8-6-2003

EMMA'S WAR,

by Deborah

Scroggins

JANUARY 2003

Out of her depth

Emma's War

by Deborah Scroggins. New York: Pantheon Books, 2002, 389 pp.

Reviewed by Sondra Hale

|

EMMA'S WAR

IS TOLD as an exciting adventure story, drawing readers into the intricacies

of the little understood "tragedy of Sudan." The tragedy refers to the

longest-running civil war in Africa, begun in 1983, although one could date

it to 1955, when southern contingents of the army mutinied and slaughtered

northerners. This war has brought famine, displacement and slavery to the

Sudanese people, and I am grateful to Deborah Scroggins for exposing its

atrocities to a larger audience. Yet her book is problematic in other

respects, not the least of which is the focus on Emma McCune, a young

British aid worker turned spouse to one of southern Sudan's charismatic

military commanders, Riek Machar.

For the better part of Emma's War, Scroggins skillfully interweaves

her own experience in Sudan, where she covered the war for the Atlanta

Journal Constitution, with Emma McCune's story. Her writing about the

war is amazing in its depth, revealing what a skilled journalist can do. But

as the book progresses, the thread gets lost and even the chronology seems

garbled. In her ending chapters and epilogue, Scroggins stuffs into a few

pages too many sage comments about Africa, world politics and the meaning of

Emma McCune's life. |

|

|

|

Sometimes Emma's War reads like a standard biography with a chronological

narrative. At other points, it's more like a war story, and McCune serves simply

as a window to the conflict. Then again, it's a critical work of investigative

journalism, with Scroggins on the case of "humanitarian" aid abuses, exposing

the characters who work the aid circuit. In her prologue, she frames McCune and

other aid workers as romantics: "Aid makes itself out to be a practical

enterprise, but in Africa at least it's romantics who do most of the

work--incongruously, because Africa outside of books and movies is hard and

unromantic. In Africa the metaphor is always the belly."

This

is a complex book, raising many questions that can only be touched on in a

single review. So much film and literature on Africa makes a white person the

center of the story-Donal Woods instead of Steve Biko (Cry Freedom), or

Ruth First instead of Nelson Mandela and any number of other South African

heroes (A World Apart). Emma's War joins a long line of literary

depictions of Euroamericans playing out their fantasies, sometimes heroically,

against a colonial backdrop--from Joseph Conrad and E. M. Forster novels to Paul

Bowles' The Sheltering Sky to Michael Ondaatje's The English Patient

to Olivia Manning's The Levant Trilogy. As Scroggins notes, "Africa's

most memorable empire-builders tended to be those romantics and eccentrics whose

openness to the irrational--to the emotions, to mysticism, to ecstasy--made them

misfits in their own societies."

During my own time in Sudan (six years' residence, spanning several decades), I

too lived the colonial life as a white woman, not quite understanding until much

later the power of my whiteness. Emma McCune didn't live long enough to begin to

understand this power and what it meant in terms of race, class and gender, and

Scroggins only tangentially helps readers interpret McCune's life in this way: "She

had a vision of overcoming racism through romantic love. She wanted to break the

seal of her whiteness--to 'make herself that bridge between black and white,'"

in her friend Bernadette Kumar's words.

McCUNE'S STORY runs as follows: she was born in India in 1964 to parents who

were remnant figures of the British Empire. A woman of modest means and mediocre

academic talents, she first went to Sudan in 1987 when she was 23 to teach for

the British organization Voluntary Services Overseas, returning in 1989 to work

for UNICEF-funded Street Kids International (SKI). "In my heart, I'm Sudanese,"

Scroggins quotes her as saying. McCune spent much of the late 1980s in the south

in the midst of war and famine, emerging as a high-profile khawagiyya (foreigner)

and the wife of Riek Machar, whom she married in 1991. Riek Machar was one of

two leading southern guerrilla commanders (although Scroggins insists on calling

him a "warlord"), the other being John Garang, leader of the Sudan People's

Liberation Movement (SPLM). McCune died in a car accident in Nairobi in 1993, at

the age of 29. Along the way with SKI, she opened more than a hundred schools in

southern Sudan while also campaigning against the recruitment of child soldiers.

Such

an outline, however, reveals very little about the idealism, adventure and risk

with which she conducted her life. Nor does it explain why Scroggins chose her

as the protagonist of a 350-plus-page book. She writes that McCune's story may "shed

some light on the entire humanitarian experiment in Africa. Or at least on the

experiences of people like me, people who went there dreaming they might help

and came back numb with disillusionment, yet forever marked." But her

identification with McCune is a troubled one, filled with self-doubt about the

whole enterprise of aid, reportage and just being there. The consequence is a

harshness that can be both unfair and suspect. Scroggins seems to be critical of

those who disapproved of McCune's marriage to Machar; nonetheless, she writes of

McCune: "She had always been attracted to African men, though she can hardly

have laid eyes on many Africans in Yorkshire. Her attraction was frankly erotic.

She found black men more beautiful than white men, even joking with her

girlfriends that the penises of white men reminded her of 'great slugs.'"

A

friend of McCune's is quoted as saying, "[S]he would come out of these swamps of

hell, walk into my wardrobe in Nairobi, and come out looking like something out

of Vogue…." Scroggins hides behind quotes from such "friends" and

colleagues that give the impression that McCune was promiscuous, had a

particular penchant for Nilotics (a generalized ethnic term that includes the

Nuer, the group to which Riek Machar belonged), and was a beautiful but

superficial woman who imagined herself an African queen when she was no more

than a "warlord's consort." That Scroggins may have the last word on McCune

highlights why writing biography can be so vexed, especially if the writer fears

her subject because of the horrors reflected in the mirror.

TWO

ISSUES ARE CENTRAL to Emma's War, and Scroggins' handling of them shows

both the strengths and weaknesses of this book. The first is McCune's role in

the Sudanese civil war itself, one of the bloodiest in this and the last century.

The war is stereotypically referred to in the Western media and by many scholars

as a religious and racial struggle between an Arabized Muslim north and a

Christianized African south. Oh, that it could be so simple! Scroggins, much to

her credit, uses the "layered map" metaphor of Sudanese British writer Jamal

Mahjoub to convey the complexity:

I

have often thought that you need a similar kind of layered map to understand

Sudan's civil war. A surface map of political conflict, for example--the

northern government versus the southern rebels; and under that a layer of

religious conflict--Muslim versus Christian and pagan; and under that a map of

all the sectarian divisions within those categories; and under that a layer of

ethnic divisions--Arab and Arabized versus Nilotic and Equatorian--all of them

containing a multitude of clan and tribal subdivisions; and under that a layer

of linguistic conflicts; and under that a layer of economic divisions--the more

developed north with fewer natural resources versus the poorer south with its

rich mineral and fossil fuel deposits; and under that a layer of colonial

divisions; and under that a layer of racial divisions related to slavery…a

violent ecosystem…. (pp. 79-80)

What

Scroggins omits is a layered map of colonialisms, wave after wave, that have

left the country divided and unable to build a nation. She also omits to gender

the war, highlighting the horrible victimization of women and children, as well

as the greater role of women in holding together the fabric of society. Still,

she teases out many of the complications of oil, political Islam, and myriad

militias and parties. To her, no one is a hero; no side is without blame:

The

Khartoum elite supplied southern and western tribes hostile to the Dinka with

machine guns and encouraged them to form militias to raid the Dinka for cattle

and, some whispered, even for women and children…. There was an Arabic saying

that summed up the strategy of the northern elite: "Use a slave to catch a

slave." The south and its borderlands were divided among many tribes, many

militias…. The region was also home to smaller, weaker peoples who had no

weapons at all…. They were everyone's victims. For the Sudan People's Liberation

Army [the military wing of the SPLM] did its share of raiding, too… It was an

ugly business of robbery and revenge…. (pp. 83-84)

Scroggins ably describes the ethnic, regional and personal splits among SPLM

members, perhaps best dramatized by the insurrection led by the Nuer Riek Machar

against the Dinka SPLM head John Garang. This brought about a temporary

coalition between Machar and his group and the northern National Islamic Front,

until the two guerrilla leaders were reunited in 2002.

Yet

part of the dramatic tension in this journalistic account comes from the

question of how important Emma McCune was to the war and its political intrigues.

Scroggins tends to be dismissive of her. She accuses McCune of holding "a

peculiarly Western idealism that was all the more poignant for being totally out

of place in the context of an African civil war. It was not a political vision

that truly animated Emma as much as an ideal of romantic love. She was in love

with the idea of love and with the idea of sacrificing herself to it." But

others have stressed McCune's role as an advisor to Machar, an identification

that became a double-edged sword for her when Garang's group blamed her for the

insurrection against them. Thus the term "Emma's war"; it was Nilotic custom to

name a conflict after a woman who caused it, although it is surprising that

Scroggins feeds off such sexism.

The

second issue involves Scroggins' critique of neocolonialism in the form of the "humanitarian

industry"-that is, aid and the entire culture of helping which inundates many

African countries with countless outsiders, few of whom have expertise in the

area, know the language, or harbor any deep understanding of the groups with

which they work. Their presence is at worst a kind of adventure and at best a

display of vacuous idealism. Scroggins is rightly critical of the Nairobi and

Lokichoggio expatriate communities whose version of roughing it looks like the

Nile Hilton to the local people. Many of these aid workers are women,

underscoring the complicity of Euroamerican women in the whole colonial and

postcolonial venture.

But

Scroggins pays too little attention to the positive contributions of Emma McCune

and to her popularity among the Nuer. Almost patronizingly she implies that the

Nuer were unable to judge McCune's character for themselves and worshipped her

blindly: she quotes one colleague as saying, "Everywhere we went…the Sudanese

[the Nuer] seemed happy to see Emma even though she had learnt little of their

language. She enjoyed the sort of star attention usually afforded to royalty and

celebrities. In villages, people would run up to her car as she drove past,

bringing presents and seeking advice." She also tends to accept the snide

remarks of other expatriates who might have been envious or felt territorial.

"Everything

about Emma had a story," remarked one of her friends. Another commented that

McCune "was always on trial with the Sudanese because she was a white woman, and

with the expats because she had married Riek...." It seems she was on trial with

her friends, too. The gossip of close-knit communities living under a microscope

is something that Scroggins could have explored rather than taking so often at

face value. Evidently she even left out some of her own interviews that

presented McCune in a positive light (as I learned from a personal communication

with a southern Sudanese colleague). That so many judgments of Emma McCune were

not interrogated for their racism and sexism is troubling, marring a well-told

tale about a war that few readers know enough about.

That

a young white woman in her twenties can offer readers entry into one of the most

complicated and heterogeneous societies in the world suggests that her life is

fascinating precisely because of the intersection of gender, race, sexuality and

politics it represents. Yet for those of us immersed in Sudan and self-critical

of our own presence there, a metaphor Scroggins invokes-that of a cobra spitting

into a mirror--is apt. Scroggins says this metaphor reminded her "of how the

West is alternately enthralled and enraged by its own reflection in Africa." And

it reminded me of why analyzing the spaces some women have invented for

themselves in military and political struggles matters.

October 20, 2002, Sunday

BOOK REVIEW DESK

The Tall Woman From Small

Britain

By George Packer

EMMA'S WAR

By Deborah Scroggins.

Illustrated. 389 pp. New York:

Pantheon Books. $25.

|

While Americans have been

thinking about other things, a civil war in Sudan that began in 1983 has

killed more than two million people. The conflict between the Arab Islamic

north and black animist south is so obscure, so complex, so chronic and so

devastating that it stands as the emblem of African apocalypse coexisting

with Western indifference. The deaths of 10,000 southern Sudanese by

slaughter or 100,000 by starvation can occur with hardly a mention in

American newspapers.

Deborah Scroggins, who

used to cover the war and its famines for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution,

is something of an expert on the difficulty of getting readers to pay

attention, and she can be forgiven for building her own account of the

Sudanese civil war around the short, happy life of an Englishwoman who

became involved in it. |

|

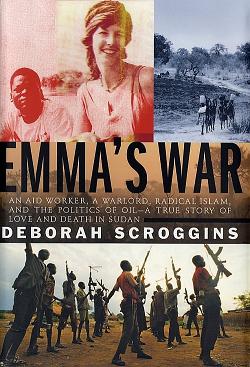

Emma McCune and her husband Riek Machar

with their bodyguards.

|

|

Scroggins half-apologizes for

this choice in her author's note, but there is probably no other way to get more

than a handful of Westerners to read a book about Africa's longest-running war.

As Hollywood knows, we need a character to identify with, and it helps if she's

young, beautiful and recklessly passionate. In the case of ''Emma's War,''

though, the decision to put an attractive white face on an ugly African war

doesn't seem meretricious. In telling Emma McCune's story, Scroggins brings

Sudan's agony to vivid life; at the same time, she gives us a lyrical,

suspenseful, psychologically acute study in idealism and self-delusion.

Emma McCune was the daughter

of fallen English gentry, raised in Yorkshire on a mean income and fantasies of

colonial glory. In the early 1980's, when she went off to Oxford Polytechnic and

fell in with a group of friends who were obsessed with Africa, she began to live

out her birthright without the actual empire: ''They wanted lives with an edge.

Although many of them came from colonial or diplomatic backgrounds, they all

abhorred the British Empire and blamed colonialism for most of Africa's problems.

They felt their romance with Africa somehow set them apart from the restraint

and tedium of middle-class English life.''

In the 80's, Africa's famines

and the response by rock stars like Bob Geldof of Band Aid infused a generation

of Europeans and Americans with this romance. They listened to African music,

wore African clothes, fell in love with actual Africans and came to hate the

narrow comforts of their lives at home. In 1987 Emma found her way to the hot,

starving, fly-ridden country everyone agreed was the worst place of all, and yet

one of the most seductive. She fell into a job doing the only thing for which an

idealistic, adventurous, unskilled young white person in Sudan is qualified. She

became an aid worker.

Among its virtues, ''Emma's

War'' presents a brilliant portrait of this misunderstood type. Aid workers in

Africa play a role not unlike that of the explorers and missionaries who paved

the way for colonialism -- like Charles George Gordon, sent by Queen Victoria to

end the slave trade in Sudan, only to find moral clarity ever more elusive,

before meeting his fate at the hands of Islamic fundamentalists in Khartoum. ''It's

a story that began in the 19th century much as it seems to be ending in the

21st,'' Scroggins writes, ''with a handful of humanitarians drawn by urges often

half hidden even from themselves.''

As their 19th-century

predecessors carried the flag of Christian optimism, aid workers today bear the

burden of human rights idealism for a less confident, more jaded West. While the

rich world withdraws from Africa and its endless disasters, the aid workers stay

behind to assuage our collective conscience. When war turns whole populations

into starving refugees, the power of life and death falls to young white people,

and yet their presence usually plays into the hands of one or another armed

faction and only sustains the suffering it's supposed to end. Food, guns,

desperation, fantasies of goodness: Scroggins calls it ''the intersection of the

politics of the belly and the politics of the mirror,'' and the vast

inequalities of power leave no one's hands clean. No wonder aid workers suffer

from extremes of grandiosity and despair. We imagine them as saints, Scroggins

argues, but we have no stomach for the ambiguities and failures of the long haul.

Emma resolved the dilemmas of

aid work by ignoring them. Funny, daring, physically brave to the point of

foolishness, she wore miniskirts, kept duty-free vodka and copies of Vogue in

her tent and had a string of affairs with Sudanese men (white men's penises

reminded Emma of ''great slugs''). She also helped set up schools for thousands

of southern Sudanese children. Local people called her ''the tall woman from

small Britain.'' Scroggins, close to Emma's age and traveling in the same

expatriate circles, saw her on only a few occasions, so the book has the quality

of a search for an elusive and increasingly legendary woman. She portrays Emma

with something like Nick Carraway's disapproval and envy and admiration of that

other doomed romantic figure, Gatsby.

The story takes an ominous

turn when Emma falls in love with a commander of the rebel Sudanese People's

Liberation Army named Riek Machar. A likable seducer, he enjoyed a reputation as

''the Bill Clinton of Sudan.'' Their affair makes the other aid workers question

Emma's neutrality, and the suspicions only deepen when Emma and Riek (whose

Sudanese wife and three children are marooned in England) marry in the bush in

the midst of another disastrous refugee exodus. Soon afterward, Riek tries

unsuccessfully to overthrow John Garang, the leader of the rebel movement, and

the revolt of the black south against the Arab north -- ostensibly fought in the

name of a ''secular, democratic Sudan'' -- disintegrates into mass killing among

southerners along tribal lines.

Garang's forces accuse Riek's

new English wife of being a spy and a whore, and they call the tribal fighting

''Emma's war.'' Fired from her humanitarian job, abandoned by most of her

expatriate friends, Emma becomes Riek's unapologetic spokeswoman. She refuses to

see that she has joined sides with murderers. In this, too, Emma reflects the

long tradition of white vanity and illusions about Africa: She ''was not by

nature introspective. By temperament she was a campaigner, a fighter, a natural

partisan. And to this tendency to pick sides, she added a peculiarly Western

idealism that was all the more poignant for being totally out of place in the

context of an African civil war. It was not a political vision that truly

animated Emma as much as an ideal of romantic love.''

Even as they shun Emma, the

more thoughtful aid workers understand that all of them are compromised -- that

''everybody who is there is part of that war.'' In her blithe, willfully blind

way, Emma takes this unhappy truth to its logical extreme. She becomes something

of a white queen among Riek's Nuer people. Before long, she and Riek are dining

on fish that Riek's soldiers have confiscated from a defenseless and starving

tribe called the Uduk, who have been driven all over southern Sudan and

exploited by every faction in the war. At this point, the narrator's moral tone

begins to sound less like Nick Carraway than like Conrad's Marlow in pursuit of

Kurtz.

Toward the end, ''Emma's War''

loses a bit of its narrative power. This is almost inevitable, because of the

way Emma's life ends (in an automobile accident) and the way Sudan's war doesn't.

Radical Islamists in the north, hungry to exploit the south's oil reserves, form

a distinctly unholy alliance with Osama bin Laden, a Canadian oil company and

Riek himself, who turns up in the pocket of his erstwhile Arab enemies. Earlier

this year, Riek, ever the survivor, switched sides again and rejoined forces

with Garang. The need to sell oil and the war on terrorism have forced the

Islamists in Khartoum to attempt an opening to the West. There are, as always,

rumors of a peace accord. Almost 20 years after it began, Sudan's civil war

rages on. And Deborah Scroggins, now an ex-reporter and a disillusioned

humanitarian, still has no answer for the old Sudanese man who asked her in

1989, ''Why are you people in Britannia and Europe hearing this and not helping

us?''

In the end, the heroine of

''Emma's War'' was irrelevant to Sudan. ''She was really nothing,'' says a

prominent Sudanese. ''She was just an adventurer. If she were in a European

setting, she would never even have been noticed.'' But Emma's dreams, delusions

and failures are those of all the white people who have tried to bring their

idea of the good to Sudan. This is what makes her story, told so well here,

worth telling.

George Packer is the

author of ''The Village of Waiting'' and ''Blood of the Liberals.''

Published: 10 - 20 - 2002 ,

Late Edition - Final , Section 7 , Column 1 , Page 12

Innocence abroad

Kevin Rushby on Deborah

Scroggins's biography of a well-intentioned young woman caught up in a brutal

African conflict, Emma's War

Saturday March 8, 2003

The Guardian

Emma's War

by Deborah Scroggins

220pp, HarperCollins, £17.99

|

In Graham

Greene's The Quiet American , Pyle is the earnest young American who

blunders into an alien culture believing a well-meaning heart is enough to

sort out the problems. Instead, his straightforward innocence and romantic

simplicity are the very things that pull him into a moral quagmire, causing

far more damage than ever a cynical old-timer might have.

Imagine a

similar character in a country with several hundred more tribal groupings

than Vietnam, a similarly huge number of languages, a sordid history of one

half enslaving the other, plus a civil war between north and south that has

cost two million lives since 1956 and caused incalculable misery to boot.

Africa's largest country, Sudan, can look very bad on paper. |

|

Emma

sitting on her bed at Ketbek |

|

Deborah

Scroggins, an American journalist, certainly sets a vile enough scene for her

account of one, rather unusual, Englishwoman's involvement with Africa's

longest-running civil war. "I could only find one person who had ever travelled

to Sudan for pleasure," she writes, and nothing here would encourage you to

become the second. In her eyes the north is a desiccated hell inhabited by

Muslim fanatics, slavers and bigots; the south is capable of natural beauty, but

the people are either famished and dying or well-fed and untrustworthy.

Into this, in

1989, arrived Emma McCune, a young Englishwoman with a heartfelt concern for the

suffering children of the south and a simple love of black men. Bewitchingly

handsome and possessed of great energy and verve, though few qualifications,

Emma shimmied her way into a job setting up schools in the rebel-held parts of

the south. There she began to show some unexpected qualities: she got things

done, she was physically brave, sometimes reckless, and she didn't give a

tinker's cuss about the restrictions the UN aid-ocrats tried to put on her.

In the south

she got to know Riek Machar, zonal commander in the rebel Sudanese People's

Liberation Army. Love blossomed and, very soon after, her reputation among aid

colleagues began to wither and die. Was this old- fashioned suspicion of one who

crosses the invisible line and "goes native", or had her simple romantic

qualities, like those of Pyle, been perverted by the prevailing madness?

Certainly Emma was drawn into a web of political intrigue when Riek broke with

the SPLA and started a war within a war. Her use of UN radio channels to call in

food flights was said to have led the northern Islamic government not only to

bomb the sites she mentioned, but also to accuse the UN of taking the southern

rebels' side.

This tale is

interwoven with Scroggins's trips to Sudan and a thoroughly researched account

of the country's history. That she appears to make sense of all the military

campaigns and forced migrations is a testament to her tenacity, but somehow, no

matter how high the pile of facts grows, the truth proves elusive. What does

emerge is Scroggins's own agenda. When she gets out of Khartoum, pumped up by

ridiculous "darkest Africa" rhetoric, her experiences are never far from the

machine guns or feeding stations.

She

illustrates the northern oppression of the south by suggesting that after

independence only one secondary school was allowed and Arabic was the enforced

medium of instruction. This is false. She quotes, in purplish prose, the

shattered aid worker who wants to do "one clear thing" in all the chaos, and

that is to get a southern child out to safety - Europe, that is. The horrors of

civil war in the south are all too real, but this account leaves out anything

that is good in Sudan and panders to those elements with an anti-Islamic agenda.

Nevertheless,

on the subject of famine relief she does land some telling punches, particularly

the role of aid agencies and oil companies in the conflict. Ignorance and

prejudice emerge at all times. No outsider bothers to learn the tribal languages

or read the anthropology of an older, more dedicated generation. Sometimes the

sheer horror of it all reminds us of that other literary example of extreme

western methods of involvement: Conrad's Mister Kurtz. In one scene, a young aid

worker water-skis past crowds of starving refugees, using up precious fuel,

while the head of a UN mission wrangles with Riek over his hungry soldiers

eating UN rations. Meanwhile, in Somalia, the UN spends $300m on a luxury base

in Mogadishu for US troops in Operation Restore Hope - one-third of Somalia's

national budget before the war.

All these

interventions, so costly in lives and money, make Emma's contribution seem no

less naive but far more genuine. She had, after all, more human warmth than any

inhabitant of Greene-land. Emma and her unborn child died in a car crash in

Nairobi in 1993 but her life deserves remembering, for, like this book, it was

flawed but important.

Kevin Rushby's

latest book is Children of Kali .

"Emma's War" by Deborah Scroggins

When a beautiful, idealistic Western aid worker

fell in love with a Sudanese warlord, a terrible tragedy of hunger and violence

was set in motion.

By Michelle

Goldberg

|

Dec. 11,

2002 | "Emma's

War" is a tale of high romance and tragedy that offers an epic view of the

kind of international issues currently crowding the newspapers. There may be

more encyclopedic books on the ugly machinations of oil politics, the

destruction well-meaning Westerners can wreak when they interfere in

conflicts they cannot grasp, the way failing states incubate terrorism, and

the clash between atavistic tribal politics and democratic ideals. But none

can match the page-turning melodrama of Deborah Scroggins' dazzling

biography of Emma McCune, a gorgeous English aid worker who became the

second wife of a Sudanese warlord and helped tear southern Sudan apart even

as she risked her life to save it.

Though her story is a kind of modern "Heart of

Darkness," Emma, who died at 29 in a car accident, is a character too

grandiose for most novelists to pull off -- a beautiful, brave, foolish

woman who throws herself into a vicious war, crossing the line separating

charitable Westerners from the objects of their charity. She's a person at

once boundlessly generous and dangerously self-absorbed.

Scroggins describes Emma in London after her

marriage: "She made a dramatic entrance at one party wearing a dress by the

designer Ghost that must have cost several hundred pounds. 'Who is that

stunning woman in black?' the guests were asking. |

|

|

|

She

relished answering that she was the wife of an African guerrilla chief." Emma

was entrenched in the agony of Sudan as no other Westerner was, but almost until

the end of her life, one senses it remained a romantic adventure to her. She

shows both intense caring and adrenaline-junkie callousness, a duality that

seems to affect many Western forays into war zones.

The

book comes at a time when many of the issues it raises are being fiercely

debated. Our administration seems full of sunny certainty that it will bring

democracy to Iraq, a country riven by sectarian hatreds. That view is abetted by

exiles who tell our leaders precisely what they want to hear. Thus, Emma's

husband, Riek Machar, serves as a cautionary example.

As

Scroggins writes, local people called Riek "the Bill Clinton of Sudan." He's

charismatic, Western-educated and conversant in the rhetoric of human rights and

democracy. Initially, he fights the Muslim fundamentalist government in the

North, which is supported by Osama bin Laden and his ilk, and which is

determined -- with the help of foreign energy companies -- to exploit the oil

reserves in the South. Yet, while Emma is determined to see Riek as a

Western-style hero, he eventually starts a vicious tribal war within the South,

manipulating starving refugees to garner international aid that benefits his

struggle.

Meanwhile, the moral complexities of the aid industry itself have been thrown

into high relief by David Rieff's recent "A Bed for the Night: Humanitarianism

in Crisis." In that book, Rieff shows how relief workers can augment crises --

for example, by working in refugee camps that double as sanctuaries for militias.

Writing about aid workers, Rieff asked, "Are they serving as logicians or medics

for some warlord's war effort (as they probably are in the Sudan)? Are they

creating a culture of dependency among their beneficiaries? And are they being

used politically by virtue of the way government donors and U.N. agencies give

them funds and direct them toward certain places while making it difficult for

them to go to others?"

"Emma's

War" doesn't offer a single answer to such questions, but it illuminates them

and renders them immediate, showing the way war can twist an outsider's blazing

idealism into something sinister.

Emma

begins as an intrepid, passionate girl in love with Africa. She moves there in

1989, when she's 25. The most daring in a circle of young expats who pride

themselves on their fearlessness, she lands a job with Street Kids International,

a charity devoted to starting schools in war- and famine-ravaged Southern Sudan.

It's important work. The Christian and pagan Sudanese are desperate for

education, realizing it's one of the main advantages the Arabized North has over

them. Thus, many parents were sending their children to Ethiopian refugee camps,

hoping they'd go to school while being trained as rebel soldiers. For Emma,

local schools were a way to keep children out of war.

When

she realizes that her Land Cruiser can't reach many of the villages she wants to

help, she sets off through the bush on foot. "Emma's willingness to get out and

walk from village to village won her respect from the southern Sudanese,"

Scroggins writes. "They called Emma 'the Tall Woman from Small Britain.' She was

such a novelty that they drew pictures of her in her miniskirt on the walls of

their wattle-and-daub tukuls."

It's

through her work with Street Kids International that Emma meets rebel commander

Riek Machar. The southern rebel army SPLA had blocked her efforts to expand her

schools into Riek's district because, she believed, they'd interfere with the

rebels' campaign to recruit child soldiers. With characteristic audacity, she

decides to confront Riek herself, traveling to a relief conference he was

attending in Nairobi, Kenya.

Charmed, he agrees to her request with startling rapidity. "Emma was bowled

over," Scroggins writes. "This tall man with the soft voice shared her dreams

for the children of southern Sudan ... He trusted her so much that he was going

to investigate her reports that the boys were being trained for the rebel army!"

According to Emma's mother, they slept together that night.

Emma

moves Street Kids International's office to Nasir, Riek's headquarters. Here

what was formerly an affectionate portrait of Emma begins to turn ugly. Nasir

was being besieged by hungry refugees. Scroggins writes, "Thousands of refugees

squatted along the muddy banks of the river, waiting for food. The dead bodies

and the raw sewage from the refugees had contaminated the Sobat [river]. After

drinking from it, people started coming down with a deadly variety of diarrhea.

Torrents of rain poured over them as they lay in their own excrement ... In the

midst of this chaos, Emma floated around in long skirts and Wellington boots,

looking mysteriously happy."

At

the same time, Emma's doctor friend, Bernadette Kumar, perhaps the one real hero

in the book, is working furiously to keep up with the mounting calamities when

Emma calls her away. Believing she must be sick, Bernadette hurries over, and is

stunned when Emma gushes, "I'm in love, and I've made up my mind. I'm going to

get married -- here in Nasir! And I want you to be my bridesmaid."

This

moment comes more than halfway through the book, but it serves to bifurcate it,

marking the moment at which Emma plunges into a moral limbo. Her solipsism seems

almost demented, and it gets worse as the crisis progresses. After all, Riek's

men weren't exactly on the same side as the aid workers. They stole much of the

food for themselves, and kept a group of children, the so-called Lost Boys,

half-starved in order to use them to extract more supplies from the foreigners.

Scroggins sums up the same kind of ethical swamp that Rieff wrote about: "When

you see starving Rwandans or Somalis or Bosnians staring out of your television

screens with solemn dignity, you get the idea that such places must be like mass

hospitals in the dust. You think they must be entirely populated by emaciated

children lining up for food handed out by heroic aid workers. Television leaves

out the manic excitement of the camps. Power is naked in such places. It comes

down to who has food and who doesn't. The aid workers try to cover it up, to

make the men with guns at least pretend to deny themselves in favor of the

children and the women. The men play along for a while, but then the mask falls

away. The strong always eat first ... and very soon some of the aid workers

began to wonder where Emma stood -- on the side of the refugees or with Riek."

The

answer quickly becomes clear, especially once Riek attempts to overthrow SPLA

leader John Garang. Garang was murderous and tyrannical, and his refusal to

settle for a free South instead of a democratic, united Sudan seemed to auger

war without end. When Riek tries to supplant him, he does so in the name of

values that the aid workers espouse, and they're initially enthusiastic.

But

in order to garner support against Garang, Riek falls back on exactly the kind

of tribal politics he claims to abhor. Garang is a Dinka, while Riek is a Nuer.

The two groups had fought together against the North, but after Riek's split

with Garang, they start slaughtering each other in what comes to be known as "Emma's

War." The battle scenes are horrifying. "Riek used all the symbols of the Nuer

religion and tradition to rally his people to his side," Scroggins writes. "The

Nuer ... wore white ashes on their bodies and the white sheets over their

shoulders that were supposed to protect them from bullets ... They made a

terrifying sight as they marched, chanting war verses about their ferocity. They

drove Garang's men all the way back to their leader's hometown of Bor. Then the

killing really started."

The

scene of the massacre resembles a Bosch painting. An aid worker describes it,

"The whole air stank ... And just everywhere were dead cows, dead people, people

hanging upside down in trees." Observers, Scroggins says, "saw three children

tied together with their heads smashed in. They saw disemboweled women ... They

had to cover their faces to breathe inside the hospital where Bernadette Kumar

had once operated." Emma refuses to admit the reality of the massacre to herself,

much less to her friends, further alienating her from Africa's relief workers.

Needing support, Riek makes a covert alliance with the Northern government, the

very opponent he'd valiantly fought against -- and that government, wanting to

divide the rebels and protect the oil fields in Nuer territory, is happy to

supply him with weapons. Taking advantage of the South's internecine fighting,

the North regains much of the territory it lost to the SPLA. Oil concessions are

sold. The fighting continues today.

Ultimately,

Emma resembles a Graham Greene character even more than a Joseph Conrad one --

she's like Alden Pyle in "The Quiet American," sure she can save a country she

doesn't quite understand with her own love and righteousness. Indeed, the love

between her and Riek seems genuine, which is why it's heartbreaking that the

same love was so corrupting. In the end, like Greene's fictions, Emma's life

leaves one with the sense that naiveté can be

far more deadly than cynicism.

About the writer

Michelle Goldberg is a staff writer for Salon based in New York.

A good woman in Africa

Emma's War, by Deborah Scroggins, follows a

Westerner who travelled to the Sudan, married a warlord - and changed nothing,

says Geraldine Bedell

Sunday March 9, 2003

The Observer

Emma's War

by Deborah Scroggins

HarperCollins £17.99, pp220

Emma McCune was a beautiful young Englishwoman who

conceived a romantic passion for Africa, went to the Sudan to be an aid worker

and ended up marrying a warlord. Her story is extraordinary, but also quite thin.

Emma didn't change anything. She become embroiled in the politics of southern

Sudan, but made no difference, averting her eyes from things she didn't want to

see. She was infuriating, in the way that headstrong, very attractive young

women can be.

Deborah Scroggins would be the

first to acknowledge that Emma was less significant than she liked to think. (She

was given to signing herself First Lady-in-waiting, a reference to her

expectation of becoming the wife of the President of a seceded southern Sudan).

Scroggins, an American journalist, was responsible in her early career for

alerting the world to the Sudanese famine of 1988, in which 250,000 people died,

and which, as she notes bleakly, not many people remember any more.

She has an impressive grasp of

the brutal complexities of politics in the Horn of Africa, and what she has done

in this book, very cleverly, is to weave the short story of Emma's life into the

vast, horrific story of the Sudan. Her book is a timely reminder that the

history of this distant and untamed place has dire repercussions for us all:

Osama bin Laden was in the country at the same time as Emma, supporting the

Islamic government whose rule Emma's husband was resisting.

If Scroggins has a theme, it

is that the desire to do good in Africa has repeatedly tripped up Europeans and,

latterly, Americans. Emma McCune went out to the Sudan as a missionary for the

Western gospel of human rights, rather as General Gordon went to abolish slavery.

The slavery continued after Gordon's death, and civil war and starvation

continued after Emma's. Modern aid workers find it necessary, as Gordon did, to

do business with the warlords and find themselves sucked into the maw of civil

war, implicated in atrocities.

Africa consumes them, just as

it consumed the US marines who tried to intervene in neighbouring Somalia in

1993, when bin Laden-trained guerrillas killed 18 Americans (in the incident

that became the subject of Ridley Scott's Black Hawk Down). The marines pulled

out after that; Scroggins notes quietly that 'we like our heroism on the cheap'.

Emma McCune was born in India

in 1964, the child of colonial parents born after the closing days of Empire.

Her father lost his job to a local man, and the family moved to Yorkshire and a

life to which he, at least, was singularly unsuited. He started an affair,

embezzled funds from the local Conservative Association and, ultimately,

committed suicide. The McCunes moved from a Queen Anne hall to a council house

and dreamt of how happy they had been far away from England.

It was at Oxford, where Emma

was studying art and history at the polytechnic, that she first met young,

idealistic Sudanese students and refugee officials. She slept with a bewildering

array of them, both in Britain and in Africa, and started hanging around with

academics and aid workers who were experts in the region. Eventually, she found

her way out to Sudan and a job with Street Kids International, setting up

schools.

Scroggins, on the one occasion

the two women met, remembers being shocked by the fact that, unlike the other

aid workers and journalists, who wore modest T-shirts and khaki shorts in an

attempt to make themselves less visible and sexy, Emma splashed about in a

bright miniskirt. But in other respects, she was typical: most of the work in

Africa is done by romantics, by aid workers hired, in Scroggins's view, less for

their knowledge of the continent than their familiarity with Western notions of

what it needed - concepts such as women's rights and 'grassroots development'.

Their motives, like anyone's, were muddled: 'In truth, the average aid worker or

journalist lived for the buzz, the intensity of life in the war zone, the

heightened sensations brought on by the nearness of death and the determination

to do good.'

Emma probably never really

understood the crisscrossing currents of Sudanese politics. There was the

northern government versus the southern rebels, the Muslims versus the

Christians and pagans, the 100 ethnic groups with their clan and tribal

subdivisions, the linguistic conflicts, the colonial and racial differences (Arabs

versus the rest). And there was oil in the South, which the northern government

wanted to get its hands on, and Sharia law, which the North was under pressure

from its backers (including bin Laden) to impose on the entire country.

Riek Machar, the man Emma

married, was a deputy commander of the southern rebels, the Sudan People's

Liberation Army. He had a PhD from Bradford Polytechnic and was already married

to a Nuer woman who lived in England with their three children. But the

attraction to Emma was immediate, mutual and overwhelming; they began living

together. Within months, they were married.

Emma was a natural partisan,

an instinctive campaigner, with an added Western idealism that Scroggins

considers to have been out of place in Africa. Once married to Riek, she took on

his struggle as her own. After he launched an internal rebellion against the

leader of the SPLA, there were atrocities on both sides: massacres, thefts of

food, and children deliberately kept hungry to pressurise the UN to send more

aid, much of which ended up in the hands of soldiers. Children were frequently

sold (or captured) into effective slavery as trainee soldiers.

Emma's friends in the aid

community could never be sure how much she knew - she always defended Riek and

argued that mistakes were not his - but her closeness to the fighters left them

uncomfortable.

Emma died in a car accident in

Nairobi in 1993. Although she had received death threats, it seems unlikely she

was murdered. She was 29, and five months pregnant. An obituary in the Times

referred to her as an aid worker, though she hadn't been an aid worker for two

years: the error, Scroggins says angrily, was 'another example of the West's

inexcusable narcissism: the lazy refusal to see beyond our salvation fantasies'.

Scroggins has written a

wonderful book, driven at bottom by her own passionate disappointment; she

speaks at one point of 'people like me, people who went there dreaming they

might help, and came back numb with disillusionment'. Emma's War is a gripping

history of the Sudan, which doesn't shirk the country's complexities and which

integrates into its cruel history the saga of Western efforts to help and

interfere.

But she leaves us with an

unresolved dilemma. Are we supposed to watch people go hungry? Give up hope for

the starving? How can we not empathise? We are part of their world. Their

violent deaths and starvation are barely imaginable to us, but we are partly

responsible. The consequences of our interventions are still unspooling. We are

linked to the peoples of the Sudan whether we like it or not, and we have to

pray that their tribal violence does not catch up with us.

TheSacramentoBee

BOOK

REVIEW: Story

of aid worker lends insight to Africa

By

CLAY EVANS, Daily Camera of Boulder, Co.

Published

11:54 a.m.

PST Wednesday, January 22, 2003

(SH) - How

many Americans can point to Sudan on a map? How many are aware that it is the

largest nation in Africa, covering almost 1 million square miles? What people

live there?

If you can't

answer such questions, you are not alone. But if you read Atlanta-based

journalist Deborah Scroggins' deeply researched new book, "Emma's War," you'll

come away with answers - and very likely more questions and a sense of palpable

tragedy.

Sudan

actually has been a blip on the American media radar in the days following the

Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks: Aren't there radical Arabic Muslims in the

country's north raiding, pillaging, murdering and slave-taking among the mostly

African pagan-Christian south? Yes. But that doesn't begin to tell Sudan's

depressing story.

Scroggins

tells us much more, using a fascinating focal point around which to weave a tale

of Western aid and arrogance, Islamic radicalism, deeply entrenched tribal bad

blood, and always in the background, the Western lust for oil.

The Emma of

the book's title, Emma McCune, was a bright, pretty and rebellious British

expatriate who first fell in love with the brutal and lovely Sudan while serving

as an idealistic foreign aid worker. In her heart, she considered herself

Sudanese, but eventually, her marriage to a powerful, charming southern warlord

blinded her to the very kind of atrocities she had once hoped to prevent.

Scroggins,

who was working for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution when she first began

reporting from the Horn of Africa, is an able guide through its late colonial

history, the endless struggles between the Arab north and African south, and all

the while, the machinations and chess-playing by international oil concerns,

from Chevron to the Saudis.

Her time on

the ground, especially in the late 1980s and later, the Clinton era, when

American forces were supposed to be helping a humanitarian mission in

neighboring Somalia (the failure of which caused Osama bin Laden to pronounce

that "Americans are cowards") gives the reader a window seat into a world of

almost ceaseless tragedy and struggle. Bin Laden's al-Qaida found its cradle in

Sudan.

Early on,

Scroggins visited a huge refugee camp outside the capital Khartoum, called

Hillat Shook. Part of her description gives a flavor for the situation at the

time:

"Outside the

hut a woman appeared to be cooking something over a burning tire. Despite the

awful smell and industrial debris, the scene was recognizably African. To my

citified mind, it looked as if an avant-garde artist had been given the task of

creating an African village out of toxic waste materials."

While it's

true that the fundamental conflict in Sudan then and today was between the

Muslim north and pagan/Christian south, Scroggins and fellow journalists

witnessed the brutalities of internecine "brush" warfare between southern tribes,

particularly the Nuer and the Dinka. Whole villages were laid to waste, their

inhabitants mutilated, cattle (the Dinka sign of wealth) stabbed in the eyes and

left to die, children kidnapped and taken to camps to be trained as soldiers.

Amid all

this, Emma McCune, who had begun as a vociferous advocate for children, lost

sight of her idealism when she impulsively married Riek Machar of the Sudan

People's Liberation Army. She angrily justified slaughter by her husband's

soldiers when they were battling another warlord, John Garang (who was supported

by the United States), and tittered charmingly as she dined on fish stolen from

weaker tribes' nets.

Scroggins'

book is enormous and complex, peering down dark alleyways to find few innocents

in Sudan's struggles. Religion, whether Christian or Muslim, becomes

justification for unimaginable horrors (an estimated two million people have

died in the country's 14-year civil war), but always in the background was the

desire to control southern oilfields.

Emma died

with a whimper, killed in a car crash. And even though fighters opposed to Riek

derisively called their battle "Emma's War," she was just a bit player.

Ultimately, Scroggins finds sympathy for her tragic subject: "She had beauty,

passion, a radiant spirit. She wanted to help. Yes, she was up to her neck in

horrors. But the horrors almost certainly would have happened without her."

Emma's War:

An Aid Worker, A Warlord, Radical Islam, and the Politics of Oil - A True Story

of Love and Death in Sudan by Deborah Scroggins. Pantheon, 389 pp. $25

BOOK REVIEW

Twisted politics and starvation

Emma's War, An Aid Worker, a Warlord, Radical

Islam, and the Politics of Oil - A True Story of Love and Death in Sudan.

Deborah Scroggins, Pantheon: 390 pages.

By

Bernadette Murphy

Special to The Times

January 7 2003

"When you see the starving Rwandans or Somalis or Bosnians

staring out of your television screens with solemn dignity, you get the idea

that such places must ... be entirely populated by emaciated children lining up

for food handed out by heroic aid workers," writes journalist Deborah Scroggins

in "Emma's War," a compelling and disturbing book about the troubles plaguing

Sudan (and many other African nations), and the role she believes Western

intervention has played in perpetuating them.

Those images, she tells us, fail to show the "manic excitement" of the camps,

where those with power, whether through money or guns, are the ones who reap the

benefits. "The aid workers try to cover it up ... but then the mask falls away.

The strong always eat first. Then the question for the aid workers is: Are we

doing more harm by feeding the men with the guns than we would by letting

everyone else starve?" This inquiry forms the heart of her book, which shows how

religion, politics and greed influence the starvation, slavery and abject

poverty in Sudan -- "potentially one of the richer pieces of real estate in the

world, with ... crude oil reserves of 262 million barrels."

Scroggins artfully arranges these aspects around two key stories. The primary

tale, set in the late 1980s and early '90s, tells of Emma McCune, a charismatic

and romantic British aid worker. " 'In my heart, I'm Sudanese,' " McCune says of

her fascination with the people and the country. Arranging education for

children, she falls in love with Riek Machar, a leader of the Sudan People's

Liberation Army, or SPLA. Machar is a key player in the civil war that has all

but destroyed the country. (The longest-running civil war in Africa, the

conflict has racked up an estimated 2 million deaths since 1983.) Pitting

factions of the Christian and pagan south (including the SPLA) against the

northern Islamic government (not coincidentally backed by Osama bin Laden, who,

until six years ago, lived there), the war seems to have oil rights at its core.

By becoming the warlord's wife and taking up his fight, McCune blurs the

supposed delineation between the neutral assistance offered by the aid community

and outright support for one faction. In her drive to improve the life of the

people she's come to love, she blinds herself to the harm done by her husband's

activities (she denies the existence of a massacre in which Machar played a

leading role) while she shapes the reality of the situation around her to suit

her idealized self-image. To fellow aid workers, McCune becomes "a symbol of how

a relief organization meant to be neutral had become part of the machinery of

the civil war." To Scroggins, McCune is emblematic of the misplaced goodwill

that constitutes much of the West's humanitarian efforts.

Woven throughout are Scroggins' own experiences covering Sudan for the Atlanta

Journal-Constitution, witnessing cases of child slavery and overwhelming

starvation. This personal narrative balances the account, showing how

heart-wrenchingly difficult situations like Sudan are. After seeing starving

conscripted child-soldiers tended by well-fed warlords, she asks whether, by

considering children innocents and more deserving of food than adults, the U.N.

inadvertently encourages groups like the SPLA to starve children in hopes of

receiving more aid.

We in the West, Scroggins suggests, like to see ourselves as gallant saviors,

bringing redemption to those in need. When our efforts fail to fix the problems,

though, we're just as happy to change the television station.

Scroggins detects some of the roots of the rage that fueled the Al Qaeda

terrorist attacks as she considers the U.S. intervention in Somalia and other

countries on the Horn of Africa a decade ago. On Sept. 11, she writes, "Osama

bin Laden's followers smashed the smug conviction that it is up to us to choose

whether to tend to the world's festering sores or to turn our backs on them."

Western intervention, "carelessly entered and even more carelessly exited," she

argues, has "borne evil fruit."

As we read headlines of threatened war in Iraq, this book, with its incisive

examination of the West's intervention in Third World counties and its

resonating effects on the web of humankind, should be required reading.

09 March

2003

Books:

More than a woman

Emma's war: Love,

betrayal and death in the Sudan by Deborah Scroggins (Harpercollins, £17.99)

Reviewed by Lesley McDowell

THIS remarkable book by

American journalist Deborah Scroggins is a rare beast -- the life story of an

individual and the history of a nation that conveys the intimacy of the former

and the scope of the latter. A moving, enlightening, entrancing account of

British woman Emma McCune -- who attained brief notoriety in the early 1990s for

her marriage to a Sudanese warlord, Riek Machar, before she died, at the age of

29, in a car accident -- Scroggins's work promises a great deal and delivers on

every count.

Emma McCune was born in

India in 1964, in the fast-fading shadows of the British Empire. Her parents had

met there while her father Julian (or 'Bunny') was working as an engineer and

the colonial structure was still in place, granting ex-pats comfortable

bungalows, Indian servants and nannies . By the time Emma was born, much of this

free and easy lifestyle had been dismantled, and Bunny McCune was sent back to

England, where he settled in Yorkshire, home of his family, took to drink and

womanising and finally killed himself.

Scroggins makes clear

the link between Emma McCune's fascination with Africa, another great colonial

outpost, and her parental history. Both had a kind of tarnished glamour for her.

Coupled with the hugely influential Band Aid campaign of the mid-1980s, which

had large numbers of idealistic, middle-class British youngsters heading for

African trouble spots (and often, Scroggins implies, just making matters worse

while they found themselves a mission in life), it made Sudan hard for McCune to

resist. Flirting with the possibility of travelling to Khartoum as a British aid

worker while at college, she was finally persuaded after falling in love with a

fellow student, Sudanese intellectual Ahmed Karadawi.

This brief affair was

the start of many flings with married African men that McCune conducted before

she finally met Riek Machar, the Sudanese warlord who started out supporting

John Garang, leader of the rebel Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA), before

fighting him for control. McCune met Riek while campaigning for kidnapped

Sudanese children, whom she maintained Garang took to train in his soldier

camps. Riek promised to help her -- and so began a relationship that would end

in marriage, pregnancy and death.

Scroggins is at pains to

emphasise that McCune's story is not simply the tale of a rather lost, romantic,

middle-class English girl who finds herself living a post-colonial dream . She

needs to take such pains -- McCune does not come across very well, with little

understanding of Sudan and its historical relationship with Britain. In one

instance we see her in a red mini-dress over a pair of flares, attending an

outdoor re-enactment of the killing of General George Gordon, while keeping

vodka and copies of Vogue with her in the midst of the most horrifying of

famines. In another, 'to her mother, she wrote rapturously of the Sudanese men

in their loose white turbans and long flowing gowns and of the hot breeze that

in Khartoum smelled of exotic spices'. Ignorant, vain, impulsive, naive,

generous, attractive, larger-than-life -- these are fair descriptions of her.

But are they enough to justify centering a book on her?

The answer lies in the

metaphor Scroggins uses at the beginning of her tale. Africa, she explains, is a

continent in which Britain likes to see itself reflected at its best:

philanthropic, encouraging, helpful, enlightening. It is a romantic reflection;

one McCune personalises to its greatest extent. The fact that while she was

gaily skipping round feeding centres and war-torn villages, Western capitalism

was dirtying that reflection with rounds of dodgy deals with the factions that

make up the crazy political map of Sudan, is something Scroggins exposes.

But McCune is not quite

grand enough to contain all that Sudan and its problems convey. And it is, of

course, ironic that British and US readers should learn about this vast country

and its history through the figure of a flawed British woman rather than any

Sudanese figures themselves. Scroggins acknowledges that calling the

conflagration of conflicts and massacres in recent Sudanese history Emma's War

is a contentious one. It is, alas, perhaps the easiest way of getting us in the

West to pay attention.

Civil war in

Sudan

African queen

Sep 26th

2002

From The Economist print edition

Emma's War: An Aid Worker, a

Warlord, Radical Islam, and the Politics of Oil—A True Story of Love and Death

in Sudan, by

Deborah Scroggins

Pantheon; 389 pages; $25. To be published in

Britain by HarperCollins in

March 2003

EMMA McCUNE was an

idealistic young British aid worker who spent much of the late 1980s

criss-crossing southern Sudan, then as now in the grip of civil war, dressed in

a red mini-skirt. Handing out charity pencils, books and blackboards to outdoor

schools financed by a high-minded Canadian lawyer, she cut a striking figure.

What really made McCune's

name, though, was her marriage in 1991 to a southern Sudanese warlord, Riek

Machar. McCune saw the marriage as a way of breaching the gap between white and

black. But to her fellow aid workers, it seemed that she had crossed an

invisible, and not altogether happy, line. When the Khartoum government began

bombing Sudanese refugees who were fleeing back into the country from Ethiopia,

the peaceable aid worker threw herself into Mr Machar's violent quest to take

over southern Sudan's rebel movement. In thrall to the man, she paid little

attention to the murder and kidnapping that was part of his quest for power. Two

years later, McCune was dead, crushed by an itinerant bush taxi near Nairobi.

She was 29 and pregnant.

Deborah Scroggins uses the

romantic aspects of this beautiful white woman's story to draw in unsuspecting

readers. But she has a sharp eye, and her real aim is to tease out the

inconsistencies of Emma McCune's brutally short life as a way of looking at how

foreigners through the ages have involved themselves in Sudan.

The humanitarians of the

19th century, many of whom were driven by urges half-hidden even from

themselves, have given way to modern famine-relief programmes. The donors who

fund them like the idea of giving pencils to small black children. However, they

averted their eyes when the hand-made sweaters donated by American knitting

circles in the late 1980s proved too warm for the Sudanese (they ended up being

worn as decorative hats) and when American food aid was used by the southern

Sudanese rebel movement, the SPLA, to maintain scores of camps where kidnapped

children were trained to fire guns. They looked away too whenever the Khartoum

government felt that foreign aid was making southern leaders like Riek Machar

too powerful, and retaliated by bombing feeding stations full of women and their

stick-thin children.

American oil companies pay

the northern Islamic government to try and gain access to the untapped oilfields

that lie in the south of the country. So far, the violence has stopped Chevron

and others from getting very far. At the same time, Christian groups in America

pour money into financing the southerners against the Muslim north. They believe

they are helping to establish a vanguard against the spread of Islam, but what

they are really doing is fuelling the civil war. “Emma's War” is about the

politics of the belly, and what happens when the fat white paunch meets the

swollen stomachs of the hungry in Africa. It is a sorry story, but Ms Scroggins

tells it awfully well.

By

Nat Hentoff

The Village Voice |

November 6, 2002

The acts of the

Government of Sudan . . . constitute genocide as defined by the [United Nations]

Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (1948).

—Sudan Peace Act, signed by the president of the United States, October 21, 2002

Since 1983, over 2 million

black, non-Muslim civilians have died during the civil war in Sudan. Blacks in

the south of the country have been fighting for self-determination and to end

the enslavement of women and children, ethnic cleansing, aerial bombardment of

schools and churches, and the creation of famine conditions—all of this by the

National Islamic Front government of the north.

Much of the world, including

the United States, has all along largely ignored what The Washington Post,

in a September 9 editorial, called "possibly the greatest humanitarian disaster

on Earth." But that newspaper and The New York Times, among other dailies

and weeklies, have only glancingly covered the disaster, and often with false

information.

In his review of the book

Emma's War in the October 20 New York Times, George Packer; note

author’s name is not given; it’s “Deborah Scroggins”-ap got to the essence of

continual media indifference to the horrors of the National Islamic Front

"jihad" against the blacks in the south: "The deaths of 10,000 southern Sudanese

by slaughter or 100,000 by starvation can occur with hardly a mention in

American newspapers." The other constant murders and gang rapes by the northern

militias have also slipped by the media.

Until mid-October, I was

convinced that only mass demonstrations and acts of civil disobedience here, the

kind that hastened the end of apartheid in South Africa, could move the White

House and Congress to do something—not in rhetoric but in law, with sanctions—to

end the ceaseless state terrorism in Sudan. However, an extraordinary historic

coalition of abolitionists has in recent years put such unremitting pressure on

Bush and Congress that at last, on October 9, a unanimous Senate passed the

Sudan Peace Act. It had already been approved in the House on October 7 by a

vote of 359 to 8.

Among those in the coalition

are black churches around the country, white evangelicals, the Boston-based

American Anti-Slavery Group, the Congressional Black Caucus, Chuck Colson's

Prison Fellowship, the Institute on Religion and Democracy, civil rights leaders

such as Joe Madison and Walter Fauntroy, conservatives led by Michael Horowitz

of the Hudson Institute and Senator Sam Brownback of Kansas, Jewish

organizations, and others. Missing all these years were nearly all of the

Democratic leadership in Congress, most editorial writers and columnists, and,

with few exceptions, American broadcast and cable television. Next week: the

details of the Sudan Peace Act, including sanctions for noncompliance with the

law. Also, why this is an important beginning of the end for these atrocities;

but also why continuous pressure on the White House and Congress—and

Khartoum—will be essential. Keep in mind, however, that with the United States

having found Khartoum guilty of actual genocide, a heavy obligation now falls on

the White House and Congress to follow through.

Article One of the UN

Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide states

clearly: "The Contracting Parties confirm that genocide, whether committed in

time of peace or in time of war, is a crime under international law which

they undertake to prevent and to punish." (Emphasis added. We have now

contracted to do that.

Should the slave raids, the

ethnic cleansing, and the gang rapes continue, the leaders of the government of

Sudan could be brought before the International War Crimes Tribunal. However,

all the abolitionists in the American coalition will have to ensure that

Congress and the White House bring those indictments, if necessary, before the

War Crimes Tribunal.

Meanwhile, from Christian

Solidarity International—which, with the American Anti-Slavery Group, has

redeemed thousands of slaves—there is this report from Khartoum after the

passage of the Sudan Peace Act:

"The National Assembly in

Khartoum urged Arabs and Muslims throughout the world to denounce the law,

calling it 'a breach of Sudan's sovereignty' . . . The Sudanese chargé

d'affaires in Washington, Dr. Harun Khidir, blamed 'members of the extremist

Christian right groups and a group of the black masses' for pushing the Sudan

Peace Act through Congress. . . .

"Following congressional

approval of the legislation, Islamist officials organized a mass demonstration

in Khartoum in support of Iraqi President Saddam Hussein, during which an effigy

of President Bush, wrapped in American and Israeli flags and labeled 'the corpse

of imperialism,' was torn to shreds and burnt." (The latter story was reported

by Agence France-Presse on October 16).

Colin Powell might have been

added to the bonfire had the slavemasters known—as I have found out—that Powell,

behind the scenes, was an important factor in getting the Bush administration to

finally move on abolishing slavery in Sudan. Powell is the man Harry Belafonte

calls "a house slave." In all the years I've been involved in this story, I do

not recall Belafonte being an active, persistent member of the New Abolitionists

working to liberate the blacks of Sudan—although he has been prominent in other

human rights causes. Powell has been significantly involved in the anti-slavery

movement.

Actually, when I started

writing about the slaves of Sudan in the Voice about six years ago, the

beginning of the New Abolitionist movement was driven by the American

Anti-Slavery Group, headed by Charles Jacobs, who first told me of the horrors

in Sudan.

There was also a young

graduate student at Columbia University, Sam Cotton, who traveled to black

churches and newspapers around the country to spread the liberating word. In

Denver, Barbara Vogel told her fifth-grade class that slavery was not dead, and

those kids began collecting money to free slaves in Sudan through Christian

Solidarity International. Other schoolchildren around the country joined in.

Eric Reeves took two years

off from teaching Shakespeare and Milton at Smith College to focus invaluably on

research and advocacy, including testimony before Congress on the National

Islamic Front's barbarity in Sudan. Donald Payne led the Congressional Black

Caucus's involvement, with the later help of Eleanor Holmes-Norton. Instrumental

members of the House included Frank Wolf, Spencer Bachus, and Tom Trancedo.

There were many more. "And,"

John Eibner of Christian Solidarity International told me on the day Bush signed

the Sudan Peace Act, "don't forget all the anonymous people who signed pledge

cards, contributed money, and prayed for the freedom of the slaves. We'll never

know who they were, but the Sudan Peace Act couldn't have happened without

them."

The white

woman's burden

(Filed:

02/03/2003)

Justin

Marozzi reviews Emma's War: Love, Betrayal and Death in the Sudan by Deborah

Scroggins

The

one person who would have been particularly delighted by Deborah's Scroggins's

Emma's War, I suspect, was the flamboyant young woman who is its subject.

Emma McCune

was many things - aid worker, adventuress, Sudanese warlord's wife, drama queen

- but a writer she was most certainly not. Although she saw her life as

compellingly interesting, the writer-friends she approached for help when she

attempted to write her autobiography did not. The pages she showed them were

trite and sentimental and as for the subject herself: "There isn't anything

there but a black man boffing a white woman," one friend remarked, to her great

irritation. A rather mean verdict, perhaps, but not entirely wide of the mark.

There is no

need to question the purity of McCune's motives for choosing to make her life in

war-torn southern Sudan. Like so many of what Deborah Scroggins calls the

"humanitarian tribe" of aid workers, journalists, and other thrill-seekers and

hangers-on, she was carried along by both a taste for adventure and an

idealist's faith in "doing good" in that benighted continent. Whether one

outweighed the other is immaterial. There is no crime in not wanting to marry a

stockbroker and live in suburbia.

What is more

interesting is the process by which the young Englishwoman evolved from

high-minded educational aid worker distributing pencils and blackboards to

fledgling schools in the bush, to wife of the guerrilla warlord Riek Machar -

and blind to the atrocities her idealised husband and his soldiers in the Sudan

People's Liberation Army committed.

A sexual

frisson had accompanied her first meeting - to discuss educational needs in SPLA

territory - with the charismatic leader. His penis ultimately proved more

compelling than her pencils - white men's genitals she dismissed as "slugs". The

boyfriend she had persuaded to make the arduous drive to Machar's camp was

summarily dismissed. After a last tangle with him under the stars, she told him

she loved another man.

McCune's

transformation understandably irked her former colleagues in the aid sector and,

more seriously, undermined relief operations in southern Sudan, especially when

she took to broadcasting rebel statements on United Nations radio. Besides, as

Scroggins acknowledges, it was ludicrous for a junior relief worker to call for

a "political solution" to the interminable conflict during her urgent broadcasts

in the field.

Although

there is a nagging suspicion that the marriage to a warlord was always something

of an exercise in one-upmanship in the unconventionality stakes, one should not

be too harsh on McCune. Her compassion for the poor, weak and dying around her

was undoubtedly genuine and for the short time she lived in Sudan she was a

popular figure.

It may be

that when she crossed the line from relief worker to partisan rebel commander's

wife she was leaving the hypocrisies of the aid sector behind her, but if that

were the case they were quickly replaced by the cy nicism of war and killing.

Her own end was arbitrary and abrupt: she was killed in a road accident when she

was 29.

Although this

book is probably twice as long as it should be, Scroggins is to be congratulated

for making the story of Emma McCune's ill-fated foray into Africa such a good

read. The Englishwoman has been given a posthumous importance her short life