14-6-2002

THE NANNY

DIARIES

by

Emma McLaughlin and Nicola Kraus

| |

Star Tribune

Book review: The Nanny Diaries

Janet Maslin

Apr 24 2002 12:00AM

Sorry, Madam, but your

worst nightmare has arrived. It appears that the help has been taking notes,

and good ones. The help is very sharp-eyed indeed.

Apparently it has been noticed that you neither

cook nor eat, that you import toilet-bowl cleanser from Europe, that your

idea of a permissible outing for your 4-year-old son is a trip to the

trading floor of the New York Stock Exchange, and that you have been known

to sip Perrier while the little lad was desperately thirsty. How unspeakable

of your nanny to have noticed. |

|

|

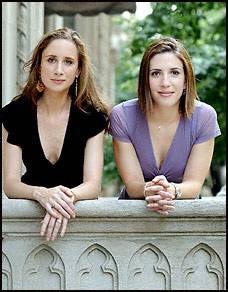

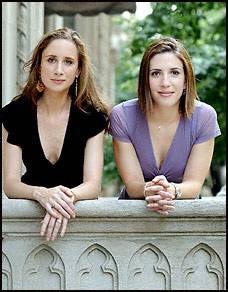

Emma McLaughlin and

Nicola Kraus, former nannies to the well-to-do in New York, have turned

their experiences into a best-selling book.

|

|

Then again, maybe she had the

right idea. Because the servant's-eye view is always satire-ready, and the

person in charge of child care has a splendid vantage point for skewering her

employers. Thus we have "The Nanny Diaries," a diabolically funny New York story

about a Park Avenue family and the college student who is hired to baby-sit. For

everyone in the household, not just the neglected son.

"The Nanny Diaries" is a

collaborative first novel by two recovering child-care workers who between them

claim to have worked for more than 30 New York families. However these two, Emma

McLaughlin and Nicola Kraus, were employed, they know their territory cold.

Their characters are the kinds

of women who instruct new employees: "Now the dry cleaner's number is on there

and the florist and the caterer." Yes, but how about a pediatrician? "Oh. I'll

get you that next week."

Their composite heroine, whose

actual name is supposed to be Nanny, is a vastly entertaining narrator and

impromptu social critic.

Given the author's

backgrounds,they could have written a nonfiction tell-all book, but the material

has been winningly transformed into fiction, thanks to an antagonist whom

readers will love to hate: Mrs. X, the quintessential spoiled, imperious,

spa-trotting matron.

What is she busy with all day,

"helping the mayor map out a new public transportation plan from a secret room

at Bendel's?" Whatever it is, it leaves only the most infrequent moments for

spending time with her son, and those moments are no fun for either of them. "Go

get into bed and I'll read you one verse from your Shakespeare reader," she

tells him, "and then it's lights out."

The son is named Grayer. And

after a rough get-acquainted period, he and Nanny bond out of self-defense.

They're in it together when Mrs. X insists that Grayer be kept wrinkle-free

before his portrait sitting, and when she makes him wear a Collegiate sweatshirt

before he has been accepted at that prestigious school. "It was a very

competitive year!" Mrs. X explains, upon learning that her 4-year-old hasn't

made the grade. "Grayer doesn't play the violin!"

Because the authors have made

fine sport out of shooting fish in a barrel, the X family also includes a gruff,

high-powered husband who supports the household in extravagant style but is

almost never around. Cheating on Mrs. X makes it hard for him to get to family

vacations to Aspen, Nantucket, Lyford Cay and other stops on their social

circuit and keeps him distracted even if he shows up.

Nanny, who is told that it's

quite unreasonable for her to want to attend her graduation from New York

University when the family needs her at its rented beach house, is witness to it

all.

Not surprisingly, "The Nanny

Diaries" fades slightly when the X's are out of sight, despite the boyfriend and

family matters that are meant to fill out Nanny's story. The heart of the matter

remains perfectly pitched social satire, from the children's birthday parties ("We

really had to put our heads together to top last year's overnight at Gracie

Mansion") to the kind of house where African, Venetian, Art Deco, Empire and

Winnie-the-Pooh styles heedlessly collide.

And in all the domiciles

described here -- places where it is deemed very important to have lavender

water in the steam iron -- the point is that nobody's really home. Nobody but

the servants and the children. This book is saved from self-righteousness not

only by the authors' cleverness but also by their compassion.

East Side Story

After 'The Nanny

Diaries,' The View From the Penthouse Is Greener Than Ever

By Alona Wartofsky

Special to The Washington Post

Monday, July 1, 2002; Page C01

NEW YORK

| |

Let's say, just for a moment,

that your bosses are heartless and nasty, and they underpay you. So you sit down

and write a book about them, and it becomes a huge bestseller. Sweet, sweet

revenge.

This is the enviable position

of Nicola Kraus and Emma McLaughlin, the former nannies who authored this year's

biggest literary sensation, "The Nanny Diaries." The book is a fictionalized

comic account of a nanny (named Nanny) who is employed by an affluent,

dysfunctional Park Avenue family. The Xes, as they are called in the book, may

be fabulously wealthy, but they are truly awful: Mrs. X, who keeps her lingerie

in labeled Ziploc bags, devotes her considerable free time to pampering herself

and exploiting her servants. Mr. X is a potbellied philanderer oblivious to any

concept of humanity. Their neglect of their small son is criminal.

|

|

|

Four months after its

publication, "The Nanny Diaries" is now in its 15th printing. There are 650,000

copies in print. It's been on the New York Times bestseller list for 15 weeks,

and foreign rights have been sold in 28 countries. Miramax bought the movie

rights for a reported half-million dollars, and Julia Roberts narrates the audio

version, which is also ringing up impressive sales. A second "Nanny" book is

already in the works.

Not bad for two first-time

authors, both 28, who say they wrote the book as a kind of personal experiment.

"We wrote it for ourselves, really," says McLaughlin. "We wrote it to share with

our parents and our close friends. And we wrote it to see if we could."

Kraus and McLaughlin met

several years ago while attending New York University. Once they discovered they

were both nannying on the Upper East Side, they became fast friends. "That

really cemented our friendship . . . trying to do the same juggling act of

balancing that kind of work with trying to complete our undergraduate studies,"

says Kraus. "We would point out to each other while we were in class that there

were so many nannies in the [literature] that we were studying, which was

interesting to us."

Several years after graduation

-- Kraus continued to nanny and tried to break into acting, while McLaughlin did

business consulting -- they started thinking about writing "a woman's story"

together. "We hit upon the idea of Nanny as a really good starting-off point,"

says Kraus. "It was such a profound experience for both of us -- the good and

the bad. It just felt like there was a lot of material there that needed to be

mined."

Because they've just finished a

photo shoot on a hot afternoon, Kraus and McLaughlin arrive for an interview at

the Upper East Side's Stanhope Hotel in heavy makeup that has succumbed to the

effects of sweat and gravity. They retreat to the bathroom to clean up, and when

they return, they are still wearing a lot of makeup and they are giggling.

McLaughlin is married. Kraus

has a cat. In conversation, they occasionally finish each other's sentences. Not

long ago, when the book tour brought them to an enormous suite in a Dallas

hotel, they were so overwhelmed by it all that they slept in the same bed,

talking and laughing into the night with the sheets pulled up to their chins.

They shop together, and they like to wear outfits that complement each other,

which may explain why both are wearing similar cleavage-baring frilly tops.

McLaughlin grew up in Upstate

New York, where her father taught college philosophy and her mother owned a

landscape design company. She tends to speak with a saccharine but firm,

no-nonsense tone that she may have picked up from some of her former employers.

The bubblier Kraus is a child

of the Upper East Side, where her parents own an art bookstore and she attended

private school. Neither Kraus nor McLaughlin says she was cared for by nannies,

though Kraus's family employed a housekeeper. "The landscape of Manhattan was

very different when I was a child," says Kraus. "The economy hadn't spiked to

the extent that it did when we were nannies."

The book devotes many pages to

mocking the materialism and pretensions of Manhattan's moneyed class, the sort

of people who dress their toddlers in $300 Bonpoint ensembles and buy toilet

cleanser imported from Europe. Nanny is instructed to prepare Coquilles St.

Jacques for the Xes' 4-year-old son, Grayer. The boy's permissible "nonstructured"

outings include visits to the French Culinary Institute and the New York Stock

Exchange trading floor.

Part of the considerable appeal

of "The Nanny Diaries" is this voyeuristic peek into the presumably magnificent

lives of the elite. "You're seeing a glamorous world in New York City, and

that's always had global appeal," says Miramax co-president of production Meryl

Poster, who is overseeing the film project. "This is like . . . a cousin of 'Sex

and the City.' "

But "The Nanny Diaries" may

have more in common with that old '80s nighttime soap opera, "Dynasty," in which

Joan Collins's wicked Alexis Carrington Colby would strive to ruin the lives of

everyone around her while nibbling on lobster and caviar. We love watching rich

people behave badly because they do everything in excess -- and because it

allows us to feel superior.

How ghastly are the Xes? They

are cruel to their son and their servants, but they are also vicious to each

other. As the marriage begins to disintegrate, Mrs. X retreats to a spa where

she refuses to take calls despite little Grayer's high fever and croup. When

Mrs. X is out of town, Mr. X's mistress moves into their apartment, where she

starts ordering the servants around.

As New York magazine critic

Daniel Mendelsohn has pointed out, "backstairs" literature -- the help's insider

account of how the well-off live -- "serves a crucial cultural purpose: not to

sell us on the haute life but, if anything, to reassure the middle classes that

the best possible thing is to be middle-class. Books like 'The Nanny Diaries'

allow us to . . . ogle the designer-decorated Christmas trees, the private

plane, the lazy days of cappuccinos and seaweed wraps, even as we sneer at the (cliched)

inability to have warm, loving family lives."

There are other explanations

for the book's runaway success, says Jennifer Weis, the St. Martin's Press

executive editor who paid a $25,000 advance for it after seeing a partial

manuscript. "It's a very talkable book," she says. "It touches on a lot of

issues that we are all thinking about and concerned about. It's a book that

people ask each other about, to reaffirm their own views about things."

A talkable book makes for

hype-building television appearances -- Kraus and McLaughlin have appeared on

"Today," "Entertainment Tonight," CNN and dozens of local channels around the

country -- which leads to more talk. "It struck a chord," says Miramax's Poster.

"People have a lot of issues about child care. But it's also juicy summer

reading. I think that it's mostly women who are reading the book, and I think

they're trying to guess. People always play games with comic books: Are they a

Betty or are they a Veronica? With this book, are they Mrs. X or are they more

like Nanny?"

Here in New York, "The Nanny

Diaries" spawned another guessing game, one that seeks an answer for the

tantalizing question: "Who is Mrs. X?" In March, the New York Times ran a story

that named one possibility as the model for the character: CBS correspondent

Lisa Birnbach, perhaps best known as the author of a different publishing

sensation, "The Official Preppy Handbook" (1980). Birnbach told the Times that

Kraus had worked for her as a babysitter.

Kraus and McLaughlin did not

approve of that story. "Unfact-checked. Unfounded," says Kraus.

"We have never in any venue

ever revealed names of people we worked for to anyone -- " says McLaughlin.

"Not to our agents, not to

anybody, ever -- " says Kraus.

"So that was the New York Times

sort of picking a fantasy and running with it," says McLaughlin.

Reached through her CBS office,

Birnbach declined to comment for this story, as did Alex Kuczynski, who wrote

the Times article.

Kuczynski's story also quoted

Robin Kellner, executive director of a Manhattan nanny agency, railing against

the book. Kellner said it was "unfortunate" that "someone has decided to imply

that their former job is a source of all this gossip, and exploit it and

capitalize on it."

McLaughlin shakes her head. "We

had no idea or intention while nannying that it would ever be something that we

would write about in any way," she says firmly. "I love nanny agencies and high

society co-opting the word 'exploitation.' "

Giatree Singh has worked as a

nanny for 17 years and 30 families, at least 20 of them on the Upper East Side.

" 'The Nanny Diaries' is factual," she says. "They're stating that it's fiction,

but it's factual. I myself have experienced a lot of those things that were

described in that book."

Singh, who is from Trinidad,

owns two copies of the book. She bought the first. The second was a gift from

one of her employers, a woman who inscribed the book: "To my dear friend and my

lifeline."

Seated on a bench in Central

Park's 96th Street Playground, Singh keeps one hand on an infant's stroller as

he sleeps through the afternoon heat. "I wish I had thought of it first. I

really regret not coming up with that idea," she says, and she's laughing. "I'm

going to put a copy of that book on my coffee table, right next to Nostradamus."

In recent months, McLaughlin

and Kraus -- who, between them, claim eight years' nannying experience -- have

often been asked whether an emigre from the Caribbean or Central America would

have written the same kind of nanny book. After all, Nanny is a college-educated

American citizen, with the option of retiring from nannying at any time. "A

woman from the Caribbean could absolutely have written this book," says

McLaughlin. "I mean, it's a novel.

"Do women from other countries

get terribly exploited in this job? Yes. . . . Are there terribly unfunny

stories out there? Yes. Terribly unfunny." She clasps her right hand at the base

of her neck. "This is an unregulated profession, completely unregulated. It

happens completely in the closet of our culture, and therefore, you name it,

we've seen it happen," she says.

Not long after "The Nanny

Diaries" was published, the Village Voice ran a story chronicling the struggle

of nannies -- many of them immigrants who are underpaid and otherwise abused by

their employers -- to unionize. "The Village Voice really set itself apart,"

says McLaughlin. "Really, it has been disappointing to be greeted for the most

part by a media . . . that was interested in running stories of he-said,

she-said, the mommy side of it, the nanny side of it. It was just so divisive."

At one point, Nanny bonds with

another full-time babysitter, a former engineer from El Salvador who is able

only once a year to see the sons she left behind. Finding a balance between

serious and comedic passages, say the authors, was part of the writing

challenge.

"I don't think either one of us

was really interested in writing a sad book or writing a funny book," says

McLaughlin. "We wanted to . . . write something that would take you in a lot of

different directions in a manageable way, that would really give you this full

experience."

This is why even though Mrs. X

may be one of the most hateful villainesses since Cruella de Vil, she is also

pitiable, which serves to complicate Nanny's feelings toward her. "That's out of

respect for nannies," McLaughlin explains. "The nannies that we knew and worked

alongside, no matter what country they were from, were incredibly, incredibly

compassionate -- not just about the children, compassionate about the women that

they worked for."

There's plenty not to like

about "The Nanny Diaries." The characters are cliched and the fun grinds to a

halt whenever the Xes are out of the picture. Nanny's family, parents and

grandparents are cloying, and her life away from the Xes is profoundly

uninteresting. And at times, it seems that Nanny is just as materialistic as her

employers, noting every designer in Mrs. X's wardrobe and rejoicing at the

castoff Prada shoes she gives her. The chapter titled "Holiday Cheer at $10 an

Hour" culminates with Nanny's shock and disappointment when she finds that all

the Xes have given her for Christmas is a pair of earmuffs.

Kraus, in fact, was the

ungrateful recipient of black rabbit earmuffs from Saks Fifth Avenue. "The issue

was not that they were earmuffs. It's, as we showed with Nanny in the book, it's

that she's at the bottom of the bonus totem pole," says Kraus.

"The majority of women who have

this job, with children of their own in outer boroughs that they don't see for

13 hours a day, or that they're sending their money to in other countries,

endure so much more disrespect and degradation than getting a pair of earmuffs,"

says McLaughlin.

Still, the earmuff fiasco, she

explains, seemed like a good way to show precisely where nannies are placed in

the servants' hierarchy. "The people who came to plump the pillows had gotten a

Gucci handbag and a fat check, and Nan had gotten nothing even close to that."

"You can have great shoes,

that's part of appreciating the aesthetics of life," says Kraus. "But that

doesn't mean that you have the right to stomp all over people."

March 10, 2002

'Who, Moi?' Mummies Ask on Park Ave.

By ALEX KUCZYNSKI

It is the question furtively whispered at cocktail parties, bandied about the

hallways of Manhattan's private schools and grumbled about behind bedroom doors

in Park Avenue prewar duplexes: Who is Mrs. X?

From the fictional point of view, Mrs. X is the piquant central character in

"The Nanny Diaries," a novel from St. Martin's Press that arrived in bookstores

about two weeks ago.

The authors, Emma McLaughlin and Nicola Kraus, worked as nannies in the

1990's for about 30 New York families, by their count. Drawing on their

experiences, they wrote a novel about the high-end misbehavior to which their

heroine, Nanny, is privy.

The characters are fictional, "the products of the authors' imagination,"

according to the disclaimer at the front of the book, so standard and ho-hum it

almost dares the reader to doubt it.

Just as Lexington Avenue must rumble periodically with the subterranean roar

of the IRT, the limestone and brick canyons of Park Avenue must also tremble

with the gossipy roar of a who's who parlor game. Guessing games have

entertained seasons past. Who was the real-life person who inspired the mistress

in "The Bonfire of the Vanities?" What about Mr. Big in "Sex and the City?" And

which society wife was a Madame Claude girl?

"The Nanny Diaries" looks like this year's Manhattan succès de scandale,

already earning the authors a Miramax movie deal, acclaim from some quarters as

Chekhovian social narrators and denunciation from the yummy-mummy set as pure

opportunists.

The book portrays the self-absorbed Mrs. X as a stay- at-home Park Avenue

mother, who does not seem to do much of anything except her nails. She stores

her lingerie in labeled Ziploc bags. Obsessed with her Prada shoes and

coordinated Lilly Pulitzer outfits, she cares solely about status and

appearance. In one scene, she asks Nanny, the novel's narrator, to make sure

that her toddler son, Grayer, is suited up in a Collegiate School sweatshirt for

a picture to send to friends, even though he has not yet been admitted to that

bastion of private education.

Not fair! say the real-life mothers of this world. Helen Schifter, a resident

of Park Avenue and the mother of a 7-year-old daughter, said in her circle it

has been suggested that the authors were inflicting vicious untruths upon

innocent employers.

"People I know feel it is very biased and mercenary," said Ms. Schifter, who

has not met the authors. "I think these two were very calculated and said,

`Let's make some money, we'll be the Candace Bushnells of the nanny world.' "

Like Ms. Bushnell, who turned her observations of New York social and sexual

habits into "Sex and the City," Ms. McLaughlin and Ms. Kraus observed the

private lives of New Yorkers and told the hired help's side of the story.

Ms. Schifter said she had read only passages from the book, but the tone

struck her as patronizing. Most of her friends, she said, were simply boycotting

it. But she conceded that there are parents who are not kind to their nannies.

"I will admit there are a few bad apples out there," she said.

Ms. Kraus found inspiration for fictional bad apples at 1000 Park Avenue, the

building where she lived with her parents, who run an art bookstore on the Upper

East Side, while she was working as a nanny. A Miramax executive who spoke on

the condition of anonymity said that one of the models for Mrs. X was Lisa

Birnbach, a CBS correspondent who does on-the-air stories about child care on

"The Early Show" and who used to live at 1000 Park Avenue.

Ms. Birnbach, reached at her CBS office, confirmed that Ms. Kraus had worked

for her and at least one other tenant of the building as a baby sitter.

"I considered her more of a play date for my child," Ms. Birnbach said. She

would not comment further.

There is little similarity between Mrs. X and Ms. Birnbach. The real- life

1000 Park Avenue is at 84th Street. The building in the book, the fictional 721

Park, would be at 71st Street. Ms. Birnbach has a career. Mrs. X does not. Mrs.

X's husband is a banker. Ms. Birnbach's husband, Steven Haft, is a producer. And

those who know Ms. Birnbach, the principal author of "The Official Preppy

Handbook," published in 1980, attest to her polite manner, solid reputation as a

reporter and general regard for others.

But there are similarities. Ms. Birnbach has dark hair. So does Mrs. X. Mrs.

X is an acquaintance of a famous shoe designer and his wife, who comes from a

political dynasty. Ms. Birnbach is an acquaintance of the shoe designer Kenneth

Cole and Maria Cuomo Cole, the daughter of the former Governor and sister of

Andrew M. Cuomo. And Mrs. X, the narrator complains, thinks of Nanny only as a

play date for her child.

Another woman who was named as a possible model for Mrs. X, one who still

lives at 1000 Park Avenue, did not return phone calls for comment.

Last week, Ms. Kraus said she did not think it inappropriate to use former

neighbors as fodder, nor did her parents, who still live at 1000 Park. "They are

very proud of me," she said. She added that she had never mentioned Ms.

Birnbach's name to anyone at Miramax.

Ms. McLaughlin, her co-author, said, "It is drawn from our experience but is

a work of imagination."

For all the hand-wringing and who- moi? righteousness, there are plenty of

mothers who are snickering. Ileene Smith, a senior editor at Scribner and a 1000

Park resident, said that the novel offered some keen insights into the mind of a

certain kind of cosseted Park Avenue mother.

"Chekhov must have been thinking about Park Avenue when he said every family

has a secret," she said.

Heidi Selig, an Upper East Side mother whose friends are reading the book,

said "The Nanny Diaries" is nasty, sure, but if you can't épater the

bourgeoisie, whom can you épater?

"Why isn't it permissible to poke fun at these women?" she said. "Lighten

up."

At a book-signing last Thursday night, about 100 people crowded sweatily into

the Lenox Hill Bookstore to eat tiny sandwiches of salmon and cream cheese,

drink white wine and listen to Ms. McLaughlin and Ms. Kraus talk about their

nannying experiences.

"The tenor of the novel is in no way an exaggeration," Ms. Kraus pronounced.

"Wow!" said Elizabeth Kingdale, a nanny from England who has worked in

California, Ohio and New York. She added that she was curious whether New York

mothers were as awful as the book made them out to be. "I guess it depends on

the family. I've been lucky."

The novel has had an immediate effect at some nanny agencies. Robin Kellner,

the executive director of the Robin Kellner Agency in Manhattan, which provides

live-in household help like nannies and nurses, said that the novel is unfair

and has prompted calls from families.

"I can't believe any mother would think this was acceptable social

commentary," she said. For families with help, she said, issues of trust,

privacy and security are central.

"I think it is unfortunate," she added, "that someone has decided to imply

that their former job is a source of all this gossip, and exploit it and

capitalize on it."

Ms. Kellner said families who have heard about the book have asked her if

they can trust the help they hire not to write or talk about their personal

lives.

Clifford Greenhouse, the director of the Pavillion Agency and the Nanny

Authority, both in New York, said all of his nannies sign a confidentiality

agreement as a condition of being placed by his agencies.

At 1000 Park, a resident who did not want to be identified said that the

building ought to institute rules against somebody's fictionalizing the lives of

other tenants. "Last week, the board sent out a memo about the weight limit of

your dog," he said. "And now we learn that one of our residents was a snitch. I

think that's a more important issue."

Alexandra von Furstenberg, an Upper East Side mother, said that she protects

her family by asking prospective nannies to sign a confidentiality agreement.

Her nanny, she said, is fascinated by "The Nanny Diaries."

"She said the two nannies are going to be at Barnes & Noble, and she asked me

if she could go," Ms. von Furstenberg said. "Of course I said yes. It's not like

she's going to side with them. She just thinks it's funny."

Ms. von Furstenberg paused.

"And I guess you can chuckle about it. If it's not you."

| |

Nanny Cam

Park Avenue

mommies like to keep an eye on their children's keepers. But a new novel

shows that the nannies are just as likely to be the ones taking notes.

From the

March 4, 2002

issue of New York Magazine

BY DANIEL MENDELSOHN

The

Nanny Diaries, Emma McLaughlin and Nicola Kraus's gimlet-eyed novel of

dysfunction in the 10028 Zip Code, begins with what you fervently hope is a

big fat lie: a "Note to Readers" insisting that while the authors worked as

nannies for a total of more than 30 New York City families, the "characters

are the product of the authors' imagination." Damn. The whole point of

reading a book like this is to get the dirt on real people -- in this case,

the kind of really rich people who make you glad you don't have a billion in

the bank; and I, for one, would be inconsolable to find that the

crack-addicted ex-beauty queen who has frosting fights with her 4-year-old

in a vast East Sixties townhouse, or the Park Avenue fortysomething who

alphabetizes her panties by designer, turned out to be products of anyone's

imagination. |

|

Nicola

Kraus, left, and Emma McLaughlin parlayed eight years of nannyhood into a

novel |

Anyway, could anyone really

dream this stuff up? I don't mean the plot: This one -- about a nice

middle-class girl who goes to work for a seriously rich, seriously wretched

family from whom she takes a lot of abuse until a liberating showdown -- has

worked like a charm in everything from Jane Eyre to The Sound of Music.

Here, our heroine (inevitably named Nanny) is an NYU child-psych major who takes

what she thinks is a part-time job looking after 4-year-old Grayer X (yes,

that's the surname) of 721 Park Avenue, only to find herself reduced to serfdom

by her trophy-wife employer, who's too busy with pedicures and "committee work"

to make contact with her own child. Or, for that matter, with anyone else: She

communicates with Nanny by means of exquisitely calligraphed -- and exquisitely

passive aggressive -- notes. ("I was wondering if you could throw something

together for Grayer's dinner, since I won't be home till eight. He loves

Coquilles St. Jacques . . . ")

But Nanny's story isn't the

point here. Yes, there's the escalating conflict with Mrs. X, and yes, there's

an ongoing flirtation with a nice boy in the Xes' building, and Nanny's lurching

progress toward graduation, to give the novel forward momentum. (That there's

momentum at all is a nice bonus: There is more writerly flair here than either

the double authorship or the predictable set-up would lead you to expect.)

But the wicked fascination of

this novel lies in all the wacky tidbits about life in the social stratosphere

-- people for whom a summer in Nantucket rather than the Hamptons is a bold step

in the direction of "diversity." The "impromptu" barbecues featuring watermelons

sculpted into busts of former presidents; the highly paid "problem consultants"

whom attenuated matrons must hire in order to fire their underpaid help; the

Park Avenue ladies who buy studios in the same buildings as their fifteen-room

duplexes so they can have "someplace for a little private time" away from little

Darwin or Iolanthe -- this kind of folly is irresistible to read about.

It's worth wondering why. If

"backstairs" literature -- the butler's or cook's or governess's

eyes-to-the-keyhole account of how their rich or famous employers live -- has

always been popular, it's because it serves a crucial cultural purpose: not to

sell us on the haute life but, if anything, to reassure the middle classes that

the best possible thing is to be middle-class. Forget about "Let them eat cake":

Books like The Nanny Diaries allow us to eat our cake and have it, too --

to ogle the designer-decorated Christmas trees, the private planes, the lazy

days of cappuccinos and seaweed wraps, even as we sneer at the (clichéd)

inability to have warm, loving family lives. Mrs. X may have a dressing room the

size of your apartment, but philandering Papa X rarely makes it home from the

office. Both parents make Medea look like Mary Poppins: The attention-starved

Grayer pathetically carries around his dad's tattered business card like a

totem.

I couldn't help thinking that

Grayer's been neglected by his creators too. It's strange, given the amount of

time the authors have spent around kids, that they haven't managed to conjure a

memorable child character. This boy is sort of generically endearing -- he cries

and snuggles and sleeps on cue -- but although you're constantly told that

Nanny's love for the boy is what keeps her from quitting, you never really feel

it. Of course, children aren't really the point here. They are, if anything,

just as much an "accessory" to the authors as they are to the emotionally frozen

parents, whose overdecorated, undernourished lives are the real object of a

satire whose barbs are sharp but don't go all that deep. "I'm distracted from my

thoughts of the Xes by the trappings of the Xes," Nanny hopelessly realizes in

the final pages of this very funny book. So, it would seem, are the authors; so

-- deliciously -- are you.

The Nanny Diaries

By Emma McLaughlin and Nicola Kraus.

St. Martin's Press; 320 pages; $24.95.

This

life: A spoonful of sugar ...

As a

new book lifts the lid on the New York nanny scene, James Langton speaks to a

real-life Mary Poppins

WHILE

Manhattan's mothers-who-lunch spend their days with low-fat lattes and spinning

classes, somebody else is looking after the children.

That

somebody is the nanny. She dresses and feeds them. She folds clothes, finds

teddy and cleans. The only difference between the nanny and a real mother is she

doesn't share a bed with a $750,000-a-year banker.

But

nannies are taking revenge. Published last week, The Nanny Diaries may claim to

be 'fiction' but don't believe it. Nicola Kraus and Emma McLaughlin have written

what has been described as an 'acidly funny' novel based on eight years caring

for the offspring of wealthy families. The book was recently bought by Miramax

films for £300,000 and threatens to do for childcare what Bridget Jones did for

big knickers.

The

Diaries charts the bizarre relationship between Nan and her mega-rich employers,

Mr and Mrs X. Hired as part-time help, Nan quickly finds her own life as a

college student comes very much second to the demands of Mrs X, who is too busy

to shop for goodies for party gift bags and certainly too busy to accompany her

four year old to his playtime appointments. As the family's dramas mount,

divorce looms. While Mrs X copes with the crises by shopping, it's Nan who

realises she's the only one concerned for the child.

Manhattan isn't short of nannies -- but listen to the accents on the swings at

Central Park playground and you'll soon realise it's the daughters of Albion

(and a fair few from Erin) who are the real surrogate mothers of New York.

'They

called me the Mary Poppins of the Upper East Side,' says Laura, a 32-year-old

nanny from Lancashire who has 15 years' of stories. With several piercings and a

tattoo, she doesn't look much like Poppins, and sounds more Julie Walters than

Julie Andrews, but to the mothers of Park Avenue she could have dropped from the

skies with an umbrella and a spoonful of sugar.

She

arrived in New York aged 17 and was placed with a family by an agency. She

lasted three months. 'It was horrific. They expected me to clean a five-storey

brownstone and look after a three year old. They had no regard for me, even

though I was looking after their child.'

She

found ice cream was considered a nutritious breakfast for an infant and the two

hours between coming back from the shops and dinner was enough for parental

bonding. 'They don't know what love is. They only know what can be bought.'

She

soon found her true worth. A good nanny can earn $1000 a week in Manhattan, with

private health care. Then there's the Christmas bonus. 'I know of one girl who

got $10,000,' she says.

It's

hard-earned, though. Fathers are barely seen after a day grappling with the

financial markets. And while wives may pause from the social whirl to give

birth, it's only for a moment -- Laura was looking after a baby at three days

old. 'And the mother had a wet nurse so she didn't have to get up at night. She

said her first word to me. It was 'Momma'.'

There

are possibly thousands of British nannies in New York, very few with the proper

papers. They do it for a fistful of dollars and the chance to live in the most

exciting city in the world.

Laura

took a job in a shop after her last post as she was becoming too attached to the

child in her care. Now she's thinking about starting a family of her own. But

she says: 'If I do have a baby, it's not going to have a nanny.'

Mummy can't buy you love

In the past nanny might

have known best, but now mummy doesn't know at all and couldn't care less

Shane

Watson

Friday March 1, 2002

The Guardian

The list of things we would rather not talk about is a

fair indicator of the state of the nation's psyche, especially since ours will

differ so dramatically from that of, say, the Americans. Take up-the-bum sex:

you can see it on the telly most nights of the week, but try canvassing opinion

on the subject (after the film of Bridget Jones's Diary was the obvious

opportunity ) and you quickly realise that it is not the taboo-free topic that

the makers of Club Reps would have us believe.

Money spent on clothes is

another good one: show me the woman who doesn't, when asked where she got her

designer coat, start bleating about how she found it in the bargain bucket, and

I'll show you someone who doesn't own a red passport. And then there's the whole

bizarre cover-up regarding the contract between the affluent middle classes and

their childcarers - the relationship that dare not speak its name. We like to

call them nannies, but they would more accurately be described as the People

Without Whom These Families Would Disintegrate.

Nannies now differ from those

of previous generations in one significant detail: they are running the show

single-handed. This is something we've all known for some time (there's a tenner

for anyone who has ever spotted a mother-and-child combo on the streets of

Chelsea, as opposed to children plus wan-looking antipodean) but, none the less,

the rule is to act like they're just helping out a bit (and don't they cost a

fortune? I mean it's not brain surgery).

At least in New York all such

pretence has been shelved with the publication this week of The Nanny Diaries, a

novel based on the co-authors' experiences of looking after the offspring of

wealthy Upper East Side families. Yes, you've guessed who's going to the

toddler's play appointments and who's putting in an hour's bonding time between

shopping and going out to dinner. Miramax has bought the film rights and we can

look forward to watching the selfish parenting habits of Manhattanites on the

big screen soon. As to whether it will bring us any closer to acknowledging that

the same teenage aliens are running the homes and raising the children of most

high-income couples in Britain, who knows?

No one's suggesting that paying

for childminding so that women can work isn't the best idea since the pill, but

this new relationship goes way beyond that. This is keeping your children at

livery, occasionally giving them a turn around the paddock so the guests can

admire their glossy coats and perfect schooling. What has changed is the

overwhelming desire of the well off to control their lives right down to the

last button. They want children; they've just got a lot of demands on their

time, so they prefer to focus on that particular project in those moments when

they would have been mountain-biking or listening to classical music.

Loss of control is a big fear

for the modern parent (see the success of the maternity nurse Gina Ford's baby

book, which advocates a rigorous routine) along with the fears of looking

foolish, being less interesting, being too tired and (for the women) descending

into first-wife material. Similarly, there are plenty of well-off mothers who

are not only too posh to push but far too pushy to hang around watching junior

finger-paint.

In the past, nanny might have

known best, but now mummy doesn't know at all and couldn't care less - she has

far more important things to do than potty training. So nanny is the only one

who can cope with three children, the dog and the shopping, the only one who

doesn't mind sitting through Jack and the Beanstalk, again. And if nanny leaves

and there's a week's gap before the arrival of her replacement, you would think

that Mrs Holland Park had been dropped in the jungle with a wet box of matches

(she pays "through the nose" for an emergency stopgap, which is, per day, what

her yoga teacher costs per hour).

Not everyone with the money to

pay for full-time childcare is as child-friendly as Herod. It's just that the

well off are in the habit of getting things done their way and "mother" does not

register on their statusometer, unless it's as a bonus interest, as in "I run a

boutique and I'm a mother." Lest we should tut-tut too much, can you honestly

say that you rate a 19-year-old Aussie who takes 24-hour responsibility for

someone else's baby higher than a shop owner who gets her picture in the paper?

Well that's what Mrs Holland Park thinks, too.

Week of March 13 - 19, 2002

Women Raise the City

by

Chisun Lee

The

Help Set Out to Help Themselves

Domestic Disturbance

They

picketed a midtown bank and an East Side embassy where their bosses worked,

demanding unpaid wages through bullhorns. They brandished signs on a

West

Village sidewalk

and before a picket fence in

Queens, denouncing families for abusing and shafting

their household workers. They organized in playgrounds, talked reform over

dinners they cooked each other, and together mapped a road to a more dignified

life.

But they were

supposed to stay home.

They were

supposed to be too tired from working 50, 60, or 80 hours a week. Too

discouraged by earnings of a few hundred dollars a week or sometimes a month.

Too frightened, because many of them are not supposed to be in this country, and

none can afford to lose a job. The Nanny Diaries, a comic new novel by

two NYU graduates who once worked on

Park Avenue,

has caused a sensation with its titillating trade secrets, but these ordinary

workers are still struggling to expose the grimmer truths.

Indeed, a package

of measures set to be introduced in the City Council this month is proof of a

growing labor movement among New York's nannies and housekeepers. Too dispersed

for a traditional union, these women have typically fended for themselves in the

insulated, highly personal setting of private homes. The proposals, however,

mark a peak in momentum that has been building for years, as the workers, who

call themselves Domestic Workers United, have gained supporters and lobbied

legislators. It will be the first time in history that the city acknowledges the

special burdens of domestic workers and considers reforms to relieve them.

"This is a

community whose rights, I feel very strongly, are not being protected," says

Gale Brewer, the

Upper West Side

councilmember who has taken the lead in pushing proposals for a local law and a

resolution, which requires a vote but lacks legal power. The community she

speaks of could number in the tens or hundreds of thousands. Absent an official

tally, industry observers look at estimates of

Caribbean,

Asian, Latino, and Eastern European immigrants, who make up the vast majority of

workers, and numbers of potential employers.

The proposed law

applies to placement agencies, which are estimated to transact about 50 percent

of the city's domestic work for a commission of 10 to 15 percent of a worker's

annual salary paid by those hiring. According to a recent draft, it seeks to

establish a "code of conduct" reflecting basic labor rights such as a minimum

wage, overtime, and Social Security payment—an indication of the profession's

arrested state. Agency heads who failed to obtain employers' signatures

acknowledging the code would face license suspension or revocation, a fine, or

imprisonment up to one year.

Enforceable

through the Department of Consumer Affairs, the law would "impose an official

standard on agencies to impose standards on employers," says Brewer's chief of

staff, Brian Kavanagh. "This gets rid of the ignorance defense" both plead,

sometimes sincerely, when accused of flouting labor laws, he says. Agencies are

not legally required to monitor how workers fare after placement, nor is there a

mandatory grievance process. The head of one reputable

Manhattan agency says a "very good rapport" with

workers is her process.

The accompanying

resolution would express a more radical vision of rights for all domestics,

whether employed through agencies or on their own. A draft refers to "the rights

of all workers to regularize their immigration status, [and] to organize." It

calls for reforms to federal and state labor laws that currently exclude

household workers and advances a set of "standard guidelines, "not only for

wages and hours but also for benefits like vacation and sick days.

"If you've got

councilmembers across the city agreeing that this is the standard, that should

help to bring this issue to the attention of state and federal legislators, and

. . . provide the basis to bring other people into the movement," says Kavanagh.

Mistreated domestics, he says, could consider their local legislator to be an

official advocate where none had existed before.

The actual

penalties involved are fairly mild, leading council proponents to hope for a

smooth passage. The measures would require little or no additional funding and

demand no more than employment norms widely accepted in other industries. But

the desired effect, say supporters, is no less than a sea change in the public's

understanding of domestic workers' rights.

These

workers include housekeepers, cooks, nannies, and the many who serve in between,

yet the fair-pay question often raises the issue of child care affordability.

Certainly the pending proposals will not resolve those daunting economics. The

minimum legal cost of employing a household worker in New York City for 50 hours

a week is about $14,000 a year plus taxes. Day care, while more affordable, is

scarce and lacks the convenience of in-home care.

Many employers

strive to pay more than the minimum, recognizing the near impossibility of

surviving on such a sum. Jill and Bob Strickman-Ripps, who live and work out of

two loft apartments in Tribeca, can do so more generously than others. She owns

a casting company; he is a commercial photographer. They hired Eunice Easly at

$350 a week in 1997, steadily raised her to $540—about $28,000 annually—and plan

an increase for the additional care of their newborn son. The parents "are very

fair," says Easly. They provide her with health insurance and paid her through

the six weeks she needed to recover from a recent operation. "How else was she

going to pay her rent?" says Jill Strickman-Ripps. "What's most important to us

is that the person who cares for our children feel good about us."

Yet in Eddie and

Randi Rosenstein's case, good intentions only stretch so far. With two young

children, they had to move from

Brooklyn's

fashionable Boerum Hill to a first-floor rental in Ditmas Park. He is an

independent filmmaker, she a pediatric physical therapist. Their income

precluded even the cost of a nanny agency.

Through word of

mouth, they hired a

Caribbean woman who, Eddie Rosenstein says, "had this

huge fear that we were these wealthy employers who were taking advantage of

her." The nanny declined to be interviewed. Rosenstein gives an estimate of her

salary, over $20,000 a year plus taxes. "This is all we can afford, period," he

says. Their child care expense, including part-time day care for their older

son, "is awesome," he says. "It's more than we used to make collectively."

However, says Rosenstein, who is filming a documentary about low-wage workers,

"As much as we're doing for her, I can imagine how hard it is to get by on what

we're able to give her." He says the parents who pay less and expect more breed

resentment that projects onto concerned employers like him.

Carolyn H. de

Leon, an organizer who started her 10-year nannying career at $2 an hour, says

she can sympathize with parents' financial crunch. "Many of us have children,

too. We have even fewer options for child care." Yet in the families they work

for, she says, "there is saving going on for college tuitions, for summer trips.

Many of us cannot save one penny, even working all the time." She commends the

parents who pay a living wage, but says, "we can't just count on getting good

employers, because there are plenty of bad and ignorant ones."

Indeed, the

proposed council measures challenge some long-standing industry conditions—low

wages and long hours, worker isolation, and lack of official concern—that keep

employers in control. Despite fair and generous agreements, these circumstances

nevertheless allow for thousands of working women to be overworked, underpaid,

and sometimes abused. There is a moral imperative that, reformers hope, will

deflate any opposition.

In fact, moral

authority was all that a half-dozen members of Domestic Workers United brought

to their first meeting with Brewer, on February 12. They could deliver few votes

or donors. Most had never met an elected official.

Nahar Alam, an

activist with six years in domestic work, gestures toward a friend seated next

to her. She explains on behalf of the Bengali speaker, "She lost one job because

she was sick. She was sick because she was working 18 hours per day. [Employers]

are taking so much advantage. They hire, they fire. You cannot do anything. We

get two, three dollars an hour. Immigrants in particular. Even if you have a

green card, it doesn't matter."

Jacqueline

Maxwell, an African American, adds that she has had similar problems. Moreover,

paid vacations, sick leave, and health care are rare. Says Faye Roberts, who

raised three daughters while working here, pregnancy or missing work to attend

to one's own children can warrant a dismissal.

Verbal and

physical abuse are more common than workers like to admit, say the women, and

job security is a joke. Plenty earn less than the legal minimum, especially

considering uncompensated overtime. And because no one is telling the employers

to stop, the abuses go on.

The heartfelt

pile-on gets to Brewer fairly quick. "You need backup," she says. "We will

definitely move on this."

The women have

won over a growing list of councilmembers, including Christine Quinn, John Liu,

and Charles Barron, simply by recounting their own experiences. Bill Perkins,

the council's deputy majority leader, says, "I'm on board by legacy." His

grandmother, an African American, was a household worker.

"These people

have historically been exploited, treated like peons," he says. Set to introduce

his own bill proposing a living wage for certain service workers, he says of the

pending domestic work package, "It helps to define us as an institution in a

progressive way, in a way that's responsive not just to landlords or business

interests or wealth, but also to those who are exploited, and whose exploitation

is silent."

The officials did

not even meet Estella Ngambi, who left her young son in Zambia and came to New

York to support him. She keeps house for a tennis instructor for $350 a month,

an amount she says she hasn't seen since December. She says she sleeps in his

kitchen on a blanket, instead of on an air mattress reserved for guests. She has

no friends to take her in, and no funds with which to escape.

Worse cases have

appeared in recent years under headlines screaming "Modern-Day Slavery" and

"Beatings and Isolation." Many of these involved third-world migrants brought

into the U.S. on special visas by diplomats and financiers. These are extreme

examples of how lack of legal status, especially combined with the restrictions

of being a live-in worker, can leave domestics at serious risk.

Says Carol Pier,

a Human Rights Watch researcher who has reported on special-visa domestics,

"Migrant domestic workers with or without visas are often isolated, devalued by

their employers, and invisible to government scrutiny." In immigration hubs like

New York,

they are believed to constitute a possible majority of the workforce.

Fear of

deportation, language barriers, and ignorance of U.S. laws keep undocumented

workers earning less and working longer hours, often at more physically

demanding jobs. The government offers them little relief, banning them even from

collecting food stamps, although they are covered under minimum wage and

overtime rules.

As a result, they

can end up earning "pennies," says Maurice Wingate, president of Best Domestic,

one of

Manhattan's

largest agencies, which does not place the undocumented. "I've heard of

situations where they just work for room and board. They end up taking what they

can get. They are subject to harsher violence and unfair treatment."

Says Carla

Vincent, a nanny who works here to support an eight-year-old daughter in

Trinidad, "parents really take advantage" of women like her. Her first job in

New York paid $225 per week in 1998 for live-in child care, housekeeping, and

cooking. "I would have to wait until they were finished eating and then eat.

Then she wanted me to meet her in the

Hamptons,

and I would be responsible for my own traveling expenses."

There are many

women in her situation, she says, "every second nanny that you meet. We give up

a lot, and it's only because you can better support your children from here than

if you were home. There are no jobs down there."

Even for those

without immigration worries, the fluid boundaries of domestic work can allow for

exploitation. Job titles and stated duties are often mere formalities. "Quite

frankly, some parents will place a job order saying they want a nanny, and

they'll kind of leave out the housekeeping aspect. They start with making the

beds, then it goes to sweeping the floors, then to mopping, then before you know

it, you've got a person doing nannying and housekeeping," says Wingate.

He says the

best-paid domestics can earn upwards of $800 a week. But the U.S. Department of

Labor, without data on undocumented workers, puts the median weekly wage for

family child care workers at $265, for a 35-hour week. In New York, that sum

would fall below the $5.15 hourly minimum, if a more typical 50-hour week and

overtime rules were factored in.

Even the worker

who enjoys above-minimal conditions should not rest easy, says Ann Campbell, a

nanny from

Grenada

with a job situation she calls "very rare." She nets $500 after taxes for an

approximately 40-hour week, strictly for live-out child care. Finding a decent

job, she says, "is based on luck, finding the right person to work for. It's not

based on how well you do your job. Even though I'm in a good situation now, you

never know."

The law does not

necessarily guarantee a decent job. Domestics are excluded from many basic labor

rights, including the right not to be fired for collective organizing. Laws

prohibiting discrimination based on race and sex usually apply only to

workplaces with multiple employees. While their history is complex, these

exclusions are essentially based in traditional notions of women's work and

servitude.

State and federal

labor agencies do not actively monitor household workers' conditions, although

all are entitled to their help in recovering minimum wage and overtime pay.

However, spokesman Robert Lillpopp says the state Department of Labor has no

record of how many domestics have actually sought such aid. A U.S. labor

official, speaking on background, says the department's New York City office

receives

six to 12 domestic worker wage and hour complaints a

year, most from third-party advocates.

"We do not get as

many complaints as we think we should," says the official. And when inspectors

follow up, he says, they find that "these are employers who are very difficult

to deal with. Trying to get it done without jeopardizing the individual's work

environment—making sure the employer doesn't take any kind of retaliatory

action—makes it difficult."

In New York City,

the Department of Consumer Affairs monitors the businesses that place an

estimated 50 percent of domestics. But spokesman John Radziejewski says labor

conditions are the Department of Labor's responsibility. If DOL were to notify

DCA of problems, he says, "we would take them under consideration." Lawyers

supporting the domestic workers group say, however, that DCA cannot absolve

itself of worker responsibility. The group hopes the pending reforms and a newly

vigilant City Council will spur more rigorous oversight.

Domestics can

file private lawsuits. But according to Ranjana Natarajan, who handles such

suits as a staff attorney at NYU's Immigrant Rights Law Clinic, no more than a

dozen such complaints were brought in the city over the past several years.

Lawsuits require that workers know their rights to begin with, she says, and

they can be intimidating, costly, and drawn out.

"So many

employers count on the fact that it's such a privatized industry," says

Natarajan. Collective action, she says, is key. "The biggest factor is that

workers feel secure and have some sense of support."

Among the few

dozen women gathered over potluck one late December night in Brooklyn, support

is all any of them can afford to give generously. Here, in a Fort Greene space

donated by a community organization, Domestic Workers United hosts parties,

nanny trainings, and reform planning sessions that have drawn several hundred

over the past few years.

Tonight, the

women are especially fired up. Someone brought a plastic pitcher of

sex-on-the-beach. And Campbell, the nanny from Grenada, shares a harrowing tale.

Her 5-foot-10 frame sways dramatically as she describes escaping from within

blocks of the collapsing World Trade Center with two toddlers and a stroller in

tow. Her audience gasps appropriately. "We have a real hero here tonight," says

one woman. Adds another, "See, her main concern was the kids. You can't put a

price on that."

For talk tonight

is of the low price most of them do get, especially now that times are tighter.

"To fire you, everybody's blaming the World Trade Center," says a woman who was

recently laid off. "Jobs are harder to come by," another chimes in. "If you can

find work, it might be for fewer hours."

One woman was

fired when her employers found out she was pregnant. It's a familiar story, one

that prompts sympathy and promises of a baby shower.

Another worker

was fired, even after working on Thanksgiving to serve a dinner for 17. When she

objected to working that day, she says her boss told her, "You are Jamaican, and

it is not your holiday." The group erupts. "We're in America, why isn't this

holiday being respected?" demands one woman. "Then give us all the Jamaican

holidays off!"

As in many

conversations among these nannies and housekeepers, reform becomes the central

topic. The women's stories make clear how isolation and lack of regulation leave

individuals with little recourse. The group wants a standard for the fair

employment of domestic workers, one recognized by both employers and officials,

so that it can function almost as an industry-wide contract. And in a

several-years-long campaign, they have attracted the numbers, advocates, and

official support they hope will help them achieve it.

"There are

probably not tons of domestic workers who can afford to live on the Upper West

Side," says Councilmember Brewer of her district. "I don't care. I'm very

committed." She frames the measures she is about to propose in the broader

context of women's and labor rights and plans to form a coalition to reflect

that scope. In fact, the workers already have the support of the AFL-CIO's

Central Labor Council and influential locals of the hotel and restaurant

workers' and service employees' unions. A slew of women's and minority groups

are also on board, as are prominent figures like Gloria Steinem.

A few of the

workers were fired when their bosses learned of the rights campaign. But several

showed their employers Domestic Workers United's suggested standards and

received support and, in a couple of cases, a raise. Parent Eddie Rosenstein

welcomes the idea of universal standards, saying, "I want things to be clear, so

they don't mistrust me, and I don't get scared I'll get gouged." Moreover, he

says, "As a decent employer, I'm getting the residual effect of bad employers,

who've abused overtime, who've cheaped out."

Indeed, council

proponents point out that the standards they are hoping to legislate essentially

reinforce bare minimums. Opposition, they say, would be difficult to defend.

Even if they

pass, the measures will still hardly revolutionize household employment. But the

stamp of official support is a great deal more than the workers have had to this

point. "I'm thrilled to be getting the City Council's backing," says organizer

de Leon. "To me, it's a weapon already" in the battle to define domestics as

workers with rights.

Special research:

Sophia Chang; research: Joshua LeSieur

"The Nanny Diaries" by Emma

McLaughlin and Nicola Kraus

Two real-life

nannies paint a wickedly funny portrait of their pampered charges -- and the

kids' even more spoiled and demanding parents.

By

Stephanie Zacharek

March 21, 2002 |

P.L. Travers, the author of the wonderful Mary Poppins books, remains the finest

practitioner of nanny lit. But with their tart, lively and genuinely openhearted

debut novel "The Nanny Diaries," Emma McLaughlin and Nicola Kraus, both former

nannies themselves, carry on Travers' esteemed tradition -- except you might say

that a Kate Spade tote replaces the old carpetbag.

And

unlike the Travers books, "The Nanny Diaries" is a sharply barbed comedy of

manners; the denizens of New York's Upper East Side (and, by extension, their

brethren in all other tony, overpriced, deadly dull neighborhoods in cities

around the world) are its target.

The

heroine is a 20-ish New York University student named (what else?) Nanny, who

has worked her way through college by taking care of rich people's kids. She

always enjoys the kids; the parents are another story. She meets her biggest

challenge when she takes on the job of looking after Grayer X, the 4-year-old

son of Mrs. X (a vacant, Prada-wearing socialite whose most meaningful activity

in life is that of turning condescension into an art form), and Mr. X (a

powerful investment banker who spends so little time with his son that he

probably couldn't pick him out of a crowded sandbox).

Grayer

is a spoiled pest when we first meet him, but Nanny -- who comes from a

well-educated, politically liberal, unsnobbish family, and who is working toward

a degree in child development -- has ways of winning him over, which mostly

involve listening to him, talking to him and simply treating him like a human

being, skills his parents can't be bothered to learn. In fact, it almost seems

as if Mrs. X considers it her chief responsibility to single-handedly make Nanny

miserable: She rings Nanny at home at ungodly hours; demands that she assemble

gift bags for her dinner parties and run personal errands she's too lazy to do

herself; and, worst of all, watches Nanny like a security guard at Harry

Winston, rebuking her for any number of imaginary missteps in her approach to

child care. (Mrs. X's favorite mode of communication consists of notes written

on expensive stationery that convey stern messages like "As a rule I don't like

Grayer to have too many carbohydrates" and "It has come to our attention that

after you left in such a hurry last night there was a puddle of urine found

beneath the small garbage can in Grayer's bathroom.")

The

irony, of course, is that Mrs. X isn't a bit interested in her child as anything

but an accessory. But in between shuttling Grayer from French lessons to piano

lessons and ice-skating lessons, not to mention to preschool and scheduled play

dates, Nanny grows fond of him and repeatedly makes an effort to "sell" Mrs. X

on him in a desperate attempt to improve his overscheduled-yet-empty little

life.

McLaughlin and Kraus keep "The Nanny Diaries" funny and light, but they're also

good liberals at heart: Nanny befriends a fellow nanny in her early 40s who used

to be an engineer in her native San Salvador but who can find only low-paying

child-care jobs in the United States. Nanny is also keenly aware of the fact

that many of her fellow nannies have young families of their own, families that

are often left to the care of grandparents while the nannies tend to the little

pashas of the Upper East Side. (McLaughlin and Kraus perfectly capture the

flavor of those pampered lives, as perceived by the nannies, in one very short

passage: "We push our charges over to Fifth Avenue. Like little old men in

wheelchairs, they relax back in their seats, look about and occasionally

converse. 'My Power Ranger has a subatomic machine gun and can cut your Power

Ranger's head off.'")

McLaughlin and Kraus are largely sympathetic to the children (who can't, after

all, be blamed for the sins of their clueless parents), but they spare little

mercy for monster moms and dads like Mr. and Mrs. X. They describe a special

paddling "spatula" move that Mrs. X uses to deflect Grayer whenever he rushes up

to attempt a hug (she wouldn't want the Gucci mussed). And while Mrs. X is

capable of occasional vulnerability and even kindness (she does give Nanny a

pair of cast-off Prada pumps), her generosity is really about as deep as a

Tiffany's thimble. At Christmas, she bestows expensive handbags and large checks

on her other servants, while reserving a special insult of a gift for Nanny: a

pair of earmuffs.

"The

Nanny Diaries" has caused something of a stir on Manhattan's Upper East Side,

some of whose citizens have taken great pains to point out that the book is most

certainly not about them. Some people are incredibly angry: According to an

article in the New York Times, the inhabitant of one building wants its board to

pass a rule preventing anyone from writing about its tenants. (That'll learn 'em!)

But

despite the fact that McLaughlin and Kraus have both worked as nannies, it's

clear that "The Nanny Diaries" is a work of fiction. The characters are too

broad and exaggerated and wincingly funny to be 100 percent true to life. But

then again, some people don't know the meaning of "satire." It's so hard to find

a good-looking dictionary that doesn't clash with the color scheme of the

library.

Mary Poppins with

attitude

(Filed: 24/02/2002)

The uniform may have gone, but

nanny still reigns supreme in this novel, finds Jane Shilling

Say the word "nanny" to an

Englishman of a certain age and class and his lower lip will begin to tremble.

His daddy may have been rich, and his mama good looking, but nanny was the one

who came to hush him when he cried.

Unsurprisingly, English literature

is full of nannies - cherished, if slightly alarming figures with a trenchant

turn of phrase and a comforting smell of ironing. Such figures seem to belong to

a vanished past - a time of footmen and under-house parlour-maids. But while

even the grandest establishments these days are pretty light on footmen, the

nanny lives on. Her uniform may be Gap chinos and a fleece, but her domestic

dominance is equal to that of Mary Poppins herself.

The Nanny Diaries is a

novel by two former nannies, Emma McLaughlin and Nicola Kraus. Kraus and

McLaughlin are American; Central Park, rather than Kensington Gardens, is the

territory of their nanny heroine who is clumsily (or "aptly", as their publicity

has it) named Nan.

There are other points of

divergence between this latter-day Poppins and the original. Gone, for a start,

is the wary choreography of mutual respect that traditionally defined relations

between the nursery and the rest of the household. In The Nanny Diaries, the

predominant emotion is dislike. Nanny loathes her employers, Mrs and Mrs X, who

treat her like a slave (Mrs X), or haven't the faintest idea who she is (Mr X).

Mr X is also a touch vague about

the identity of his son, whom he barely sees, thanks to his pressing work

commitments. Particularly pressing is the luscious manager of his Chicago

office, with whom he is obliged to hold a great many essential meetings.

Nanny, meanwhile, is supposed to

mitigate the effects of his parents' marital froideur on four-year-old Grayer,

between whisking the child from French class to piano lessons, to playdates, all

the while making sure that he eats strictly organic and doesn't touch his mother

when she is dressed up ready to go out. This, incidentally, is supposed to be a

part-time job, to pay Nanny's way though a degree in Child Development at NYU.

The novel is very funny, but there

is an ominous ring of authenticity to the comedy, which may perhaps be even more

revealing than the authors intended. The Xes are undoubtedly figures of inspired

monstrosity. But then Nan herself is, like so many fictional nannies, a highly

ambiguous character with an insistent need to bewitch the child and a strong

streak of the victim in her makeup.

For a frothy little satire, The

Nanny Diaries has an unexpectedly bitter aftertaste.

The Star Online

Friday,

March 8, 2002

Poor little rich kids

The Nanny Diaries promises

to embarrass New York’s moneyed classes with a below-stairs expose of their

failings as mummies and daddies, writes ZOE HELLER.

THE

Nanny Diaries, published next month, is a novel about workaholic fathers

obsessed with work and totty, and self-indulgent mothers who fill their

children’s schedules with kung fu and feng shui, but who miss the school

plays. The authors, Emma McLaughlin and Nicola Kraus, are two young women who

nannied for several years to pay their expenses while studying at New York

University.

The idea

for the book came to McLaughlin in 1999. She met a publisher at a party,

explained the concept and shortly afterwards she and Kraus landed an advance of

US$25,000 (RM95,000).

They have

since sold the film rights to their novel for US$500,000 (RM1.9mil) and both

women are now actively pursuing careers as full-time writers. The principal

characters of their story, an Upper East Side power couple called Mr and Mrs X,

are said to be a composite of some of their various, former, real-life

employers. Mr X is rich, attractive but cold. Ditto Mrs X. The Xs’ child is

rich, attractive, but woefully neglected, hence, angry, lonely and confused.

The

promotion for The Nanny Diaries would seem to place it in the

time-honoured tradition of servant’s revenge stories, whereby the put-upon help

get their own back by revealing embarrassing details of the employer’s domestic

life. There is a devastating tell-all to be written about the exploitative

employment practices that are rife in the world of nannying.

But that

would have to be written by a Jamaican woman with three kids in Queens and no

green card. McLaughlin and Kraus, both of whom are white, educated and quite

posh (one of them is a graduate of the exclusive New York private school

Chapin), do not seem to have experienced the genuine servitude that many

non-white, non-American nannies endure, and their bad memories have less to do

with economic injustice and snobbery than with the poor parenting of some of

their former employers. They’re a bit miffed about the time the lady of the

house tried to palm one of them off with her old designer shoes. But mostly,

they’re sad, in a rather pious way, for the kiddies.

In a

recent interview in the New York Times, they explained how traumatised

they were when they first started caring for over-privileged, under-loved

children. “It was existentially stunning,’’ McLaughlin said, “beginning our

lives as young women and saying, ‘Okay, so this is what a lot of money and doing

everything right has left you?’ The absence of warmth, the absence of real

intimacy. It was such a cold state.’’

It’s

always cheering to discover that the rich are cold and snotty and deeply

unhappy. But I have to say, as a nanny-employer and an averagely flawed mother,

the thought of this book does rather strike dread in my heart. In the United

States, where to be “non-judgmental’’ is regarded as a noble aspiration, the one

area in which everyone seems to feel absolutely free to judge is parent

behaviour. I realise I am not meant to identify with nasty old Mr and Mrs X. On

the contrary, their awfulness as parents, is meant to make me feel better about

myself. But something about these women providing their beady-eyed take on the

selfishness of some of their former employers makes me defensive.

The world

is always looking to find a new way to beat up on imperfect parents –

particularly the female ones and Kraus and McLaughlin, I fear, have, quite

unintentionally, provided another stick.

It’s not

the socialite ice queens presiding over loveless Upper East Side households who

will recognise themselves in this book. No, it’s the already-harried working

mothers who will clench their buttocks, as they wonder guiltily whether they

have been spending enough time pretending to enjoy Lego with their children and

whether the Christmas present they gave the babysitter last year was

sufficiently generous.

Reading

McLaughlin and Kraus bang on about the parlous state of Manhattan parenthood, I

can’t help wondering what my babysitter would write about me, if she were

offered US$25,000 (RM95,000) to do so.

No doubt

she would want to point out how poor my time-management skills are; that I am

always neglecting to purchase loo paper; and that there is an almost-constant

ring around my bath. She would point out that in moments of weakness, I have

been known to blackmail my daughter into giving me a kiss by pretending to cry

and saying, “Mummy is sad’’.

She might

also want to include the fact that, because my boyfriend and I were heavy

smokers when my daughter was first learning to speak, her default word (and the

name of her imaginary friend) is “Ciggy’’. (I always tell people that she’s

saying “Sigi’’, but the babysitter knows the dark truth.)

She’d

almost certainly want to divulge the fact that my daughter survives on a diet of

fish fingers and bright green corn puffs called Veggy Booty. (I used to feel