che stringono tra le braccia i figli neonati, vecchi

inermi, bambini di pochi anni, senza provare sentimenti di pietà? come può una

folle ideologia accecare a tal punto?

Vuole sapere da quella donna, sua madre, tutto ciò che ha visto, che ha vissuto,

che ha, o non ha, provato. Per raggiungere questo scopo la incalza con domande,

aggira le sue reticenze con l'inganno, insomma vuole capire, a tutti i costi,

se è in grado di tagliare definitivamente il legame con lei o se non riuscirà

mai a liberarsene del tutto.

Proprio in questa ambivalenza tra ragione e coscienza in lotta contro impulsi

profondi e primordiali, tra pietà che emerge davanti alla vecchiaia opposta

alla consapevolezza che, nell'apparente debolezza e nella nebbia degli anni

trascorsi, nulla è andato cancellato dell'antico male, sta la grandezza del

libro e la tragedia di una donna o forse di una nazione.

Questo è un libro della memoria, si diceva, e infatti è anche il ricordo dei

campi di concentramento e dei loro orrori, degli esperimenti su cavie umane, del

male fine a se stesso che là si praticava, visti attraverso lo sguardo

dell'aguzzino, a essere parte integrante di questo Lasciami andare, madre.

La Schneider, che ha rifiutato addirittura la sua lingua in un desiderio di

purificazione estremo, ci ha regalato un testo autobiografico drammatico, ma

anche un documento storico di fortissimo impatto.

Lasciami andare, madre di Helga Schneider

130 pag., Lit. 25.000 - Edizioni Adelphi (La collana dei casi)

ISBN 88-459-1593-X

Di

Grazia Casagrande