12-11-2002

SAVING

VENICE

|

Venezia,

città di gondole, di storia, di arte, di stile... chi non desidera andare in

questa città italiana quasi fiabesca? Eppure, mentre si è a Venezia o si

pensa di andarci, pochi si preoccupano dei problemi relativi alla sua

salvezza.

Si sa già che Venezia è costruita su 117 isole, il cui

terreno presenta il pericolo di sprofondamento. Effettivamente con

il passare degli anni, il livello dell'acqua è salito notevolmente e

continua a salire anche a livelli allarmanti. Diversi anni fa, lo Stato ha ideato

un progetto di salvaguardia per Venezia e la sua laguna,

e ha anche iniziato a implementarlo, investendo ingenti somme di

denaro. Ma Venezia è ancora in balia dell'acqua alta, che sembra

aumentare regolarmente ogni anno di circa 0,5 - 1 mm.

|

|

|

|

La salvezza della Serenissima non concerne soltanto l'aspetto

geografico, ma anche quello socio-culturale. Si dice che Venezia abbia vissuto

il suo momento d'oro durante gli anni '50, quando era affollata di

pittori e artisti, ed era animata da una vita propria che esisteva aldilà

del turismo. Purtroppo, la situazione attuale è ben diversa. Oggi, si teme che

a Venezia tocchi inevitabilmente un destino che la farà diventare una

città simile a Pompei, ovvero una città-museo. Mentre i turisti aumentano, i

veri veneziani sono sempre di meno e i giovani sembrano essere più attratti

dalla vita che si svolge nei grandi centri veneti come Padova, Treviso, Verona

ecc.

Tuttavia, in questo clima d'indifferenza e di rassegnazione

vi è anche e sempre un pizzico di ottimismo, ottimismo che a volte sembra ispirare

esperti a escogitare alternative a un destino altrimenti

ineluttabile. Ma quale sarà il destino della famosa

Venezia nel terzo millennio? Non perdetevi il prossimo numero del Gazzettino

dedicato al segreto della salvezza di questa città unica al mondo.

Nella prima parte dedicata a questa magica città, si è concluso

che Venezia si trova senz'altro in una situazione precaria. Ma "salvarla"

che cosa significa? Fine ultimo del salvare Venezia sarebbe quello

di ridarle vita, di ristabilire il legame con la terraferma. Ci

sono stati vari tentativi proprio per non escludere Venezia dalla vita moderna

(per esempio, la linea ferroviaria, il ponte automobilistico, la

mostra cinematografica, ecc.), eppure, è scattato ugualmente

l'allarme!

Uno dei

pericoli principali è in realtà costituito proprio dal turismo. Pur avendo

favorito l'economia della città, il boom turistico si è sviluppato in modo

esagerato e di conseguenza ha contribuito all'elevatissimo costo della

vita a Venezia, tanto che i veneziani stessi sono fuggiti per

ritrovare altrove la quotidianità di una vita normale. Coloro che si

possono permettere il lusso di vivere a Venezia spesso non sono i

veneziani e appartengono a un ceto sociale molto benestante. La

situazione crea squilibri nella struttura sociale e fa sì che

predomini una monocultura basata quasi interamente sul turismo.

Una soluzione proposta di recente consisterebbe nel

collegare Venezia con la terraferma, costruendo una rete metropolitana

sublagunare. I collegamenti includerebbero Padova, Mestre, Treviso e varie

zone di Venezia stessa. Il costo del progetto sarebbe minimo visto che si tratta

semplicemente di appoggiare un tubo sul fondo della laguna e

costruire le varie stazioni secondo uno schema di circumnavigazione della

città. Il métro potrebbe diventare un collegamento più rapido ed

efficace, paragonabile alle fluide reti stradali nei grandi centri

urbani. Con il métro s'immagina un ritorno alla vivibilità per l'italiano

medio a Venezia. Non tutti però sono d'accordo e la questione ha suscitato

l'interesse di molti studiosi. Per chi desidera saperne di più anche per quel

ch'è il destino di Venezia nel terzo millennio, Il Gazzettino suggerisce

la lettura del libro di Gianfranco Bettin intitolato Dove volano i leoni.

Poison and

antidote

Nicholas Lezard on Paul

Morand's love affair with Venice and Régis Debray's polemic against falling in

love with the floating city

Saturday July 20, 2002

The Guardian

Venices, by Paul Morand,

trans Euan Cameron (Pushkin, £12)

Against

Venice, by Régis Debray (Pushkin, £9)

|

This week,

it is harder than usual to make a choice of one particular paperback: Pushkin

Press has wittily issued two books about Venice which are mortal enemies of each

other; and yet which go together as well as a rich meal and the sorbet which

cleanses the palate after it.

Paul

Morand's Venices is so lush that at times one imagines one is reading a parody.

This year-by-year collection of snapshots from his time in Venice contains the

kind of archness that you can imagine Cyril Connolly debunking: "When I ran away

for the first time, not yet 20 years old, I threw myself upon Italy as if on the

body of a woman." And yet... it can be like that, can't it?

Morand was

the all-round aesthete; that is, he could be picky not just about his art but

about the company he kept, as well as where he kept it. There are stories here,

many of them first-hand, about Diaghilev, Proust, Renoir père, d'Annunzio, Les

Six (there's a picture of them on page 110 which you can refer to whenever you

get stuck trying to remember their names), Paul Claudel ("who handed out

hard-boiled eggs, on which he had written poems, to each of us"), and a whole

host of now-obscure statesmen, poets, writers, diplomats, courtiers. And the

thread running through this is his love of Venice, his unending fascination with

the place, its constant yet mutable depravity, all recalled in 1970, at the age

of 82.

|

|

Click to enlarge |

|

And if you

can smell something sinister, something hinted at by remarks like "these Leicas,

these Zeiss; do people no longer have eyes?", you'd be right: for Morand served

in the Vichy government during the second world war, and even though he was

pardoned by De Gaulle in 1968 (and, having been elected to the Académie

Française, is now technically immortal), his last 30 years were marked by

bitterness and shame. You will note that while each chapter heading is a year,

there are no entries between 1938 and 1950.

Against

this very book - it is explicitly mentioned in the text - is Régis Debray's

Against Venice, written in 1995, and very ably translated by John Howe. Debray

may have been an adviser to Mitterrand, but he also fought with Che's guerrillas

in Bolivia, and was imprisoned there for three years. He can write brilliantly.

Why can't we produce anyone like him? Or even Morand? God, the British are dull.

Debray's

mischievous polemic denounces not only the modern tourist but the so-called

sophisticate for swooning over a Venice that is little more than a narcissistic

reflection of the viewer's own pretensions. "The Venetian idiot is not the

Venetian born and bred... He is the foreign noble who is obviously mad on

Venice, mad from nobility and by nature, since the passion for Venice has become

the statutory characteristics of Verdurins aspiring to be Guermantes..." He's

right, of course; and he's getting at the likes of Morand. "Why does Venice turn

the heads of French academicians? Two out of three of them go there to drink it

all in, noisily. As if it were part of the job." Debray is funny, hugely

intelligent, immensely quotable, and possibly quite insincere.

So, two

superb books about Venice, poison and antidote together. The bad news is that

together, they cost £21. This is a lot to ask for 320-odd small but perfectly

formed pages. Blame the chain booksellers, who cannot get their heads round

Pushkin books' unconventional format. But buy these if you possibly can.

Saving

Venice

by Don Barker

|

One of the most visited tourist centers in the world

is today threatened by the very element that makes it famous. The canals of

Venice can no longer hold back the rise of the tidal waters.

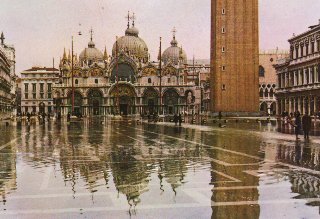

Of major architectural significance in the sinking

city and one of the lowest areas of the island is the

Piazza San Marco. The plaza now becomes fully immersed during the highest

tides of autumn and winter.

With high tides of more than a meter, the city

streets become blocked with water, and raised wooden walkways must be placed

along established pedestrian thoroughfares. In addition to disrupting the lives

of the inhabitants, the high water is causing considerable damage to their

architectural heritage.

|

|

Click to enlarge |

|

The Problem

Is Venice sinking? Or is the water level rising? The

answer is complex but "yes" to both questions. The mean level of the land has

lowered by 9 inches (23 centimeters) relative to sea level. Tapping the

underground water supply has caused a reduction in pressure in the subsoil and,

therefore, a contraction of the ground itself, with a subsequent lowering of

structures above.

At the same time, the tidal level has increased by

some 3 inches (8 centimeters) for several reasons, including organic structure

growth on the barrier reef in the lagoon basin and changes in atmospheric

pressure and wind action on the Adriatic Sea.

Eustasy, or the global variation in sea level, is

tied to changes in the world's climate. During the last century, the eustatic

rise for the city of Venice, independent of its subsidence, was on the average

0.05 inches (1.27 milimeter) per year.

The problem is significant and reflected in the

Italian government's declaration that the safeguarding of Venice is of "national

interest." The problem, however, does not belong to Venice in isolation; it

includes the surrounding lagoon and its complex interdependencies between

environment, architecture, and socioeconomics.

Invasions of the First Millennium

Why was a city built on a sedimentary island in a

lagoon off the coast of Italy? Blame Attila the Hun. During his invasion of

Italy in 452, the population of the countryside fled to the small islands of the

lagoons lining the western coast of the Adriatic.

Although many of the refugees returned to their

mainland homes after Attila's withdrawal, the seed was planted for the founding

of Venice. Many of the migrants remained on the islands such as Torcello, Burano

and Malamocco.

It was not until the assault on the settlements of

the Venetian lagoon in 810 by Pepin, the son of Charlemagne, that the

foundations were firmly laid. Pepin's forces easily seized land-based towns, but

his main aim was Malamocca island, the Venetian capital. The tidal channel

between Palestrina and Malamocco, however, ultimately proved too much of an

obstacle.

The lagoon's inhabitants decided to move the capital

to the more protected group of islands in the center of the lagoon. That area

was known as Rivo Alto, or "Ri'Alto" (high bank), because the islands were

sedimentary banks of the Brenta River delta, whose mouth lay several kilometers

to the west.

As the population grew, they expanded their island's

area dramatically by landfill behind rows of pilings. The area at Ri'Alto soon

became the metropolitan center of the lagoon, the city known today as Venice.

"Rialto" survives as the name of the commercial area that surrounds the oldest

bridge on the city's Grand Canal, which is itself the vestigial river bed of the

Brenta River.

Flooding of the 20th Century

The flood of 1966 was of symbolic importance. Venice

and the other historic towns and villages in the lagoon were submerged under

more than three feet (one meter) of water. Inspired by this disaster was the

initiative for a series of studies, experiments, projects, and remedial work.

The main parties were the Italian government,

responsible for physical safeguarding and restoration of the hydrogeological

balance in the lagoon; the Veneto Region, for pollution abatement; and the city

councils of Venice and Chioggia, for urban conservation, maintenance, and

activities aimed at promoting socioeconomic development.

Researchers from the mechanical engineering

department of Swansea University in Wales, UK provided computer models of the

rock strata, including joints, cracks, and faults. They have been instrumental

in understanding the cause of the subsidence problems.

Solutions for the Third Millennium

In broad terms there are two types of remedial work:

protecting the land mass and preventing the destructively high tidal movements.

Within this there are a number of initiatives for protecting coastal zones from

sea storms and restoring environmental balance to the ecosystem.

In the cities, towns, and villages in the lagoon and

along the coastline, local protection initiatives involve permanently "raising"

the lowest areas. However, concerns for historic architectural integrity and

entry-way accessibility limit such lifting to an agreed-upon 40 inches (100

centimeters). Therefore additional means are needed to control the highest tidal

waters.

It is widely accepted that modern boats contribute

partially to the general malaise in Venice's waterways. Agitation caused by

propellers and waves is undermining building foundations. Workers are finding

larger holes in buildings and quays. Canals are occasionally closed and pumped

dry to carry out remedial work.

There are three types of flooding: from water

breaking over the wall, filtering through subsoil, or overflowing from drains.

The plan provides a solution for all three types of flooding with solutions

appropriate to the delicate architectural and construction context.

To prevent flooding caused by filtration through the

subsoil without modifying the height of the square, a "horizontal defense

system" will be adopted involving the laying of a clayey compound membrane under

the paving in the public areas.

In addition to protecting public areas up to 40

inches (100 centimeters) above sea level, some private areas on the ground floor

below sea level will also be safeguarded against seepage. In some forty

properties, waterproof overflow tanks will be constructed, flooring will be

raised, and waterproof membranes will be installed as appropriate.

Land is also being protected from the erosive forces

of the sea by rock jetties that extend out to sea.

The Flood Barriers

One of the most ambitious projects is construction of

a high-water barrier, which will protect the whole lagoon from the sea.

The

Consorzio Venezia Nuova (Venice Water Authority) is responsible for

implementing measures to safeguard Venice and its lagoon. Its main task is the

construction of mobile flood barriers at the lagoon inlets, which will come into

operation when tides exceed 40 inches (100 centimeters).

The barriers' conceptual design was completed in

1989. In 1995 the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Boston produced

an environmental impact study of the design.

In 2001 the work on the design and planning continues

its path through politics, environmental objections, economics, and other

obstacles.

The mobile flood barriers will consist of box-shaped

metal flap-gates built into the inlet canal beds. In normal tide conditions they

are full of water and lie flat in their housings. A gate is 66 feet (20 meters)

wide and varies in height 66 to 98 feet (20 to 30 meters) and thickness 13 to 16

feet (4 to 5 meters) depending on the depth of the inlet.

The flap-gates are "mobile" because when tides exceed

40 inches (100 centimeters), an emission of compressed air empties them of water

and the unhinged edge rises. They temporarily isolate the lagoon from the sea,

blocking the flow of the tide.

The inlets remain closed for the duration of the high

water and for the time it takes to maneuver the flap-gates, a total of 4.5

hours.

The housing consists of prefabricated concrete

caissons which are inset in the lagoon floor and contain service tunnels and

machinery.

Eighteen flap-gates are required at the Chioggia

inlet and 20 at the Malamocco inlet. Because the Lido inlet is twice as wide, a

structure will be placed in the center of the entrance, with 20 gates to one

side and 21 to the other.

Once the go ahead is finally given, it will take

eight years to carry out the work at a cost of an estimated £2 billion.

The struggle to save this historic site continues

through localized remedial work against the rise of tidal waters and with a

groundbreaking engineering solution that has never been tried on this scale

before.

Don Barker is a freelance

writer and photographer in London, UK, who has lived and worked in Europe,

Australia, Thailand, Sri Lanka, Hong Kong, and Singapore.

Saving Venice

High

tech may hold back floods that are sinking famous Italian city. Find out more,

Thursday 3/28 at 9 p.m. Eastern on 'Tech Live.'

By

Bob Hirschfeld,

Tech Live

|

One of the

world's most beautiful cities is slowly sinking. Venice, the Italian city of

gondolas and canals, is in desperate need of a high tech repair job to keep its

priceless architecture from eroding. Tonight on "Tech Live" we take a look at

what's being done.

Along with the

scenic canals, exquisite works of art, and historic buildings, there's one other

thing that tourists often find in Venice: rain, which causes frequent flooding.

It's been a

problem in Venice

for centuries, and now it's taking its toll on the city's architecture.

An international

team of engineering experts is working with the Italian government on a unique

project to keep the Adriatic Sea from taking over the island city.

|

|

|

|

Damage toll

"It has a lot of

short-term damages. For example, tourism, and therefore, economy is affected,"

Chiang Mei, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, said. "In the long term, a lot of

architectural treasures are decaying because of the frequent flooding and salt

aggression."

Mei is one of the

international consultants brought in to help solve the problem.

The experts have

devised a unique solution: a series of floodgates across the three inlets just

outside the lagoon that surrounds Venice.

Hollow segments

The individual

segments are normally filled with water and lie out of sight at the bottom of

the sea.

"When a storm is

forecast, they would pump air into each one of these gates, which is a hollow

box, and so they would come up by buoyancy, and they would be inclined at about

a 45-degree angle," Mei said.

The planning has

been underway now for more than a decade, but there have been problems with

money, politics, and even the basic engineering involved.

"Against certain

waves," Mei said, "it's possible that the gates don't swing together. They swing

out of phase. And so there may be some gaps in between."

He laughed at the

obvious understatement, "This will possibly destroy or reduce the efficiency as

a dam."

Environmental

opposition

Some

environmentalists oppose the project, saying the floodgates will prevent

necessary "tidal flushing" by the lagoon and could damage fish farms in the

area.

But Mei is

confident all the problems can be straightened out in the next few years,

leading to another six or seven years of actual construction.

The final cost,

according to Mei, will probably be around $2.5 billion.

Originally posted March 28, 2002

“The barriers for Venice are indispensable”

Italy’s leading oceanographer and

climatologist Roberto Frassetto, says politicians are to blame for the delays

By Anna Somers Cocks

VENICE. It is thirty years since Roberto Frassetto

started working on how to protect Venice from the waters. He has been certain of

what should be the solution for almost as long, but has grown weary of talking

about it in Venice, where the whole issue has become bogged down in scepticism,

suspicion and short term politicking.

He will, however, ask people just to look at the scientific evidence rather than

leap for any of the woolly and often wild ideas in circulation about how to

protect the world’s loveliest city. For he is one of Italy’s most distinguished

oceanographers: ten years at Columbia University; from 1970 to 1982 director of

the Istituto per lo Studio della Dinamica delle Grandi Masse in Venice, which

was given the task by the Italian government to study the geology, physics,

technology and environment as they related to the protection of Venice; from

1982 he has worked on climate change and he is chairman of the Italian

Commission of the International Geosphere Biosphere Programme.

He has Italy’s highest medal for valour; as a young naval officer he took part

in the famously dangerous underwater raid on the British fleet in Malta in which

he and his companions rode what were essentially manned torpedoes, with

devastating results for the British ships. While many may have forgotten this

episode, his subsequent scientific career has been of a coherence and

single-mindedness that, in any country less cynical and sceptical than Italy, it

would guarantee him a respectful hearing. The Art Newspaper interviewed him on

the solution for Venice.

Dr Frassetto, there appears to be no political will to create the mobile

barriers that international experts believe essential to prevent the flooding.

Is it true that these barriers are indispensable?

We began in 1971 by calling upon all the greatest international engineers to

find out how to defend Venice from the seas. It emerged that a mobile barrier

was the most likely and effective solution. Thirty years later no one has come

up with a better idea except for that of raising the entire city!

So why have the barriers not been built?

This has been the dilemma of the last 30 years. We realised that the objections

came from the politicians. There is a fear that by closing them for 100-300

hours a year—and there are some 8,600 hours in a year—it would affect the

exchange of water between the sea and the lagoon, and that the lagoon would

become polluted.

As the Special Law for Venice says that the lagoon is inseparable from the

historic city, it is not possible to act on one part rather than the whole.

There was also opposition at first from the Port Authority which said that by

closing even 100-300 hours a year, this would damage the shipping trade. This

could be partly true, but only partly, because when there is a really high

water, the wind is in any case so strong that ships cannot enter the lagoon.

Have these objections been overcome?

I would hope so, but they continue to be brought up for political reasons, and

people don’t know how to respond to them.

What about the Valli da Pesca (fish farms) in the lagoon and the Canale dei

Petroliferi, the deep channel cut in the last century to allow the passage of

petrol tankers? The Green party say that these contribute decisively to the

flooding of Venice and that if they were reduced or removed, that the problem

would be largely solved.

They are wrong. Very precise studies have been done and there are all the

mathematical models and evidence which show that if you widen the Valli da Pesca

to allow the expansion of the water you may reduce flooding by one or two cm,

which would not begin to tackle the problem. As for taking the Canale dei

Petroliferi back to the shallow depth of past times, that is absurd. You cannot

put the clock back.

It seems that, from the scientific and technical points of view, the problem

of flooding can and has been faced. It is now a political problem. Who is

against the solution? It seems to be the Green party, and as they form part of

the coalitions in power both nationally and locally, the government cannot move.

You are asking me something about a sector of society which I refuse to

consider. Science is not compatible with politics and whoever introduces

politics into science is out of order. If the politicians ask us for scientific

evidence, we are ready and willing to provide it.

The long-term risk is the ongoing damage to its buildings. The other, immediate

risk is the socioeconomic damage. This is very important; every time there is a

flood, the shopkeepers and people living on the ground floor suffer

economically. And a consequence of the lack of investment by business in the

city is the exodus of the population; when I came to live here 30 years ago,

there were 130,000 inhabitants; now there are 65,000.

This recent flood reached 140cm above mean sea level. How great is the risk

of a flood such as the one in 1966, that reached 200cm?

First, I must point out that this recent flood could have been worse: both the

1966 flood and this one happened in a phase of neap tide, in which case the sea

level can be 20-30 cm lower than spring tide.

So we could easily see a repetition in our life time of the 1966 flood and much

worse. In fact, present climatological studies, which are beginning to give very

interesting results, show that there is no possibility of a diminution of the

frequency and intensity of atmospheric perturbation; rather, a tendency for it

to get worse, so the flooding will also get worse over the course of the

century.

If you were prime minister of Italy what would you do?

I would already have built the barriers.

If they are not built, will those politicians who have failed to act bear the

responsibility for what may happen in the future?

Absolutely. The gates are of course expensive, but all defences are expensive.

The gates that defend London, Hamburg, Holland and St Petersburg have all been

expensive, but they have all been built. Venice is lagging behind.

Perhaps people want further certainty where the scientific data is concerned—all

the possible consequences of such measures—but the data is available. It has

been considered by an international commission that in the end made only two

recommendations: more study of the effects of sea level rise in consequence of

climate change over the course of this century, and more work on improving the

forecasting of storm surges caused by strong winds.

Is there a final solution for the protection of Venice or will it always be

work in progress?

There will never be a final solution; the world is constantly evolving and so

one must always be adapting to it and bringing things up to date. And then there

will be the problem of maintaining the barriers and coordinating all the

protective systems. The solutions will change just as the risks continually

change.

VENICE: DUELS OVER TROUBLED WATERS

Piero

Piazzano, Italian journalist, editor in chief of the magazine Airone.

How

can the ecological balance of Venice be reconciled with the demands of industry?

Is the highly controversial construction of mobile floodgates the solution? The

decision will be made by 2001

|

The traveller to Venice should

arrive at the end of a summer’s afternoon to see the sun turn into a huge red

disk and swell until it casts the lagoon’s furthest islands in a fiery glow

before sinking into the sea. Then, when the last tourist has left Saint Mark’s

Square, Venice

once again becomes magical. In streets that are empty at last, the inhabitants

of the world’s most beautiful city open their doors, letting the few lingering

visitors catch a glimpse of a time-worn, history-laden monumental staircase, or

a hidden, tree-shaded garden where Giacomo Casanova may have awaited one of his

mistresses two and a half centuries ago. It is the moment when the souvenir shop

signs go dark and the Venetians’ windows light up. |

|

|

|

Each day, they are fewer and older. In 1951, about 175,000 people lived on one

of the 118 islands connected by 160 canals which form the historic centre of

Venice. In 1998, a mere 68,000 remained, and that figure will likely drop to

40,000 by 2005. If students are not counted—they are lodged by landlords who do

not declare them to avoid paying taxes—

residents under the age of 19 make up a tiny percentage of the population. The

average age, already 50 in 1998, continues

to rise.

The Venetians are leaving, and they are taking their institutions with them: the

Assicurazioni Generali insurance company, the daily newspaper Il Gazzettino, the

local Rai station (the State radio and television network) and the banks.

Tourists, who arrive en masse, fill the void: 10 million debarked in 1994 and 15

million are expected in 2005. The city of theatres, churches, convents,

monasteries, palaces and bordellos is turning into a huge eating place. From

1976 to 1991, the number of pizzerias, restaurants and hotels increased by 144

per cent.

Confronting the sea with picks and

shovels

Will Venice grow old and die like its

inhabitants? That is anybody’s guess: the truth is hard to come by in this

labyrinthine city. Venice is the city of “perhaps,” as unstable as the lagoon’s

ecological balance. It is impossible to imagine the city without its lagoon, an

uncertain space, neither land nor sea, whose very name expresses absence: lacuna

is Latin for “lack.” This precarious and provisional place emerged little by

little as the rivers, torrents and streams that flow across the plains on their

way to the Adriatic deposited millions of cubic metres of silt.

The lagoon is not part of the sea; it is separated from the Adriatic by 50

kilometres of sandbars that end with the mouths of the

Lido, Malamocco and

Chioggia ports. Every six

hours, the tides run through the bars, flowing in as salt water and receding as

briny water. Like a gigantic lung made up of thousands of bronchial tubes, the

lagoon breathes. It is not only formed by islands high enough to stand up to the

sea’s equinox tides. Barene, the sandbars that emerge at low tide, are complex

ecosystems, home to plants and animals which have adapted to this environment

oscillating between air and water. Velme are the mud-flats visible at low tide

while ghebi are channels that are green with mire and seaweed through which the

water leaves the lagoon at low tide.

The lagoon was bound to disappear until, one day, a group of bold men decided to

make something solid out of an unstable mass. Then, from one generation the

next, the Venetians battled the elements like funambulists walking a tight-rope.

Prepared with shovels and picks to confront the sea’s efforts to upset the

delicate equilibrium, they had only one thing in mind: to preserve the existence

and richness of Venice, the city of stone and marble that they built on spongy

marshland, as if it were on terra firma. Venice was a utopia: the world’s most

fragile city, but powerful enough to rule a far-flung empire.

Those stubborn people started by drying out the land, digging canals and

deviating rivers. For example, as part of a huge project begun in 1501 and

completed two centuries later, they changed the course of the lagoon’s three

main waterways: the Sile, the Piere and the Brenta. Then, and with increasing

frequency, they launched major public and private building projects to further

the civil and military development of the “most serene republic.” These projects

enabled merchant vessels and warships boasting the biggest drafts of their time

to enter the harbour or the Arsenal.

“Although with each project the technology became more aggressive than the

simple shovels and picks of the early days, these interventions have always

given the lagoon enough time to develop a new balance,” says Stefano Boato,

professor of city planning at the University of Venice. The same was true during

the operations carried out in the second half of the 19th century, when Venice

was definitively integrated into the

Kingdom of

Italy

(1866) after changing hands several times between

France

and Austria.

It was not until much later, between 1952 and 1969, that the city was dealt its

harshest blow. A straight, 15-metre deep canal was dug so that oil tankers could

berth at the industrial port of Marghera. At the same time, highly polluting

chemical and petrochemical plants were built across the lagoon, pumping more and

more water out of the aquifers and pouring more and more poison into the water.

“At that time, the delicate balance that had always existed, and that Venetians

had always managed to maintain over19 centuries of interacting with nature, was

broken. The situation is becoming alarming,” says Boato.

Aquatic highways for tankers and tourists

The lagoon, a unique ecosystem formed of fresh

water, brine and salt water, is inexorably turning into an arm of the sea in its

central portion and a swamp around the edges. During the time of the republic,

it was forbidden to dig canals more than four metres deep.Today, there are

veritable aquatic highways over 20 metres deep. Oil tankers, freighters and

powerful speedboats that can carry hundreds of tourists create waves that

destroy the sandbars and mud-flats, and cancel out the natural movements that

once slowed down the advancement of the tides.

All these disruptions increase the erosion that is ruining the depths of the

lagoon and eating away at the foundations of buildings. The Venezia Nuova

Consortium, a group of public and private companies which the Italian Public

Works Ministry and Venice’s Water Department have put in charge of carrying out

preservation work in the lagoon, says that 1.2 million cubic metres of soil are

washed away each year, while the province of Venice puts the figure at four

million. The mussel fishermen who “work” the floor of the lagoon using a fishing

method that is outlawed but tolerated also contribute to the erosion.

To make matters worse, fishing zones surrounded by dikes limit the tides’ area

of expansion. Twenty years (1950-1970) of pumping subterranean water lowered the

city’s ground level by 10 centimetres. Lastly, the Adriatic is rising, worsening

the floods to which the city and the surrounding area fall victim.

As a result, in 1990

Venice

was 23 centimetres lower than in 1908. Furthermore, between 1965 and 1995, the

Venetians “forgot” to clean the city’s canals, a practice that their ancestors

considered indispensable for reasons both physical (to improve the circulation

of tidewater) and hygienic (to wash out accumulated waste).

The neglect has proven costly. On the one hand, Venice is beleaguered by over 50

days a year of acqua alta (“high water”), which floods many of the streets and

squares. On the other, with increasing frequency the tides are so low that

vessels can no longer sail on the canals.

Hard work for meagre results

On November 4, 1966, a gigantic acqua alta

entirely submerged Venice and the lagoon’s islands for 24 hours, causing

tremendous damage to the city’s economy and art works, and sending a wave of

panic around the world. If the water had risen a little higher, the world’s most

beautiful city might have been lost. And the flooding could reoccur at any time!

The shock triggered countless initiatives: Italian and international commissions

were set up, studies conducted, laws passed and projects proposed. Major

international bodies went on the alert, UNESCO

chief among them. The organization moved its office for science and technology

in Europe to Venice and undertook the grandiose “Project Venice,” an initiative

that has given rise to a profusion of studies and meetings to pore over all the

problems of the city and its lagoon: geology and morphology, the water’s

dynamics, chemical and biological processes, contamination, demographics,

traffic and cleaning up the canals.

No other city in the world has been studied in such detail. None has been so

painstakingly dissected to determine the reasons for its rise and fall. And, it

must be added, never has so much hard work produced such meagre results.

All things considered, and at the risk of oversimplifying, this complicated

business can be summed up in two sentences. They are written in bureaucratic

jargon in law 798, the most important piece of legislation concerning Venice

passed since the 1966 flood. The first sentence says that the work to save

Venice must “restore the hydrogeological equilibrium of the lagoon, slow down

and reverse the process of degradation and eliminate its causes.”

In other words, everything must be done to clean up the canals and to restore

their depth to acceptable levels (other laws specify 12 metres), to re-open the

fishing lagoons, and to recreate the sandbars and mud-flats. But a

harmless-sounding sentence in the same law specifies that all these operations

must be carried out while “preserving the area’s productive and economic

interests.”

In other words, the bottoms of the canals must be raised but oil tankers must

not be prevented from travelling through them, the size of the lagoon’s harbours

must be reduced but the current level of traffic must be maintained, the tidal

swells must be contained but vessels must be allowed to continue carrying swarms

of tourists to the islands of Torcello and Murano. The law’s authors seem to be

the direct heirs to the playwright Carlo Goldoni and his Harlequin who served

two masters.

The system of mobile dikes and floodgates planned as a solution has been a bone

of contention for nearly 20 years, setting off many debates and discussions

between engineers and politicians. It is called Mose, the Italian name for Moses

and an acronym that stands for Modulo Sperimentale Elettromeccanico, a prototype

floodgate that was tested in the Treporti canal between 1988 and 1992. After

years of studies and numerous variations, Project Moses was adopted by the

Venezia Nuova Consortium. The plan is to equip the entrances of the Lido,

Chioggia and Malamocco ports with a system of mobile floodgates: chests that are

20 metres wide, 20 to 30 metres high and four to five metres deep.

In normal conditions and as long as the tide’s amplitude does not exceed one

metre, the water-filled chests will lie on the floor of the canal. When the tide

is dubbed “exceptional” (an average of seven a year and 20 in 1996), a hydraulic

system will fill the chests with air to raise them. Since the chests are

connected to the canal’s floor with stakes driven into the mud, they work by

rising like a gate that closes, becoming dikes that cut the lagoon off from the

sea. Under the plan, 18 floodgates will be set up at the entrance to the port of

Chioggia, 20 at Malamocco and two sets of 20 and 21 separated by an intermediate

harbour basin at the entrance to the Lido.

Furor over floodgates

According to estimates, this

enormous task will require eight years, 6,000 workers and 3,700 billion lire

(approximately $1.8 billion). The city of Venice puts the project’s total cost

at 5,334 billion lire (in 1992 prices), or some $2.6 billion—not including

maintenance.

“These mobile dikes must be built,” affirms Philippe Bourdeau, a professor at

Brussels’ Free University and chairman of the international committee of experts

named by the Italian government to evaluate the project. “The mobile

floodgates,” he says, “are, along with raising the ground level and the other

planned measures, the best way to save Venice for the next 100 years.”

“These mobile dikes must be absolutely avoided,” replies Stefano Boato, along

with the Green Party, the Italia Nostra environmental group, Greenpeace, the

World Wildlife Fund for Nature (WWF) and other environmental organizations,

which say that the project would have a disastrous effect on the fragile

ecosystem. But the municipality

of Venice, together with the Environment and Cultural Heritage ministries, are

leading the camp of those invoking the precautionary principle. They argue that

the lagoon’s geomorphological, hydraulic and biological balance must be

restored—for example, by cleaning up the canals, which began in 1998 (see box),

and raising the ground level—before any decisions about the mobile dikes are

made.

In addition to this controversy, other questions have arisen. For example, the

city’s autonomy is at stake. The Department of Water, which depends on the

Public Works Ministry in Rome, and the companies that make up the Consortium,

which include major public and private corporations (such as Fiat), have few or

no ties with Venice, whose population has been accustomed to solving its

problems alone for 2,000 years.

Fear of oil spills

And then there is the economic aspect: $2.6

billion, a sum that rises with each passing day, is a tremendous amount of

money. If all of it is allocated to a single project, what will be left for

other initiatives and for the small Venetian companies that could carry them

out? When all is said and done, the big corporations in Milan, Turin and Rome

would reap the benefits and Venice would have to settle for the crumbs.

The debate has been raging for a long time. In November 1998, the project’s

environmental impact commission, appointed by the Environment Ministry and

chaired by Maria Rosa Vittadini, an architecture professor at the University of

Venice, issued a negative assessment and requested the Consortium to review the

entire project. One month later, a ministerial commission published a similar

review, which was annulled in June 2000 by the regional administrative tribunal

of the

Veneto. The latest news is that, during a meeting of experts held

in Rome in July 2000,

Prime Minister Giuliano Amato said the final decision would lie with his office

and that it would be made at a cabinet meeting by the end of the year.

But what if Venice’s

real problems is not the exceptional tide, such as the one that struck the city

in 1966? And what if the next disaster comes not from the lagoon but from the

sea? Each year, 25 million tons of freight is shipped on the lagoon, half of

which is oil and petroleum products. A single oil tanker accident would be

enough to cause incalculable damage to the ecosystem, cover the canals with a

thick coat of petroleum and leave greasy, viscous streaks on the foundations of

palaces and churches forever. On November 29, 1995, five tons of light fuel

spilled into the lagoon, forming a huge slick that drifted for four days. Was

that a warning?

In the city of masks, the fiery glow of the beautiful red sunsets over the

city’s palaces and churches, which enchant tourists the year round, may not be

solely the gift of nature. That extra shade of red may well come from air

pollution arising from Marghera’s petrochemical facilities.

Pierre Lasserre and Angelo

Mazollo (eds.), The

Venice Lagoon Ecosystem,

UNESCO Publishing/Parthenon, 2000.

Venice is Sinking & Italy is Watching so Why Should the US

Help?

by Melissa Fien

Venice is no doubt a cultural treasure, but

without initiative on the part of the Italians to preserve the city, how much

can the US really do? The harsh reality is: Venice is going to sink - and unless

Italy takes more action - there is nothing anyone else can do about it. The law

recognizes this unfortunate reality and therefore, requires the New York

Attorney General to ban fundraising to save Venice until Italy has established a

long-term plan for the city’s protection.

No Amount of Money Can Save Venice: The History

and Future of Venice’s Flooding

The water which makes Venice the most majestic city in the

world now threatens the city’s very existence. On November 4 1966, a flood hit

Venice so hard that Venetians every day since have lived in terror for the next

big flood. And, Venice does continue to flood. St. Mark’s Square and other areas

of the city were flooded 101 times in 1996 and 79 times in 1997.1

Then, on November 6, 2000

Venice

experienced the third worst flood since 1900 with ninety-three percent of the

city being covered in water. Experts say that it is no longer a matter of

whether Venice will flood , but simply when the flooding will occur.2

The "acqua alta" - the high waters that cause the flooding - are here to stay.

And to make matters worse, the sea levels are rising. The combination of these

factors will inevitably lead to the sinking of Venice.

For a number of years, Italy has been posing a system of

mobile dykes and floodgates called MOSE as a solution. However, even Venice

officials themselves do not believe that MOSE will actually provide a long-term

solution.3

Global warming means that the floodgates will eventually be up almost all of the

time, ultimately sealing the city from the sea. While a decision regarding the

MOSE gates will be made in the next year, many doubt that MOSE will actually

save Venice from sinking. Therefore, at the moment Venice is inevitably doomed.

The Law Requires the New York Attorney General to

Ban Fundraising to Venice

Both United States and international law dictate

that the New York Attorney General should ban fundraising to Venice until a

long-term plan for the city’s protection has been established. First, the UN

places the responsibility of saving Venice on Italy, not the United States.

Second, Article 7-A of the Executive Law, Solicitation and Collection of Funds

for Charitable Purposes instructs the New York Attorney General’s Charities

Bureau to ban fundraising to Venice.

Italy’s Responsibility: If Italy Won’t Save

Itself From Sinking, Why Should the US?

First, the UN places the responsibility of saving

Venice on Italy, not the United States. Until Italy takes responsibility,

international assistance (including assistance by the United States) is not

warranted. Italy is the only one who can establish and implement a long-term

plan. So, without action by Italy, assistance by the US is meaningless.

Article 4 of the Convention Concerning the Protection of

the World Cultural and Natural Heritage states that the legal duty to establish

a long-term plan rests with Italy.4

Italy is the only one with the power to develop a long-term plan. Yet, Italy has

failed to fulfill its duty under Article 4. Italy has failed to file a request

to have Venice included on the World Heritage List in Danger.5

Since Venice is part of Italy’s territory, Italy must be the one to place Venice

on the endangered list. If Venice had been included on this list, Italy would

also have been able to request emergency financial assistance. However, because

Italy only placed Venice and its lagoon as a common entry on the World Heritage

List, UNESCO and the World Heritage Committee are limited in the actions they

can take on behalf of Venice. They cannot make Venice a priority because Italy

has not made Venice a priority. In addition, Italy neglected to use its

influence and power to get UNESCO to pay more immediate attention to Venice.

Until 1999, one of the vice-chairpersons of the World Heritage Culture was

Italian, and consequently, Italy had a key position in the Bureau of WHC.6

Furthermore, the Italians could have put Venice on the urgent agenda of the

International Center of Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural

Property (ICCROM). ICCROM collects, studies, and circulates reports about the

scientific and technical problems of the preservation and restoration of

cultural property. Since Italy has neglected to satisfy its obligations under

Article 4, outside assistance will do very little to help the situation.

Outside assistance on the part of the United States will

continue to be meaningless until Italy establishes a long-term plan. However, it

is unlikely that Italy will establish a long-term solution for three reasons.

First, special law no. 798 of 1984 makes the implementation of a long-term plan

nearly impossible. Law 798 requires that the city and the lagoon both be helped

simultaneously.7

However, most efforts to save the city tend to hurt the lagoon and vice versa.

Therefore, a long-term plan becomes implausible. Second, even Italy’s leading

oceanographer and climatologist Roberto Frassetto, admits that there will never

be a final solution for the protection of Venice.8

However, Venice no longer has the time for a "work in progress." If there will

never be a final solution, Venice will sink no matter how much money is placed

into trying to save it. Third, Italian politics make it difficult to implement a

long-term plan. Italian politics is a "cat’s cradle of coalitions" at the state,

regional, and city level. The Italian government has changed hands more than

twenty times, and with each the change, the government’s priorities change as

well.9

The prime minister and the mayor of Venice both depend on the Green party for

support. The Green party rejected project Moses because of environmental

concerns, and they will continue to reject any future proposals that do not

account for the environment and the lagoon. The Green’s party rejection of the

Moses plan has divided Venice, thereby making the implementation of a long-term

plan even less likely. The chances that Italy will establish a long-term plan

that can save Venice are extremely slim. Therefore, any money spent on trying to

save money might as well just be thrown into the sea.

Italy’s Swindling Money from the United States:

The Fraud and Deceit Must Stop

Second, United States law requires the New York Attorney

General’s Charities Bureau to ban fundraising to Venice until a long-term plan

is established. Italy does not have a long-term plan currently and will most

likely not have a long-term plan in the future. By soliciting charitable

contributions without a long-term plan for the city’s protection, Italy is

engaging in a fraudulent act in violation of Article 7-A. Article 7-A states:

"no person shall engage in any fraudulent or illegal acts, device, scheme,

artifice to defraud or for obtaining money or property by means of a false

pretense, representation, or promise, transaction or enterprise in connection

with any solicitation for charitable purposes."10

The term fraud includes acts which may be characterized as misleading or

deceptive. To establish fraud, neither intent to defraud nor injury need to be

shown. So, even though Italy might intend to use the charitable contributions to

help save Venice,

Italy’s intentions are irrelevant. The fact that

Italy is taking efforts to save Venice does not

overcome the fact that Italy is defrauding donors by making a false promise.

Italy is promising that the money donors contribute will help save Venice when

unfortunately, this money will not help Venice. Furthermore, since the

advertising used to seek charitable contributions says that the money will save

Venice from sinking, any advertisements used to solicit funds are in further

violation of Article 7-A. Absent a long-term plan, all the money in the world

could be put towards saving Venice, and Venice would still sink. Italy is

deceiving US citizens by allowing them to contribute to a hopeless cause. And,

until Italy establishes a long-term plan for Italy’s protection, Italy will

continue to mislead the US. The New York Attorney General, therefore, has an

obligation under US law to prevent Italy’s fraudulent behavior by banning all

fundraising to Venice until Italy can fulfill its promise that the charitable

contributions will actually help save Venice.

Notes:

1.

See Ellen Knickmeyer, "Saving Sinking Venice,"

http://www/abcnews.com/sections/travel/DailyNews/venice981202.html

2.

See Anna Somers Cocks, "The ecological dangers of Venice are not

being faced, say chairman of Venice in peril,"

http://www.theartsnewspapers.com/news.article.asp?idart=1292

3.

See Ellen Knickmeyer, "Saving Sinking Venice,"

http://www.abcnews.go.com/sections/travel/DailyNews/venice981202.html

4.

See Krassimira J. Zourkova, "Saving Venice: The Practical

Implications of the Law on Cultural Heritage Preservation" 15.

5.

See Id.

6.

See Id at 12.

7.

See Piero Piazzano, "Venice: Duels Over Troubled Waters,"

http://www.unesco.org./courier/2000_09/uk/planet.htm

8.

See Anna Somers Cocks, "The barriers for Venice are

indispensable,"

http://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/article.asp?idart=3950

9.

See Krassimira J. Zourkova, "Saving Venice: The Practical

Implications of the Laws on Cultural Heritage Preservation" 5

10.

Article 7-A of the Executive Law Solicitation and Collection of Funds for

Charitable Purposes As Amended through the Laws of 1997 §172-d.

Links:

La verità su Venezia

Acqua

alta

Esodo da

Venezia

Il

degrado di Venezia

|

Venezia:

Venice

(Venezia,

capoluogo del Veneto, situata al centro della laguna veneta, ha una popolazione

di 337 670 abitanti.

(Il Veneto

è una regione del nordest d'Italia. Confina a nord con l'Austria, a nordest

con il

Friuli-Venezia Giulia,

a sud con l'Emilia-Romagna, a ovest con la

Lombardia,

a nordovest con il Trentino Alto-Adige e si affaccia al sudest sul mare

Adriatico. Il territorio è diviso in pianure, zone montuose, una fascia

collinare e una fascia costiera [interamente bordata di lagune e paludi].

I fiumi sono numerosi [direttamente tributari dell'Adriactico], i più famosi

sono l'Adige, il Brenta, la Livenza e il Piave. Venezia, poi, è composta da 117

isole, tra loro collegate da oltre 400 ponti. Il Veneto ha una superficie di 18

364 kmq con una popolazione di 4 366 244 ab. Il capoluogo di regione è Venezia

ed è suddivisa in 6 altre province: Belluno, Padova, Rovigo, Treviso, Verona,

Vicenza.

L'agricoltura constituisce il fulcro dell'economia veneta e il turisimo a

Venezia è sempre stato di notevole importanza economica. Anche la pesca è attiva

nella zona di Chioggia. I complessi industriali di Mestre e Porto Marghera

meritano un cenno particolare.

Il Veneto ha una maggiore industria caseificia e produce vini squisitissimi [il

più comune è il Valpolicella].

|

|

|

|

Breve storia di Venezia

1. LINEE DI

STORIA VENEZIANA:

NASCE UNO STATO TRA TERRA E MARE

Chiamata

Venetia la "X Regio" nell'Impero Romano era costituita grosso modo dai

territori che oggi conosciamo come Veneto,

Friuli,

Trentino e Istria. Il confine meridionale era rappresentato dal mare Adriatico:

un'ampia zona soggetta a progressivi mutamenti orografici, con fiumi di ampia

portata che, combinando la loro azione con quella dei flutti marini, davano

origine a un ambiente di tipo paludoso, con numerose lagune. Si trattava di un

ecosistema "dinamico", una sorta di "via di mezzo" fra l'ambiente

dell'entroterra, relativamente stabile, e quello marino.

Questa zona, che

faceva parte della terra dei Veneti, assimilati all'Impero, era in epoca romana,

abitata da pescatori, "salinari" (addetti, cioè, alle saline), tutti esperti

nell'arte di costruire e manovrare imbarcazioni adatte all'ambiente lagunare e

fluviale. La stessa zona, tra l'altro, forse per la sua "tranquillità", era

usata come "luogo di villeggiatura" dai ricchi abitanti delle vicine città

romane (come Padova, Altino, Aquileia).

Col progressivo

disgregarsi dell'Impero e con invasioni dei popoli germanici, in particolare nel

VI secolo, le zone lagunari finirono coll'offrire un rifugio a quanti vedevano

le loro terre e i loro beni in balia degli invasori: avventurarsi via fiumi e

canali non era facile, per chi non conosceva la zona, e i lidi sabbiosi

costituivano un'ottima protezione da un eventuale attacco (dal mare). Fu in

particolare, l'attuale laguna di Venezia a vedere crescere maggiormente la sua

popolazione. Naturalmente questo significò anche un profondo mutamento della

composizione sociale nel territorio lagunare: molti profughi erano benestanti o

proprietari terrieri o allevatori delle città dell'entroterra, come Altino e

Oderzo. I primi centri che si vennero a creare furono Malamocco (su un lido),

Torcello (un'isola allo sbocco del fiume Sile) e un altro gruppo di isole al

centro della laguna, la futura Venezia.

Se l'entroterra

era in mano alle popolazioni germaniche, le lagune restarono, invece,

nell'orbita latina, come parte dell'Impero d'Oriente, dipendendo direttamente da

Ravenna. Fin dall'inizio, dunque, si stabilisce un profondo legame col mondo

bizantino. Alla fine del VII secolo gli abitanti delle lagune non erano più

governati dai "tribuni marittimi", i comandanti militari bizantini, ma avevano

un comando autonomo sotto un "dux", da cui il termine "doge". Nasce in tal modo

la prima forma di stato veneziano (seppur legato a Bisanzio): il "Dogado".

Verso l'810 il

governo del "doge" Agnello Particiaco si sposta da Malamocco e si insediò nella

zona di Rivo Alto, al centro della laguna. È qui che per convenzione comincia la

"Storia di Venezia".

2. LINEE DI

STORIA VENEZIANA:

LA CONQUISTA DEL LEVANTE

C'è una strana

storia che riguarda il trafugamento del corpo di S. Marco avvenuto in Egitto; la

tradizione vuole che per nascondere alle guardie portuali egiziane il corpo

quando venne trafugato, "scaltri" mercanti lo nascondessero sotto uno strato di

carne di maiale, notoriamente aborrita dai musulmani. Nella prima metà del X

secolo furono due i mercanti veneziani che trafugarono da Alessandria d'Egitto

le spoglie di S. Marco evangelista, e la leggenda narra che lui si fosse

rifugiato su una delle isole realtine, dopo un naufragio. Il corpo viene quindi

"ri-portato" a Rivo Alto e tumulato nell'erigenda cappella del doge, quella che

sarà la Basilica di S. Marco. Aldilà di leggende e trafugamenti avventurosi,

quel che è interessante da un punto di vista storico è la presenza di mercanti

veneziani nel Levante già dal IX secolo!

Ciò significa

che, all'epoca, i "navigatori lagunari" avevano già iniziato ad estendere il

raggio della loro azione. In effetti, a quel tempo Venezia ha già cominciato a

lottare per il controllo dell'Adriatico: deve farlo per sopravvivere, per

difendere i propri interessi mercantili e per... accumulare ricchezze. Come

tutte le potenze marittime, infatti, Venezia alterna azioni di "polizia

marittima", per proteggere i propri scambi e gli interessi di quell'Impero

d'Oriente che ora più che mai lei rappresenta, ad azioni di vera e propria

"pirateria". In questo modo arriva a controllare tutto l'Adriatico. Grazie

all'abilità della sua "marina militare" ottiene decisivi riconoscimenti

dall'Imperatore d'Oriente ed eccezionali privilegi per i suoi mercanti. Alla

fine dell'XI secolo, i veneziani sono i principali clienti e i principali

fornitori di Bisanzio!

Ma l'abilità

della marineria veneziana era integrata da un'altrettanta abile "diplomazia",

che porta il giovane stato ad una serie di fruttuosi accordi commerciali (oltre

a quelli già stipulati con Bisanzio e l'Imperatore germanico) con i principi

nordafricani, siriani ed egiziani. Ormai Venezia vuole diventare il tramite dei

traffici tra l'Oriente e la penisola, perciò inizia una serie di azioni e di

guerre contro i porti rivali dell'Adriatico (Ancona, Zara, Ragusa) e contro i

pirati slavi, passando dal "controllo" al "dominio" del mare. La presa di

Bisanzio fu favorita da un artificio bellico dei Veneziani.

È però con le

Crociate che Venezia ha l'occasione di incrementare la propria posizione sullo

scacchiere del mediterraneo orientale e di risolvere il suo ambiguo rapporto con

Bisanzio. Nel periodo delle prime tre crociate i veneziani avevano avuto

l'occasione di accumulare notevoli ricchezze con le razzie e, soprattutto, col

controllo e coi vantaggi dei commerci in varie aree del Levante. Ma fu con la IV

Crociata che la Repubblica di S. Marco compì il "salto di qualità" e si inserì

nel novero delle potenze marittime. Fu un'impresa guidata dagli stessi

veneziani, che riuscirono a trarne i massimi vantaggi: lungi dal liberare i

luoghi santi e prendendo spunto dalla crisi interna all'Impero d'Oriente, la

spedizione portò, nel 1204, alla conquista e al saccheggio di Bisanzio e allo

smembramento del suo Impero. Alla fine, Venezia conquisterà "un quarto e mezzo

dell'Impero romano", il che si tradurrà nel possesso di tutta una serie di

isole, porti e fortezze costiere nell'Egeo e nello Ionio: l'inizio del suo

Impero Marittimo.

3. LINEE DI

STORIA VENEZIANA:

ASCESA DELLO STATO ("MERCANTILE")

Il successo

riportato con la IV Crociata dava modo a Venezia di consolidare i suoi traffici

con la "Romània" (ciò che era stato l'Impero d'Oriente) e l'"Oltremare", cioè

quelle zone costiere della Siria e della Palestina in cui i crociati avevano

fondato i loro effimeri regni. Porti come Tripoli (del Libano), Tiro, Acri,

Giaffa, Haifa costituivano dei centri commerciali ben appetiti, poiché vi

giungevano delle mercanzie estremamente pregiate e molto richieste in Occidente

come spezie (provenienti dalle Indie), tessuti e prodotti di lusso.

Ma la

concorrenza diventa facilmente rivalità e questa può a sua volta mutarsi in

conflitto. È quello che successe tra Venezia e Genova. La repubblica marinara

genovese si era insediata anche lei nell'Oltremare e, per gli aiuti dati ai

Crociati, aveva ottenuto più privilegi. Ad una serie di incidenti avvenuti in

Tiro, seguirono quattro violente guerre, che nello spazio di circa 120 anni,

sfiancarono e provarono duramente le due contendenti. L'ultimo conflitto fu il

più drammatico per Venezia, perché vide compromessa la sua stessa sopravvivenza:

pressata a nord-est dal re d'Ungheria e dalla Signoria padovana dei Carrara, si

ritrovò coi Genovesi in laguna, dato che nel 1378 conquistarono Chioggia. Ma fu

tutta la città a unirsi strettamente nel momento di maggior pericolo e Venezia

riuscì a resistere e a riconquistare Chioggia. La pace che ne seguì (Torino,

1381) lasciò irrisolti i problemi di fondo che avevano provocato il lungo

conflitto con Genova, ma alla lunga, il solo fatto di essere sopravvissuta e

aver mantenuto le colonie principali la resero la vera vincitrice della lotta.

Il pericolo

corso durante la guerra di Chioggia, convinse i Veneziani della necessità di un

controllo sul retroterra, per impedire che una qualsiasi potenza bloccasse le

vie di accesso alla laguna, vitali sia per la sopravvivenza che per i commerci e

per l'approvvigionamento di materie prime. Iniziò così una fase di espansione in

terraferma. Alleandosi al Signore di Milano, Gian Galeazzo Visconti, Venezia

sterminò i Carraresi di Padova e, agli inizi del '400, conquistò Padova, Vicenza

e Verona. Poco più tardi acquistò anche Bergamo e Brescia, penetrando

profondamente in Lombardia. In questo periodo la potenza navale raggiunge

l'apogeo e la Repubblica di S. Marco assume l'appellativo di "Serenissima" e il

doge quello di "Serenissimo Principe".

4. LINEE DI

STORIA VENEZIANA:

IL DIFFICILE CONFRONTO CON I GRANDI STATI NAZIONALI

L'espansione in

terraferma aveva sancito, per Venezia, il ruolo di "potenza", con tutto ciò che

poteva comportare: i territori, dopo averli conquistati, bisogna anche

difenderli e una politica espansionistica attira sempre le invidie e le

preoccupazioni degli altri Stati.

Così Venezia si

trovò impegnata su due fronti estremamente ambiziosi: il predominio sul mare e

quello sulla penisola italiana. Ma alla fine del '400, grandi avvenimenti

stavano sconvolgendo il mondo: le nuove scoperte geografiche e il nuovo ruolo

degli Stati nazionali. Le prime non fecero sentire immediatamente il loro

influsso sulla vita della Repubblica di S. Marco, ma le seconde sì.

L'invasione

dell'Italia da parte dei francesi nel 1494 apriva un'era nuova per tutti gli

Stati peninsulari e Venezia si trovò impegnata con entità statali molto più

potenti. Il giro di alleanze e la sua strategia la portò nel 1495 a conquistare

avamposti in

Puglia,

area chiave per il controllo di Adriatico e Ionio, e ad ottenere la ricca città

di Cremona. Ma, concentrandosi troppo sulla penisola, perse di vista il suo

impero marittimo e nel 1499 i Turchi la privarono d'importanti città sulle coste

albanesi e greche. Con la pace del 1503 Venezia rinunciò alle sue pretese su

queste città, dimostrando di pensare più ai territori italiani che alla potenza

navale.

Lo spregiudicato

gioco di alleanze e il suo ruolo di prima potenza italiana (come in effetti era

diventata) produssero una colossale alleanza contro di lei: nel 1509 si costituì

la lega di Cambrai che vedeva quasi tutta l'Europa contro Venezia. Dopo aver

tentato di spezzare diplomaticamente la coalizione, Venezia mise in piedi un

esercito colossale per uno stato italiano: 20.000 uomini. Per errori strategici

,esso però fu sonoramente battuto ad Agnadello, in Lombardia, e costretto alla

ritirata. La sconfitta scatenò la ribellione delle città assoggettate, cosicché

Venezia si ritrovò assediata, come nella IV guerra con Genova. Ma ancora una

volta il pericolo suscitò il patriottismo in laguna, mentre nelle provincie

artigiani e contadini si accorgevano dell'arroganza e della ferocia degli

invasori e si aggregavano alle truppe riorganizzate. Dopo sette anni di guerra,

riuscendo anche a rovesciare diplomaticamente molte alleanze, Venezia riuscì a

riguadagnare il grosso dei territori di terraferma perduti.

Dopo questa

esperienza Venezia seguì una politica di neutralità e, con la diplomazia, riuscì

a difendersi dagli invasori che imperversavano nel resto della penisola. Ma il

confronto con le "grandi potenze" vedeva ridimensionata la sua forza sul mare,

data la crescite delle marinerie dell'Impero Turco e di quello Spagnolo.

5. LINEE DI

STORIA VENEZIANA:

ULTIME GLORIE, NONOSTANTE TUTTO

La nuova

situazione che si era venuta a creare con la formazione e il consolidamento di

grandi imperi a est e a ovest del Mediterraneo, metteva Venezia in una posizione

difficile; d'altro canto Venezia si era dissanguata con le guerre italiane e ora

si trovava in difficoltà anche sul mare: le flotte spagnola e turca la

costringevano ad un continuo sforzo di adeguamento.

Intanto nuovi e

pericolosi concorrenti si affacciavano sulla scena mercantile, ma Venezia riuscì

per un certo periodo a tener loro testa, anzi, nel corso del XVI secolo si

verificò una significativa ripresa dei traffici per i mercanti veneziani, che

detenevano ancora buone basi come Cipro, Creta e Corfù fino al 1570.

All'inizio del

1570 il sultano turco sequestra navi veneziane nel Bosforo e nei Dardanelli e

manda un ultimatum alla Serenissima. Il governo di Venezia respinge l'ultimatum

e si mobilita diplomaticamente, ma a luglio una flotta turca sbarca a Cipro e

assedia la capitale.

Venezia cerca di

mobilitare altre potenze e, inaspettatamente, trova un alleato in papa Pio V,

che vede la possibilità di un'ennesima "crociata". Tra mille difficoltà

politiche e diplomatiche si riesce a mettere insieme una coalizione, la "Lega

Santa", i cui principali fautori erano Venezia, gli Asburgo (e certo il Papa).

Il risultato fu

la grande vittoria navale di Lepanto (1571) che, purtroppo, non portò a Venezia

i benefici sperati.

Lepanto, in

pratica, costituì una grande "vittoria morale", celebrata in città in mille

modi, ma non impedì alla potenza navale veneziana di imboccare la via del

declino. Il periodo che seguì vide l'affermarsi di altre vie di traffico (quelle

oceaniche) e il progressivo venir meno delle rotte nel Mediterraneo. Il XVII

secolo si presenta come un periodo di stasi economica e politica. Venezia, sorda

a quanto sta avvenendo negli oceani, cerca di riaprire le vie del commercio

Levantino e di mantenere i suoi ultimi possedimenti. Ma alla metà del '600,

l'Impero Turco la impegna in una lunga lotta per il possesso di Creta, fra

l'indifferenza delle altre potenze impegnate nella "Guerra dei trent'anni". Nel

1669 anche Creta è perduta.

Venezia si

rifarà qualche anno più tardi col suo comandante Francesco Morosini, che diverrà

anche Doge. Egli strapperà ai Turchi il Peloponneso, che la pace di Carlowitz

del 1699 confermerà come ultima conquista veneziana.

6. LINEE DI

STORIA VENEZIANA:

LA FINE

L'ultima

conquista, difficile da mantenere per la lontananza, non ebbe vita lunga: nel

1714 i Turchi si ripresero senza eccessivo sforzo il Peloponneso, approfittando

della solitudine "politica" di Venezia. Tentarono poi di prendere anche Corfù,

ma la resistenza della Serenissima si acuì e stavolta le vennero in aiuto alcuni

stati cristiani, fra cui gli Asburgo d'Austria. Anche grazie al loro aiuto

Venezia riuscì a conservare Corfù (1716), ultimo baluardo di quello "stato da

mar" che tanto inorgogliva la Venezia del passato. Nell'Adriatico ormai le

flotte da guerra straniere operavano tranquillamente senza il permesso di

Venezia, come avveniva in passato. Ormai la potenza navale veneziana è solo

un'ombra: la sua cantieristica è, di fatto, sorpassata e dopo la guerra di Corfù

l'Arsenale si limiterà a produrre meno di una nave all'anno; il ruolo di

"dominatrice dell'Adriatico" è un ricordo lontano e la "temibile" flotta da

guerra veneziana stenta a proteggere i convogli mercantili dagli attacchi

corsari.

Nel contempo la

città gode un'incredibile stagione artistica: i suoi palazzi, le sue chiese i

suoi luoghi pubblici si arricchiscono di un gran numero di opere d'arte, tanto

che il Governo decide di farle inventariare per impedire che finiscano

all'estero; Venezia è, infatti, meta di viaggio di molti forestieri facoltosi e

il suo aspetto e i suoi tesori artistici ne guadagnano l'ammirazione e il

desiderio di conservarne un ricordo tangibile. Ecco, quindi, nasce una scuola

pittorica detta dei "vedutisti", che realizzano celebri "vedute di Venezia"

(ricordiamo, fra tutti i vedutisti, il Guardi e il Canaletto).

All'interno dei

palazzi e degli edifici pubblici furoreggia, invece, l'arte di Giovanni Battista

Tiepolo, autore di bellissimi affreschi. Suo figlio Giandomenico, assieme a

Pietro Longhi, si specializza nella pittura "di genere", rappresentando

deliziose scene di vita sociale e familiare. Nei teatri imperversa la vena

creativa di Carlo Goldoni. Nella sua bottega di scultore Antonio Canova crea il

"Dedalo e Icaro", prototipo di quella scultura neoclassica che lo renderà

celebre in tutto il mondo. E questi sono solo alcuni esempi.

Mentre la vita

del patriziato cittadino si trascina tra feste e attività artistiche, nuovi

grandi avvenimenti stanno sconvolgendo il mondo: le rivoluzioni americana e

francese; l'avvento di Napoleone. Quando il Bonaparte invade la pianura padana,

Venezia rinuncia ad appoggiare Bergamo e Verona che si erano ribellate

all'avanzata napoleonica. Cerca di ricorrere ancora una volta all'abilità

diplomatica, ma l'ambizioso comandante francese passa all'attacco. La classe

dirigente veneziana, imbelle e troppo preoccupata di perdere i possedimenti in

terraferma, accetta le incredibili condizioni e delibera la fine della

Serenissima. È il 12 maggio 1797.

Solo il popolo,

artigiani e bottegai in primis, capisce che dietro le "libertà" strombazzate da

Napoleone c'è la rovina. Si ribella e viene preso a cannonate dal ponte di

Rialto. Ma aveva ragione: dopo qualche giorno Napoleone col suo esercito entra

in Venezia e la saccheggia; ancora qualche mese e la città viene ceduta

all'Austria, diventando, così, suddita dell'Imperatore.

per ulteriori

letture, v.

AA.VV. Storia

di Venezia, voll. I e II (Venezia: Centro internazionale delle grafica e del

costume, 1964).

Lane, F.

C. Storia di Venezia (Torino: Einaudi, 1978).

Zysberg,

A. e Burlet, R. Venezia:la Serenissima e il mare (Milano: Electa/Gallimard,

1995).