|

.

Cresci

a Sentir Que Era Uma Pessoa Má

ALEXANDRA

LUCAS COELHO

Violentos

como (auto)punhaladas, os poemas da indiana Eunice de Souza são uma

revelação. O apelido é português, a origem de Goa, a língua

inglesa. Em tradução de Ana Luísa Amaral.

Como

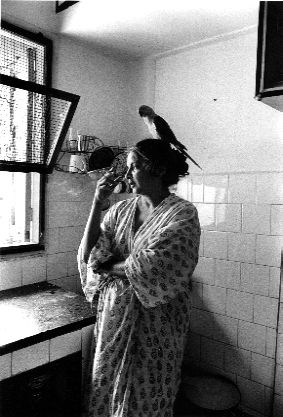

professora catedrática, "uma lenda implacável", como crítica

literária, "feroz", como poeta, simplesmente, "uma

das mais melhores da Índia, em língua inglesa". Sari de seda

cinza, olhos delineados a negro, Eunice de Souza, 60 anos, está

tranquilamente sentada para a quarta ou quinta entrevista da sua

primeira estadia em Portugal.

Também

autora de ficções para crianças e de antologias de mulheres

poetas indianas, esta descendente de goeses, educada na Índia britânica

(Poona e Bombaim) como uma brâmane católica, veio lançar

"Poemas Escolhidos", selecção a partir dos seus quatro

livros de poesia publicados.

Comparam-na

com Sylvia Plath? Talvez sem o arsenal lírico e com um punhal mais

agudo. Não meteu a cabeça no forno. Mas tentou morrer.

Surpreendeu-se a acordar na manhã seguinte. "Pensava que o

mundo inteiro / me tentava desfazer". Então descobriu:

"era isso o que eu queria / fazer ao mundo".

No

título de um dos seus poemas, avisa: "Não procures a minha

vida nestes poemas". Mas o que prevalece na sua poesia é um

registo autobiográfico, com referências à mãe, ao pai, a quem a

rodeou. É a sua vida. Claro. Escrevi esse título porque existe a

tendência na Índia para acreditar que se lemos os poemas de alguém

sabemos tudo sobre a sua vida. Mas as memórias são selectivas, e o

que tento dizer é que o poeta cria uma "persona". A vida

de cada um é muito caótica, e os poemas são uma ordem. A ironia,

a violência recorrentes nos seus poemas são acentuadas por essa

referencialidade autobiográfica. É de si que fala, cruamente, sem

complacência. O primeiro livro [no original, "Fix",

1979"] é muito violento. Isso vem da minha história pessoal.

Perdi o meu pai muito nova, com três anos.E escreve: " Pronto,

aí vem. / Matei o meu pai quando tinha três anos." Creio que

quando alguém próximo morre, uma criança se sente sempre culpada.

Cresci a sentir que era, de certa forma, uma pessoa má, de quem

ninguém podia gostar. O ambiente em casa, entre os meus avós, era

muito autoritário... O que lhe explicaram dessa morte? Nada. Depois

em relações amorosas tive sempre esse medo, de que ninguém

ficaria comigo. O que acontece quando se está assim superansioso

numa relação, é que se fazem muitos erros, e de facto as pessoas

acabam por partir... Em vários poemas, há quase uma auto-flagelação

- "Eu pertenço aos patos feios" ; "Estúpida vaca

sem soutien", "Estou fascinante de vermelho e negro / e

com um colar de caveiras"... Sobretudo nos dois primeiros

livros. No primeiro, a capa tem uma cruz sobre a minha cabeça...

... como um cerco sufocante em torno de uma rapariga que cresce, e

se sente deslocada o tempo todo. Sim. A minha comunidade, a dos católicos

goeses, era sufocante. Agora parece infantil, mas olhando para trás...

eu era sempre demasiado calada, ou demasiado baixa... não tinha irmãos,

quando o meu pai morreu fomos viver com os meus avós, em Poona,

cresci com pessoas muito mais velhas, tios e tias, não havia crianças.

Não conseguia encontrar ninguém da mesma natureza que eu, só

quando cresci tive gente com quem falar do que me interessava.

Passei a maior parte do tempo a ler, sozinha. O meu pai tinha umas

centenas de livros, incluindo uma selecção dos clássicos

ocidentais. Ele lia muito, julgo que estava a tentar ser um escritor

- trabalhava para o governo, quando eu era pequena vivíamos no

centro da Índia, foi aí que ele morreu, de uma doença incurável

a que chamavam febre da água negra. Um dia estava a arrumar as

coisas dele e encontrei um caderno de notas com contos e poemas. Os

contos eram bastante interessantes. Não sabia nada dele, e guardei

esse caderno até hoje. É nas referências à sua mãe que

encontramos alguns dos pontos mais brutais, como no remate de

"Perdoa-me, mãe": "Em sonhos / fustigo-te"

["I hack you, no original, ferir, cortar à machadada]. Era uma

relação muito ambivalente. Eu tinha algum medo dela, porque ela

era muito severa, mas também tinha pena. E um sentimento de protecção...

Nesse poema, parece haver uma espécie de entendimento tardio do que

ela sentiu, e afinal o fim é terrível. É como querer matar alguém

porque está demasiado na nossa vida, alguém de quem nos queremos

livrar. Depois, em "Ela e eu", há um fragmento de lirismo

pouco frequente na sua poesia, quando ela lhe fala do seu pai,

"dos / quadros que ele amava, / e um lugar esquecido / onde caíam

flores azuis". Nunca falávamos dele, nunca perguntei nada. Foi

como se o inventasse. Ele não me parece muito real, tenho muita

dificuldade ainda hoje em falar dele. É quase embaraçoso, tenho

que me forçar. Tenho a memória de alguém que me costumava sentar

nos joelhos, me levava a passear de elefante, e eu não sabia quem

era, só que não era nenhum dos meus tios. Em vários poemas, faz

uma síntese do silêncio e exclusão das mulheres da sua

comunidade. Como: "Pilar da Igreja / diz o padre da paróquia /

Que Linda Família Católica / diz a Madre Superiora // a mulher do

pilar / não diz nada." Eu não conhecia a palavra feminismo. Só

sentia fúria. As mulheres não tinham controle sobre a natalidade,

casavam muito cedo, como a minha avó, com 14 anos, esperava-se

delas que tivessem muitos filhos. Foi só com vinte e tal anos que

percebi que muitos dos meus poemas eram de alguma forma feministas.

A

maior parte das mulheres que conheço são muito mais fortes que os

homens, mais maduras, mais pacientes. Os homens são tão mimados

desde jovens que se tornam infantis. As mulheres obedecem-lhes e

ouvem-nos, mas da mesma forma que lidariam com uma criança. E

quando se tornam viúvas, florescem, tornam-se mais alegres, são

livres. Vi isso na minha família, mulheres deprimidas durante anos

que, quando os maridos morrem, se tornam felizes. Diria que nos últimos

20, 30 anos, houve uma evolução na forma como as jovens são

educadas? Vi nas minhas alunas que muitas não queriam casar cedo.

Uma contou-me que o seu noivado fora rompido, e que a forma que

encontrou para lidar com isso foi ler os meus poemas, sentiu que não

era uma desonra assim tão grande. Eu não sou casada, conduzo a

minha vida, de certa forma, com sucesso, é como se fosse uma outra

possibilidade para elas. Uma das mulheres do livro é a sua tia

"educada à portuguesa" que "pegou num shivalingam de

barro / e disse: / É um cinzeiro? Não, disse o vendedor, / É o

nosso Deus." Breve e devastador. O que era ser "educada à

portuguesa? Quis mostrar duas culturas que coexistem e não se

entendem. Antes de Goa voltar para a Índia, para os goeses,

indianos eram os que estavam na Índia, desconfiavam de quem usasse

sari, de quem não falasse português. Entretanto, quando cresci,

descobri que a minha comunidade católica também desprezava os

indianos hindus. E, no entanto, tínhamos o mesmo sistema de castas,

e uma brâmane católica não casa com católicos de outras

castas... O que conhece da língua portuguesa? Quase nada. O meu avô

costumava usar a palavra "malcriado", quando estava

aborrecido com alguém. Também me lembro de...

"sossegado"...? A minha família converteu-se do hinduísmo

ao catolicismo, provavelmente no século XVII. Com a inquisição em

Goa, muita gente foi forçada a isso, por medo. Quem converteu a

minha família, deu-lhe o apelido de Souza, então muito comum.

Muitos goeses foram partindo para a Índia britânica, os meus avós,

de ambos os lados, também. Quando eu era pequena, só voltávamos a

Goa nas férias grandes.

Suplemento

Mil Folhas, PÚBLICO, 14 de Abril de 2001

|