8-6-2004

Contrabando y Traición

|

Contrabando

y Traición

Hear the music

Salieron de San Isidro

Procedentes

de Tijuana,

Traían las

Ilantas del carro

Repletas de

yerba mala.

Eran Emilio

Varela

Y Camelia

La Tejana.

Pasaron por

San Clemente

Los paró la

emigración,

Les pidió

sus documentos,

Les dijo

"De donde son?"

Ella era de

San Antonio

Una hembra

de corazón.

CHORUS 1:

Una hembra

si quiere a un hombre

Por el

puede dar la vida,

Pero hay

que tener cuidado

Si esa

hembra se siente herida,

La traición

y el contrabando

Son cosas

incompartidas.

A Los

Angeles llegaron

A Hollywood

se pasaron

En un

callejón oscuro

Las cuatro

Ilantas cambiaron,

Ahí

entregaron la yerba

Y ahí

también les pagaron,

Emilio dice

a Camelia:

"Hoy te das

por despedida.

Con la

parte que te toca

Tu puedes

rehacer tu vida,

Yo me voy

pa' San Francisco

Con la

dueña de mi vida."

CHORUS 2:

Sonaron

siete balazos

Camelia a

Emilio mataba,

La policia

solo halló

Una pistola

tirada.

Del dinero y

de Camelia

Nunca mas

se supo nada.

Angel Gonzalez

cantan: Los

Tigres del Norte

|

Smuggling and Betrayal

They

left San Isidro, coming

from

Tijuana,

They had

their car tires full of

"bad

grass," (marijuana)

They

were Emilio Varela and

Camelia

the Texan.

Passing

through San Clemente,

they

were stopped by

Immigration.

He asked

for their documents,

he said,

"Where are you from?"

She was

from San Antonio,

a woman

with a lot of heart.

A woman

so loves a man that

she can

give her life for him.

But

watch out if that woman

feels

wounded,

Betrayal

and smuggling do not

mix.

They

arrived in Los Angeles,

they

went to Hollywood.

In a

dark alley they changed

the

tires.

There

they delivered the grass,

and

there also they were paid.

Emilio

says to Camelia, "Today

is your

farewell,

With

your share you can make a

new

life.

I am

going to San Francisco

with the

mistress of my life."

Seven

shots rang out, Camelia

killed

Emilio.

All the

police found was the

discarded pistol

Of

Camelia and the money

nothing

more was ever known.

|

|

Contrabando

Y Traicion (Smuggling and Betrayal) (drug smuggling song)

Sing

Out! The Folk Song Magazine, Spring,

2002, by Elijah

Wald,

Angel Gonzalez

This song was composed by Angel Gonzalez around 1970. It

is his only corrido, though he has written quite a few other ranchera hits.

He says that the story is fictitious, but that many similar things were

happening around that time, and he gives the credit for its success to its

dynamic heroine: "I am a feminist, five hundred percent," Gonzalez says.

"Woman is half the world, and what's more she's the mother of the other half

In my songs, I always have the woman come out ahead. `Contrabando y Traicion'

was the first song like that, and then, it was also the first song about the

drug traffic. There was nothing like it."

In fact, there had been occasional drug smuggling songs

recorded since the time of the bootleggers, but this is the song that

sparked the narcocorrido boom, and made Los Tigres Del Norte into stars.

This song was made into a movie, spawned several sequels, and is known to

virtually every Mexican and Mexican-American (though usually by the name "Camelia

La Tejana, "rather than its official title). |

|

|

|

Nov. 5, 2002, 9:29AM

LATIN MUSIC

Los Tigres' influence comes

full circle

Los Tigres del Norte's influence

and cultural impact have hit a new, unexpected milestone: One of the band's hits

has inspired a popular novel in Europe.

Spanish author Arturo

Pérez-Reverte wrote La Reina del Sur (Alfaguara, $19.95 paperback) about

drug trafficker Teresa Mendoza, a character inspired by Camelia la Tejana, the

protagonist of Los Tigres' seminal 1972 hit Contrabando y Traición.

When Los Tigres read the book,

they liked what they saw.

"The author researched the

characters for La Reina del Sur very well," vocalist Jorge Hernandez

says. "It's a very realistic story."

Now the norteño kings return the

favor by recording La Reina del Sur. The corrido is the title cut

of its new album, out Tuesday.

While the idea of Los Tigres

recording a song based on a book based on one of its songs may seem odd,

Hernandez says the move could help them enter new markets. The group toured

Spain last year.

"He (Pérez-Reverte) has a lot of

readers in Europe," Hernandez says. "It's a market we want to reach, and we got

together with him to do this production."

Plans are to turn the book into

a movie, Hernandez says, "so we could be doing the soundtrack."

While it could help Los Tigres

reach new audiences, the song, written by longtime collaborator Teodoro Bello,

lacks the action and intrigue that made Contrabando y Traición a classic

among corrido aficionados.

The album includes a couple of

political songs as well. "There's a song called El Soldado that's about

war," Hernandez says. "The father raises his son in a certain way in the United

States, or anywhere, and the government calls him up and trains him to kill, and

the father suffers because his son has to go off. But that's the son's desire.

That's something we're living right now.

"We wondered how to comment on

the war now and the problems with (Osama) bin Laden. We got the idea of doing

something about soldiers, because there must be many parents in that situation.

We called (songwriter) Enrique Valencia to do that song."

Valencia was a good choice for a

song about intergenerational conflict, having written Los Tigres' hit Mi

Sangre Prisionera in which a father laments years of inattentiveness toward

his now delinquent son.

But overall, La Reina del Sur

has a lighter touch than its predecessors.

Los Tigres' 2001 CD Uniendo Fronteras spent

three weeks at No. 1 on the Billboard Latin Albums chart and spun off the

singles Mi Fantasía, De Rama en Rama, Somos Más Americanos and

Recuerdos Que Duelen.

But the song that generated the

most controversy was Crónica de un Cambio. Recorded a few months after

Vicente Fox's inauguration as president of Mexico, the song detailed problems he

inherited from previous governments and asked when change was coming.

However, Crónica wasn't

released to Mexican radio until July 2002, causing the social commentary to be

misinterpreted as a criticism of Fox's administration. Fearful of offending the

federal government, a major advertiser in Mexico, most stations nixed the song.

Ramiro Burr covers the Latin

music scene each week.

www.fuoriluogo.it

Nuova Serie, Anno 4, Numero

6, Giugno 2002

Messico e

nuvole

Il‘narcocorrido’ è una degenerazione della tradizione musicale popolare, un nuovo

genere nato per narrare le gesta e le battaglie del Messico attuale e dei narcotrafficanti. Molte delle canzoni mantengono lo stile classico delle ballate

e delle romanze del corrido (così definito per la velocità del ritmo, segnato

quasi sempre da una fisarmonica) e rappresentano un vincolo anacronistico tra le

tradizioni poetiche più antiche europee e il mondo del ‘gangsta rap’, della

cocaina e del crack.

Le bande adottano il punto di vista degli emarginati e questo forse spiega la loro grande

popolarità, maggiore della salsa e del pop tropicale di Miami, oltreché in

Messico anche tra la comunità ispanica negli Usa, di cui fanno parte più di tre

milioni di clandestini messicani. Originario degli Stati settentrionali

messicani, il narcocorrido si è diffuso lentamente in tutto il Paese, tanto che

il governo ne ha recentemente vietato la diffusione radio e tv su tutto il

territorio nazionale nel tentativo di bloccarne la crescente popolarità,

specialmente tra i giovani. Ma per trovare un cd o un nastro di narcocorrido

basta andare in qualsiasi mercatino di città o di paese. E il successo del

genere è evidenziato anche dalla grande quantità di copie contraffatte in

circolazione. Il linguaggio dei testi è quello gergale dei narcotrafficanti,

sospettati di sponsorizzare alcuni gruppi di narcocorrido. Il sospetto delle

autorità messicane è che i narcos si servano del narcocorrido per far

credere alla popolazione di essere i benefattori di quella larga fascia di

emarginati dimenticata dallo stato. E di investire una fetta degli ingenti

proventi del traffico di droga in opere sociali.

November 6 – 12, 1998

Corridos Prohibidos

Los Tigres del Norte, Idolos del Pueblo

by Sam Quinones

GUAMUCHIL,

Mexico - By now it is very close to 4 a.m.

on the outfield of the Garbanceros - the Garbanzo-Bean Growers - the baseball team for the town of

Guamuchil (population about 100,000), not far from the Pacific Ocean in the

state of Sinaloa. Los Tigres del Norte are dressed in the sweetest

turquoise-satin suits you've ever seen, with white fringe to make David Crosby

green with envy, and are bouncing through "El Avion de la Muerte" ("The Airplane

of Death").

The song is about a man whom soldiers take up in an airplane and torture. He

disarms one of them, takes control of the plane and decides to crash it into a

military barracks on a hill in the distance. On the hill, he sees a school and

children at play. So he pulls the plane up and smashes it instead into a hill

farther away, killing himself and his torturers, who go to their deaths reduced

to tears.

Now that's the kind of thing songs should be written about. It's a true story.

The whole event was taped by an airport control tower.

And about now, on the Garbanceros' outfield, groups of staggering, short-haired

young men in white cowboy hats, silk shirts and cowboy boots are feeling the

song's sublime message. They hold each other upright in full-grip handshakes

that take a good 10 seconds in the wind-up and consummation. Heads to the sky,

faces contorted, they chortle along with Jorge Hernandez, Los Tigres' lead

singer.

At stagefront, hundreds of young people, primarily teenage girls, stand crushed

against each other, mouthing lyrics to a song recorded when most of them were in

elementary school. Farther back, on the infield, couples grapple in various

stages of consent as they rock to and fro with the polka beat.

And this moment, as the band tells this story of humiliation and revenge, as

young men bond, young women squeal and young couples explore each other on a

baseball field in a small town in a corner of Mexico - this moment you are

getting close to the essence of Los Tigres del Norte, the most important and

enduring binational band in pop music.

Los Tigres have played dances for 100,000 people in Los Angeles, Monterrey and

Guatemala City. So this crowd of about 3,000 people is small by Tigres

standards. Yet the band plays Guamuchil every year. It is a homecoming. Los

Tigres grew up in Rosa Morada, a village of unpaved streets half an hour from

here. Playing dates like this is one way the band shows that they remember who

they are, where they came from, and that no matter how long they live in

America's decadent gut, they remain mexicanos, cien porciento.

Los Tigres del Norte - four brothers, a cousin and a friend - are the

Mexican-immigrant experience personified. Like thousands of immigrants, they

crossed the border, made it in America, but never shed their most precious

commodity, their mexicanidad - their Mexicanness. Like the Mexican-immigrant

community, they are virtually unknown to American society at large. Within it,

they are revered - Los Idolos del Pueblo.

This year marks the band's 30th anniversary. They have made 30 records and 14

movies, won a Grammy and were nominated for another this year, and have played

thousands of dances on both sides of the border.

Los Tigres have twice created trends in Mexican pop music, first with songs

about drug smuggling and, later, about immigration. Immigrants, in turn,

transported Tigres' music to parts of Mexico where the band was unknown. Los

Tigres' audience now stretches across the United States, and down to the states

of Michoacan and Guerrero, and into Guatemala, El Salvador and Nicaragua.

Together, the band and its public turned norteno into an international genre.

Meanwhile, the band modernized the music, infusing it with boleros, cumbias,

rock rhythms and waltzes, sound effects of machine guns and sirens, better

recording quality. In the process they made a pop style out of an

accordion-based polka music indigenous to northern-Mexico cantinas.

Los Tigres emerged from an unnoticed side of the 1960s. As America's restless

children were turning in rebellion to drugs and music, restless working-class

Mexicans began coming to the United States. Their exodus was also a rebellion of

sorts, if unarticulated and unpublicized. Mexico's young were leaving corrupt

Mexico - the Mexico behind the sunglasses, the Mexico that never gave a poor man

a chance - eager to re-create themselves in the fields and restaurants of

Gringolandia. The irony was that in Gringolandia these immigrants wanted more

than ever to be Mexican. They missed the pueblo, the girlfriend, Mom. Mostly

they asked from the U.S. what Mexico had never allowed them - a chance to earn

real money for hard work, to progresar.

As these immigrants grew into one of the most significant movements of people in

the last half-century, Los Tigres became their chroniclers, spokesmen for a

community that remains largely voiceless in both Mexico and the U.S. If you want

to know what the Mexican-immigrant community is feeling, listen to a Tigres

record. Their audience is your gardener and grocer, your car washer, your

busboy.

Tigres' best songs are stories distilling the essentials of Mexican

working-class life: brutal machismo, piercing irony and the tenderest melodrama

- the honest cardsharp who, down to nothing in a poker game, bets his beautiful

young bride, loses her and pays his debt by shooting her, then killing himself;

the man who keeps a grave at the cemetery so his children will believe their

mother died instead of running off with another man; the three inseparable drug

smugglers who, surrounded by the DEA, blow themselves up with a grenade; the

immigrant who leaves his young brother in the care of his fiancee to support the

brother's education, only to return and find the brother has married his

fiancee.

In 1968, the band - four kids - arrived at the border in Tijuana with a musical

revue contracted to play for two dates: one, the September 16 Mexican

Independence Day parade in San Jose; the other, for inmates at Soledad. Since

the oldest was only 14, they had to persuade a middle-aged Mexican couple to

pretend to be their mother and father. The band had no name. But the immigration

officer kept calling them "little tigers," and they were headed north and

playing norteno music, so they became Los Tigres del Norte.

Los Tigres never returned to Mexico to live. They stayed in San Jose and played

small clubs, furniture-store openings and weddings for the Bay Area's growing

Mexican community. They once shared a Berkeley festival bill with Big Mama

Thornton and Janis Joplin, talking with the latter backstage as she and her band

wolfed down apples that made them act funny. They might have remained just

another cantina band were it not for a song that changed the group and norteno

forever. Jorge Hernandez, the oldest brother, heard the song in an L.A.

nightclub.

Los Tigres put out their version of that song, "Contrabando y Traicion"

("Contraband and Betrayal") in 1972. It tells the story of a man and a woman -

he an illegal, she a Chicana from Texas - smuggling marijuana from Tijuana to

Los Angeles. After exchanging the dope, the man says he's taking his money and

visiting his girlfriend in San Francisco. However, his partner is in love with

him. Unwilling to share him with another, she shoots him in a dark Hollywood

alley and disappears with the cash.

The song beautifully fuses news item and twisted love story into a series of

images that end in sweet tragedy. "It was like a film in the mind's eye," says

Hernandez, the band's accordionist, lead singer and musical director. "And it

was the truth of what was happening in those years. It came out at exactly the

right moment. It spoke of the total chaos that is drug trafficking. Perhaps,

also, people had never heard these things said so clearly in song."

By now America's youth was getting high in large numbers, and Mexican immigrants

were seeing drug trafficking daily as they crossed the border. The song hit

huge. "Contrabando" is now a norteno classic, and two sequels followed. Dozens

of lesser-known bands have recorded it. Its two characters, Emilio Varela and

Camelia La Tejana, are part of the Mexican cultural vocabulary.

The tune launched Los Tigres' career. But beyond that, "Contrabando" was the

first hit about drug smuggling. a Los Tigres followed it with another, "La Banda

del Carro Rojo" ("The Red-Car Gang"). Together those songs revealed a market and

essentially created the narcocorrido, currently undergoing an explosion in

popularity in Mexican music.

The narcocorrido updated the traditional corrido, or ballad, which told of

revolutionaries, bandits or a famous cockfight. Instead, narcocorridos tell of

drug smugglers, shootouts between narcos and police, betrayals and executions -

bloody events set to a rollicking polka rhythm and an obliviously cheerful

accordion line. Almost any norteno band nowadays plays a few narcocorridos.

Hundreds of bands play nothing but. Narcocorridos are Mexico's gangster rap.

Both musics recount horrible violence; both receive virtually no radio support

and nonetheless maintain enormous audiences.

Catholic Church spokesmen and Mexico's center-right National Action Party have

criticized the narcocorrido phenomenon, and the groups that play them, as part

of "the culture of death."

"The only thing that we do is sing about what happens every day," Hernandez

says. "We're interpreters, then the public decides what songs they like."

The public has long decided it likes the dope songs. For many years, the band

included two or three on each album. In 1989, they put out Corridos Prohibidos

(Prohibited Corridos), an entire album about drug smuggling. It was the first of

its kind on a major label; there were reports that narcos were buying the record

by the case. One of the songs dealt with the 1988 murder of Hector "El Gato"

Felix, a muckraking columnist for the Tijuana newsweekly Zeta, who had angered

many in Baja California politics. Tijuana radio stations refused to play the

song, until Zeta raised hell.

Still, Los Tigres have tried mightily to distance themselves from the hundreds

of cookie-cutter narcobands that have sprouted over the last 20 years. Their

repertoire has always been at least half love songs. "Un Dia a la Vez" ("One Day

at a Time"), a quasi- religious tune, responded to the growing influence of

fundamentalist Protestant churches within the Mexican-immigrant community in the

mid-1980s - churches that condemned dancing and singing as indecent. They won

their Grammy for "America," a rock anthem expounding the universal brotherhood

of all Latins.

Los Tigres reside by choice on the tamer side of the narco genre. Unlike the

younger bands who followed them, they only occasionally mention the names of

real drug smugglers, are never photographed with pistols or assault rifles,

never curse in a song, and usually refer to marijuana and cocaine as "hierba

mala" or "coca."

Other bands have allegedly received narco sponsorship. A drug informant, during

an interrogation with police that was later published by a Mexican newsweekly,

said Los Tucanes de Tijuana, one of the hottest narcobands, was sponsored by

Benjamin Arellano Felix, leader of the Arellano Felix drug cartel.

In 1994, members of Los Huracanes del Norte were hurt in Guadalajara when a bomb

exploded at a party they were playing for a family member of Rafael Caro

Quintero, the imprisoned drug lord convicted of murdering DEA agent Enrique

Camarena in 1985.

"[Narcos] have sent me letters, notes," says Hernandez. "They invited us to

meetings years ago. We've never had the opportunity, nor wanted to meet them.

We've made our career in public, not at [private] parties."

Los Tigres' explorations of the narco theme brought them fame. But the band

earned a lasting transcendence when its songs began reflecting immigrants'

conflicted feelings regarding Mexico and their new home.

At a dance in the mid-1970s, it dawned on Hernandez that many of the illegal

immigrants hung back. They didn't laugh and shout as easily as those with legal

papers. In 1976, the band put out "Vivan los Mojados" ("Long Live the

Wetbacks"), an anthem to illegals that wonders what would happen to California's

crops if all the mojados suddenly disappeared. Within the Mexican-immigrant

community, the reaction to the song was electric. "That's when we realized that

there was a market for this," Hernandez says. "We began to see that we needed to

communicate with them."

In the early 1980s, Los Tigres hired as producer Enrique Franco, a musician and

composer, who had just arrived from Tijuana. Franco gave them some of their most

enduring and bittersweet songs on the immigration theme: "Pedro y Pablo," "El

Otro Mexico," "El Bi-lingue," "Los Hijos de Hernandez" - all dealing with the

wrenching dilemmas of immigrant life, with separation, love lost, the yearning

to return home and the economic importance of immigrant labor.

In 1988, as war was sending thousands of Central American immigrants to the

U.S., Franco wrote "Tres Veces Mojado" ("Three Times a Wetback"), a story of a

Salvadoran refugee who crosses three borders to get to America. But "La Jaula de

Oro" ("The Gold Cage"), Franco's greatest immigration song, was recorded in

1984. "Vivan los Mojados" had created a boom in novelty songs about immigrants,

songs that generally were about the zany hijinks of wacky immigrants outfoxing

the dull-witted migra. "[Immigration] had never been treated as a social

problem," says Franco, now a record producer in San Jose. "I was illegal at the

time. I never had the problem of communication with my children, but many

immigrants do. There isn't time to talk to the kids. The children learn another

language. That's where the gap between kids and parents begins."

"La Jaula de Oro" is told by an immigrant years after he outwits the migra. He's

discovered he doesn't feel at home in the country he tried so hard to enter.

Even worse, his children now speak English and reject their mexicanidad. And

though he aches to return home, he can't leave his house for fear he'll be

deported.

The U.S. is a "gold cage," says Hernandez. "You have everything. You live well,

you have comforts. But it's another type of life, very different from ours. The

United States is very solitary. And you can't relax, like in Mexico. There's not

a lot of heart in the family."

Through the early 1990s, Los Tigres recorded fewer narcocorridos and immigration

songs. But the nature of current events returned a harder thematic edge to Los

Tigres' music. In 1995, they recorded "El Circo" ("The Circus"), about former

President Carlos Salinas de Gortari and his brother Raul, now in prison on

murder and money-laundering charges. Radio stations, still unsure how government

censors felt about the issue, refused to play the song until a news anchor began

putting it on his morning show.

The band's latest album, Jefe de Jefes (Boss of Bosses) - the first double album

in norteno history and for which Los Tigres were nominated for a Grammy this

year - is more clouded than ever by the headlines. The title song is about a

fictional drug lord, and the album includes several narcocorridos, including one

about Sinaloa drug-cartel leader Hector "El Guero" Palma, arrested after a plane

crash in 1996. "El Prisionero" is about the recent political assassinations in

Mexico. "El General" deals with General Jesus Gutierrez Rebollo, who was

arrested in February, accused of being in the pay of the Juarez drug cartel.

And in the midst of heightened anti-immigrant sentiment in the U.S., Los Tigres

again touches the concerns of its most important audience. "El Mojado Acaudalado"

("The Wealthy Wetback") is a song about those who've made it in the U.S. but no

longer feel comfortable here, and now are going home with heads held high. "Mis

Dos Patrias" ("My Two Countries") has a naturalizing Mexican insisting that he

is not a traitor to his flag, that he's only protecting his pension.

But it is another ballad that perhaps best sums up the feelings of immigrants

these days. "Ni Aqui Ni Alla" ("Neither Here nor There") is doused in the

pessimism brought on by America's anti-immigrant atmosphere and Mexico's

economic crisis and corruption scandals. The song doubts immigrants' chances of

receiving justice and, finally, of being able to progresar on either side of the

border: "Wherever you go, it's the same. My dreams, neither here nor there, will

I ever realize."

It is a philosophical U-turn for a band whose music and career were founded,

like the Mexican-immigrant community itself, on a healthy optimism and belief in

the healing powers of hard work.

"You have to tell the truth - we're not good here or there," says Hernandez.

"Anytime a Mexican does something good in the United States, there's someone

waiting to take it away from him. You never know if, making money and living

right, you're going to make it."

Jueves, 31 de enero de 2002 - 04:49 GMT

Tiro de gracia a los narcocorridos

El gobierno de Chihuaha prefiere que se promuevan otros valores más positivos.

Escribe la corresponsal de la BBC en México, Elva Narcia

"Salieron de San Ysidro, procedentes de Tijuana,/

Traían las llantas del carro repletas de hierba mala,/ Eran Emilio

Varela y Camelia la Tejana".

Así comienza la canción que inició el auge de la música del llamado

narco-corrido, allá por el año 1972.

El

tema se llama "Contrabando y traición" y habla de un par de traficantes, Emilio

y Camelia, que emprenden un viaje, con las llantas de su auto llenas de

marihuana, hasta encontrarse con un destino imprevisto.

Canciones como esa no podrán difundirse a partir de ahora en las estaciones de

radio del estado fronterizo de Chihuahua, luego de un decreto aprobado esta

semana por la Sexagésima Legislatura de esa entidad federativa.

El

dictamen emitido por el Congreso de ese estado invita "atentamente" a los

radiodifusores a evitar la transmisión de esos temas musicales pues "a fuerza de

escuchar reiteradamente que los delincuentes son superhéroes, que cuentan con

dinero a manos llenas y que carecen de privaciones, a través de las cintas o

discos que se escuchan por medio de las radiodifusoras, los niños y jóvenes

pierden el interés en el estudio, trabajo y valores familiares, para ambicionar

el dinero fácil, la depravación y los vicios".

"Perjuicio directo a la sociedad"

La

iniciativa fue promovida por el diputado Oscar González Luna, integrante del

Grupo Parlamentario del Partido Acción Nacional.

El

legislador expuso que los narco-corridos "difunden una forma de vida, de

hábitos, costumbres y valores, como lealtad, religión y valentía, por lo que la

niñez y juventud en general pretenden imitar estos patrones de conducta, que

definitivamente a corto, mediano y largo plazo, ocasionan un perjuicio directo a

la sociedad".

Asegura que las letras de las canciones que se trasmiten por las radiodifusoras

a nivel estatal hablan de sucesos que tienen que ver con los narcotraficantes,

secuestradores, lenones, homicidas y violadores, entre otros delincuentes.

"En ellas se hace alusión a la identidad de los sujetos, mismos que demuestran

una manera especial de vestirse, enjoyarse, de hablar e incluso en sus pueblos o

ciudades natales son muy populares y aceptados, ya que en muchas de las

ocasiones cubren las necesidades de la población, como las de obras públicas,

vivienda y empleos", agrega.

El

dictamen del congreso de Chihuahua dice textualmente que el estado debe ejercer

su obligación de proteger a la sociedad y vigilar que la ley se cumpla,

procurando siempre hacerlo en su justa dimensión, con medidas de restricción

para que estos productos no sean transmitidos masivamente a través de una

frecuencia que, como bien nacional, debe operar bajo los principios del interés

público y el bien común.

"Sonaron siete balazos, Camelia a Emilio mataba,/

La policía sólo halló una pistola tirada,/ Del dinero y de Camelia

nunca más se supo nada".

N Z Z

Online

7. Januar 2004, 06:17, Neue Zürcher Zeitung

Schauplatz Mexiko

Das Lied des Banditen

Die seltsame Karriere des «Narcocorrido»

Subversion ist

von jeher Bestandteil mexikanischer Kultur. Bewundert im Volk, verkörpert der

Bandit, ob gut oder schlecht, den Widerpart übermächtiger Institutionen. Heute

sind es vor allem die Drogenbosse, die die anarchistische Phantasie bereichern.

Seit kurzem macht im Musikgeschäft der «Narcocorrido», das Lied der Drogen,

Karriere.

Am Stadtrand von

Culiacán steht eine Kapelle. Einst war sie kleiner, lag an einem anderen Ort,

angeblich über den Gebeinen des heiligen Malverde. Doch war sie dort den

mexikanischen Behörden ein Dorn im Auge. Sie sollte weg und mit ihr das Gedenken

an eine Figur, die von der Kirche nie ihr Sanctum erhalten hat. Ein Sturm des

Protests brach los. Also traf man eine mexikanische Entscheidung, surreal und

merkwürdig. Man riss sie ab und baute eine neue, schönere.

«Er war ein

Bandit, aber niemals ein Mörder / wenn er stahl, dann aus Not», erzählen die

Corridos die mexikanische Version von Robin Hood. Er teilte sein Geld mit den

Armen, behaupten die einen; bösere Zungen spotten, dass er mit seiner Beute die

Tavernen am Leben erhielt. Auch schön. Malverdes Mut und Dreistigkeit machten

vor niemandem Halt - auch nicht vor dem Staat. So verwundert es nicht, dass

seine Taten ihn zum Heiligen der Drogenkönige machten. Und zum Patron ihrer

Chronisten, der Corridistas.

Die Stimme derer ohne Stimme

Geschichte, im

zweifachen Sinne, bewegt den Mexikaner von jeher. Sie wird erzählt, mythisiert

und am liebsten gesungen. Seit mehr als einem Jahrhundert sind die Corridos eine

musikalische Zeitung für das einfache Volk, die Stimme derjenigen, die keine

Stimme haben. Die Ursprünge des Corridos sind ungesichert, ein ewiger Streitfall

unter Musikologen. Nationalisten verankern ihn in der aztekischen Kultur. Die

Vermutung liegt näher, dass er mit den spanischen Eroberern und der Tradition

der Romanze ins Land zog. Mit den Jahren wird aus einer elitären Gedichtform ein

episch-narratives Volksgut, den Botschaften der fahrenden Sänger des

Mittelalters viel näher als dem normativen Regelwerk der Romanze.

Seinen ersten

Höhepunkt erlebt der Corrido zu Zeiten der mexikanischen Revolution. So viele

Schlachten und Helden verlangen nach Verklärung. Also werden ihre Taten in die

kleinsten Dörfer getragen, auf Märkten rezitiert, interpretiert und nicht mehr

vergessen. Zumeist begleitet die Corridistas eine Gitarre, und zuweilen gibt es

die Lieder, auf Zettel gedruckt, für ein paar Centavos zu kaufen. Doch bleibt

der Vortrag stets wichtiger. Zu viele Dörfler können nicht lesen und erfahren so

von den Taten Villas und Zapatas, ihren Zügen in die Stadt Mexiko und ihrem

tragischen Ende.

Heute, in den

Zeiten des globalen Dorfes, feiert der Corrido seine Auferstehung. Die

multimediale Welt, so könnte man glauben, braucht keine Minnesänger mehr.

Alphabetisierungswellen überschwemmen Mexiko, und Fernseher müssten für den Rest

sorgen. Den Veränderungen der Welt setzt der Corrido seine eigenen Innovationen

entgegen, bleibt sich dabei stets treu und fühlt den Puls der Zeit. Die

vorgeschriebenen Koordinaten, das Reimschema und die meist vierzeiligen

Strophen, werden gedehnt. Der Inhalt allerdings erfährt eine elementare

Verschiebung. Der klassische Gesang vom heroischen Banditen, vom Rebellen mit

gutem Grund, wird ersetzt. Heute sind es vor allem die Drogenbosse, die die

mexikanische(n) Geschichte(n) bereichern.

Die Subversion

ist von jeher Bestandteil mexikanischer Kultur. Bewundert im Volk, verkörpert

der Bandit, ob gut oder schlecht, den Widerpart übermächtiger Institutionen. Er

bietet dem korrupten Staat die Stirn und verweigert das Vorrecht

US-amerikanischer Einflussnahme. Sein revolutionäres Potenzial ist zwar

verloren, seine Taten jedoch sind manifest. «Sie kamen von San Isidro / wohnhaft

in Tijuana / die Reifen des Wagens / gefüllt mit Marihuana.» Die Anfangszeilen

in «Contrabando y Traición» von Los Tigres del Norte, harmlos auf den ersten

Blick, stellen eine Revolution im mexikanischen Musikgeschäft dar. Dem Corrido

wird fortan ein «Narco» vorangestellt, ein untrügliches Zeichen dafür, dass es

sich um das Lied der Drogen handelt. In einigen mexikanischen Regionen ist das

nicht mehr als eine Tautologie. Kein Wunder. Mexiko gilt als wichtigstes

Transitland für kolumbianisches Kokain und ist selbst unter den Marktführern im

Heroin- und Marihuanahandel. Die Drogenkartelle sind mächtig. Doch blieben ihre

Taten geheim. Mit dem Narcocorrido ändert sich das. Die Illegalität bekommt eine

Stimme.

Das erste grosse

Zentrum des Narcocorrido liegt allerdings nicht auf mexikanischem Territorium,

sondern in Los Angeles, der grössten mexikanischen «Enklave» in den USA. Nicht

Merengue oder Salsa sind gefragt, vielmehr sind es die neuen Töne aus dem

eigenen Süden. Ausgegrenzt und oft illegal leben Hunderttausende Mexikaner in

den Vororten und hören in den neuen Liedern vom Scheitern amerikanischer

Grenzkontrollen, von Schiessereien auf offener Strasse, dem Schicksal kleiner

Dealer - und vom grossen Geld ihrer Bosse, die oft aus denselben Bergdörfern der

Sierra stammen wie sie selbst. Die klein angefangen haben und die nun in Liedern

besungen werden. Das Band der Identifikation ist schnell geknüpft. Die

Verkaufszahlen steigen und werden in wenigen Jahren zur Industrie.

Der Corrido

verlangt Authentizität, und so verwundert es nicht, dass sich ein zweites

wesentliches Initial seines Erfolgs der fast mythischen Realität eines

Interpreten verdankt. Waren früher die Corridos bekannt, so waren es ihre Sänger

keineswegs. Mit Chalino Sánchez ändert sich die Geschichte. Aufgrund eines

Rachemordes flieht er aus seinem Dorf über die Grenze. Wenig später wird sein

Bruder erschossen, dem er im Gefängnis seinen ersten Corrido widmet. Erste

Platten erscheinen, auf denen Chalino stets martialisch mit Pistole, Halfter und

Gurt erscheint. Utensilien, die er auch bei seinen Konzerten trägt. In weiser

Voraussicht: Als im Mai 1992 ein Besucher auf die Bühne springt und losschiesst,

schiesst Chalino zurück. Er bekommt einen Streifschuss ab, sein Kontrahent

allerdings wird - jedoch nicht durch Chalinos Kugeln getötet - von der Bühne

getragen. Dem tragischen Zwischenfall folgen ungeheure Verkaufszahlen - und

natürlich Corridos über den Corridista selbst. Das früher anonyme Gewerbe wird

zum Sprungbrett junger Gruppen: Los Tigres del Norte, Los Tucanes de Tijuana, Grupo Exterminador, El As de la Sierra klettern an die Spitzen der Charts. Viele

davon mit tatkräftiger Unterstützung der Drogenbarone.

Nicht schön, aber wahr

Längst ist der

Narcocorrido in seine Heimat zurückgekehrt. Kein leichtes Unterfangen. In

einigen Bundesstaaten ist die Ausstrahlung der Drogengesänge verboten. Sie

kursieren unter der Hand. Ihre Ankündigung ist zuweilen skurril. Der

Radio-Boykott macht die Verbreitung schwierig. Also produzieren die meisten

Corridistas auch Liebeslieder, ein Code für das gleichzeitige Erscheinen ihrer

Narcocorridos. Der Dunkelheit wird wie immer mehr Aufmerksamkeit geschenkt als

dem Licht. Mit Recht. Zwar sind die Corridos zuweilen eine abstruse Mischung aus

anachronistischem Akkordeon-Geschramme und gangsta rap, doch lassen sie auch

tiefe Einblicke in die Mysterien des narkotisierten Untergrunds zu. Der Stoff

liegt auf der Strasse. Der Narcocorrido ist kein schönes Genre, aber der

Wahrheit oft sehr nahe - und eines, bei dem man vorsichtig sein muss. In einer

Welt, in der der Tod eine gewichtige Rolle spielt, lebt man auch als

Liedermacher gefährlich, wenn man die falschen Worte findet.

Den Kartellen

scheinen sie zu gefallen. So bieten sie Schutz für ihre Barden und lassen sich,

oft für mehrere tausend Dollar, Lieder für die Ewigkeit schreiben. Es finden

sich Corridos über Caro Quintero, einst Boss seines Kartells und heute einer der

wenigen grossen Gefangenen der mexikanischen Justiz. Oder über Rafael Arellano

Félix, der nach offizieller Meinung tot ist, doch steht dies im Widerspruch zu

einigen Corridos. Und da der mexikanischen Offizialität ohnehin seit Jahrzehnten

nur widerwillig getraut wird, schenkt man lieber dem Corridista Glauben und das

Mitgefühl dem Banditen. Deren Schandtaten werden unter den Mexikanern - speziell

in den nördlichen Bundesstaaten und ihren Drogenanbaugebieten - ohnehin eher

positiv bewertet. Oft tief religiös, stiften die Bosse Kirchen und organisieren

Feste, investieren in legale Geschäfte und sorgen so für Arbeitsplätze. Die

Schluchten der Sierra werden von ihnen künstlich bewässert - freilich nur, um

die Nachbarn im Norden mit Marihuana zu versorgen. All das wird natürlich von

ihren Chronisten besungen. Wobei der Droge selbst bis vor kurzem wenig Bedeutung

zukam. Doch auch das hat sich in letzter Zeit geändert.

Mit dem Vorwurf,

dass ihre Narcocorridos Menschen zum Drogenkonsum verleiten, leben die

Corridistas seit «Contrabando y Traición». Die Antwort ist manchmal ein

Achselzucken, selten mehr. Zu heuchlerisch scheint ihnen die Drogenpolitik auf

der anderen Seite der Grenze. Mit einer Portion Fatalismus weist man darauf hin,

dass Mexiko den USA zwar Drogen, die Amerikaner ihnen dafür illegal Waffen

bringen. Ein tödliches Gleichgewicht, das durch ihre Lieder kaum gestört wird.

Mit dem es sich gut verdienen lässt und worüber man erzählen kann in einer

Sprache, die nur schwer durchschaubar ist für Aussenstehende. Eine archaische

Codierung, die sich aus den Tiefen des einfachen Volkes entwickelt hat und in

seltsamer Verbindung mit den Neologismen des internationalen Drogengeschäfts

steht, durchzieht die Corridos.

In Culiacán

versteht sie jeder. Die Hauptstadt Sinaloas ist für ihre Liebe zum Verbrechen

berüchtigt. Hier wirkte auch der heilige Malverde, bis er, so die Legende,

hingerichtet wurde. Doch sind die Angaben unsicher. Die mexikanischen Annalen

kennen keinen Jesús Malverde. Was keinen Einfluss auf die Lieder hat. In manchen

Versionen ist er Bauarbeiter, in anderen verlegt er Geleise. Manche sagen, er

wurde von einem Freund betrogen, der ihm die Füsse abschnitt und ihn in die

Stadt schleifte, um die 10 000 Pesos Belohnung einzustreichen. Andere reden vom

Galgen. - Und in einem der Vororte Culiacáns findet man Chalino Sánchez nur

wenige Monate nach seinem legendären Konzert erschossen in einem Strassengraben.

Über seine Mörder spekulieren die Corridistas bis heute.

Andreas Essl

| |

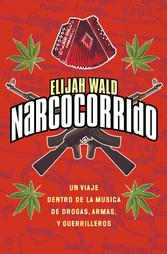

Narcocorrido: A Journey into the

Music of Drugs, Guns, and Guerrillas

by

Elijah Wald

Published in English and Spanish editions by Rayo, an

imprint of Harper Collins

ISBN: 0-06-621024-0

EXCERPT |

|

|

Chapter One

The Father of Camelia

Ángel González

I was hitching

out of Ciudad Cuauhtémoc when the police pulled over. It was 3:00 in the

afternoon, the rain had just stopped, there was no bus, and I had an appointment

in two hours with Ángel González, the father of the narcocorrido.

There were two

policemen, driving in a pickup truck, and they started with the usual questions:

Where was I going, how long had I been in Mexico, could they see my papers. They

kept me a couple of extra minutes, calling my description in to headquarters,

because a Mexican had recently been robbed by a gringo. Then they drove off,

only to return some ten minutes later. I still had not gotten a ride, and was

beginning to worry that I would be late for my appointment, so I was mildly

irritated when they said that they would have to keep me there for a while until

the victim could be brought to look at me. From my occasional experiences with

Mexican police, I expected a long wait.

But no. It was

not five minutes before another pickup pulled up, with two more policemen and a

guy with dirty blond, shoulder-length hair, a limp mustache, and a really

impressive black eye. The truck had barely stopped when the longhaired guy leapt

out, pointing at me and yelling: "That's him! That's the cabrón who

robbed me! He's cut his hair, but that's him!"

In an instant,

I was slammed face-forward against the first pickup, with hands all over me.

Someone was patting me for weapons, two others were pulling my arms down to

handcuff me, while the fourth was shouting, "Keep your hands up!" I was trying

to remain calm, repeating, "I can prove I just got to town. I was in Chihuahua

this morning." No one was listening to me, but the victim seemed to be having

second thoughts. He pulled up my sleeves, looking for track marks, and when he

could not find any he began yelling that no, I was not the guy. By now, though,

the cops were having fun. They had opened my pack and were asking the victim if

the cassettes I had were his. He said no. Then they found my small stash of

dollars — a couple of twenties, a ten, and some ones.

"Is this your

money?" they asked the victim.

"No, mine was

all hundred-dollar bills."

That was

pretty much the end of it. The police removed the handcuffs, murmured an

apology, and drove off, and I caught a ride out toward Basuchil. I did not feel

like asking what business the longhaired guy was in.

In 1972, a new

record swept Mexico. It featured a bunch of unknown teenagers called Los Tigres

del Norte, who sang with the raw, country twang of the western Sierra Madre,

backed by a stripped-down, accordion-powered polka beat, and it had a lyric

unlike anything else on the radio. Called "Contrabando y Traición" (Smuggling

and Betrayal), it told the story of a pair of lovers on a business trip:

Salieron de

San Ysidro, procedentes de Tijuana,

Traían las llantas del carro repletas de hierba mala,

Eran Emilio Varela y Camelia la tejana.

(They left

San Ysidro [a California border town], coming from Tijuana,

They had their car tires stuffed full of "bad grass" [marijuana],

They were Emilio Varela and Camelia the Texan.)

The couple

make it safely across the border, are briefly stopped and questioned by

immigration authorities in San Clemente, but pass without any problem and drive

on to Los Angeles. Arriving in Hollywood, they meet their connection in a dim

alleyway, change the tires, and get their money. Then Emilio gives Camelia her

share and announces that with this money she can make a new start, but as for

him, he is going up to San Francisco with "la dueña de mi vida," the woman who

owns his life. Camelia, who has already been described as "a female with plenty

of heart," does not take this farewell with good grace:

Sonaron siete

balazos, Camelia a Emilio mataba,

La policía solo halló una pistola tirada,

Del dinero y de Camelia nunca más se supo nada.

(Seven shots

rang out, Camelia killed Emilio,

The police only found the discarded pistol,

Of the money and Camelia nothing more was ever known.)

"Contrabando y

Traición" was not the first corrido about the crossborder drug traffic.

There had been ballads of border smuggling since the late nineteenth century,

when import duties made it profitable to carry loads of undeclared textiles

south to Mexico and a Mexican government monopoly tempted freelancers to sell

homemade candle wax to North Americans without going through official channels.

The smuggling business really took off, though, with the imposition of the

Eighteenth Amendment, which prohibited the sale of alcoholic beverages in the

United States. Prohibition was a terrific boon to border commerce. Tequileros

swam the Rio Grande pushing rafts full of booze, drove trucks across desert

crossing points, or used boats to cruise up the coast.

When

Prohibition ended in 1933, the tequileros turned to other products. (They were

not alone; the Prohibition-era gangster Lucky Luciano also went on to smuggle

Mexican heroin.) One year later, on October 13, 1934, what seems to be the first

narcocorrido was recorded in San Antonio, Texas. Written by Juan Gaytan, of the

duo Gaytan y Cantú, it was called "El Contrabandista" and told of a smuggler who

has fallen into the clutches of the Texas lawmen after switching over from

liquor to other illegal inebriants:

Comencí a

vender champán, tequila y vino habanero,

Pero este yo no sabía lo que sufre un prisionero.

Muy Pronto compré automóvil, propiedad con residencia,

Sin saber que en poco tiempo iba a ir a la penitencia.

Por vender la cocaína, la morfina y mariguana,

Me llevaron prisionero a las dos de la mañana.

(I began

selling champagne, tequila, and Havana wine,

But...

(Continues...)