Bulat Okudzhava wrote his poem about the Israeli-born female soldier on Eduard Kuznetsov and Larissa Gerstein's kitchen table in Jerusalem. It was in 1996, a year before his death, during one of his visits to Israel. "Your collar is thin/ dark-skinned sabra girl/ you carry a weapon./ But in your eyes is the look of a lady," wrote the Russian poet, as Gerstein feverishly typed the words on a typewriter, simultaneously setting them to music. It can be assumed that it was more the feminine appearance than the military look that touched the soul of the pacifist poet who loved women. When Gerstein played the song on the local Russian-language Reka radio station immediately after the lethal bombing of the Dolphinarium, the studio was inundated with dozens of calls from soldiers' mothers. All of them were crying. What Bulat Okudzhava did for millions of Russians suffering under the yoke of the Soviet regime he continued to do here for a million Russian-speaking immigrants.

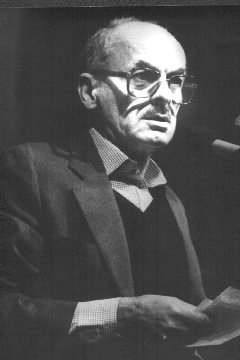

A lone man and his guitar

A festival dedicated to Okudzhava begin this Sunday, on the day that would have been his 80th birthday. The fourth annual festival will include four concerts, to be held in Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, Haifa and Be'er Sheva, with the participation of his widow, Olga, and well-known Russian poet-singers, including his student Veronika Dolina. It would be hard to overstate the importance of the event among the Russian-speaking community here. Okudzhava, like other "bards" over the generations - the Russian troubadours who were characterized by political and social statement, such as Vladimir Vysotsky, Josef Brodsky, Yevgeny Klatchkin and Aleksandr Galich - is a major figure in Russian culture.

|