8-3-2005

FLEUR ADCOCK

(b. 1934)

Bio and

bibliography

|

MIRAMAR

Miramar?

No, surely not -- it can't be:

the cream, clinker-built walls, the pepper tree,

the swan-plants under my bedroom window...

But if it is, I'll open the back door

to the sun porch, with its tang of baked wood.

You'll be lying propped on the shabby couch,

writing; you won't be pleased to see me,

home from school already, with my panama

and my teenage grumps, though you'll pretend

you're a gracious mother, and I a loving daughter.

After the chiropractor's fixed your back

and growing up improved my temper,

we'll learn to be good friends for forty years,

most of them spent apart, vocal with letters:

glad of each other, over all the distances --

until this one, that telescopes your past,

compacting the whole time from postwar England

to your present house into a flattened slice

of Lethe; tidily deleting my teens

from your tangled brain; obliterating Miramar.

|

|

|

|

INDEX:

A Surprise

in the Peninsula

Advice to a Discarded Lover

Against Coupling

Double-Take

Flowers of the Field

For Heidi With Blue Hair

Future Work

Glenshane

Happy Ending

Influenza

Leaving the Tate

Londoner

Miramar

Mornings After

On the Border

Poem Ended by a Death

Proposal for a Survey

Revision

The Prize-Winning Poem

Things

Tokens

Weathering

| |

When you dyed your hair blue

(or, at least ultramarine

for the clipped sides, with a crest

of jet-black spikes on top)

you were sent home from school

because, as the headmistress put it,

although dyed hair was not

specifically forbidden, yours

was, apart from anything else,

not done in the school colours.

Tears in the kitchen, telephone-calls

to school from your freedom-loving father:

'She's not a punk in her behaviour;

it's just a style.' (You wiped your eyes,

also not in a school colour.)

'She discussed it with me first -

we checked the rules.' 'And anyway, Dad,

it cost twenty-five dollars.

Tel them it won't wash out -

not even if I wanted to try.

It would have been unfair to mention

your mother's death, but that

shimmered behind the arguments.

The school had nothing else against you;

the teachers twittered and gave in.

Next day your black friend had hers done

in grey, white and flaxen yellow -

the school colours precisely:

an act of solidarity, a witty

tease. The battle was already won. |

A HEIDI COI CAPELLI BLU

Quando ti sei tinta i capelli di blu

(o

meglio, oltremare

sui

lati rasati, con una cresta

di spuntoni neri in cima)

ti hanno mandato a casa

da scuola

perchè, per come l'ha

messa la preside,

anche se i capelli tinti

non sono

esplicitamente vietati, i

tuoi

non erano, comunque,

nei colori della scuola.

Lacrime in cucina,

tuo padre il liberale che

telefona a scuola:

"Non è punk dentro, è

solo una moda".

(Tu ti sei asciugata gli

occhi,

anche quelli non hanno i

colori della scuola).

"Prima ne hai parlato con

me ...

abbiamo controllato le

regole". "E comunque,

papà,

è costato venticinque

dollari.

Digli che non viene via

nemmeno se volessi

provarci".

Sarebbe stato scorretto

ricordare

la morte di tua madre, ma

la cosa

balenò dietro le

discussioni.

La scuola non aveva

nient'altro contro di te;

gli insegnanti ciarlarono

e si arresero.

Il giorno dopo la tua

amica nera si era

tinta i suoi

di grigio, bianco e

giallo pallido

esattamente i colori

della scuola:

un atto di solidarietà,

una sapiente

presa in giro.

La battaglia era già

vinta. |

|

Double-Take

You

see your next-door neighbour from above,

from an upstairs window, and he reminds you

of your ex-lover, who is bald on top,

which you had forgotten. At ground level

there is no resemblance. Next time you chat

with your next-door neighbour, you are relieved

to find that you don’t fancy him.

A

week later you meet your ex-lover

at a party, after more than a year.

He reminds you of (although only slightly)

of your next-door neighbour. He has a paunch

like your neighbour’s before he went on that diet.

You remember how much you despise him.

He

behaves as if he’s pleased to see you.

When you leave (a little earlier

than you’d intended, to get away)

he gives you a kiss which is more than neighbourly

and says he’ll ring you. He seems to mean it.

How odd! But you are quite relieved

to find that you don’t fancy him.

Unless you do? Or why that sudden

something, once you get outside

in the air? Why are your legs prancing

so cheerfully along the pavement?

And what exactly have you just remembered?

You go home cursing chemistry.

|

A

scoppio ritardato

Vedi

dall’alto l’uomo della porta accanto,

da una finestra al piano di sopra, e ti ricorda

il tuo ex: anche lui ha la chierica,

questo lo avevi dimenticato. Visti dal basso

non si somigliano affatto. La prossima volta che parli

con l’uomo della porta accanto, sarà un sollievo

scoprire che non sei attratta da lui.

Dopo

una settimana incontri il tuo ex

a una festa, dopo più di un anno che non lo vedi.

Ti fa venire in mente (ma solo un poco)

l’uomo della porta accanto. Ha la stessa pancetta

del tuo vicino prima che facesse quella dieta.

Ti ricordi di quanto lo detesti.

Si

comporta come se gli facesse piacere vederti.

Quando vai via (un po’ prima

di quanto avessi pensato, per scappare)

ti dà un tipo di bacio che non è d’uso tra vicini

e dice che ti chiamerà. E sembra deciso a farlo.

Che strano! Ma è un vero sollievo

scoprire che non sei attratta da lui.

O forse

lo sei? Altrimenti perché

quel nonsoché improvviso, una volta fuori

all’aria? Perché mai le tue gambe saltellano

allegre lungo il marciapiedi?

Cosa ti sarà mai venuto in mente?

Torni a casa maledicendo la chimica.

|

|

| |

Things

There

are worse things than having behaved foolishly in public.

There

are worse things than these miniature betrayals,

committed or endured or suspected; there are worse things

than

not being able to sleep for thinking about them.

It is

5 a.m. All the worse things come stalking in

and

stand icily about the bed looking worse and worse

and

worse.

|

|

|

A snail is climbing up

the window-sill

Into your room, after a night of rain.

You call me in to see and I explain

That it would be unkind to leave it there:

It might crawl to the floor; we must take care

That no one squashes it. You understand,

And carry it outside, with careful hand,

To eat a daffodil.

I see, then, that a kind of faith prevails:

Your gentleness is moulded still by words

From me, who have trapped mice and shot wild birds,

Your closest relatives and who purveyed

The harshest kind of truth to many another,

But that is how things are: I am your mother,

And we are kind to snails.

|

|

|

| |

Against

Coupling

I write in praise of the solitary act:

of not feeling a trespassing tongue

forced into one's mouth, one's breath

smothered, nipples crushed against the

rib-cage, and that metallic tingling

in the chin set off by a certain odd nerve:

unpleasure. Just to avoid those eyes

would help-

such eyes as a young girl draws life from,

listening to the vegetal

rustle within her, as his gaze

stirs polypal fronds in the obscure

sea-bed of her body, and her own eyes blur

. There is much to be said for abandoning

this no longer novel exercise-

for now 'participating in

a total experience'-when

one feels like the lady in Leeds who

had seen The Sound Of Music eighty-six times;

or more, perhaps, like the school drama

mistress

producing A Midsummer Night's Dream

for the seventh year running, with

yet another cast from 5B.

Pyramus and Thisbe are dead, but

the hole in the wall can still be troublesome.

I advise you, then, to embrace it without

encumberance. No need to set the scene,

dress up (or undress), make speeches.

Five minutes of solitude are

enough-in the bath, or to fill

that gap between the Sunday papers and lunch.

|

|

|

Odd

how the seemingly maddest of men -

sheer loonies, the classically paranoid

violently possessive about their secrets,

whispered after from corners, terrified

of poison in their coffee, driven frantic

(whether for or against him) by discussion of God

peculiar, to say the least, about their mothers -

return to their gentle senses in bed.

Suddenly straightforward, they perform

with routine confidence, neither afraid

that their partner will turn and bite their balls off

nor groping under the pillow for a razor blade;

eccentric only in their conversation,

which rambles on about the meaning of a word

they used in an argument in 1969,

they leave their women grateful, relieved, and bored.

|

|

|

| |

Happy

Ending

After they had not made love

she pulled the sheet up over her eyes

until he was unbottoning his shirt:

not shyness for their bodies-those

they had willingly displayed-but a frail

endeavour to apologise.

Later, though, drawn together by

a distaste for such 'untidy ends'

they agreed to meet again; whereupon

they giggled, reminisced, held hands

as though what they had made was love-

and not that happier outcome, friends.

|

|

|

Weathering

My face catches the wind

from the snow line

and flushes with a flush

that will never wholly settle.

Well, that was a metropolitan vanity,

wanting to look young forever, to pass.

I was never a pre-Raphaelite beauty

and only pretty enough to be seen

with a man who wanted to be seen

with a passable woman.

But now that I am in love

with a place that doesn't care

how I look and if I am happy,

happy is how I look and that's all.

My hair will grow grey in any case,

my nails chip and flake,

my waist thicken, and the years

work all their usual changes.

If my face is to be weather beaten as well,

it's little enough lost

for a year among the lakes and vales

where simply to look out my window

at the high pass

makes me indifferent to mirrors

and to what my soul may wear

over its new complexion.

|

|

|

| |

Tokens

The sheets have been laundered clean

of our joint essence - a compound,

not a mixture; but here are still

your forgotten pipe and tobacco,

your books open on my table,

your voice speaking in my poems.

|

|

|

Glenshane

Abandoning all my principles

I travel by car with you for days,

eat meat from tins, drink pints of Guinness,

smoke too much, and now on this pass

higher than all our settled landscapes

feed salted peanuts into your mouth

as you drive at eighty miles an hour.

|

|

|

| |

Future

Work

'Please send future work'

- Editor's note on a rejection slip.

It is going to be a splendid summer.

The apple tree will be thick with golden russets

expanding weightily in the soft air.

I shall finish the brick wall beside the terrace

and plant out all the geranium cuttings.

Pinks and carnations will be everywhere.

She will come out to me in the garden,

her bare feet pale on the cut grass,

bringing jasmine tea and strawberries on a tray.

I shall be correcting the proofs of my novel

(third in a trilogy - simultaneous publication

in four continents); and my latest play

will be in production at the Aldwych

starring Glenda Jackson and Paul Scofield

with Olivier brilliant in a minor part.

I shall probably have finished my translations

of Persian creation myths and the Pre-Socratics

(drawing new parallels) and be ready to start

on Lucretius. But first I'll take a break

at the chess championships in Manila -

on present form, I'm fairly likely to win.

And poems? Yes, there will certainly be poems:

they sing in my head, they tingle along my nerves.

It is all magnificently about to begin.

|

|

|

The

Prize-Winning Poem

It will be typed, of course, and not all in capitals: it will use upper and

lower case

in the normal way; and where a space is usual it will have a space.

It will probably be on white paper, or possibly blue, but almost certainly

not pink.

It will not be decorated with ornamental scroll-work in coloured ink,

nor will a photograph of the poet be glued above his or her name,

and still less a snap of the poet's children frolicking in a jolly game.

The poem will not be about feeling lonely and being fifteen

and unless the occasion of the competition is a royal jubilee it will not be

about the queen.

It will not be the first poem the author has written in his life

and will probably not be about the death of his daughter, son or wife

because although to write such elegies fulfils a therapeutic need

in large numbers they are deeply depressing for the judges to read.

The title will not be 'Thoughts' or 'Life' or 'I Wonder Why'

or 'The Bunny-rabbit's Birthday Party' or 'In Days of Long Gone By'.

'Tis and 'twas, o'er and e'er, and such poetical contractions will not be

found

in the chosen poem. Similarly cliches will not abound:

dawn will not herald another bright new day, nor dew sparkle like diamonds

in a dell,

nor trees their arms upstretch. Also the poet will be able to spell.

Large meaningless concepts will not be viewed with favour: myriad is out;

infinity is becoming suspect; aeons and galaxies are in some doubt.

Archaisms and inversions will not occur; nymphs will not their fate bemoan.

Apart from this there will be no restrictions upon the style or tone.

What is required is simply the masterpiece we'd all write if we could.

There is only one prescription for it: it's got to be good.

|

|

|

| |

Londoner

Scarcely two hours back in the country

and I'm shopping in East Finchley High Road

in a cotton skirt, a cardigan, jandals -

or flipflops as people call them here,

where February's winter. Aren't I cold?

The neighbours in their overcoats are smiling

at my smiles and not at my bare toes:

they know me here.

I

hardly know myself,

yet. It takes me until Monday evening,

walking from the office after dark

to Westminster Bridge. It's cold, it's foggy,

the traffic's as abominable as ever,

and there across the Thames is County Hall,

that uninspired stone body, floodlit.

It makes me laugh. In fact, it makes me sing.

|

|

|

Influenza

Dreamy with illness

we are Siamese twins

fused at the groin

too languid to stir.

We sprawl transfixed

remote from the day.

The window is open.

The curtain flutters.

Epics of sound-effects

ripple timelessly:

a dog is barking

in vague slow bursts;

cars drone; someone

is felling a tree.

Forests could topple

between the axe-blows.

Draughts idle over

our burning faces

and my fingers over

the drum in your ribs.

You lick my eyelid:

the fever grips us.

We shake in its hands

until it lets go.

Then you gulp cold water

and make of your mouth

a wet cool tunnel.

I slake my lips at it.

|

|

|

| |

Revision

It has to be learned afresh

every new start or every season,

revised like the languages that faltered

after I left school or when I stopped

going every year to Italy. Or

like how to float on my back, swimming,

not swimming, ears full of sea-water;

like the taste of the wine at first communion

(because each communion is the first);

like dancing and how to ride a horse -

can I still? Do I still want to?

The sun is on the leaves again;

birds are making rather special noises;

and I can see for miles and miles

even with my eyes closed.

So yes: teach it to me again.

|

|

|

Advice

to a Discarded Lover

Think, now: if you have found a dead bird,

not only dead, not only fallen,

but full of maggots: what do you feel -

more pity or more revulsion?

Pity is for the moment of death,

and the moments after. It changes

when decay comes, with the creeping stench

and the wriggling, munching scavengers.

Returning later, though, you will see

a shape of clean bone, a few feathers,

an inoffensive symbol of what

once lived. Nothing to make you shudder.

It is clear then. But perhaps you find

the analogy I have chosen

for our dead affair rather gruesome -

too unpleasant a comparison.

It is not accidental. In you

I see maggots close to the surface.

You are eaten up by self-pity,

crawling with unlovable pathos.

If I were to touch you I should feel

against my fingers fat, moist worm-skin.

Do not ask me for charity now:

go away until your bones are clean.

|

|

|

| |

On The

Border

Dear posterity, it's 2 a.m.

and I can't sleep for the smothering heat,

or under mosquito nets. The others

are swathed in theirs, humid and sweating,

long white packets on rows of chairs

(no bunks. The building isn't finished).

I prowled in the dark back room for water

and came outside for a cigarette

and a pee in waist-high leafy scrub.

The moon is brilliant: the same moon,

I have to believe, as mine in England

or theirs in the places where I'm not.

Knobbly trees mark the horizon,

black and angular, with no leaves:

blossoming flame-trees; and behind them

soft throbbings come from the village.

Birds or animals croak and howl;

the river rustles; there could be snakes.

I don't care. I am standing here,

posterity, on the face of the earth,

letting the breeze blow up my nightdress,

writing in English, as I do,

in all this tropical non-silence.

Now let me tell you about the elephants.

|

|

|

Leaving

the Tate

Coming out with your clutch of postcards

in a Tate gallery bag and another clutch

of images packed into your head you pause

on the steps to look across the river

and there's a new one: light bright buildings,

a streak of brown water, and such a sky

you wonder who painted it - Constable? No:

too brilliant. Crome? No: too ecstatic -

a madly pure Pre-Raphaelite sky,

perhaps, sheer blue apart from the white plumes

rushing up it (today, that is,

April. Another day would be different

but it wouldn't matter. All skies work.)

Cut to the lower right for a detail:

seagulls pecking on mud, below

two office blocks and a Georgian terrace.

Now swing to the left, and take in plane-trees

bobbled with seeds, and that brick building,

and a red bus...Cut it off just there,

by the lamp-post. Leave the scaffolding in.

That's your next one. Curious how

these outdoor pictures didn't exist

before you'd looked at the indoor pictures,

the ones on the walls. But here they are now,

marching out of their panorama

and queuing up for the viewfinder

your eye's become. You can isolate them

by holding your optic muscles still.

You can zoom in on figure studies

(that boy with the rucksack), or still lives,

abstracts, townscapes. No one made them.

The light painted them. You're in charge

of the hanging committee. Put what space

you like around the ones you fix on,

and gloat.

Art multiplies itself.

Art's whatever you choose to frame.

|

|

|

| |

Mornings After

The

surface dreams are easily remembered:

I

wake most often with a comforting sense

of

having seen a pleasantly odd film—

nothing too outlandish or too intense;

of

having, perhaps, befriended animals,

made

love, swum the Channel, flown in the air

without wings, visited Tibet or Chile:

simple childish stuff. Or else the rare

recurrent horror makes its call upon me:

I

dream one of my sons is lost or dead,

or

that I am trapped in a tunnel underground;

but

my scream is enough to recall me to my bed.

Sometimes, indeed I congratulate myself

on

the nice precision of my observation:

on

having seen so vividly a certain

colour; having felt the sharp sensation

of

cold water on my hands; the exact taste

of

wine or peppermints. I take pride

in

finding all my senses operative

even

in sleep. So, with nothing to hide,

I

amble through my latest entertainment

again, in the bath or going to work,

idly

amused at what the night has offered;

unless this is a day when a sick jerk

recalls to me a sudden different vision:

I

see myself inspecting the vast slit

of a

sagging whore; making love with a hunchbacked

hermaphrodite; eating worms or shit;

or

rapt upon necrophily or incest.

And

whatever loathsome images I see

are

just as vivid as the pleasant others.

I

flush and shudder: my God, was that me?

Did

I invent so ludicrously revolting

a

scene? And if so, how could I forget

until this instant? And why now remember?

Furthermore (and more disturbing yet)

are

all my other forgotten dreams like these?

Do

I, for hours of my innocent nights,

wallow content and charmed through verminous muck,

rollick in the embraces of such frights?

And

are the comic or harmless fantasies

I

wake with merely a deceiving guard,

as

one might put a Hans Andersen cover

on a

volume of the writing of De Sade?

Enough, enough. Bring back those easy pictures,

Tibet or antelopes, a seemly lover,

or

even the black tunnel. For the rest,

I do

not care to know.

Replace the

cover.

|

|

| |

A SURPRISE IN THE PENINSULA

When I

came in that night I found

the

skin of a dog stretched flat and

nailed

upon my wall between the

two

windows. It seemed freshly killed –

there

was blood at the edges. Not

my

dog: I have never owned one,

I

rather dislike them .(Perhaps

whoever did it knew that.) It

was a

light brown dog, with smooth hair;

no

head, but the tail still remained.

On the

flat surface of the pelt

was

branded the outline of the

peninsula, singed in thick black

strokes into the fur: a coarse map.

The

position of the town was

marked

by a bullet-hole, it went

right

through the wall. I placed my eye

to it,

and could see the dark trees

outside the house, flecked with moonlight.

I

locked the door the, and sat up

all

night, drinking small cups of the

bitter

local coffee. A dog

would

have been useful, I thought, for

protection. But perhaps the one

I had

been given performed that

function; for no one came that night,

not

for three more. On the fourth day

it was

time to leave. The dog-skin

still

hung on the wall, stiff and dry

by

now, the flies and the smell gone.

Could

it, I wondered, have been meant

not as

a warning, but a gift?

And,

scarcely shuddering, I drew

the

nails out and took it with me.

|

|

|

PROPOSAL FOR A SURVEY

Another poem about a Norfolk church,

a neolithic circle, Hadrian's Wall?

Histories and prehistories: indexes

and bibliographies can't list them all.

A map of Poets' England from the air

could show not only who and when but where.

Aerial photogrammetry's the thing,

using some form of infra-red technique.

Stones that have been so fervently described

surely retain some heat. They needn't speak:

the cunning camera ranging in its flight

will chart their higher temperatures as light.

We'll see the favoured regions all lit up -

the Thames a Þery vein, Cornwall a glow,

Tintagel like an incandescent stud,

most of East Anglia sparkling like Heathrow;

and Shropshire luminous among the best,

with Offa's Dyke in diamonds to the west.

The Lake District will be itself a lake

of patchy brilliance poured along the vales,

with somewhat lesser splashes to the east

across Northumbria and the Yorkshire dales.

Cities and churches, villages and lanes,

will gleam in sparks and streaks and radiant stains.

The lens, of course, will not discriminate

between the venerable and the new;

Stonehenge and Avebury may catch the eye

but Liverpool will have its aura too.

As well as Canterbury there'll be Leeds

and Hull criss-crossed with nets of glittering beads.

Nor will the cool machine be influenced

by literary fashion to reject

any on grounds of quality or taste:

intensity is all it will detect,

mapping in light, for better or for worse,

whatever has been written of in verse.

The dreariness of eighteenth-century odes

will not disqualify a crag, a park,

a country residence; nor will the rant

of satirists leave London in the dark.

All will shine forth. But limits there must be:

borders will not be crossed, nor will the sea.

Let Scotland, Wales and Ireland chart themselves,

as they'd prefer. For us, there's just one doubt:

that medieval England may be dimmed

by age, and all that's earlier blotted out.

X-rays might help. But surely ardent rhyme

will, as it's always claimed, outshine mere time?

By its own power the influence will rise

from sites and settlements deep underground

of those who sang about them while they stood.

Pale phosphorescent glimmers will be found

of epics chanted to pre-Roman tunes

and poems in, instead of about, runes.

|

|

|

| |

Poem

Ended by a Death

They will wash all my kisses and fingerprints off you

and my tearstains--I was more inclined to weep

in those wild-garlicky days--and our happier stains,

thin scales of papery silk...Fuck that for a cheap

opener; and false too--any such traces

you pumiced away yourself, those years ago

when you sent my letters back, in the week I married

that anecdotal ape. So start again. So:

They will remove the tubes and drips and dressings

which I censor from my dreams. They will, it is true,

wash you; and they will put you into a box.

After which whatever else they may do

won't matter. This is my laconic style.

You praised it, as I praised your intricate pearled

embroideries, these links laced us together,

plain and purl across the ribs of the world...

|

|

|

FLOWERS OF THE FIELD

At

the blood-test laboratory

people come out one by one

each

carrying a test-tube of blood

like

a lighted candle.

(Could you carry a poem in your hand like that

without spilling a drop?)

Prickly smells, faces anonymous

as

camomile, but plucked out and chosen.

The

colours show up as clearly

as

in a painting.

(Remember the well-known question:

“Which would you save from a fire, a famous picture

or a

man who hadn’t long to live?”)

Reflections from the test-tubes make face blush red,

illuminate rough hands.

This

is surely a picture that must be saved:

a

procession of poppies

through the long corridors,

advancing, invading – making no mistake

about how long they’ve got.

|

|

|

Other poems online:

Final touch

Fleur Adcock has been writing poems since she was five.

But now, many books of verse and twists and turns in her life later, she has

fallen out of love with poetry and found a new passion. By Sally Vincent

Saturday July

29, 2000

The Guardian

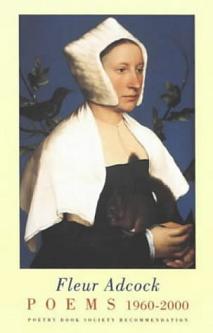

The book is an epitaph of a thing. POEMS 1960-2000, as

though the poet is meant to be dead. Since she clearly is not, it must be more

of a symbol of institutionalised acceptability, like an OBE. Exactly like that.

One afternoon we had them both out, the book and the medal and gave them long

shrift. She was saying something about liking the finality of it, the

completion, sounding defiant and fatalistic at the same time, when the vicar's

wife telephoned. Would she be an angel and read the lesson this upcoming Sunday

instead of next? Yes, yes, of course she will. Sunday it is, then, lovely, and

she laughed the girlish laugh of a particularly dependable monitoress.

Meanwhile, I

have inspected the picture on the cover. "From a painting by Hans Holbein the

Younger," it says, "1497-1543 A Lady With A Squirrel And A Starling": a solid

female citizen with introspective gaze, hands folded piously around a chain that

inches along her wrist and - good grief - enslaves the chubby squirrel to her

bosom. Pure Adcockian shock tactic, I reckon, a sort of pictorial version of

something wickedly sharp that suddenly leaps from the fastidious formality of

rhyme and meter and bites you on the bum.

You can see why

they value her vocal contribution at the lectern. Adcock's voice is literally

ethereal, so light and pure it seems to be emanating from altitude. In front of

you is this pretty, faded tapestry of a woman, smiling hospitably and bringing

tea and ashtrays, while what she's saying floods your auditory system as though

she is also behind you. No, she says, we hardly ever see squirrels in East

Finchley nowadays. Do you take sugar? They're not very nice, you know. They're

carnivores. Didn't you know that? Oh, yes, they creep about in trees looking for

birds' nests and when they find one they look over the nestlings and finger them

out, one by one, and gobble them up. First they nibble off their tiny feet, then

they scoff the lot. She has this on the eye-witness authority of a friend of the

old gentleman who lives next door and devotes himself to trapping the little

murderers and slaughtering them wholesale. First he tried stabbing, but that

didn't work, so now he drowns them. That does the trick.

Lilting on from

the ether, she returns to the matter in hand. Ah, yes, her OBE, still in its

box. She had, of course, toyed with the idea of turning it down on the grounds

of the silly, school-prize-day elitism of the honours system. But then she

thought if she did that she'd only go around telling everyone, which,

perversely, would have a similarly unattractive effect. So she bought a hat and

a smart suit which would afterwards do for funerals, and turned up at the palace

for the big reward. Now she thinks back on it, it was all quite enthralling. You

line up with a few hundred other worthies, long-serving town clerks and lollipop

ladies and so forth, while a man sticks a hook thing into your brand new lapel

and gives you the drill. Speak when you're spoken to, go when your time is up.

Her Majesty will make it abundantly clear when that is.

I have to stand

up for this bit. You be me, she says, I'll be the Queen. Right. Her Majesty

comes before you, so, another man with a clipboard tells her who you are, then

she tells you who you are, loops the gong on your hook, takes your right hand in

hers, so, tells you well done and, still holding your hand, gives you an

almighty shove backwards. Like so. A serious shove. If you're not well braced on

your pins you could do a purler. We give each other the royal shove of honour so

as to be quite clear in our minds as to the precise toppling potential of Her

Majesty's dismissal technique.

There is no

mockery intended. To Fleur Adcock, things are only what they are; sad or funny

or painful or puzzling or silly or wonderful or any of a million, trillion

things, none of which require to be tainted by judgmental inference. She exudes

an air of serene pragmatism that punctuates itself with floaty giggles or

helpless sighs rather than analysis or rationalisation. She is all of a piece,

outside in, inside out. Small talk, life experience, the most bizarre

machinations of her psyche are all the same to her.

At our first

meeting, she lead me into her unreconstructed scullery and talked about the

charm of Victorian plumbing and the ludicrous inflation of real-estate values in

north London. Then of the arrival, from New Zealand this morning, of her

sister's autobiography, in which she has read a faintly dismaying account of

herself in general and, in particular, her hands. This last triggers the memory

of Tiger-Spider, the lost companion of last summer, who wove her wondrous web in

the scullery cupboard. She was large and her legs were striped black and gold

and hairy and, as she grew old and seemed to be failing, Fleur bought cos

lettuces for their greenflies and blew them on her web to supplement her diet.

One day, Tiger-Spider came out of her cupboard and was observed legging it

across the ceiling, alarmingly close to where she might topple into the sink and

perish.

Fleur reached

up, took Tiger-Spider into her hands and carried her home to safety. "Don't you

think it extraordinary?" she said, "to have been together for so long and never

to have touched her before?" And she looked at her hands, small and pale and

sweetly cupped as when they cradled the late lamented arachnid. She sighed and

winced. Her sister has written that, once upon a time, when they were both

young, they compared hands and Fleur's were judged to be less pleasing. She is

at a loss. There is no end to the vicissitudes of sibling rivalry.

The point is,

you don't get it at the time. Your heart is broken and you don't even know it.

It's something you have to work out later. She knows the precise moment now, as

we climb the stairs to her study, so it comes, all cheerfully matter-of-fact

from between her shoulder blades. "My heart was broken when my sister was born."

And there on the landing she said that nobody really understands the visceral

anguish of the first-born when the next one arrives. She was only 18 months old.

Everything was perfect, then they kicked her in the teeth. Clearly it was

because she wasn't good enough, so they went out and got themselves another one.

A cuter one. You don't recover from that sort of betrayal. Sixty-two years it

has taken her to work that out. After that, though, rejection is a piece of

cake. You learn detachment. Even so, it's a bit much when you're supposed to be

the big girl, protector of the little one, and you've just had the biggest shock

of your life.

She was five

years old when the big test came. Her parents had come to England from New

Zealand, where she was born. The second world war was on the cards and they,

good people that they were, meant to dig ditches for the war effort. They

settled briefly in Sidcup, then evacuated their daughters to distant relations

on a Leicestershire farm.

In England,

Fleur found her spiritual home. Not to put too fine a point on it, she loved the

weather. The seasons were real and distinct one from another. Winters were real

winters with snow and summers were real summers and the skies changed face a

million times a day and, putting it in a nutshell, there were primroses. In

those first, halcyon days, she was a good big sister. Without a mummy and daddy

to fight for, there was nothing to be cross about. Being the first to read, she

did the decent thing and read aloud to the baby sister, good as gold. The worst

she did was to charge a penny each for making up a new William story. "William

and Ginger went for a walk. Just as they came to the old barn, William noticed .

. ." And so on. She didn't get nasty till later.

In common with

most children of her computer-less generation, Fleur seemed to have been born

with a sort of literacy racial memory. Looking back, she has to presume her

parents taught her to read and write, since they were both teachers, but her

abiding memory is of being able to discern the sound of written words before she

had the vocabulary to comprehend their meaning.

For instance,

she'd be sitting on the bus, aged four, merrily reading "Do not spit. Penalty

£5" off the wall and wondering how you go about spitting penalty and in what way

it differed from ordinary spit. She liked to make sense of things, she wanted

things to fit and, if at all possible, to rhyme. She had a huge book of nursery

rhymes, as thick as it was square, and her mother would recite grown-up poems to

her; Drinkwater, Brooke, Monroe. "Moonlit apples," she croons now. And "I will

lie in the grass and howl for them/Your green glass beads." Adcock wrote her

first poem when she was five. The silvered voice delivers it now, with no less

reverence than she'd attribute to Wordsworth:

"Hurry up and

go to bed

For all night long you cuddle Ted."

And points out,

in fairness, that she didn't really have a teddy bear, she had a soft-toy dog

called Bob, but since Bob doesn't rhyme with bed she made Ted up. Later, she

added a further couplet to that first fine, careless rapture.

"We'll have

good sleep all through the night

And when dawn comes we'll see the light."

By the time she

was seven and England's pastoral heritage had become her own, she blossomed with

the following:

"The daffodils

bloom at Easter-time

And violets and primroses too.

They cover the wood

In a beautiful hood

Mauve and yellow and blue."

She was

destined to become a scholar, mainly because doing her very best and passing

examinations came easier to her than other childhood activities, like making

lots of friends and hanging out with the in-crowd. Otherwise, she lived in books

and a somewhat Blytonesque fantasy life in which she and the little sister dug

imaginary tunnels in imaginary woods and founded imaginary communities where

everyone ate what they pleased and went to boarding schools and made the

teachers look silly. She read everything she could get her hands on. She even

read a tome her father wrote, Fundamentals Of Psychology, or some fine thing,

hoping to find something about sex in it and plodding instead through

stultifying, Eisenckian disciplines and statistics and categorisings and

measurings.

He was what

we'd now call something of an emotionally absent man, her dad. A strange and

isolated sort of chap, he was passionate about world peace. Throughout Fleur's

early childhood he roamed around Europe speaking Esperanto with his Esperantist

chums, turning his attention to the conflicts of family life only in times of

dire emergency. He wrote just the once to his older daughter, a letter urging

her to cease bullying her sister on the grounds that it was not something

Captain Scott would have done. It was the best he could do, unaware, as he was,

that his hero had long since been eclipsed by Scarlet O'Hara in Fleur's scheme

of things.

She is a little

hazy about the bullying. She once threw a fork, yes, and sometimes she'd just

hit her. Well, she was irritating. Little sisters are. And when you're close,

you do things. Like project your own horrors and dreads on to the nearest

person. So, yes, she'd tell her spooky stories at night about ghosts and corpses

and graves and frighten the life out of her. And - she can't believe she did

this - she told her that her favourite doll, Pixie-Ann, had once been a little

girl and she wasn't now because her father took a gun and shot her dead. Which

was enough to put her off dolls and fathers and everything else.

She remembers

being 11 and going yet again to a new school. There were 13 of those, all told.

"Oh, we'll bring her out of herself," one headmistress promised, and Fleur

looked at her powdered face and her warts and had her doubts. So here she was

again, all alone in unfamiliar territory, where rather than hunch against a wall

for the duration of morning break, displaying herself as a wretched isolate for

the umpteenth time, she climbed to the top of a huge elm tree. It was, if you

like, an exercise in ambivalence. On the one hand she was escaping, on the other

she was courting attention. And, of course, they all gathered round. Who is that

daring, interesting girl? See how fearless she is, let us climb up and join her.

Some of them did just that, got stuck and had to be helped down. So it worked.

Up a tree she was a fascinating figure; down to earth a bit of a disappointment.

"Why do I write?" she says. "It's the same thing, isn't it? See me! Out on a

limb."

They took her

back to New Zealand after the war. The long journey home probably marked the end

and the culmination of her childhood. She and the little sister strung up

curtains in one of the ship's nether corridors and put on entertainment for the

other children. They wrote and performed a series of what they took to be

hilarious plays centred on a Mr Tommy Ato and his wife Poppette who ran a hat

shop. Tommy Ah-to. Tomato. She was 13. The series ran and ran. The children paid

up. England got further and further away till all she had left was an abiding

sense of loss and a bad case of homesickness.

Five years

later, she was sitting her finals at Wellington University, pregnant, married, a

shit-hot Latin scholar and fondly imagining she was grown up. She had seen her

husband across a crowded room and snapped him up for his physical beauty. He

looked like Gregory Peck only better, not as tall, alas, but divine. Exotic.

Half Polynesian. If she was obliged to live in Kiwi-land, she might as well have

the benefit. She fancied him "like mad". He was a romantic poet, published,

acclaimed, successful, all the things she wanted for herself. She wanted, yes,

to be him. Instead, she married him. It was a long time ago. "Look," she says,

"nobody took you seriously in the 50s unless you had a bloke or were married or

something. You couldn't get away from home, you couldn't shack up because that

was immoral. You weren't anyone. All the things Sylvia Plath suffered from."

So suddenly

there she was with a little house and a little mortgage, pushing a pram along

the street where Katherine Mansfield lived, desperately pretending to be grown

up. She had her poet, but he had a wife. There was no more dressing up and going

out having a good time. She was a suburban housewife, bored out of her mind. It

was Catch 22. You couldn't be an adult without a man and you couldn't be an

adult with a man. And when she thought about it properly she realised she didn't

really want to be him anyway. She wrote a poem at that time, called The Lover.

"Always he would inhabit an alien landscape," it went, so everybody thought it

was about the poet hubbie. But it wasn't. It was about herself, only in those

days you weren't allowed to have female personas in poems.

The marriage

lasted five years. Somewhere along the way she got caught in flagrante with

someone else, was as guilty as sin, had a second son, dwelt peaceably à trois

with the romantic poet's second wife for a spell, got a job and took off with

her baby under her arm.

She can't

believe she did this. How to put it? She was a child, 23 going on 12. She'd been

brought up to believe fair was fair; a cake for her, the identical cake for her

sister. There was nothing for it but to leave her first-born with his father. It

seemed fair. It was that bone-simple. She felt she had no more choice than if

her child had been snatched or had died. He would have the same parent, the same

home, the same bed, the same little tricycle, just a different mother.

"I just don't

recognise the girl who did this," she says, her voice dropping like a stone. "I

haven't a clue how her mind worked. This is me sitting here now, I've grown

cynical and I don't know who she is. Only in bits. Her past and her memories I

can see, but I don't recognise her in the mirror and I don't like looking back

on her. I don't admire her." And, more in sorrow than anger, she concludes that

she is jolly glad to have got away from someone so, so . . . so pathetic.

At 23, then,

with one small baby and a university lectureship to bless herself with, she

began to muddle through a facsimile of an independent life. The city of Dunedin,

where she worked, was "all lace curtains and Calvinistic disapproval," and a

divorced woman was ostracised in respectable company. The poems she wrote in

those days, she thinks now, seem to have been written by someone pretending to

be her. She had no idea how unhappy she was until one day she found herself

standing by the wall in her kitchen, waiting for the kettle to boil, with

unstoppable tears pouring down her face. The enormity of it all hit her like a

hammer. She had relinquished her child, and all the rationalisation in the world

wouldn't make it right. It was all wrong. Everything. Hopelessly wrong. Her love

affairs brought torment and obsession and guilt and going back to wives and

attempted suicides and God knows what-all. Romantic idylls of the kind you

imagine will continue in heaven have a tendency to be played out with married

men or those separated from you by great distances. They work rather as an

antidote to domestic enslavement but are invariably full of grief.

The citizens of

Dunedin, by this token, were probably right about young Fleur. Well- meaning

friends, perceiving her anguish, introduced her to various distractions, among

them a gentleman by the name of Barry Crump. "But don't marry him," they

counselled urgently, which was a mistake.

Among his many

distinctions, Mr Crump was incredibly famous in New Zealand. Searching for a

contemporary equivalent, Adcock thinks of Georgie Best. Or, better yet, Gazza.

He was a Crocodile Dundee sort of fellow who wrote adventure stories with titles

such as Hang On A Minute, Mate and A Good Keen Man. And, of course, he was an

absolute knock-out in bed. "Well, they are, aren't they?" she says, giggling

like a teenager. "Male chauvinist pigs always are. Think of Italians. Isn't it

perverse?"

Anyway, it

wasn't long before she displayed all the foresight and prudence of a lemming and

married him. It was, she says, the most horrifying thing she could think to do

to persuade herself out of more obsessive liaisons. He was soon routinely

smacking her in the mouth. "They do that, don't they?" she says. "Manly men.

They're fine in the pub telling jokes and stories, but in an argument they're

not so good at the old logic, so that's when they smack you across the mouth."

The marriage

lasted five months. By way of a divorce settlement, Mr Crump agreed to pay her

passage to England, less the £30 she'd already salted away for the purpose. And

she ran away. No. Correction. She ran towards.

It was

mid-winter when she arrived in London, as though the whole of England had been

kept on ice for her, waiting for her to come home. Sylvia Plath had taken her

life one week earlier. Nobody had heard of a poet called Fleur Adcock. She had a

six-year-old son, a couple of tea chests and some loose change, but the frost

was cruel and she was literally sparked by that. "When it's frosty," she says,

"I feel as though I've been taking some interesting drug."

Within months

she had a pensionable post as a librarian with the Civil Service in the Colonial

Office, which astoundingly respectable day-job sustained her for the next 15

years. That is to say it bought her a few hours of solitude each day to write

in.

She didn't need

anything else.

At 29, she knew

she would not marry again. Her record in this regard was not auspicious. "Five

years," she says, "then five months. What could I expect? Five weeks? Five

minutes?" For her, the difference between solitude, as in the need for

tranquillity with which to entertain her muse, and solitude, as in where is

everybody, were already fairly clear. Loneliness and solitude sometimes overlap,

but only sometimes. Sometimes you long for the phone to ring or someone to knock

on your door, but the feeling goes away if you allow it to.

The truth is,

she says, that she isn't really interested in relationships. Affairs, yes,

relationships, no. "People say you must work at a relationship. Well, I don't

want to work at it. I don't want to sit down and discuss it, I just want to have

it. Oh, God," she says, lapsing into giggles, "Speak to me! Let us set aside

time to hammer out our problems!

Let us have Quality Time

together!"

Clearly there

are no conventional rules nailed to her masthead. "You have to listen," she

says, speaking of her development as a poet, "to your own voice. Not your heart,

not your instincts, not any of that self-permissive psycho-babble stuff. No,

none of that. If it was just about instincts and bright ideas it wouldn't need

to be a voice. It's about words. You hear them, read them, then you write.

But mostly read. Read the bloody poems."

Her poems are

often born in the early morning or late at night when she is close enough to

sleep to have an open line to her unconscious thought processes. "The voice of

inspiration, or whatever corny title you choose to give it, comes from that

place. But it is also your own voice. And, on the whole, it speaks in colloquial

language and uses proper grammar and syntax." And, not for the first or the last

time, she insists, "There's nothing airy-fairy about being a poet."

"Art," she

declares, not at all portentously, "is whatever you choose to frame." This is so

neat it makes me laugh, but she is entirely earnest. She explains that she was

judging something or other, a poetry competition, and found herself in an

argument with Antonia Byatt. There was a poem she particularly liked; a verse, a

tiny, tiny thing that touched her. What's so wonderful about it, Byatt wanted to

know; any self-respecting novelist has this kind of thing on every page. Well,

yes, replied Adcock, but this has got white space around it. It's separate and

you look at it in isolation and not as part of a 200 page narrative, so it

fulfils another function.

It's a poem.

Lately, she has

consciously abandoned her muse, which is odd considering she has just written a

new poem exploring the rift. Forty years spent skittering her small fingers

across progressively lighter keyboards has landed her with a nasty dose of RSI,

a notoriously depressing ailment. It prevents her from driving and mowing her

lawn and opening screw-top jars, but does not seem to have stopped her being up

to her elbows in a hefty work of prose. For the past several years she has been

drawn deeper and deeper through tunnels of her own genealogy, partly as a homage

to English history, partly as a love affair she is conducting with her

ancestors.

Goodness only

knows who'd be interested, she says, but it has been entirely enthralling to

sleuth her way around the country leafing out the branches of her family tree

with stark information from parish registers and graveyards and tombstones.

There have been few thrills in her life to equal that of personally, physically

wrenching undergrowth from a 17th-century grave and knowing that the bones of a

forebear are personally, physically there, just below the stone. Or of

discovering in an ancient register that a male ancestor had been buried on the

same day that his illegitimate daughter was christened. What happened? He was

married, the mother of the child was a widow. These things are easy to check.

Did someone kill him? Did the widow wait till he was dead before she outed her

shameful bundle? There is no end to the goings-on, the intrigue and coincidence.

It has her quite hooked, like a soap-opera.

"The thing

about one's ancestry," she says in the intense whisper she reserves for matters

of particularly compelling intimacy, "is it's really about sex. These people

made us. It's about sex and the way you want to touch people, like wanting to

pat your grandchildren on their heads. Ancestors and poetry and religion are the

same. All about wonder. Having a sense of wonder."

Fleur Adcock

has entitled her latest poem The Ex-Poet. I don't believe a word of it

POEMS

1960-2000, by Fleur Adcock, is published by Bloodaxe Books, priced £10.95.

Saturday 15 May 2010

Dragon Talk, by Fleur Adcock

Julian Stannard admires

beautiful crafting and laconic punchlines

Julian Stannard

Dragon Talk, by Fleur Adcock, 64pp,

Bloodaxe,

Poems

1960-2000

gathered Fleur Adcock's many discrete volumes into a hamper. There was a

calendrial neatness to the project. Adcock had made her name in the 20th century

and the 20th century was over. The final poem in the book, coming out of a

sequence generated by a residency in Kensington Gardens, was called "Goodbye".

The summer was over, the residency had come to its end – "Goodbye, summer.

Poetry goes to bed" – and the valedictory nature of the piece hinted at longer

silences: "What wanted to be said is said." When I interviewed Adcock for the

poetry journal

Thumbscrew,

she took up the idea: "I've just got less interested in writing poetry but

you're not allowed to say this; people are terribly shocked. What really grips

me – what I continue to compose – is the narrative of my family history."

Adcock can wear these two hats at the same time. Family history, which becomes a

form of self-examination, has long threaded itself into the poetry. "The Voyage

Out", from

The Scenic

Route (1974), described the arduous journey of her great-grandmother

from Ireland to New Zealand in 1874. In

Looking

Back (1997) Adcock shook off the dust of the Records Office to

create a vivid almanac of ancestors. The collection is part of the poet's wider

enquiry into geographical and cultural displacement. Born in New Zealand in

1934, Fleur and her sister came to England in 1939. Growing up in Britain during

the war inculcated a sense of Englishness, and the family's return to New

Zealand in 1947 was resisted by the fledgling poet. Adcock's unwillingness is

shown in this collection in "Signature", in which she drags her feet through the

heavy snow of that mythological winter: "I was thirteen, and sensible only /

intermittently" and "I didn't want to leave." She returned to London

definitively in 1963, a week after the suicide of Sylvia Plath.

Her

first volume since

Looking

Back,

Dragon Talk

reveals that Adcock's curtain call at the end of the millennium was actually the

beginning of a long sabbatical. The dissonances and symmetries of her migratory

history continue to be the source of her poetry. The title poem shows the poet

grappling with the vagaries of voice recognition software (Dragon is a brand),

and the intransigence of technology affords various gags:

I

wait for you to lash your tail

each

time I swear at you.

But

no: you listen meekly,

and

print "fucking moron".

If

earlier poems acknowledge forbears who took on the challenges of emigration, the

dedication here is to the poet's mother, who died in 2001. The wider narrative

of family history is pulled into intimate space as the poet retraces her

autobiography, including the relationship with her mother – "We'll learn to be

good friends for forty years, / most of them spent apart, vocal with letters."

"My First Twenty Years", which sits at the heart of the collection, rehearses

the early journeys and transitions – pre-literate years in New Zealand, the move

to England on the eve of war ("September 1939"), the post-war return to a New

Zealand of cream sponges, where, notwithstanding the aunts' best efforts to

fatten her up, the teenager holds on, as a matter of principle, to English

austerity ("Unrationed"):

Cream, butter, cheese:

New

Zealand's dairy industry set to –

and

failed. Fat legs were not my destiny.

In "Kuaotunu"

the infant child draws a face "which looks more like the world", and this

exercise in cartography prefigures poetry that has typically looked across the

globe ("No one can be in two places at once"). Place names and dates make a bid

for permanence as the poet carefully stitches these new poems to earlier pieces.

"Sidcup, 1950", "Tunbridge Wells Girls' Grammar" and "Sidcup Again" push against

poems from

The Incident Book;

(1986) poems about her mother make us go back to "The Chiffonier", which

anticipated her mother's death. "August 1945" takes us to Dublin, where the

landlady advises against wearing red, white and blue:

Even

so, when we went to the pictures –

The

Commandos Strike at Dawn

– and the camp guards

hoisted the swastika, we still couldn't quite

believe our ears when the audience cheered.

In

response to "The Video" (1997), in which an older sibling watches the birth of

her sister and then makes her "go back in", "Fast Forward" shows the poet

looking at photographs of her great-grandmother and great-granddaughter and

feeling an inter-generational rush of wings.

These

beautifully crafted poems are full of laconic punchlines. "At least we hadn't

had that problem" ends "Precautions", after telling us about an unmarried friend

who trekked from doctor to doctor in search of contraceptives "until she found

one / who slashed her hymen with surgical scissors".

Dragon Talk

affirms the fact that poetry is memory and the painful irony of this is revealed

in the poems about her mother. Method is replaced by forgetfulness in "Summer

Pudding", while "Lost" shows an elderly woman "prowling around the flat" looking

for her children: "Where can they be?" Basil Bunting claimed it was "easier to

die than to remember"; Adcock scores the sand to defy the waves.

Julian Stannard's next collection will be published by Salmon Poetry.