8-2-2004

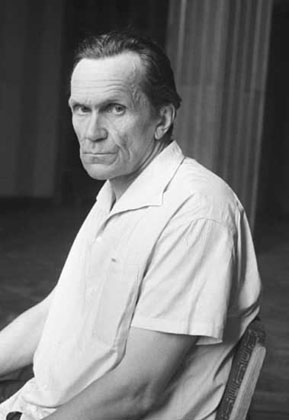

Varlam Tikhonovich Shalamov

Варлам Тихонович Шаламов

(1907–1982)

GULAG

Glavnoye

Upravleniye

LAGerej

|

Varlam

Shalamov

was a political prisoner who was arrested twice. His first arrest took place

while he was in his early twenties and was arrested several years later and

charged with "anti-Soviet Trotskyite activities." The first time, he was

sent to Solovki and then to Kolyma.

Kolyma

was one of the deadliest, if not the deadliest network of labor camps.

Conservative estimates calculate that 3 million people died in Kolyma. About

25-35 percent of the prisoners in Kolyma died each year.

Kolyma is located

in northeastern Siberia.

The environment is harsh year round. A prisoner's rhyme says:

Kolyma, Kolyma

Wonderful planet

Twelve months

winter,

the rest summer.

Winter temperatures

drop to -90 degrees f. Waters are ice 9 months of the year and soil is

frozen throughout. Insects, such as gadflies, appear in summer. Certain

types are especially big and can sting through animal hide.

In addition to the

environmental rigors of life in a place like Kolyma, the conditions of those

living in the camps made harder an already difficult life. Mining was the

sole operation in the Kolyma camps. Gold was discovered in 1910 and mining

in the area began in 1927, however, laborers were free and the operation was

worked on a very small scale. In the early 1930's mining began using forced

labor and continued until well into the 1950's. Kolyma was a region

comprised of about 120 full scale camps, 80 of which were dedicated to

mining. One of the most tragic points about Kolyma was that "almost without

exception" the prisoners held, many of whom ended up dead, were "entirely

innocent." |

|

|

|

|

LINKS:

Biography

and Bibliography

Poems in russian:

O

O

O

O

Athenian

Nights

Las noches

atenienses

On the

translation of his poems to french

Shalamov around the world

Vom Nachttisch geräumt

von

Arno Widmann

19.12.2003

Zwei Katzen und der tote

Bär

Warlam Schalamow wurde

1907 als Sohn eines russisch-orthodoxen Priesters geboren. 1929 kam er das erste

Mal ins Gefängnis. Er war dabei erwischt worden, wie er

"Lenins Testament",

jenen Brief, in dem der todkranke Lenin vor Stalin warnte, verteilte.

1931 wurde

Schalamow

aus der

Haft entlassen, ging zurück nach Moskau. 1937 wurde er wegen

"konterrevolutionärer Aktivitäten" erneut verhaftet und zu fünf Jahren

Lagerarbeit verurteilt. Er wurde nach Kolyma

geschickt, in jene kaum bevölkerte Zone im

Osten Sibiriens,

die das Zentrum des Gulagsystems war. Kaum entlassen, wurde er wieder

dorthin geschickt. Seit 1947 arbeitete er nicht mehr in Minen, sondern als

Arzthelfer.1953 kehrte er zurück nach Moskau. Seine Freundschaften mit

Nadeschda Mandelstam,

Pasternak

und

Solschenizyn

zerbrachen. Von letzterem sagte Schalamow, er habe keine

Lager gekannt und er habe sie überhaupt nicht verstanden. Schalamow schrieb

Gedichte, Essays, eine Autobiografie und einen Antiroman. Vor allem aber

arbeitete er von 1954 bis 1972 an seinen "Kolyma-Erzählungen". Teile davon

wurden klandestin verbreitet. Eine erste russische Ausgabe erschien 1978 in

London. Taub und blind starb Schalamow am 17. Januar 1982 in einer

psychiatrischen Klinik in Moskau. Auf deutsch erschienen kleine Auswahlbände.

Derzeit ist keiner lieferbar. Auf französisch liegen die "Recits

de la Kolyma"

jetzt vollständig auf 1515 Seiten vor.

Der Umfang schreckt ab. Wann

soll man 1500 Seiten lesen? Ich habe noch nicht mehr als 300 Seiten davon

gelesen. Aber es handelt sich um keinen Roman, auch um kein durch argumentiertes

Sachbuch, sondern um eine Sammlung von 146 Geschichten. Die meisten

berichten von Personen, stellen sie in einer konkreten Situation vor und

erzählen dann, wie sie dorthin kamen und was später mit ihnen geschah. Soweit

Schalamow das herausfinden konnte. Man kann die sechs Seiten über Tante Polia

lesen oder das Dutzend zur Schocktherapie, man kann auch die

Bärengeschichte lesen oder die über Caligula. Schalamow bietet noch in der

kleinsten Zelle seines Riesenwerkes die gesamte unverwechselbare DNA seiner

Erzählkunst. In der Bärengeschichte zum Beispiel reagieren zwei Katzen höchst

unterschiedlich auf die Erschießung eines Bären. Die eine verkriecht

sich, als wolle sie mit der Gewalt nichts zu tun haben, die andere wirft sich

auf den toten Riesen und leckt - wie triumphierend - sein Blut. Es ist immer

beides möglich. Niemand ist dazu gezwungen, so zu reagieren, wie er reagiert.

Schalamows Geschichten zeigen

den

Lageralltag.

Der Leser gewöhnt sich an ihn, wie die Insassen sich an

ihn gewöhnten. Das ist das Beunruhigendste an den Kolyma-Erzählungen. Schalamow

macht klar, wie selbstverständlich der Mensch nach einem kurzen Erschrecken das

Schreckliche nimmt. Da sagt ein Arzt zum Häftling, es müsse furchtbar

sein, in einer der Baracken zu leben. Man könne sich nicht einmal eine

Zigarette anzünden, schon blickten fünfzig Augenpaare neidisch, gierig auf

einen. Das, was den Reiz einer Zigarette ausmache, dieser Augenblick der Ruhe,

werde einem im Lager nicht gewährt. Man liest das und fragt sich und den Autor:

Ist der Arzt verrückt? Gibt es nichts Genaueres über den Archipel Gulag zu

sagen, als dass man sich dort nicht in Ruhe eine Zigarette anzünden kann? Es

gibt - so zeigt uns Schalamow - Momente, in denen der Wunsch nach einer in aller

Ruhe genossenen Zigarette alles andere auslöscht. Und es hat diesen Arzt

gegeben, der in diesem Augenblick alles, was ihm an Mitleid zur Verfügung

stand, in das Bedauern darüber goss, dass einem Häftling möglicherweise nicht

die Zigarette, wohl aber ihr Genuss vorenthalten bleiben musste. Fünf

Zeilen danach liest man, wie derselbe Arzt Patienten die Nägel von den

abgefrorenen Gliedern schneidet. Man bekommt eine Ahnung davon, dass es

Situationen gibt, die gerade die Betroffenen selbst nicht beim Namen nennen

wollen und können. Das Gespräch über Zigaretten mag die Gräuel der Lager

verschweigen, aber für die, die Bescheid wissen, ist es ein schreiendes

Schweigen.

Varlam Schalamows Kunst besteht

darin, seine Geschichten immer wieder bis an den Rand des Schreckens zu treiben.

Schalamow beschwört den Schrecken nicht. Er nennt ihn nicht beim Namen. Er

versucht nie, ihn einzufangen. Er kreist ihn ein. Manchmal kommt Schalamow von

ganz weit, aus Momenten, die denen des Glücks zum verwechseln ähnlich sehen,

dann wieder ist er dem Schrecken vom ersten Satz an hautnah.

|

ЗА РЕЧКУ АЯН-УРЯХ

Я поднял стакан за глухую дорогу,

За падающих в пути,

За тех, что идти по дороге не могут,

Но их заставляют идти.

За

их синеватые жесткие губы,

За одинаковость лиц,

За рваные, инеем крытые шубы,

За руки без рукавиц.

За

мерку воды - консервную банку,

Цынгу, что навязла в зубах.

За зубы будящих их всех спозаранку

Раскормленных серых собак.

За

солнце, что с неба глядит исподлобья

На то, что творится вокруг.

За снежные, белые эти надгробья -

Работу заботливых вьюг.

За

пайку сырого, липучего хлеба,

Проглоченного второпях,

За бледное, слишком высокое небо,

За речку Аян-Урях!

|

I raise my glass to a road in the

forest

To those who fall on their way

To those who can't drag themselves farther

But are forced to drag on.

To their bluish hard lips

To their identical faces

To their torn, frost-covered coats

To their hands without gloves

To the water they sip, from an old

tin can

To the scurvy which sticks to their teeth.

To the teeth of fattened gray dogs

Which awake them in the morning

To the sullen sun,

Which regards them without interest

To the snow-white tombstones,

The work of clever snowstorms

To the ration of raw, sticky bread

Swallowed quickly

To the pale, too high sky

To the Ayan-Yuryakh River!

Translated

by Anne Applebaum and Galya Vinogradova

Traduit

en français par Christiane Loré, le poème est inclus dans le recueil

Tout ou rien

(1993 :

156-157), ISBN

: 2-86432-183-1

Éditions Verdier -

1993, voir ici. |

|

Шоссе

Дорога

тянется от моря

Наверх по берегу реки,

И гнут хребты под нею горы,

Как под канатом бурлаки.

Они проходят друг за другом

В прозрачных северных ночах.

Они устали от натуги,

У них мозоли на плечах.

Они цепляются руками

За телеграфные столбы

И вытирают облаками

Свои нахмуренные лбы.

Через овраги, через ямы,

Через болота и леса

Шагают горы вверх и прямо

И тащат море в небеса.

|

LA CHAUSSÉE

La route s’étire de la

mer

Au-dessus de la rivière

;

Aux monts elle fait

ployer l’échine

Comme des haleurs sous

leur cordage.

Sur la nuit transparente

du Nord

Les monts se profilent

tour à tour

Las de l’effort dont ils

portent

Les stigmates sur

l’épaule.

Cramponnés comme ils le

peuvent

Aux poteaux

télégraphiques,

Ils épongent sur les

nuées

Leur front harassé.

Par-delà ravines et

abîmes

Par-delà marais et

forêts

S’élèvent droites les

cimes

Tirant la mer jusqu’aux

étoiles.

(*) |

|

Камея

На склоне гор, на

склоне лет

Я выбил в камне твой портрет.

Кирка и обух топора

Надёжней хрупкого пера.

В страну морозов и мужчин

И преждевременных морщин

Я вызвал женские черты

Со всем отчаяньем тщеты.

Скалу с твоею головой

Я вправил в перстень снеговой,

И, чтоб не мучила тоска,

Я спрятал перстень в облака. |

Camée

Au déclin de l’âge, sur la

pente des monts

J’ai taillé ton portrait dans

le roc.

Plus sûrs que la plume

gracile,

La hache, le pic et la cognée.

Au pays du gel et des mâles

Et des visages tôt burinés,

Sans espoir, simple vanité,

Les traits d’une femme j’ai

évoqués.

Lors, dans l’anneau de neige

J’ai serti ton profil de

pierre.

Puis redoutant l’obsédant

regret

J’ai celé l’anneau dans le

ciel.

(*) |

|

Я жив не единым хлебом,

А утром, на холодке,

Кусочек сухого неба

Размачиваю в реке...

|

Je ne vis pas seulement de pain

Dans le froid noir du petit matin

J’ai trempé dans la rivière

Un morceau de ciel clair…

|

|

Чем ты мучишь? Чем пугаешь?

Как ты смеешь предо мной

Хохотать, почти нагая,

Озаренная луной?

Ты как правда — в обнаженье

Останавливаешь кровь.

Мне мучительны движенья

И мучительна любовь...

|

Pourquoi me tourmenter, m’affoler ?

Comment oses-tu,

À demi nue,

Rire aux éclats sous la lune ?

Comme la vérité, toute nue

Tu me figes le sang.

Tout mouvement m’est tourment

Et tourment m’est amour…

(*) |

|

Всё

те же снега Аввакумова века.

Всё та же раскольничья злая тайга,

Где днём и с огнём не найдёшь человека,

Не то чтобы друга, а даже врага.

|

Toujours la même neige de l’époque d’Avvakum

Toujours la même taïga mauvaise et

schismatique,

Pas un feu, pas un lieu, ni âme qui

vive

Pas un ami, pas un ennemi.

(*) |

|

Лунная ночь

Вода сверкает как стеклярус,

Гремит, качается, и вот –

Как нож, втыкают в небо парус,

И лодка по морю плывёт.

Нам не узнать при лунном свете,

Где небеса и где вода.

Куда закидывают сети,

Куда заводят невода.

Стекают с пальцев капли ртути.

И звёзды, будто поплавки,

Ныряют средь вечерней мути

За полсажени от руки.

Я в море лодкой обозначу

Светящуюся борозду

И вместо рыбы наудачу

Из моря вытащу звезду.

1958

|

NUIT DE LUNE

L’eau scintille comme du jadis, gronde

Et ondule… quand sur le ciel

Une voile plante son couteau :

Le rafiot prend la mer.

Qui dira, sous la lune,

Où est l’eau, où est le ciel,

Où est jetée la senne,

Où l’on tire les filets.

Les doigts dégouttent de mercure,

Et les étoiles, comme des bouchons

Plongent à demi sagène *

Dans la vase obscure.

Je tracerai un lumineux sillon

Sur la mer avec le rafiot ;

À tâtons, en guise de poissons,

Je tirerai une étoile de l’eau.

* Ancienne mesure équivalant à 2,13

mètres. N.D.T.

(*) |

|

Сыплет снег и днем и ночью.

Это, верно, строгий бог

Старых рукописей клочья

Выметает за порог.

Все, в чем он разочарован -

Ворох песен и стихов,-

Увлечен работой новой,

Он сметает с облаков.

|

Il neige jour et nuit

Sûrement, c’est un dieu sévère,

Qui balaie de son seuil

Ces vieux bouts de manuscrits.

En somme, tout ce qui l’a déçu,

Lambeaux de chants et de vers,

Attelé à de nouvelles tâches

Il le chasse du haut des nues.

(*) |

|

От

солнца рукою глаза затеня,

Седые поэты читают меня.

Ну что же – теперь отступать

невозмсжнс.

Я строки, как струны, настроил

тревожно.

И тонут в лирическом грозном потоке,

И тянут на дно эти темные строки…

И кажется, не было сердцу милей

Сожженных моих кораблей…

|

De la main, se gardant du soleil

Les poètes aux tempes grises me

lisent,

Que faire ? Trop tard pour me

dérober :

Sur ma lire angoissée, les vers sont

accordés.

Déjà, dans le flot menaçant. ils

sombrent

Mes sombres vers et me tirent au

fonds…

Pourtant rien, paraît-il, me fut plus

cher

Que mes vaisseaux brûlés…

(*) |

TOAST EN L’HONNEUR DE L’AIAN URIAH *

Je porte un toast – au layon,

À ceux qui tombent en chemin

À ceux qui sont épuisés

Que l’on force à se traîner.

Aux lèvres bleuies et crevassées

À l’identité des visages

Aux pelisses trouées et givrées,

Aux moufles qu’ils n’ont pas.

Au quart d’eau, à la boîte de conserve

Au scorbut pris dans leurs dents

Aux dents de chiens gras et nourris

Qui les houspillent dès le matin.

Au soleil qui du ciel louche

Sur ce qui se passe à l’entour.

Aux blanches sépultures de neige,

Don charitable de la tourmente.

À la ration de pain gluant

Engloutie en toute hâte

Au ciel pâlot, et trop haut,

À la rivière Aian–Uriah !

(*)

L’

Aian–Uriah est un affluent de la Kolyma au bord duquel étaient exploitées les

mines d’or du camp de la mort d’Arkagala,au pôle du froid de l’Extrême-Orient

russe. Chalamov y demeura plus d’un an. N.D.T.

(*)

Traductions en

français par Christiane Loré, du recueil

Varlam Chalamov, Tout ou rien, ISBN

: 2-86432-183-1

Éditions Verdier,

1993.

Fri., April 15, 2005 Nisan 6, 5765

"Sipurei Kolyma" ("Kolyma Tales") by Varlam Shalamov,

translated from the Russian by Roi Chen, Yedioth Ahronoth, Hemed Books, 269

pages, NIS 84 [English edition: "Kolyma Tales," translated by John Glad,

Penguin, 528 pages].

Fragments from the gulag

By Raviel Netz

When Russian intellectuals get to talking about books written

about the horrors of Stalinism, the discussion generally begins by tearing apart

Aleksander Solzhenitsyn: "Highly overrated ..." "Not a great writer ..." "Very

superficial ..." That will get some people jumping up to defend him, and

everyone will agree: "Of course you have to hand it to him for his courage in

writing `The Gulag Archipelago.'" A minute later, someone will exclaim, and the

crowd will parrot after him: "Now Shalamov is a real writer. Maybe one of the

greatest writers of the 20th century!"

Shalamov was a "one-subject author." He wrote about the gulag, and more

specifically, the gulag of Kolyma. He was there himself, and the truth radiates

from his stories. But Shalamov is a spinner of tales, not just an eyewitness.

From an artistic standpoint, he keeps company with Russia's finest literary

lights. Hence the importance of reading him twice: once to learn the truth about

Kolyma (a truth than only fiction can convey) and again, to expose oneself to

another pinnacle of Russian writing. Apart from the masterpieces of the 19th

century, the 20th century has also produced some gems.

The publication of this Hebrew edition of Shalamov is thus an important and

welcome literary event, for which the publisher deserves kudos. Likewise, we owe

the translator, Roi Chen, a special note of thanks and appreciation. In the

past, Chen has translated Daniel Kharms, another brilliant 20th century Russian

author.

Varlam Shalamov, born in 1907, was sent to the gulag in 1929 and

only gained his full release in 1953. Over the next 20 years, when he was old

enough to have been reaping the benefits of a flourishing literary career, he

lived the impoverished life of an ex-prisoner on the margins of Soviet society.

During that time, he wrote more than 100 short stories, enough to fill two thick

volumes. The stories are organized in sections, and Part I is the section that

has been translated into Hebrew.

Shalamov's tales are essentially self-contained: One can read them in any order

almost without losing anything. For example, the story "Berries," which begins

with the narrator sprawled on the snow, refusing to continue the night march

back to the camp dragging a heavy log for firewood. Accused of feigning illness,

he is beaten. He curses the guards, and one of them promises to shoot him dead

one day. The next day, the narrator is with a fellow inmate, Rybakov, gathering

berries for the camp. This was a particularly desirable job - not very taxing

physically, and one could gather a bit "on the side," for those willing to take

a risk. The nature descriptions here are typical Shalamov - brief and sparing

but also lyrical.

As always in the gulag, any place where the prisoners happened to be was

immediately divided into "permissible" and "forbidden" zones. In this case, the

guard - the same man who threatened the narrator the night before - has used

bundles of grass to mark the boundaries. A tempting bunch of berries lies just

beyond. Rybakov steps over the line and is shot to death by the guard. On the

way back to the camp, he snarls at the narrator: "It's you I wanted. But you

didn't give me the chance, you piece of filth!" That is how the story ends.

Is this a "happy end"? It's hard to see it any other way. Reading "Kolyma

Tales," the will to survive comes across very strongly. Every tale is measured

by the narrator's success in staying alive. Only later the irony seeps in. Does

the narrator bear any kind of moral responsibility? Did he foresee what was

about to happen and in some sense allow Rybakov to die? At the end, he adds a

comment about how he got his hands on Rybakov's crate of berries, hoping it

might earn him an extra crust of bread. But what kind of morality exists in this

world that Shalamov describes? It is a world where people are executed on a

whim, where a guard sets a trap, and when the wrong person falls into it, he

goes ahead and pulls the trigger anyway. The story does not supply an answer to

any of these dilemmas.

Arbitrary world

In tales like "Berries," Shalamov avoids the "heroic" genre, in which the

protagonist is portrayed as a hero who overcomes terrifying ordeals. But neither

does he fall into the trap of pathos, depicting the narrator as an innocent

victim. Invoking heroism or pathos, with their conventional literary and ethical

codes, would be an affirmation of normalcy amid the horror. To describe the

hellishness of Kolyma without compromise, Shalamov invents a literary form free

of all convention, and therein lies his greatness.

It is tempting to compare Shalamov to the Polish-Jewish writer Ida Fink. The

short story is essential to the oeuvre of both authors, and the question is why.

We are touching on something very fundamental here. The essence of a short story

lies not so much in its length but in its not being a novel. Novels are based on

a logical plot in which the protagonist achieves - or more often, fails to

achieve - his heart's desire while engaged in a battle with those around him.

The outcome of the story is a product of cause and effect: The protagonist has

chosen to do such and such, and therefore such and such happens. The novel is

teleological. It belongs to an ordered universe. The short story, at its best,

frees the author from teleology.

To put it simply, Shalamov, like Ida Fink, describes a world where there are no

causal relationships, where one thing does not lead to another. The core event

in Western literature - the death of God - becomes the product of arbitrary,

unpredictable circumstances that have no collective significance. That is

precisely where Solzhenitsyn went wrong. He chose to write novels about the

gulag, i.e., he tried to create protagonists whose experience was coherent and

causal. The outcome was a kind of socialist realism behind barbed wire.

Shalamov's use of the short story, the fragment, fits so much more for the

fragmentary, arbitrary world of the gulag.

Comparing Shalamov and Fink presupposes a comparison between the gulag and

Auschwitz - one that begs to be made, but is also a source of discomfort for

Israelis who have been raised on the "uniqueness" of the Holocaust, and for

adherents of the same politically enlightened views shared by the leftist

intellectuals of Western Europe, who justified the atrocities in Stalinist and

Soviet Russia. Kolyma, the setting of Shalamov's stories, is the perfect place

for probing these issues - a remote province that was beyond the reach of any

railway, deep in northern Siberia, one of the coldest and most godforsaken

places on the planet.

Kolyma was cursed with large gold mines. The Soviet regime sent out millions of

human beings to extract the gold, even if they had to die for it. In Kolyma,

more than anywhere else, the gulag camps were death camps. The brutal slave

labor in subfreezing temperatures was a source of torment no less horrible than

any other saga of human suffering. Some people like to pounce on slight

differences. They will see a veneer of economic rationality in the exploitation

at Kolyma (although Nazi slave labor made even more economic sense), or argue

that Kolyma laborers were not selected by race (although Stalinist reality was

such that being a member of the middle class - defined by who your relatives

were - was often a death sentence in itself). Morally, though, there was no real

difference.

At the same time, the experience of the gulag victims was distinctive in a

certain respect. As Soviet citizens, they never believed for a moment that they

were looking at a rational, predictable system. They were familiar with the

corruption and the chaos that characterized Soviet life as a whole. They assumed

that luck, and finding someone with influence, might offer protection and some

chance of survival, however slight. In this sense, there was something "Russian"

about the gulag, which helped to mitigate some of the horror.

Card games and duels

The renowned cultural theorist Yuri Lotman has written about the importance of

arbitrariness in the Russian imagination - the way that wealth and poverty, as

well as violent death, tend to be a product of unforeseen circumstances. Think

of how symbolic card games and duels are in Russian culture. In Shalamov's

stories, the characters do play cards, but in some respect, every one of them

features a duel in which the bullet misses the narrator by a hair's breadth. In

their arbitrariness, Shalamov's "fragments" are thus Russian to the core. His

writing may go against the literary principle of the novel, but it is still a

continuation - gloomy and chaotic - of a tradition that goes back to Mikhail

Lermontov's "The Fatalist" and Pushkin's "The Queen of Spades."

Shalamov's style is lean and devoid of frills, but it approaches the sublime. He

succeeds in capturing the crude and dissonant language of life in the gulag

without losing the clarity of artistic, Tolstoyian prose. Roi Chen manages to

preserve all this in his translation, for which he deserves the highest praise.

The author teaches history of science at Stanford University. He

is also a poet.