10-7-2001

FRIDA KAHLO

|

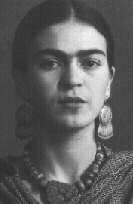

Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo nasceu em 6 de Julho de 1907, em Coyoacan, na

cidade do México. Era o ano da Revolução Mexicana.

Pouco depois do nascimento de Frida, a sua mãe ficou doente e incapaz de a

alimentar ao peito. Frida foi amamentada por uma ama Índia. Anos mais tarde,

ela pintou essa ama como tendo-lhe transmitido uma ligação mítica aos

antepassados mexicanos. Frida descreveu também sentimentos ambivalentes em

relação a sua mãe, que ela considerava amável, activa e inteligente, mas

também calculista, cruel e fanática em religião.

|

|

|

|

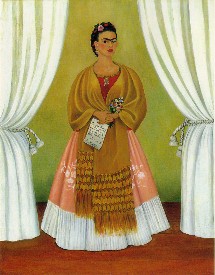

Clique para

ver a pintura

Autoretrato (Dedicado a Leon

Trotsky) 1937

Oil on Masonite 30 x 24

National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington |

|

Por outro lado, Frida, amava

muito o seu pai. Lembrava-se de ter contraído poliomielite aos seis anos e

de seu pai a ter tratado com carinho durante nove meses. Como resultado

desta doença, Frida ficou com uma perna mais magra do que a outra.

Na Escola, Frida era conhecida

como uma maria-rapaz e associou-se a uma banda de rapazes, cuja preocupação

era criar problemas aos colegas e professores. Ainda no secundário, conheceu

o famoso muralista Diego Rivera (1886 - 1957) que mais tarde seria seu

marido e que, na altura, pintava um mural no Auditório da Escola.

A 17 de Setembro de 1925,

quando tinha 18 anos, Frida sofreu um sério acidente de autocarro, quando ia

de casa para a escola, acompanhada pelo namorado Alejandro Gomez Arias. O

autocarro chocou com um comboio, tendo morrido logo vários passageiros.

Frida partiu a espinha em três lados, partiu os ossos do pescoço, várias

costelas, o pélvis e ficou com 11 fracturas na perna direita.

|

|

Em resultado do acidente,

ficou longos meses de cama e sofreu dores toda a vida. Mas, para se

entreter, começou a pintar, de que resultou a sua paixão para a vida.

Ao longo da vida, foi

submetida a cerca de 30 operações. As dores levaram-na a fumar, beber álcool

e ocasionalmente a consumir drogas.

Recuperada, começou a

frequentar a companhia de Diego Rivera e de outros artistas do México, entre

os quais Tina Modotti, a célebre actriz e fotógrafa comunista (1896 – 1942).

Diego e Frida casaram em 21 de

Agosto de 1929. Foi um casamento agitado, entremeado por numerosos affaires

de um e de outro. Divorciaram-se em 1939, mas voltaram a casar um ano

depois.

Apesar dos numerosos affaires

de Diego com outras mulheres, (entre as quais, a própria

Tina Modotti e a irmã mais nova de

Frida, Cristina), ele ajudou Frida a revelar-se como artista. |

|

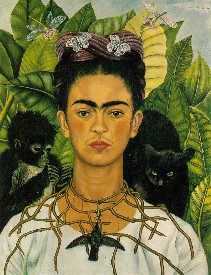

Clique para

ver a pintura

Autoretrato

1940

Oil on canvas

24 1/2 x 18 3/4

Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, Austin |

|

|

|

Presa à cama muitas vezes,

Frida pintava sobretudo auto-retratos. Pintava a sua raiva, os seus

dolorosos abortos, e as dores de que padecia em resultado do acidente.

Apesar disso, Frida era uma

pessoa muito extrovertida. Gostava de beber tequilla e de cantar nas festas

ruidosas que dava em sua casa. Gostava de contar anedotas picantes de chocar

as pessoas. Fascinava os homens e, por isso, teve numerosos affairs, alguns

escandalosos. |

|

Um dos seus amantes foi o

leader comunista, Leon Trotsky. Começou quando este aceitou a hospedagem que

lhe ofereceu Diego Rivera. Frida chegou a ser presa, acusada de cumplicidade

no assassinato de Trotsky, mas foi libertada logo a seguir.

Frida era bissexual e teve

affairs com mulheres.

Frida era admirada por todo o

lado. Quando foi a França, Picasso ofereceu-lhe um almoço e apareceu na capa

da Vogue. |

|

Clique para ver a foto

Tina Modotti |

|

Clique para

ver a pintura

O abraço de amor do Universo,

a Terra (México), Eu e o Senhor Xolotl

1949

Oil on canvas

27 1/2 x 23 7/8

Collection of Jorge Contreras Chacel, Mexico City |

|

Frida fez uma única exposição

na sua vida, na Primavera de 1953. Na altura, já a sua saúde declinava e os

médicos aconselharam-na a não comparecer. Mas ela foi, de ambulância e numa

cama de hospital! A exposição foi um enorme sucesso.

No mesmo ano, amputaram-lhe a

perna direita abaixo do joelho, na sequência de gangrena. Esta operação

deixou-a extremamente deprimida, tendo chegado a tentar suicidar-se.

Faleceu a

13 de Julho de 1954, sendo indicada uma embolia pulmonar como causa da

morte.

|

Week of May

15 - 21, 2002

The Return of the Kahlo Cult

Frida Icon

by

Joy Press

| |

Every

era chooses its own heroes, and Frida Kahlo was the perfect feminist heroine

for the '80s. Hayden Herrera's Frida, the first biography of the then

obscure Mexican artist, was published in 1983, just as Madonna and Cindy

Sherman were parlaying experiments with female self-representation into a

mainstream spectacle. At the same moment, interest in Latin American magic

realism was booming, and Kahlo's audacious, fantastical self-portraits

placed her at the intersection of these otherwise unrelated trends. Kahlo,

who died in 1954, was a crippled, bisexual Communist who painted visceral

images of miscarriage and menstruation and was overshadowed by her more

famous husband, Diego Rivera. Yet in the last 20 years, she's joined the

rarefied ranks of artists like Picasso, whose work is as ubiquitous as

wallpaper. More than just a poster girl for artsy adolescents or a Latina

role model, Kahlo is now a coffee mug, a key chain, and a postage stamp.

Suddenly

a fierce new wave of Fridamania is upon us that is conjuring up a new Kahlo,

customized to suit 21st-century desires. This spring brings the publication

of Kate Braverman's The Incantation of Frida K., a provocative novel

based on her life, and the opening of "Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, and 20th

Century Art," an exhibition at El Museo del Barrio featuring 10 of her

paintings. There's also the inescapable buzz surrounding Frida, the

forthcoming Miramax film starring Salma Hayek and directed by Julie Taymor.

|

|

Defiance

and self-possession: Diego on My Mind (1943)

(image:

Frida Kahlo) |

|

The race to

make a movie of Kahlo's life has been frantic, with Frida admirers like Hayek,

Madonna, and Jennifer Lopez all hatching rival projects. (Both Lopez's version,

to have been produced by Francis Ford Coppola, and Madonna's, which reportedly

would have starred Marlon Brando as Rivera, are out of commission for the

moment.) Miramax's Frida has been postponed until October amid gossip

about wrangles between the director and Miramax boss Harvey Weinstein, but it

was originally slated for release this spring—hence the media blitz that

included a photo spread in Vogue and an odd Times piece on

entertaining: "Kahlo often decorated her table with flowers that spelled out

special greetings. Of course, in Kahlo's case, one might say 'Viva Trotsky,' as

one of her floral arrangements did in 1937 when her favorite Communist visited."

Kahlo's

story lends itself to mass marketing because she consciously forged her own

"brand," painting herself over and over with that trademark unibrow and the

traditional Tehuana costumes she wore to reclaim her indigenous heritage. Her

life was also crammed with movie-ready melodrama and tragedy. There's the

trolley accident that shattered her teenage spine and sent a handrail through

her pelvis, leaving her unable to bear children; the tempestuous marriage to

Rivera, a world-famous artist and compulsive adulterer; her own numerous affairs,

most notoriously with Leon Trotsky. Frida translated this raw material into

paintings that pulse with voluptuous agony and eccentricity.

None of

Kahlo's bloodier work is on display at the current Museo del Barrio show. But if

you stand in the center of the gallery surrounded by all those Fridas, you can't

help but feel singed by her look of defiance and self-possession. Diego on My

Mind (1943) is a beautiful but chilling image of Frida shrouded in a shawl

with a lattice of tiny threads radiating out from her face like roots grasping

for water; embedded in her forehead is a tiny image of Diego. And

Self-Portrait With Bed (1937) has Frida sitting on a bench alongside a

creepy, pot-bellied baby doll—a stand-in for both Diego and the child they could

never have. Although her canvases often reference Rivera, they also exude a

stony solitude. "Loneliness is the key to her subject matter," biographer

Herrera points out. "A feeling of abandonment and separation and

disconnectedness runs all the way through her work."

Frida was

once celebrated as the queen of pain. But now that female misery is

unfashionable (kicked out the door with so-called "victim feminism"), the

current resurrection of Frida Kahlo seems like a reaction against the blandness

of post-feminism. Female icons like Madonna and Courtney Love have ditched

transgression for yoga, replaced by numb nymphets like Spears and Aguilera or

proficient starlets like Witherspoon and Diaz. And so Frida has been called back

into service to incite some rebelliousness.

Julie Taymor,

Frida's director, thinks Kahlo's reputation needs an update. "People

always think of her as the tortured artist, like Saint Sebastian with the arrows

going through him," she says. "I think what turns us all on is the humor and

foul mouth and free sexuality of Frida—that's what makes her interesting to do

as a film."

"Frida begs

to be liberated from the confines of biography," writer Kate Braverman explains.

In The Incantation of Frida K. (Seven Stories Press), a hallucinatory

novel loosely based on the artist's life, Braverman does just that. The author

of several previous experimental novels including Lithium for Medea, she

acknowledges that her Frida is the ultimate unreliable narrator. Doped up on

morphine and nearing death, the artist appears bitter but transcendent.

Several

writers have fictionalized Frida's life over the years—most recently Barbara

Mujica, whose novel Frida (published in paperback this spring by Overlook

Press) is narrated from the perspective of sister Cristina Kahlo, who had her

own affair with Diego Rivera. Mujica plays the facts pretty straight, whereas

Braverman's harrowing book takes such imaginative liberties that it's likely to

piss off some of Diego and Frida's faithful fans. Incantation embellishes

Frida's story with kleptomania, opium-den hopping, seedy sex with sailors, and

lots of lesbian love affairs. After numerous miscarriages, she resolves her

sorrow by carrying an imaginary daughter around in a ring box: "I let her crawl

around the grooves in my palms, slide along my life and health lines. I put her

in an ashtray so she could watch me work."

Braverman

says she chose Kahlo as a protagonist because "she was a painter, a morphine

addict, the first woman psychoanalyzed in Mexico—she's a prototype of female

modernity. The trick was to invent a voice for the inner Frida, and to find a

literary style as poetic and dangerous and prophetic as the paintings are. I

felt I was an anthropologist discovering the subterranean Frida."

The most

controversial element of The Incantation of Frida K. may be its portrayal

of Diego Rivera as an almost monstrous figure with "the heart of a

butcher." But Braverman insists that her Frida and Diego are not at war—they

are entangled in a symbiotic relationship. "He cajoles her and he keeps her

alive," she says. "At one point in the book he tells her, 'I give your agony

focus.' "

Like Sylvia

Plath, that other goddess of the angsty teen-girl set, Frida is sometimes

lamented as a female genius overshadowed by her repressive, adulterous husband.

But Taymor sees her movie as a love story, and has no sympathy for Diego

detractors. "If people criticize the movie by saying our Diego is too nice—I

would fight with that, because if you admire Frida, you could never present her

as a woman who would just be abused. He was a giant, ugly man, so obviously

there had to be a lot in Diego for her to want to be with him all those years,"

she says heatedly.

"Frida took

on a marriage knowing that this man's capability for fidelity was pretty slim,"

Taymor continues. "But the way she resolved her frustration was phenomenal. This

woman didn't sit in the corner and mope; she took on her own sex life. What I

find so fabulous and disturbing is that they never stopped loving each other

through all that. . . . At the end when she was at her worst, her health was

failing and she was alcoholic and addicted to drugs because of the pain—he came

back to her."

Taymor,

known for her avant-garde puppetry and for directing the stage version of The

Lion King and the movie Titus, seems like the perfect filmmaker to

bring Frida to the screen. The two artists share a visual sensibility

that combines fantastical and folkloric imagery with tactile realism. "I was

very attracted to the notion of how to realize her paintings in a surreal way,"

Taymor says. She brought in lyrical-goth animators the Brothers Quay to reenact

Frida's post-accident hallucinations—a scene that some believe is at the heart

of a dispute between Taymor and Miramax honcho Harvey Weinstein.

"The movie

will be amazing if Harvey Weinstein keeps his hands off of it," says Herrera,

whose biography was the basis of the screenplay. "If you're hiring a genius like

Taymor, you can't then say, I want to cut these 10 seconds or whatever it is.

And she's as fierce as he is. She is the most focused person I've ever worked

with." Currently in Brazil recording the film's soundtrack, Taymor won't comment

on the rumors except to say, "We got tremendous scores in the previews. And we

found males and females like the movie almost equally—can you believe it?

Because it's not just her art, it's about her life."

Everyone has

their own take on Kahlo's magnetic appeal. Braverman says that her Frida "is a

thrill seeker, a delinquent, a revolutionary. . . . She spent so much of her

life in solitary confinement in hospitals that I think Frida lived posthumously.

In my book she is fueled by the myth she's creating."

According to

Taymor, "She made herself an icon. She took her imperfections and made them the

ultimate. She made her eyebrows and her mustache much more prominent than they

were in real life; she emphasized what we would consider the ugly parts and made

them beautiful. I think that appeals to many people because it tells them you

can make something extraordinary out of ugliness."

Once the

film hits the screen this fall, moviegoers will likely begin nursing their own

personal Frida fantasies. "Frida Kahlo would have loved all this attention,"

Herrera says with a chuckle, "because she painted self-portraits partly to get

people to acknowledge her." And she probably would have been thrilled to see

petite Mexican starlet Salma Hayek decked out in frilly skirts and chunky

jewelry, her face garnished with unibrow and mustache. Says Herrera, "There's

one scene in my book where she's walking down the street with one of her doctors

and they pass a pretty woman. Frida says, 'I'll smoke that one myself.' That's

probably what she would have said about Salma."

Fiction

Paint and Suffering

Reviewed by David Huddle

Sunday, June 9, 2002; Page BW08

THE INCANTATION OF FRIDA K.

By Kate Braverman

Seven Stories. 235 pp. $23.95

The virtuoso prose

performance Kate Braverman puts on in The Incantation of Frida K.

produces a dazzling and illuminating novel that is also irksome and monotonous.

Author of nine previous books of poetry and fiction, notably Lithium for

Medea and Palm Latitudes, Braverman has a talent for lyrical and

hallucinatory language that neatly matches her subject, the interior musings of

Frida Kahlo on her deathbed at age 46.

Kahlo's extraordinary life,

documented in her paintings and The Diary of Frida Kahlo, published in

1955, was characterized by triumph over disaster. The woman who has become

Mexico's best-known artist suffered from polio as a child; as an 18-year-old

student she was severely injured in a bus accident in Mexico City; she endured

nearly 30 surgeries in the midst of a chaotic marriage to Diego Rivera, "the

master mural painter"; and she longed for children but could not tolerate

pregnancy. In Braverman's novel, Kahlo verbally sketches her life over and over

again: "First I lost my body. My children. Then I lost my husband, though he was

never quite mine."

Like Sylvia Plath, Frida

Kahlo has become a feminist icon, in part because of the sexual politics of her

marriage to an older, established artist in her own field. Rivera and Kahlo were

famously unfaithful to each other, and The Incantation of Frida K.

demonstrates how perversely and equally they were matched. Some of Braverman's

most vivid passages are Kahlo's deathbed view of her husband: "The big man,

enormous in his flesh, two hundred and sixty pounds of him, meat and wine and

chocolates, and other women's mouths with their burgundy and vermilion lipsticks,

with their jasmine and musk, their martinis and mink trim. Diego, scuttling away

from a tiny woman who is inexorably turning into water."

The Incantation of Frida

K. offers occasional gems of insight into art history: "After the war, it

was obvious that it was I, Frida, who painted recognizable events. Diego was the

surrealist, with his slow sun-bloated women, bovine with their corn stalks,

their ridiculous lilies, and their enormous static harvests. Diego did not

include radium in his palette. He did not acknowledge poisons in the rivers,

flowing into vines, in breasts that give tainted milk." Braverman's primary

accomplishment, however, is that in general she conveys Kahlo's indomitable

spirit, and in particular she illuminates an artistic consciousness deeply

informed by physical suffering.

Frida recalls the aftermath

of the bus accident: "Doctors deposited me outside, on the boulevard, on

cobblestones, with those too mutilated to survive. I had fractures of my spine,

of my third and fourth lumbar vertebrae. I had pelvic fractures and a fracture

of my right foot. . . . My right leg was broken in sixteen separate places. . .

. That is what opened for me when my body was crushed. The ocean blew in. I

became a harbor."

In a way that no biography

could ever be, The Incantation of Frida K. is true to Kahlo. To read this

book is not only to understand what made the artist tick, it is also to feel the

excruciating ticking of a life fueled by pain. Braverman's powerful empathy with

Kahlo and commitment to Kahlo's voice are both the achievement and the undoing

of the novel. Even by artistic standards, Kahlo was self-obsessed -- of the

roughly 200 paintings she completed, about a third are self-portraits. She was,

as a caption for one of those portraits puts it in a recent show at the

Metropolitan Museum in New York, "her own favorite subject."

And though the details of her

life conjure up a compelling story, Frida's view of herself, as The Diary of

Frida Kahlo makes abundantly clear, was imagistic and nonlinear. Kahlo's

telling of her own life takes most of the narrative out of it; Braverman's novel

transforms a great story into a surrealistic prose poem spoken in the voice of a

narcissist. Never mind that the speaker is an artistic genius whose life was one

of the most fascinating of the 20th century; never mind that she managed to

transform incredible pain into striking paintings; never mind that she's on her

deathbed and deserves to be heard; and never mind that the language she uses is

intense, fresh and often pretty funny: "I drink to drown my sorrows . . . . But

the damn things have learned to swim." It's still exhausting to listen to

someone talk so relentlessly about herself -- or to read 235 pages of such

talking. •

David Huddle is the author

"La Tour Dreams of the Wolf Girl."

September

19, 2003

ART REVIEW | 'FRIDA KAHLO'

The Multicultural Identity

Beneath Frida Kahlo's Exoticism

By GRACE GLUECK

You would

think that there was not much left to explore about Frida Kahlo (1907-1954), the

Mexican painter who is one of the starriest idols in the feminist pantheon. But

a determined art historian can always dig up more. The message of "Frida Kahlo's

Intimate Family Picture," a small painting-cum-photography show at the Jewish

Museum, seems to be that Frida was half Jewish.

That fact

was not unknown, but it has been somewhat buried in the flood of material

already unearthed about Kahlo's life. Now, a guest curator, Gannit Ankori of the

Hebrew University in Jerusalem, has organized a show based partly on her

doctoral dissertation, which dwells on the issue of Kahlo's "hybrid and

multicultural identity."

What we

learn is that Kahlo's beloved father, Guillermo (Wilhelm) Kahlo (1872-1941), was

the son of a Hungarian Jewish couple who emigrated to Germany. Arriving in

Mexico at the age of 18, he became a professional photographer whose main

subject was Mexico's colonial architecture. Frida was the daughter of his second

wife, Matilde Calderón, a "mestiza" or a woman of mixed race, in this case

Mexican and Spanish, who brought up Frida and her siblings in the Roman Catholic

faith.

Her early

religious roots didn't concern Frida much (as an adult, she became an ardent

Communist), but in 1936, probably affected by the growing menace of Hitler's

anti-Semitism, she painted "My Grandparents, My Parents and I," a family

portrait that included her Jewish ancestors. The painting, owned by the Museum

of Modern Art, is the centerpiece of the show. It is accompanied by a smattering

of related material, in the form of photographs, books and reproductions of

other paintings.

"My

Grandparents" shows Frida as a small child, standing naked in the courtyard of

the Casa Azul, the comfortable home built by her father in Coyoacán, then a

village south of Mexico City, where Frida spent most of her life. (She died

there, and it is now the Frida Kahlo Museum.) In her right hand she holds a

ribbon that flows upward on either side of the picture to support floating

portraits of each set of grandparents; the Mexican couple on the left, the

Hungarian-Jewish pair on the right. (From her Kahlo grandmother, Frida

apparently inherited those awesome black eyebrows that almost met in the middle

of her forehead.)

Directly

behind Frida are portraits of her mother and father, taken from their wedding

pictures. Her mother wears a long-sleeved white gown, ruffled at the neck;

superimposed on it below her waist lies Frida as a fetus, umbilical cord snaking

up to where her mother's navel would be. Her mother's arm rests on the shoulders

of her father, a mustached personage shown as a portrait bust duded up in a

wedding suit. Just below the edge of her mother's dress is an ovum about to be

inseminated.

Other

material in the show includes reproductions of paintings, among them Henri

Rousseau's "Present and the Past" (1898), a depiction of the painter and his

wife that apparently inspired Frida's rendering of her own family. Several books

are in evidence from Frida's library; one is a study of the torture of Jews by

the 16th-century Inquisition in Mexico; another is an illustrated tome on the

practice of obstetrics.

A Nazi

chart explaining who was considered Jewish, included in the exhibition, would

seem to be another documentary source for Kahlo's family painting, reflecting

her recognition of her "impure" roots. And a painting, "Without Hope" (1945), by

Kahlo herself, depicts her in a four-poster bed, tears flowing, with various

elements fantasizing her own persecution by the Inquisition.

A strong

part of the show is a vivid group of photographs of Kahlo at various stages of

her life, most taken by her father. At 4 she is a chubby little girl in a white

dress, holding a bouquet of roses; at 18, handsome and serious, she gazes at the

viewer with a self-confidence unusual for her age. At 25, several years after

her marriage to the philandering painter Diego Rivera, she is seen in native

costume, presenting herself as an exotic whose roots were in the indigenous

culture.

So, is

Kahlo's Jewish identity — not otherwise very evident, to be sure — a compelling

basis for a show? Not to my thinking. But the show, like any other Kahlo

exhibition, does raise the issue of just how good a painter she was. Or how much

of the adulation given her stems from her personification of the suffering

female, bravely bearing up under the trauma of severe physical affliction —

childhood polio and permanent injuries from a youthful accident — her difficult

marriage and her troubles in finding acceptance as a woman and an artist.

Still,

there is no denying that the personal thrust of her paintings gives them power.

She obsessively chronicled her life, hard times, physical distress and dreams,

in a lively, primitive style that spares nothing in the way of morbid clinical

detail. And if her work often gives the impression that she was a better medical

illustrator (a profession she aspired to early in life) than a truly

accomplished artist, who's to complain? Through her creepy paintings, you

feel her pain.

Jan. 4, 2004

The tortured genius of Frida Kahlo

By

MEIR RONNEN

Frida Kahlo: the Painter and her Work

by Helga Prignitz-Poda.

Schirmer/Mosel

261 pp. €78

Available in English, German and French editions.

Back in the days when I thought I was the only one here who had ever heard of

her, I called her Miss Eyebrows of 1932.

More than anything else, the eyebrows of Mexican painter Frida Kahlo (1907-54)

are the best-remembered detail of her many astonishing self-portraits.

Kahlo, wife of painter Diego Rivera and lover of several notable men, including

Leon Trotsky, has recently become a household name, partly because of a colorful

movie about her amazingly colorful life and partly because of a series of

exhibitions about her and her work, the latest at the Jewish Museum of New York.

There is even a Frida cult site on the Web.

And now Schirmer/Mosel of Munich has published a huge book, Frida Kahlo, the

Painter and her Work, by Helga Prignitz-Poda. It is the last word in Kahlo

studies, and contains texts for each of the many color plates.

Kahlo was not only a compulsive self-portraitist but a symbolist/surrealist, at

times affected by her fierce left-wing outlook and at others by her

considerations of feminism and Buddhism. She painted and loved in a world of

pain, the result of a road accident in 1925 that crushed her pelvis and lower

spine.

Kahlo's multi-cultural identity was there from the outset. Her father, Wilhelm

Guillermo Kahlo, was a German-Jewish photographer and sometime painter, scion of

a family of Hungarian Jews who had settled in Baden-Baden; he encouraged every

aspect of her intellectual development. They appear to have been close, and her

late portrait of him in this book is stylized but essentially sympathetic. Her

mother, Matilde Calderon, was a Mexican Catholic mestiza of Spanish and Indian

descent, more formal and distant than her husband.

Frida was born in Coyoacan, near Mexico City, and survived childhood polio,

nursed mainly by her father. Her family home, the Casa Azul, appears in her

painting My Grandparents, My parents and I. Frida lived there for most of her

life. Her ashes are kept there, and in 1959 the house and its collection became

the Frida Kahlo Museum. More recently, Mexico has officially recognized her as

"a national monument."

Frida taught herself to paint while recovering from her accident in 1925. A few

years later she showed her work to Rivera, and made up her mind to marry him.

They married in 1929, later divorced, and then, in 1940, remarried. More often

than not, as can be seen from a number of self-portraits, she painted from a

wheelchair; before she died, despairing of her health, a leg was amputated.

Kahlo's first major self portrait in this book is from 1932, and shows her in a

pink dress standing on the border between Mexico and the US; part of it depicts

Detroit, but the work places her between the New and Old Worlds - a border she

straddled all her life. Her diary reveals, among other things, her admiration

and love of Breughel.

More startling works follow: an extraordinary depiction of her birth made the

same year, in which her mother's head is hidden under a sheet as her own

emerges; and a bloody sex murder, her reaction to Rivera's brief affair with

Frida's sister Christina. Even the plain wooden frame of this work is spattered

with "blood."

From 1937 is a formal self-portrait she gave as a present to Trotsky after the

end of their affair, rendered with her usual mastery of the rhythm of drapery;

in it she holds a letter of dedicatory thanks dated November 1937.

IT WAS a traumatic year, in which she also painted My Nurse and I, an oil on

sheetmetal showing her in the arms of a female idol. A symbolic bouquet issues

from Frida's mouth; her woman's head is tacked onto a child's body. Another oil

on metal from the same year, Memories of My Heart, is almost Dali-esque in it

surrealism; a hole in her chest where her heart should be, she stands next to a

huge bleeding heart on a shore; at each side is a dress from childhood and

adulthood; one foot is on land, the other on the sea. This work expresses all

her dichotomies.

In 1938 she painted Fruits of the Earth, a superb tabletop still-life of fruits

and vegetables, with clouds behind the table. It contains several pears, and for

author Prignitz-Poda the mushroom stalk is distinctly phallic. Whatever the

case, its placement is part of an astonishingly efficient composition.

By 1938 animals began to appear in her self-portraits: first a dog and then

monkeys, the latter a guardian and sex symbol with rather human expressions that

reflect her own. The monkey appears again in The Earth Itself, 1939, an oil on

metal which depicts another recurring theme - that of young two nudes, one

white, the other brown, the latter her imaginary friend, backed with a carefully

organized tangle of vegetation. In it sits the monkey, a tiny but ever-present

reminder of sex - and perhaps of Rivera, who first brought her one.

Despite Frida's preoccupation with herself as prime subject matter, she

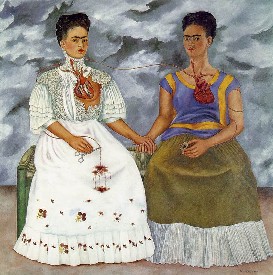

continued to astonish. The famous Two Fridas from 1939 with linked hearts is

another accomplished composition, a reminder that she was primarily a wonderful

image maker, whatever the animus.

Later works reproduced here show her as a martyred hind, filled with more arrows

than Saint Sebastian, or with Rivera painted in her brow, her third eye. Many of

her portraits are splattered with either blood or tears. Another represents her

dying, bereft of hope as her innards emerge from her mouth.

Her last two portraits reproduced in this book are of her father and her doctor.

Her written dedication to her father is more than words from a loving daughter,

but a tribute to his resilience in dealing with 60 years of epilepsy, and his

staunch resistance to Hitler.

Frida Kahlo was not just a driven, tortured woman with a lust for life. Her

horrific images are not what made her a great painter, but rather her ability to

organize them into remarkable, if not great paintings.