10-6-2005

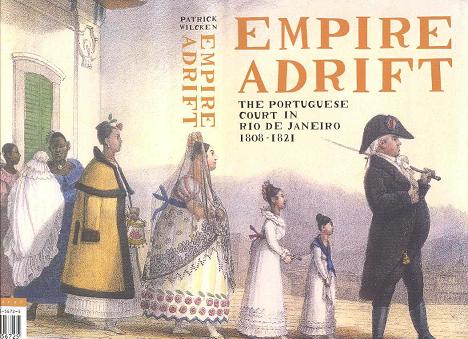

Empire Adrift: The Portuguese Court in Rio de

Janeiro

by Patrick Wilcken

PORTUGAL:

O Império à Deriva, Civilização Editora, Porto,

2005, ISBN: 9722622528, 328 págs.

BRASIL:

Império à Deriva, a Corte Portuguesa no Rio de

Janeiro,

Objetiva, Rio de Janeiro, 2005, 326 págs.

ISBN: 857302738X

A tropical Versailles

In

1807 the entire, ill-assorted Portuguese court fled to Rio and stayed for 13

years. John Ryle applauds Patrick Wilcken's Empire Adrift, a brilliant account

of a bizarre yet momentous event

Saturday October 23, 2004

The Guardian

Empire Adrift

by Patrick Wilcken

320pp, Bloomsbury, £16.99

|

In his novel The Stone Raft (1986), the Portuguese Nobel laureate José

Saramago imagines the entire Iberian peninsula breaking away from Europe and

drifting across the Atlantic towards the tropics. Saramago's allegory of

detachment reflects Portugal's role as the earliest of Europe's seaborne

empires and nostalgia for the wonder years of the 16th century, when this

tiny ear of land (as an earlier Portuguese writer referred to it)

established a colonial presence in India, China, Africa and the Americas, a

time that saw the beginning of Europe's long and violent romance with the

peoples of the south. |

|

|

|

Patrick Wilcken's Empire Adrift takes as its subject another remarkable episode

in Portuguese imperial history: a time of dislocation in the early 19th century,

when the royal family, the Braganças, confronting the prospect of invasion by

the French, fled to South America by sea, remaining there for more than a

decade. It is a story that also resonates with Saramago's dream of a vagrant

Iberia, drifting south.

The flight of the Braganças took place at a critical moment in western European

history, when the Peninsular war was hotting up. Eclipsed by Britain and France,

Portugal was in decline. Napoleon's army was advancing from the north. The

deposed kings of France and Holland had both gone into exile in England; the

British fleet was blockading the Tagus in an attempt to counter the French

advance. As the French army drew closer to Lisbon, the Portuguese prince regent,

Dom João, under pressure from the British envoy, took a decision that would be

fateful not just for the Portuguese crown, but also for Brazil, the new world

colony that was the mother-country's major source of revenue.

On November 29 1807, a day before the French army entered the city, Dom João and

his Spanish Borbón queen, Dona Carlota, fled by the only route available to

them: the sea. The scene rivalled the fall of Saigon. A convoy of three dozen

frigates, brigantines, sloops, corvettes and ships-of-the-line, with the entire

Portuguese court on board, 10,000-strong, set sail for Brazil with a British

escort vessel, braving the winter storms of the Atlantic. Religious dignitaries,

government ministers, military officers, their families and servants - and Dom

João's mad mother, Queen Maria - made up the complement of passengers on the

three dozen vessels. The ships also carried the imperial regalia, the royal

carriage, a piano and several tons of books and documents, the paperwork of

empire.

Two months later, lice-ridden and in rags, the Portuguese court arrived in

Brazil. After a brief sojourn in Salvador, the old capital, they proceeded to

Rio de Janeiro, then a noisome slave port with narrow streets filled with

rootling pigs and goats. And in Rio, to the bemusement of the colonial

population, the royal party proceeded to re-establish the European imperial

court in all its archaic magnificence, with the ritual trappings and hierarchies

of an absolutist state. On the shores of the Guanabara Bay, against a backdrop

of sheer rock for which the city is celebrated, the Portuguese created what a

Brazilian historian called a tropical Versailles or, to use Wilcken's phrase, a

sub-tropical Rome.

Wilcken tells this unfamiliar yet extraordinary story with élan. Empire Adrift

is a model of historical writing, erudite yet lively, maintaining narrative

vigour while accurately rendering complex events at different times in different

continents. Wilcken combines a sense of place with a keen eye for the grotesque.

He has a striking cast of characters to work with. There is the dowager Queen

Maria, half-demented and permanently in mourning for her husband; the egregious

Lord Strangford, British envoy to Lisbon and Rio, a spin-doctor avant la lettre

, always eager to steal the credit for any diplomatic advantage gained. There is

Dom João himself, short, fat and indecisive, excessively fond of food but also

keen on conversation with men of learning. And Dona Carlota, his scheming wife,

a child bride who tried to bite her husband's ear off on their wedding night and

contrived, for the rest of her life, to spend as little time as possible in his

company. (As dysfunctional families go, the Braganças and their in-laws, the

Borbóns, make our Windsors and Bowes-Lyons look tame.)

Finally there is Dom Pedro, their son (probably - his paternity was disputed),

who grew up in Brazil an unrestrained philanderer, handsome, half-educated,

urinating and defecating without embarrassment in front of his troops, and

referring to his mother ungallantly as a "bitch", but who became, in the end,

the standard-bearer of Brazilian independence.

The Portuguese court remained in Rio for 13 years. Dona Carlota hated every

moment. She saw Brazil as the domain of "blacks and monkeys", and longed to

return to Europe. But Dom João, though terrified by the thunderstorms that swept

across the Guanabara Bay, quickly took to life in the new world, overseeing the

rebuilding of the capital and the establishment of Rio's botanical garden, the

latter, in Wilcken's phrase, a laboratory of empire that rivalled Kew. When the

time came to return to Portugal, with Napoleon defeated and the British

impatient to restore royal authority in Europe, Dom João - now King João VI of

the United Kingdoms of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarve - found himself

reluctant to leave.

In the end he did return, but Dom Pedro stayed on in Brazil as his regent. Aged

nine at the time of the flight from Lisbon, Pedro had spent most of his life in

Brazil. And in 1822, with Dom João in Portugal beset by demands for

constitutional reform, and anti-colonial, republican movements gathering force

in the rest of Latin America, the young regent made a unilateral declaration of

independence from Portugal. Thus, as Emperor Pedro I of Brazil, he established

the first European monarchy of the new world.

It was an act that appeared to go against the tide of history, both in Europe

and the Americas. As if George III and the entire British ruling class had

abandoned Great Britain for North America to escape the Napoleonic wars, and

George IV, rather than George Washington, had led the United States to

independence. Or as if Queen Victoria had moved the seat of government to India.

But it was Dom Pedro's action, arguably, that made it possible for Brazil to

remain a single country. Despite its huge size, Brazil survives today as a

stable, independent state while the multifarious republics of Latin America and

Central America reveal, by contrast, the fragmentation of the former Spanish

empire. The Brazilian monarchy was finally abolished only in 1889, and Braganças

still crop up in the social register. There is even a Brazilian royalist party -

and more than one claimant to the throne.

The British did well out of the relocation of the Portuguese court. They forced

Dom João to open Brazilian ports (previously confined to Portuguese shipping) to

"friendly nations", principally Britain. Rio was immediately flooded with

British manufactured goods that had been excluded from European markets by the

Napoleonic blockade. English glassware and textiles and Irish butter were on

sale. The first pub opened. A British fabric trader, Wilcken reports, found that

the textiles he was importing were not bright enough. The people of Rio, he told

his suppliers, wanted "no dismal colours suitable for an English November".

Brazil still bears the marks of this British invasion, with a telling pair of

expressions in general use: pontualidade britânica (to be on the dot), and para

inglês ver (to put up a front, to cultivate appearances).

One group that did not benefit from the royal sojourn were slaves. Slaves

comprised a third of the inhabitants of colonial Brazil, and tens of thousands

more arrived from Africa each year. They were a critical factor in the economy.

Like Rome, as Wilcken points out, the new imperial capital was built by slave

labour. But the privations the members of the Portuguese court had endured on

their voyage across the Atlantic did not, it seems, make them more sympathetic

to the sufferings of slaves, who had endured a hundred times worse in their

involuntary passage. British pressure may have opened the ports of Brazil to

free trade in goods, but it seemed it could not close them to the slave trade.

It was only in 1888 that the Princess-Regent, Dona Isabel, Pedro I's

grand-daughter, finally abolished slavery, an act that contributed, ironically,

to the abolition of the monarchy the following year. In Brazil, in this respect,

in the final years of their tenure, the royal family became a progressive force.

So Brazil changed the Braganças; and the Braganças changed Brazil. The story can

be seen as a case of what the Brazilian sociologist and historian Gilberto

Freyre called lusotropicalism, a special affinity for the tropics that the

Portuguese, according to Freyre, entertained to a greater extent than other

Europeans. Or it may be seen as an agile political response to the end of

absolutism. Saramago's stone raft, Freyrian lusotropicalism, or the material

opportunities and hard constraints of history - however these events are

interpreted, it was in Brazil that the extraordinary story of the Portuguese

seaborne empire - first into the southern hemisphere, and last to leave -

reached its most curious and spectacular conclusion.

John Ryle is chair of the Rift Valley Institute.

The TLS n.º 5311, Friday 14 January 2005

Scratcher and the

cheese man

Peter Burke

Patrick Wilcken

Empire Adrift

The Portuguese Court of Rio de Janeiro,

1808 – 1821

300 pp. Bloomsbury, £ 20

0 7475 5672 5

In some important ways, the history of

Brazil has been very different from that of all the other countries in Latin

America. The Spanish Americans won their independence from the mother country by

insurrection and war, but in Brazil the transition from colony to independent

state was a peaceful one. Surprisingly enough, the ultimate responsibility

for this rests with Napoleon. In 1807, faced with a French invasion, King

João VI and his ministers decided that the best thing to do was to take refuge

in the New World, in Rio de Janeiro. It was there, in 1815, that the King

declared Brazil to be a kingdom, on equal footing with Portugal itself. When

Dom João returned to Portugal in 1821, he left his son Dom Pedro behind as

Prince Regent, and the next year Pedro declared Brazil to be separated from

Portugal. The transfer of the Court also ended Brazil’s cultural isolation.

Printing presses had been prohibited until this time, but from 1808 there was a

regular newspaper.

The Portuguese Court’ s thirteen years

in the tropics, 1808—21, were a crucial period in Brazilian history, which,

understandably, has attracted a number of scholars. The distinguished diplomat

and intellectual Manuel de Oliveira Lima wrote a book about it that appeared in

1908, just in time for the centenary of Dom João’s arrival. Leading

Brazilianists such as Alan Manchester, Leslie Bethell and Kenneth Maxwell have

published essays on the transfer of the court and its consequences. An American

historian, Kirsten Schultz, published a book in 2001 under the engaging title —

taken from Oliveira Lima — Tropical Versailles (reviewed in the TLS,

September 6, 2002) analysing the significance for both Portuguese and

Brazilian history of the sojourn of the court in Rio. Patrick Wilcken is also

interested in the geopolitical consequences of the transfer of the court, but

his principal aim, in Empire Adrift, is to tell a good story. He writes

well, describing events or evoking characters. The narrative is fast-moving and

lucid, making pauses or digressions to place events in context, to explain how

the Portuguese Empire came into existence, for example, or why it was that

Brazil exerted such a strong attraction on scientists in the early nineteenth

century thanks to its exotic fauna and flora. Wilcken is concerned with what he

calls “descriptive immediacy” and he certainly achieves his aim, using his

imagination where documents are lacking in order to make his readers not only

see but also smell and feel the discomforts of the long voyage from Lisbon to

Rio: “Accommodations would have been primitive, privacy nonexistent, sleep

difficult if not impossible on the open deck, with sea spray regularly showering

over the rows of nobles stretched out on the timbers”. Again, the landing of the

Portuguese in Brazil is vividly described, marking the contrast between the

overdressed Europeans and “their colonial cousins” who wore clothes better

adapted to the climate, and the surprise of the visitors when they saw

“Afro-Brazilian women wearing jewellery and African men sporting top hats,

walking canes and snuff boxes”.

Rio is a constant and vivid presence in

this book, viewed not as a “tropical Versailles” so much as a “sub-tropical

Rome”, a mixture of period from 50,000 to 100,000 people, making it one of the

leading cities of the Americas. Wilcken also has a gift for evoking

personalities, notably those of Dom João and his Queen, Dona Carlota, both of

them larger than life. The King is described as “a short stout man, with a large

head and stocky arms and legs”, who suffered from skin diseases, scratched

himself in public, and liked old clothes, eating chickens, church music and

botany. his best memorials are surely the Botanical Gardens in Rio, which he

founded, and the incredibly tail imperial palms, named in his honour. As for

Dona Carlota Joaquina, Dom João’s Spanish wife, she kept a separate household

and conducted a “conjugal guerrilla war” with the King. Her love affairs were

notorious, in Brazil as in Portugal. Played unforgettably by Marieta Severo in

Carla Camurati’s film Carlota Joaquina (1994), the Brazilian equivalent

of The Madness of King George, Dona Carlota was short, lame, angular,

frizzy haired, hot-tempered and uninhibited, an “irrepressible personality and a

prima donna who needed to be the centre of attention and dressed in an

eccentric, flamboyant style. The French artist Jean-Baptiste Debret depicted her

with feathers on her head, “a kind of early nineteenth-century Carmen Miranda”.

A couple like this — not to mention Dom João’s mother, who had gone mad — lend

themselves to grotesque treatment, but Wilcken treats them with sympathy.

The main reason that this episode in

Portuguese and Brazilian history has attracted Anglophone scholars is because of

Britain’s role in the affair. When Napoleon put pressure on Portugal to join the

blockade of Britain, the British advised Dom João to take refuge in Brazil,

offering to provide a naval escort for the ships taking the Court to the New

World. The offer was a difficult one to refuse because it was clear that the

British were prepared to bombard Lisbon (as they had recently bombarded

Copenhagen) in the event of a refusal, and to destroy the Portuguese fleet in

order to prevent it from falling into French hands. The price of protection was

the opening of Brazil to British exports, denied their usual outlets by

Napoleon’s blockade. It was not only the Portuguese Court that arrived in Rio in

1808, but also various English merchants, “buying up all available space in the

city’s warehouses, renting shops in the centre and snapping up the most sought

after properties on the surrounding hill-sides”. In the 1940s, the Brazilian

historian Gilberto Freyre described this episode in a brilliant essay in his

Ingleses no Brasil (a book that has sadly never been translated into

English). Rio was invaded by British products such as beer, cheese, Chippendale

furniture, Sheffield cutlery and porcelain tea services. A royal edict of 1808

banned traditional wooden shutters, describing them as “barbaric”, “Gothic” and

“Turkish”, and ordering their replacement by glass windows, made in England. It

is true that some items did not sell, and that it was necessary for the

Yorkshire merchant John Luccock to write home to explain that heavy overcoats

were unnecessary in a tropical climate and that drab colours were inappropriate

for sunny Rio. But, despite such mistakes, the impact of the British on

Brazilian culture was extremely important in the long term.

While the French influence was

exercised by means of a so-called Artistic Mission of architects and painters

who arrived in 1816, as well as through the dressmakers, hairdressers and

milliners who reached Rio at about the same time, that of the British was felt

primarily through trade. Wilcken largely concentrates on the political

situation, in which the British envoy Viscount Strangford played an important

part - as was common for diplomats in an age before the telegram and the

telephone. Besides the many printed sources, the author has studied Strangford’s

correspondence with London in the archives of the British Foreign Office.

It is fascinating to learn that George

Canning, who was Foreign Secretary at the time, was hoping that British

merchants would “make the Brazils an Emporium for the British Manufactures

destined for the consumption of the whole of South America”.

Where culture is concerned, the

author’s touch is less sure, and a few errors have crept in, from the use of the

term “Romanesque” to describe nineteenth-century architecture, to mistaking the

gender of the figure representing America at a festival in 1810, claiming that

King Sebastian of Portugal was “beheaded” (after the defeat of Alcazarkebir —

Ksar ei Kebir, in Morocco — the King’s body was never found). Wilcken does not

have anything very new to say about the political consequences for Brazil of the

transfer of the Court, but this would have been a difficult task so soon alter

Kenneth Maxwell’s brilliant essay on the subject. Maxwell views this episode as

crucial for Brazil’s escape from the divisions, conflicts and civil wars that

followed independence in Spanish America. (He discussed the potential

consequences of Carlos IV of Spain’s asylum in -Mexico — an option he seriously

considered— which is a fascinating example of what Niall Ferguson calls “virtual

history”.) What Wilcken offers are some interesting reflections on the long-term

consequences for Portugal of the thirteen-year absence of the King. In general,

he succeeds at a hard task: writing both for specialists and for general

readers. By telling a good story, and placing it in multiple contexts, lie makes

Empire Adrift a distinguished and enjoyable first book.

Question:

Why did the entire Portuguese royal family move to Brazil?

The immediate reason for the Portuguese court's decision to relocate to Brazil

was survival. When, in November 1807, courtiers scrambled aboard the fleet,

Napoleon's forces were on Portuguese soil storming towards the capital. Out off

the coast was a sizeable British navy, its cannons trained on the port.

Portuguese royalty had been caught up in the Napoleonic wars as the conflict

spread into the peninsula, and were in danger of being crushed by the two

superpowers of the age: Britain and France.

"Napoleon was intent on imposing a continent-wide trade blockade against the

British, and Portugal's ports had long served as British trading posts. Should

Portugal fall in line with Napoleon, Britain was prepared to bombard Lisbon and

destroy the Portuguese fleet (as they had done in neutral Copenhagen months

earlier).

"But the British, through their envoy Lord Strangford, were also backing the

wholesale removal of the court and government. In a secret convention signed a

month before the royal family set sail, the British agreed to escort the fleet

across the Atlantic in return for preferential trading rights in Brazil.

"Caught in the middle of all this was the Portuguese prince regent, Dom João

(ruling in place of his mad mother Maria), a man known for his indecisiveness.

As he dithered, events were rushing towards their climax. With the French army

closing in, the royal family, their ministers, nobles and servants a staggering

10,000 people in all clambered aboard the fleet, clearing port at the

eleventh-hour. After stopping off in Salvador, they eventually disembarked in

Rio de Janeiro, then the New World's largest slave-market town.

"There, in an unprecedented event in colonial history, they set up their court.

Up until that point no European royal family has ever visited the New World, let

alone tried to rule from the Americas. For the next 13 years Portugal and her

string of colonies fell under the sway of Rio de Janeiro, a slaving port

converted at a stroke into an imperial metropolis.

"What, perhaps, is a more intriguing question, is why they opted to stay in Rio

for such a long period. Napoleon was defeated by 1814 yet the court and

government to Portugal's chagrin - were still in Brazil half a decade later.

These, and many other questions, are explored in my book Empire Adrift, which

comes out later this year."

Patrick Wilken

pwilcken@yahoo.com

(From

here)