4-12-2004

"Blanco

sobre negro",

de Ruben Gallego

"Черным

по белому",

Рубен Давид Гонсалес Гальего

2006 - English translation

WHITE ON

BLACK - see it

here

Sat., June 05, 2004 Sivan 16, 5764

Written with one finger

By

Dr. Anna Isakova, a journalist and writer.

Gallego sees his writing as a

protest and as an instrument designed to help those who are trying to survive in

this black-and-white world

“White on Black" by Ruben David Gonzales

Gallego, St. Petersburg: Limbus Press, 220 pages [in Russian]

|

The Booker-Open Russia Literary Prize

travelled to Madrid last year. Ruben David Gonzales Gallego, a Spaniard who

writes in Russian, received the award for his autobiography, "White on Black."

As a child stricken with cerebral palsy (CP), he was in effect given a death

sentence: hospitalization in Soviet treatment facilities. But he was a survivor

and he triumphed in the battle for life. A number of members of the jury

selecting the winner of the prize - a highly prestigious Russian award modelled

after Britain's Booker Prize, which provides the laureate with $15,000 and

assistance in sales promotion - felt that, in this case, the prize was a medal

of valour, rather than a literary award. It would have been unthinkable not to

have granted it to Gallego.

The chief juror for the 2003 award, Yakov Gordin, explained

why "White on Black" was chosen: "People today need a `courage vaccine.' We tend

toward panic and catastrophic black moods. Gonzales Gallego's book, besides

being a very respectable literary work, is a remarkable lesson in courage.

|

|

|

|

As

one of the jurors for this award put it, this book belongs in the same category

as Nikolai Ostrovsky's `How the Steel Was Tempered,' which describes the process

of an individual's death and which was also written by a handicapped person.

Ruben's book is the story of an individual's resurrection with the help of a

mighty intellectual effort. It represents the triumph of spirit over matter."

Ruben Gallego's full story is not recounted in his book and

will apparently never be told. Meanwhile, the Russian Internet is packed with

biographical information relating to him. There are those who have written that

he is the son of Aurora, rebellious daughter of Ignacio Gallego, a former leader

of the Spanish Communist Party. According to some accounts, Aurora studied in

Paris, acquired the reputation of being a radical leftist and thus "betrayed"

the communist ideal. Her father sent her in the 1960s to the Soviet Union so

that her ideology could be "corrected." She lived in Moscow for eight years -

some say as "collateral in the hands of the Kremlin." There she met and married

a student from Venezuela, the son of a racially mixed family of Indians and

Chinos (Chinese of Latin American origin).

The leader of the Spanish Communist Party did not like this

racial blend and opposed the marriage. Aurora stuck to her guns and, in 1968,

she gave birth to twins. Immediately after the delivery, she was informed that

one of the infants was dead and that the other had CP. Eight days later, the

mother was told that the second twin had also died. In truth, however, the

infant was transferred to an outside facility. No one knows who gave the order

for the transfer - whether it was the Kremlin or the grandfather. An even deeper

mystery is concealed in the fact that the infant retained his full name.

Secrets and mysteries

The child was placed in several treatment facilities, for want

of a better word. He was simply neglected, undergoing a seemingly endless series

of painful treatments, with his future already predetermined. In the Soviet

Union, it was customary to keep severely disabled children in closed

institutions until the age of 18, whereupon they were placed in closed

facilities for the chronically ill, where they died soon after placement due to

neglect.

Gallego was saved from this fate by a woman whose name has

remained a mystery. No one knows who she was or whom she represented. The author

does not solve the mystery in his book or in his many press interviews. After

having been saved from life in a treatment facility, he attended college, got

married twice and became the father of two daughters. By pure accident, he

arrived in Prague, where he met his mother (again, under mysterious

circumstances), and subsequently took up residence with her in Madrid. Today

Gallego's health is shaky; however, he says that he has no desire to visit

Russia, even if he would be up to to such a trip.

The book does not relate to the secrets and mysteries of this

bizarre tale. Instead, it starts on one cold winter night in a Russian treatment

facility. A little handicapped boy has to urinate. It would make no sense to

summon for help, because no one would respond. The child already knows that,

given his inability to use either his arms or legs, he must be a hero or die.

The young boy decides to be a hero. He pushes his body to the edge of the bed

and falls to the floor. He feels pain, and yet crawls in the direction of the

door, opens it with his head and continues to crawl along the frozen corridor.

He spends almost the entire night crawling to the bathroom and back. Since he

cannot manage to return to his bed, he pulls the blanket off the bed with his

teeth and remains on the floor until morning.

In the morning, he is taken to school. He is a good student.

He is a hero. This hero lives among other similar heroic figures. The disabled

children are survivors and even manage to display gentleness, friendship and

love toward one another.

"White on Black" is a relatively short book, written in short,

simple sentences. The author typed out the manuscript with only one finger. He

relates that this was painful, and it would be safe to assume that his physical

condition encouraged him to be laconic. In an interview with Radio Free

Europe/Radio Liberty, which today broadcasts from Prague (passages from

Gallego's book were first heard on that radio station's literary program), the

2003 Booker - Open Russia Literary Prize laureate confesses that he learned from

Gertrude Stein how to divide up sentences into small segments, thereby forcing

readers to stop and think after each period. This technique does not always work

in his book: Gallego does not attain the plastic sophistication of Stein's

balanced sentences, and sometimes passages in his book sound much like

telegrams.

One can perhaps consider "White on Black" an antithesis to

William Golding's "Lord of the Flies," although it is unclear whether Gallego

ever read it. In his book, Gallego is continually reading books, although the

only one that is specifically mentioned is "How the Steel Was Tempered." The

body (in both the anatomical and textual senses), and the missing parts of that

body, occupy such a prominent place in Gallego's book that one can sense a

striking similarity to Jean Genet's writing.

The book has no plot. In episode after episode, we learn how

handicapped infants, young children, adolescents and adults manage to survive in

conditions that rule out the possibility of survival. The infants learn how not

to die, the children learn how to help one another, the adolescents learn

mathematics although they are clearly aware that their end is near. The adults

learn nothing. They are dead.

Here is a passage from one of the book's final chapters:

"Institution. A home for the aged. The last asylum of my life.

End. Dead end. I am writing down irregular English verbs in my notebook. Along

the corridor attendants are carrying a cot with a dead person in it. I am

writing down irregular English verbs in my notebook. Handicapped people of

various ages are organizing a Komsomol rally. In the auditorium, the

institution's director delivered a speech in honor of the anniversary of the

October Revolution. I am writing down irregular English verbs in my notebook.

One grandfather, a former prisoner, got drunk and smashed in the head of his

roommate with a pair of crutches. A grandmother, a distinguished Labor heroine,

went into a wardrobe cabinet and hanged herself. A woman in a wheelchair gobbled

down a handful of sleeping pills in order to take permanent leave of this

irregular world. I am writing down irregular English verbs in my notebook."

Needless to say, Gallego does not consider his writing a

literary product; instead, he sees it as a protest and as an instrument designed

to help those who are trying to survive in this black-and-white world, in the

demarcation line that separates daylight from eternal darkness. After you have

read "White on Black," the problems of ordinary people lose all importance and,

in the final analysis, it is possible to see it as a decidedly optimistic book.

Jeudi, le 19

Juin 2003

Des

pieds et des mains

Avec un souffle digne des «Récits de

Kolyma», l'histoire effarante d'un handicapé dans l'URSS de Brejnev.

Par Jean-Pierre THIBAUDAT

RUBEN GONZALEZ GALLEGO

Blanc sur noir

Traduit du russe par Aurora Gallego et

Joëlle Roche-Parfenov . Actes Sud/Sollin, 208 pp. 18 €

|

Ça commence comme ça : « Je suis un héros. Il est facile

d'être un héros. Quand tu n'as ni bras ni jambes - tu es un héros ou tu es mort.

Quand tu n’as pas de parents - compte sur tes bras et tes jambes. Et tâche

d’être un héros. Si tu n’as ni bras ni jambes et qu’en plus tu t’es arrangé pour

venir au monde orphelin - c’est gagné. Tu es condamné à être un héros jusqu’à la

fin de tes jours. Ou à crever. Je suis un héros. Je n’ai tout simplement pas le

choix. » Fin du premier paragraphe. Deux cents pages, du même tonneau.

|

|

|

|

D’emblée, le souffle d’une voix qui vient de loin, de trop loin

pour céder aux complaisances du pathétique, du larmoyant ou du sordide. Le

souffle d’une vie scandée en une quarantaine de ponctuations, comme une

confession déterminée, débarrassée de ses scories pour avoir été longtemps

retenue et ruminée. D’emblée, une férocité traversée d’éclats de rire

effrayants, autrement dit, un manuel de survie pour tous les entravés, les mal

nés, les lourdement handicapés. D’emblée, une œuvre qui cisaille les sentiers

habituels de la narration. Un choc qui nous vient de Russie. Transporté que l’on

est par la fièvre maîtrisée de ces pages signées Ruben Gonzalez Gallego, comment

ne pas songer aux Récits de Kolyma de Varlam Chalamov ? Ce dernier a

passé prés de vingt ans au goulag à une époque où Ruben, fils objectif de

Chalamov, n’était pas encore né. C’est dans les orphelinats, des centres pour

handicapés que Ruben Gallego a passé sa jeunesse soviétique. Un monde où l’on

est forcément coupable, comme au goulag. Coupable d’être né handicapé. Passé 18

ans, les handicapés soviétiques incapables d’exercer un « métier utile »

étaient transférés dans un asile de vieux. En russe ça veut dire mouroir. Les

jeunes copains handicapés de Ruben y sont morts. Lui s’en est sorti. C’est un

héros.

« À neuf ans, je compris que je ne pourrais jamais marcher.

Ce fut très triste. Adieu pays lointains, étoiles et autres joies de la vie. Il

ne restait que la mort.. Lente et inutile ». Ces mots écrits en russe par

son fils, Aurora Gallego a aidé à les rendre en français. Fille du secrétaire du

Parti communiste espagnol clandestin réfugié à Moscou, Aurora vivait à Moscou

sous Brejnev avec un militant du PC vénézuélien. Enceinte de jumeaux, on lui

accorde le privilège d’accoucher à la clinique du Kremlin. Deux enfants naissent

en septembre 1968. Le premier meurt. Le second, c’est Ruben. Lourdement

handicapé des bras, des jambes, de la tête. Sa mère le suit quelques mois

d’institution en institution, puis un jour, on lui annonce que son fils est

mort. Ruben, seul, pousuit sa vie d’handicapé désormais orphelin dans des

établissements où les enseignants, les infirmiers mentent. Tout le monde ment

aux « débiles » Sauf les niania. Nounous, gardiennes, veilleuses

de la vie. Celles qui disent à Ruben en lui donnant un bonbon : » pauvre

gosse, il vaudrait mieux que tu meures le plus vite possible, tu ne souffrirais

plus et nous non plus ».

Ruben se souvient. La vie était simple: ramper, brailler,

manger. Ses meilleurs souvenirs sont liés à la nourriture. Sa petite madeleine :

une nuit dans un hôpital, une infirmière en « robe élégante » se penche sur lui,

murmure : « ouvre la bouche et ferme les yeux ». elle lui glisse un

chocolat, la tête lui tourne, « je suis bien, je suis heureux ». l’URSS

est un paradis. Les enseignants décrivent aux jeunes handicapés le cauchemar

qu’est la vie dans les pays capitalistes, à commencer par l’Amérique. Un pays

peuplé d’ennemis qui boivent le sang de la classe ouvrière et où les ouvriers

affamés font la queue devant l’ambassade de l’Union Soviétique pour changer de

nationalité. « C’est ce qu’on nous apprenant, nous y croyons. » Le pompon

c’est les invalides américains. « On les tue là-bas. Si dans une famille naît

un handicapé, le médecin fait à l’enfant une piqûre mortelle », disent les

enseignants. C’est pas comme en Russie soviétique où on les « nourrit

gratuitement ». Ruben a 9 ans quand il entend ça. « Je veux une

piqûre, une piqûre mortelle. Je veux aller en Amérique ».

Les années passent. Ruben a peur de finir à l’asile des fous ou

à l’asile des vieux. Ceux qui si tiennent à carreaux évitent d’aller chez les

fous où l’on conduit d’autorité ceux qui se plaignent, de la nourriture, par

exemple. Mais à l’asile des vieux, « tous ceux qui ne pouvaient pas marcher y

atterrissaient ». Même un bon élève comme Ruben. Petit-fils d’un communiste

haut placé (ce qu’il ignorait mais ce qui était sans doute marqué dans son

dossier) on lui accorde une faveur : on le conduit à l’asile des vieux dans son

fauteuil roulant. Or « ceux qui quittaient le foyer n’avaient pas le droit

d’avoir leur fauteuil, On les emmenait chez les vieux sans leur fauteuil, on les

posait sur un lit et on les laissait ». L’asile des vieux, c’est le « cul

de sac » final. Des pépés ivres se castagnent à coups de béquille, une

grand-mère médaillée du travail se pend dans un placard, les handicapés crèvent

dans les deux mois qui suivent leur arrivée. Ruben résiste, « pour ne pas

devenir fou », il copie dans un cahier les verbes irréguliers anglais. Et

aujourd’hui, il décrit avec saisissement ce « lieu effroyable » où seuls

les anciens zek (prisonniers du goulag) trouvent leurs repères. « Ils

se sentent chez eux à l’asile ». : c’est comme dans les camps.

L’auteur avance ainsi, par brèves séquences concentrées, lestées

de vie, autour d’un fait, d’une personne. Non de la « prose documentaire »

mais de la « prose vécue » pour reprendre des catégories propres à

Chalamov lequel, dans ses récits, disait « fixer l’exception dans

l’exceptionnel ». Ce que fait, à sa manière, bordée d’un lyrisme

sous-jacent, Ruben Gonzales Gallego. Dans l’asile de vieux, une jeune femme,

Katia, qui vient rendre visite á son père, s’attarde au prés de Ruben. à la

faveur de la perestroïka, elle réussira à le faire sortir en 1990. Il fonde une

association d’aide aux handicapés. Ce qui lui vaudra d’être invité aux

États-Unis. Là-bas, on lui prête un fauteuil roulant dernier cri. Pour la

première fois de sa vie, assis dans son fauteuil, Ruben Gallego traverse seul

une rue. Il pleure quand il doit dire adieu à cet engin pour revenir en Russie.

Un jour, des amis de Rostov-sur-le-Don l’emmènent à Madrid

chercher les traces de sa famille. Rien. Mais quelqu’un lui parle d’une femme

qui travaille à Prague, à radio Liberty, une certaine Aurora Gallego. Sur la

route du retour en Russie, Ruben et ses amis font un crochet sur Prague. Le fils

retrouve sa mère qui ne savait pas que son fils était encore en vie. C’est après

ces retrouvailles qu’il a commencé à écrire ce livre en le tapant sur le

clavier d’un ordinateur, d’un doigt, l’un de ses deux doigts pas atrophiés,

l’index de sa main gauche. Sorti en décembre 2002 á Moscou, l’ouvrage a « donné

lieu à un débat sur l’enfance, le système socialiste, l’évacuation de tout ce

qui gênait le mythe de l’homme nouveau dans un pays où tout le monde devait être

heureux », écrit Aurora Gallego dans la postface. Ruben Gallego vit

aujourd’hui à Madrid avec sa mére et sa demi-sœur. Avec l’index de la main

gauche, il travaille à un nouveau livre.

LINKS:

Directory

Article and interview by Miguel Angel Mellado

Excerpts from the book

Directory in Russian

THE ST. PETERSBURG TIMES

#927, Thursday,

December 11, 2003

booker winner beats the odds

By Galina Stolyarova

A Russian resident of Madrid was

named winner of the 2003 Open Russia Booker Prize last week for his novel,

"White on Black," published by St. Petersburg-based Limbus Press.

Paralyzed from birth, Ruben David

Gonzales Gallego did not attend the ceremony last Thursday, but the $15,000

award guarantees him the publicity of Russia's most prestigious literary honor.

Grandson of a general secretary of the Spanish Communist Party, Gallego grew up

in a series of Soviet homes for the permanently disabled - a harrowing

experience scrupulously detailed in the pages of his novel.

St. Petersburg poet and critic

Tatyana Voltskaya called Gonzales Gallego's victory a rare combination of talent

and remarkable life experience.

"Of course, someone might be

tempted to say that the writer won primarily owing to exploitation of his

sorrowful childhood and his being disabled," she said.

"But 'White on Black' is a piece

of genuine art, when the writer is not playing with words for the sake of form

or experiment."

The award ceremony came two months

after the shortlist of six finalists was announced. Founded in 1991 by the

prestigious British Booker Prize, the Russian Booker was hailed as the first

independent literary award since 1917. Worldwide attention zeroed in on the

winners, who have included Bulat Okudzhava, Ludmila Ulitskaya and, last year,

Oleg Pavlov.

However, with the proliferation of

literary prizes, many readers now look elsewhere for Russia's literary

avant-garde. In 1997, the prize lost its British backing when it was taken over

by a branch of the Smirnoff vodka company. In 2002, it was turned over to the

Open Russia Foundation, a fund of Yukos shareholders headed by jailed oligarch

Mikhail Khodorkovsky.

Of the six novels that made it to

this year's shortlist, only two - Gonzales Gallego's novel and Leonid

Yuzefovich's "Kazaroza" - initially appeared as books. The others - Yelena

Chizhova's "Monastery," Afanasy Mamedov's "Frau Shram," Leonid Zorin's "Jupiter"

and Natalia Galkina's "Villa Renault" - were printed in journals, a vestige of

the Soviet literary industry that has not fared well since publishing took off

in the 1990s.

Established in St. Petersburg 15

years ago, Limbus Press became Russia's first private publishing house after the

downfall of the Soviet Union.

Its general director, Konstantin

Tublin, called the win of "White on Black" deserved and commendable.

"In my opinion, the jury's choice

was incredibly easy this year," Tublin said. "In fact the real choice for the

Booker was to either support Gonzales Gallego or just destroy itself. It is

encouraging to see that the prize has chosen to live on."

Some of Gonzales Gallego's rivals

were so impressed with his work that they have spoken publicly of the writer's

talent. Yulia Belomlinskaya, representing St. Petersburg's Amphora Publishing

House and who was nominated for her novel "Poor Girl," withdrew her name from

the competition during the short-listing process when she heard that Gallego's

book was in contention.

"She told the jurors that she

believes all the laurels of the contest should go to Gallego, as his novel is

extraordinary," said Amphora's chief editor Vadim Nazarov.

"She felt it would be dishonest of

her to compete with someone whose novel she admires."

At a press conference before the

winner was announced, critic Igor Shaitanov, who heads the Booker Prize jury,

argued that the number of nominees drawn from literary journals is proof that

they still cater to the public's taste.

But the question of what exactly

the public wants to read seems far from settled. Given a choice of topics, all

the finalists who attended the Booker Prize ceremony - Chizhova, Yuzefovich and

Mamedov - focused on the question of where "popular" literature ends and "high"

literature begins.

Yuzefovich, whose "Prince of the

Wind" won the 2001 National Bestseller prize, was reluctant to box in any kind

of writing, but he ventured to associate "popular" literature with demand, and

"high" literature with quality of delivery.

Shaitanov has veered away from

this debate by emphasizing the Booker's role in publicizing serious literature

Russia-wide.

"They tell me that serious

literature can only market from 5,000 to 15,000 copies [throughout Russia]," he

said.

Despite the popularity of

detective thrillers and bodice-rippers, however, Shaitanov is convinced that

Russians would read better books if they could find them in their bookstores.

One of Gonzales Gallego's

responsibilities over the next year will be to promote this vision. The Booker

Prize "is an attempt to open Russia like a door, to satisfy an existing demand

for literature," Shaitanov said.

"To be a successful writer a

literary talent alone is not enough," Votskaya said.

"What is also needed is a desire

to talk to the audiences and, most importantly, the message should be rich in

content - in other words, the author has to have something to say. Gallego does

by far meet all the criteria.

"What the reader is seeking [in a

book] is love and death," Voltskaya added. "And Gallego talks about love and

death with tremendous strength."

Staff writer Rebecca Reich

contributed to this report.

Author Learned Survival in Soviet Orphanages

Maria Danilova

Feb 15,2004.

Afflicted with severe cerebral

palsy, Ruben David Gonzalez Gallego was separated from his mother as a baby and

shunted off into the grim world of Soviet orphanages.

Yet somehow he survived, found

his mother after 30 years and launched a career as a writer -- an endeavor that

recently won him the prestigious Russian Booker Prize for "White on Black," a

heartwrenching account of his travails.

"The book was outstanding not

only as a book, but as a human life," said Igor Shaitanov, secretary of the

Booker literary competition, which in December gave Gallego its $15,000 prize

for 2003. The Russian-language book, published by Limbus Press of St. Petersburg

with an initial print run of just 3,000, was pecked out on a computer with a

single index finger -- one of just two fingers that Gallego can control.

"White on Black" lifts the

Russian taboo on discussing disabilities and reveals the cruelty of a system

that warehouses the physically and mentally impaired. That system forced Gallego,

now 35, to learn at an early age that if he were to survive, he would have to

fight. "If you don't have arms or legs, you are either a hero or a dead man," he

wrote. .

A grandson of Ignacio Gallego, a

prominent leader of the Spanish Communist Party, Gallego was born in the Kremlin

hospital in 1968 to a Spanish mother and a Venezuelan father who were both

studying in Moscow. His twin died at birth; Gallego was diagnosed with an acute

form of cerebral palsy.

Gallego remained with his mother

for just a year and a half, and much of the time he spent in hospitals. One day,

his mother got a message from a hospital.

"They called her and said that

the child was dead," Gallego said in a telephone interview from his home in

Madrid.

In fact, the infant had been

consigned to an orphanage, one of the prison-like institutions where Soviet

society hid its disabled children and adults from public view.

Suffering from malnutrition and

a lack of basics such as a wheelchair, which forced him to crawl to get about,

Gallego spent his childhood being shuttled from one orphanage to another. Then,

when he was a teenager, officials tried to transfer him to an old- age home.

"In orphanages at least, there

are caretakers who would put a spoonful of food in your mouth if you were

paralyzed," Gallego said. "But in old-age homes, which receive scarce funding,

someone like me, who can neither walk nor control his arms, was sure to die of

starvation."

Fortunately, Gallego wrote, the

head of the home refused to take the boy in, assuming that he would die but then

couldn't be buried by an old-age home under Soviet law until he was 18. "Where

am I going to keep him these two years? The refrigerators are broken," Gallego

overheard the director say. He was sent to another orphanage in southern Russia.

There he found better food and education, and was able to graduate from high

school.

"That orphanage was paradise

compared to everything I had experienced before. We had potatoes, we had butter

on bread, we had sweet tea."

After the last Soviet leader,

Mikhail Gorbachev, launched his "restructuring" campaign in the late 1980s,

Gallego was able toescape the world of orphanages and began a life of his own.

"Perestroika brought chaos, and our institutions, which were supposed to be

off-limits for the common people, could now receive visitors," Gallego said.

That opened up a new world for

Gallego. He got married twice and fathered two daughters.

He even traveled to the United

States on a special exchange program, in which Americans with disabilities

explained their experiences in getting greater rights such as access to

buildings and transportation.

Retelling the trip in his book,

he wrote: "I can talk a long time about America. I can endlessly tell about the

individual wheelchairs, 'talking' elevators, smooth roads, ramps and buses

equipped with elevators. About blind programmers and paralyzed scientists. About

how I cried, when I was told that I had to go back to Russia and give up the

wheelchair."

There are as many as 11 million

disabled among Russia's 144 million people, but they are largely invisible.

Streets, public transport and residences are not geared to their needs.

Three years ago, Gallego learned

his mother, Aurora, was working as a correspondent for Radio Free Europe / Radio

Liberty in the Czech capital of Prague.

He moved to Prague to live with

his mother and started painstakingly typing his book.

When his mother was assigned to Madrid, he

followed her there. "If my Mom moved to live in China, without any doubt, I

would have moved there after her," Gallego said.

El nido del escorpión nº 18 Enero 2004

RUBÉN GALLEGO: LA LITERATURA COMO COMUNICACIÓN

Texto de Elena

Alemany

Su novela Blanco sobre negro relata su infancia en orfanatos rusos

Desde hace dos años, Rubén (González) Gallego vive en España, más concretamente

en Madrid, con su madre y su hermanastra. Es nieto de Ignacio Gallego, dirigente

del último partido prosoviético de España, vicepresidente del Parlamento español

durante dos legislaturas y cofirmante de la Constitución Española y nació en

1968 en el hospital del Kremlin, minutos después de un hermano mellizo que

moriría a los pocos días.

Rubén, con parálisis cerebral, pasó un año y medio en un hospital de las afueras

de Moscú. Transcurrido ese tiempo, los separaron y a ella le dijeron que había

muerto. Comenzó entonces el deambular de Rubén de orfanato en orfanato: los

familiares "no presentables" de los altos funcionarios comunistas debían ser

ocultados para no empañar el espej(ism)o del "hombre nuevo" comunista, explica

la madre.

"Aprovechando el desorden general provocado por la perestroika, -según el

epílogo de Blanco sobre negro- Rubén se escapó del geriátrico donde

vivía" y empezó a buscar sus orígenes. Encontró a su madre en Praga, "después de

una epopeya rocambolesca en camioneta por toda Europa". Y entonces se puso a

escribir este libro.

La historia que había comenzado en el orfanato como forma de lucha contra las

adversidades cuajó en una novela titulada Blanco sobre negro que se ha

publicado en Rusia y Francia. En España la editorial Alfaguara acaba de sacar la

cuarta edición. En Alemania, Italia y Taiwán se publicará en breve. La narración

le ha valido el premio Booker ruso.

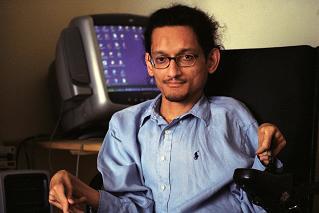

Me encuentro con Rubén en su casa, una tarde de domingo de la época navideña.

Aurora, su madre perdida y encontrada, que también ha conocido la vida en un

orfanato, traduce. Tiene un español muy rico con un ligero acento francés -vivió

en Francia algunos años- y una entonación dulce. Rubén sabe algo de español pero

no lo habla con fluidez, de manera que este interlocutor ágil, culto y políglota

intercala palabras en castellano en medio de su discurso vehemente en ruso,

gesticula mucho a pesar de la escasa movilidad de las manos, fija sus ojos

oscuros en los tuyos mientras pronuncia frases en el idioma de Tolstoi, y

explora sin descanso las posibilidades de inclinación del respaldo de su silla

de ruedas, seguramente para favorecer la circulación de la sangre. Tomo asiento

en un sofá de color claro, en el extremo contrario al de Aurora. Rubén está

montado en su gadgeto-silla, frente a mí. Cada cierto tiempo acciona la

palanca y la silla describe círculos o parábolas con un sonido hidráulico.

Entonces, si levanto la vista, descubro que se aleja, que se acerca o que ha

decidido ponerse cabeza abajo. Saber a qué obedece cada input sonoro no

acaba de tranquilizarme, pero al menos empiezo a decodificar este

espacio-tiempo. Uno o dos metros por detrás de él, entre dos estanterías

plagadas de libros hay un gran espejo vertical, del tamaño de una puerta amplia,

que refleja la salita de entrada. Cada cierto tiempo, de manera inquietante, una

de las gatas aparece por la esquina del espejo. Aparece y desaparece sin hacer

ningún ruido en medio de la casa en semipenumbra. Hay una música de fondo,

agradable, con un cierto matiz étnico que me recuerda a una cinta que compré en

Praga hace años o a los Zap Mamma. Se trata de Bobby Mc Ferrin.

E.A. - ¿Qué papel desempeña para ti la escritura de Blanco sobre negro a

nivel personal?

R.G.

-Toda la vida he contado historias y ahora lo hago en papel.

E.A. - ¿No supone ningún tipo de catarsis o de afirmación?

R.G.

-Si hubiera podido elegir, hubiera preferido hablar con una persona concreta en

vez de tener que escribir este libro. Cuando escribo no sé quién lo va a leer,

cómo lo van a aceptar o si lo rechazarán. El lado más positivo es que cuando

escribo lo puedo proponer a más personas a la vez. Pero cuando hablo con una

persona, mientras voy hablando, voy conociendo a la persona; puedo sentir mejor

lo que le puedo decir a esa persona por la relación que se está formando, si

necesita o quiere algo... En fin, puedo tenerla en cuenta.

E.A. - En tu libro señalas: "Si quieres entender algo debes preguntar a las

personas o a los libros". ¿Hasta qué punto crees que un libro es como una

persona?

R.G.

-Para mí no tiene mucha importancia de qué manera una persona me transmite una

información: a través de un libro, de una nota, de un correo electrónico... Pero

cuando leo un libro comprendo que un libro siempre es menos que la persona.

E.A. - ¿Cómo se produce el encuentro entre madre e hijo?

A.G.

-A través de un director de reportajes, de un reality show. La idea era

hacer un reality show. Pasear a Rubén por toda Europa buscando a su madre.

E.A. - Convertir la búsqueda en un espectáculo.

R.G.

-Y no era muy interesante, claro. Cuando nos encontramos empezó a ser

interesante. Comprendimos que ninguno de los dos es tonto. Que ambos hemos sido

educados en orfanatos...

E.A. - Aurora: ¿tú también eres huérfana?

A.G.

-No, pero por circunstancias pasé parte de mi infancia en un internado ruso de

lujo.

Aurora me ha contestado rápidamente y enseguida ha continuado traduciendo a

Rubén.

R.G.

-Y nos entendimos de inmediato.

E.A. - Tiene que ser muy duro.

R.G.

-Es cruel y feliz al mismo tiempo. Sólo ahora comprendo quién hubiera podido ser

si hubiera estado con mi madre... desde el comienzo.

E.A. - Es una historia increíble.

A.G.

-No es una historia tan rara. Nos están llamando mucho ahora de España. Esta es

una historia española. Mis padres eran emigrantes de la guerra de España. Hubo

muchos casos en España también. Ahora ha salido un libro donde han hecho un

trabajo sobre los niños desaparecidos de la Guerra Civil. A las republicanas que

detenían les quitaban los hijos y los ponían en familias franquistas. Hubo

muchos casos. No es la excepción. Pero de esto apenas se ha hablado o escrito.

Ahora empieza a difundirse, hay un libro o dos sobre el tema. El de Dulce Chacón

y otro libro que le regalé a un editor. Hasta ahora pensábamos que el caso de

Rubén era totalmente extraordinario pero ahora vemos que hay muchos casos.

E.A. - ¿Cuáles son tus escritores favoritos? En la entrevista de los internautas

a través de elmundo.es mencionas a Dostoievsky, Bulgakov, Gertrude Stein, los

hermanos Grimm...

R.G.

-Si me preguntas por escritores yo empezaré a hablar y terminaremos por la

mañana... Pero no comprendo la pregunta.

E.A. - Este tipo de pregunta se suele hacer para conocer las influencias del

escritor. Dicho de otro modo: ¿Qué libros tienes en la mesilla? ¿A quién relees

con más frecuencia?

R.G.

- No entiendo ese tipo de preguntas: a ti podría decirte ahora dos libros y

luego llegaría otra persona y le diría otros libros distintos... Los libros que

yo nombrara no tendrían ningún significado como elección. Una persona que me

entrevistaba me pidió que citara todos los libros que he leído. Le dije que

varios miles, me miró como si estuviera loco y se acabó la conversación.

E.A.

- Aquello, más que una pregunta, era una provocación...

R.G.

- Estoy leyendo a Saint Exupéry. Cuando quiero algo, leo o releo algún libro en

concreto...

E.A. - ¿Has cultivado el cuento?

R.G.

-(Contesta el propio Rubén en español tras oír la traducción de la pregunta).

No sé. No estoy seguro. Yo voy a hacer lo que hago. Si (la gente) va a comprar

(mi libro) yo voy a seguir escribiendo. Punto. Si no van a comprar no voy a

escribir. Puedo escribir o puedo no escribir. Para mí no importa nada.

Interrumpe Aurora.

A.G.

-(Rubén) es duro.

R.G.

-(En español). Es la vida.

A.G.

- Si la gente no lee, significa que no quiere escuchar tus historias y entonces

para qué escribir... Rubén es así. Haría otras cosas. De igual forma, si yo

hablo y no me escuchan, entonces buscaré otras personas.

E.A.-

U otro lenguaje.

A.G.

(Aurora sigue hablando por propia iniciativa)-O empiezo a pintar, y si no

vendo mis cuadros empiezo a hacer música y si no...

E.A.- Es decir, el interés es la comunicación. El libro no se considera una obra

de arte con un valor intrínseco que pueda ser reconocido en el futuro aunque

ahora no se aprecie...

R.G.

-No tomo en consideración el futuro. Si encuentro una forma de comunicación

mejor, utilizaré esa forma.

A.G.

-Según la educación que hemos tenido, es ahora o nunca. La comunicación en el

instante. En nuestra situación se tiene poco interés por hacer obra y se busca

más bien el placer de la comunicación instantánea... Porque a mí como a Rubén me

trasladaron de sitio... Yo sé muy bien lo que quiere decir Rubén. No sabes lo

que va a pasar mañana. También por muchísimos otros factores. Escribir es un

placer.

E.A. -¿Escribir es un placer?

R.G.

(Rubén no espera a que su madre le traduzca al ruso. Me contesta en español)-Escribir

es un trabajo duro, que si lo tienes que hacer, lo haces. Yo puedo hacer eso,

puedo hacer lo otro. Si el libro no se vendiera, buscaría otra forma de

comunicarme.

A.G.

-Hablar con alguien es un placer.

E.A. - Rubén, ¿cuánto tardaste en escribir tu novela?

R.G.

-Tardé cuatro meses en escribir Blanco sobre negro.

E.A. - ¡Qué rápido! Está muy bien.

R.G.

-Yo sé. Y el libro con el que estoy también podría haberlo acabado en cuatro

meses, pero en agosto hacía mucho calor en Madrid y estuve casi muriendo.

Después empezaba la promoción del libro, a la que dediqué dos meses y después el

Booker Price. Estamos muy cansados pero por fin voy a terminar mi libro.

A.G.

- Increíble la reacción en Rusia. Está dando entrevistas todo el día.

R.G.

- En Rusia un hombre compró 10.000 ejemplares para mandarlos a las cárceles, a

las escuelas, a los hospitales.

E.A. - Eso es comunicación.

R.G.

- Sí.

E.A. - ¿La promoción en España es anterior al Booker?

R.G.

Son dos cosas paralelas, sin relación.

E.A. - ¿Cómo fue el proceso hasta la publicación por parte de

Alfaguara?

A.G.

- Me llamó Amaya Elezcano, editora de Alfaguara, y estuvimos hablando. Leyó el

libro y quiso conocer a Rubén y fue Rubén a Alfaguara y no lo dejaban irse... y

salió el libro y vinieron todos los del Grupo (Santillana) y estuvo muy bien. La

hermana de Rubén hizo la portada con una foto de él. Los franceses prefirieron

el diseño de un fotógrafo muy de moda que puso un niño rumano (en Francia

causaron mucho impacto las imágenes de orfanatos rumanos) y un crítico popular,

Michel Polac, conocido por no entusiasmarse fácilmente, escribió dos artículos

en Charlie Hebdo sobre el libro de Rubén y además dijo que él hubiera preferido

una foto del autor.

Frankfurter

Allgemeine Zeitung vom 19.06.2004 Seite 46

Kerstin Holm

Funksprüche

aus der Alltagshölle

Höchste Schicksalsladung: Ruben Gonzalez Gallegos Aufzeichnungen aus der

Unterwelt russischer Anstalten

Ruben Gonzalez Gallego: „Weiß auf Schwarz“. Ein Bericht. Aus dem

Russischen übersetzt von Lena Gorelik. Verlag SchirmerGraf, München 2004.

224 S., geb., 17,80 €.

Dieses Buch liest seinen Leser. Der Autor, Sproß der Liebe einer spanischen

Juniorkommunistin während ihres Moskauer Studiums, wurde ohne die physische

Grundausstattung des Normalmenschen, funktionsfähige Arme und Beine, auch ohne

Vater und Mutter, auf einen Lebensweg geschickt, der ihn durch die geschlossenen

Anstalten Rußlands führte. Die Essenz des Menschlichen, abzüglich der

Vermittlung körperlicher Fertigkeiten und westlicher Zivilisationspolster – wer,

wenn nicht dieser Mann, sollte ihrem Wesen nahegekommen sein.

Das Bild vom Menschenwurm verliert seine theologischen und literarischen Würden

und wird zur bloßen Tatsache. Jedenfalls für denjenigen, der, um nachts zur

Toilette zu gelangen, sich aus dem Bett fallen läßt und nackt durch eisige Flure

kriecht. Was die versehrte Waise diese und viel härtere Prüfungen überstehen

läßt, ist ein Kampfgeist, der menschliche Niedertracht schweigend registrieren,

sich an Erlebnissen von Liebe oder Schönheit jedoch vollzusaugen versteht wie

ein Kamel, bevor es die nächste Wüste durchquert.

Ein Held sei er, stellt Ruben Gonzalez sich vor, weil ihm keine andere Wahl

bleibe. In seiner Lebensprosaernte, die nach ihrer russischen

Erstveröffentlichung ihm im vergangenen Jahr den russischen Booker-Preis

einbrachte, kristallisiert sich die Welt zu zweiundvierzig Schlüsselepisoden,

-figuren, -bildern von höchster Schicksalsladung. Der im Kinderheim Bücher

verschlingende Autor begreift nicht, wie gesunde Menschen überhaupt verzagen

können. Ein einbeiniger Freund, der einen Winter lang für den Zweikampf mit

einem gesunden Nebenbuhler trainiert hat, ist über dessen Willenlosigkeit

erschüttert.

Auch jener krampfgelähmte Anstaltsgenosse, der sich nachts zum

Schulaufgabenmachen ins Klassenzimmer schleppt, oder der vom Schlag getroffene

Straflagerveteran, der mit seinem bleischweren Krückstock die Zwangsverlegung in

die Sterbeabteilung abzuwenden vermag, lassen spüren, wie der Kompressionsdruck

von Lebenswidrigkeiten Sinne schärfen und Energien mobilisieren kann, während

sie unter komfortablen Bedingungen abstumpfen. „Man möchte sich geradezu etwas

abschneiden“, kommentiert der Moskauer Verleger Alexander Iwanow die Wirkung der

Lektüre.

Gonzalez’ Buch nimmt mit in eine Normalhölle, aus der kaum jemals literarische

Funksprüche an die lesende Öffentlichkeit dringen. Darin werden invalide Waisen,

die keine Berufsarbeit leisten können, nach dem Schulabschluß kurzerhand ins

Altersheim verfrachtet – was sie in der Regel um wenige Wochen überleben. Wie

jener mit achtzehn Jahren zehn Kilo schwere Genka, der soeben noch für eine

Schülerin schwierige Mathematikaufgaben löste. Gonzalez hat aus dem Altersheim

fliehen können. Seine Aufzeichnungen aus dieser Unterwelt führen vor Augen, daß

sich der Mensch auch im hiesigen Überlebenskampf zu furchtbarer Erhabenheit

aufraffen kann. Beispielsweise jene Greisin, die andere füttert, um nicht selbst

bettlägerig zu werden, oder jener beinlose General, dessen Selbstmord

schrecklich und würdevoll ist wie der eines antiken Stoikers.

Die von den Erziehern empfohlene Lebensweisheit besteht in pflichtschuldiger

Dankbarkeit, Geduld und der Universalmedizin Wodka. Der gelehrige Spanier

beherzigt alle drei. Seinen Lebenstreibstoff jedoch hat er offenbar aus der in

Rußland zäh wuchernden Liebe gesogen, deren merkwürdigen Metamorphosen er

eindrucksvolle Denkmäler setzt. Etwa jener alten Frau, die als Einbrecherin der

Wohltätigkeit über den Anstaltszaun klimmt, um das hilflose Kind mit Pfannkuchen

zu füttern. Den göttergleichen Pflegeschwestern, die man aus Kindheits- und

Krankheitstagen kennt. Oder aber jenem betrunkenen Soldaten, den der Held an

seine verstümmelten Afghanistan-Kameraden erinnert. Es erscheint wie ein

Sinnbild für die lebensspendenden Mißverständnisse, zu denen auch die Wortkunst

gehört, wenn das trüb flackernde Bewußtsein dieses wilden Mannes in ihm den

Bruder erkennt.

FRANKFURTER

RUNDSCHAU

Im

Dunkeln tuscheln

Der Lebensbericht des behinderten Schriftstellers Ruben Gonzalez Gallego

VON

CHRISTIAN MÜRNER

Ruben Gonzalez Gallego:

"Weiß auf Schwarz. Ein Bericht". Aus dem Russischen von Lena Gorelik.

SchirmerGraf Verlag München 2004, 218 Seiten, 17,80 Euro.

"Ich

bin ein Held. Es ist einfach, ein Held zu sein. Wenn du keine Arme oder Beine

hast - bist du entweder ein Held, oder du bist tot." Auf dem Umschlag der

deutschen Übersetzung von Gonzalez Gallegos Buch, das 2003 den russischen Booker

Prize erhielt, ist ein dunkelhäutiger Junge, schwarzäugig, mit großen Ohren,

Kurzhaarschnitt und einem roten Halstuch abgebildet. Es ist ein Kinderfoto des

Autors. Ruben Gonzalez Gallego wurde 1968 in der Klinik des Kreml geboren. Sein

Großvater war Generalsekretär der Kommunistischen Partei Spaniens und befreundet

mit Picasso. Gleich nach der Geburt trennte man Mutter und Sohn. Die

Feststellung, dass Rubens Beine gelähmt und die Feinmotorik seiner Hände

beeinträchtigt bleiben, genügte dazu.

"Ich

bin ein Held. Es ist einfach, ein Held zu sein. Wenn du keine Arme oder Beine

hast - bist du entweder ein Held, oder du bist tot." Auf dem Umschlag der

deutschen Übersetzung von Gonzalez Gallegos Buch, das 2003 den russischen Booker

Prize erhielt, ist ein dunkelhäutiger Junge, schwarzäugig, mit großen Ohren,

Kurzhaarschnitt und einem roten Halstuch abgebildet. Es ist ein Kinderfoto des

Autors. Ruben Gonzalez Gallego wurde 1968 in der Klinik des Kreml geboren. Sein

Großvater war Generalsekretär der Kommunistischen Partei Spaniens und befreundet

mit Picasso. Gleich nach der Geburt trennte man Mutter und Sohn. Die

Feststellung, dass Rubens Beine gelähmt und die Feinmotorik seiner Hände

beeinträchtigt bleiben, genügte dazu.

Er kam ins Heim. Seiner Mutter sagte man, er sei wie sein Zwillingsbruder nach

der Geburt gestorben. 1990, zur Zeit der Perestroika, gelang ihm die Flucht aus

dem Altersheim, in das er zuletzt abgeschoben wurde. Soweit protokollarisch die

Basis des Berichts von Gonzalez Gallego. Sein Text ist ein prägnanter

literarischer Versuch, sich über eine beklemmende Kindheit Klarheit zu

verschaffen. Gonzalez Gallego bezeichnet sein Buch als ein Bajonett, das

einschneidet, in das, was aussichtslos schien. Es entstehen bedeutsame

Fragmente, die sich in der Lektüre zusammenfügen. Eines Tages schleicht sich ein

Hund aufs Gelände des Kinderheims. In einer solchen Einrichtung ist er aus

hygienischen Gründen eigentlich unhaltbar. Doch wie ein Lauffeuer spricht sich

seine Anwesenheit herum unter den Kindern und jedes will ihn streicheln. Das

Direktion sagt: Der Hund muss weg! Es gibt nur ein Problem, das dem Weltbild des

Heims für behinderte Kinder widerspricht: Dem Hund fehlt eine Pfote. Eine

Krankenschwester pflegt die Wunde sogar. Unter dem Vorbehalt, dass die Kinder

sich die Hände waschen und der Tierarzt eine Unbedenklichkeitsbescheinigung

ausstellt, wird eine Ausnahme genehmigt. Im Werkunterricht wird eine Hundehütte

gezimmert. Denjenigen Kinder, die den Ball nicht werfen konnten, legt der kluge

Hund mit dem roten Fell den Kopf in den Schoß.

Im Kinderheim machen die Erwachsenen das Licht aus; das heißt aber nicht, dass

die Kinder dann schlafen. Die Kinder beginnen sich zu unterhalten, weil man im

Dunkeln über alles reden kann. "In jener Nacht wurde über die Eltern geredet."

Jeder hatte die besten Eltern. "Nicht alle hatten einen Vater. Wer aber einen

hatte, der hatte den allerallerbesten." Einer erzählt davon, wie der

Nachbarjunge vom Vater ein Fahrrad geschenkt bekam, das alle bewunderten. Und

sein Vater, der kein Geld hatte und oft viel trank, nun überlegte, was er

besseres schenken könnte. Eines Tages brachte er ein Radio mit. "Auf der Skala

stehen alle Städte der Welt." Was ist schon ein Fahrrad dagegen - "ein Stück

Eisen mit zwei Rädern. Weiter nichts!" Vor allem für einen Jungen ohne Beine.

Nachts, vor dem Einschlafen eine solche Erzählung, das ist die Erfindung der

Welt der Literatur.

Gonzalez Gallego träumt davon, laufen zu können, weil diejenigen, die laufen

können, auch mithilfe von Krücken, besser behandelt werden. Nicht laufen zu

können, heißt im Kinderheim auch, nicht klug, ja, überhaupt kein Mensch zu sein.

So spielt Gonzalez Gallego den Dummen. Er betrachtet es als schlechte

Angewohnheit, die er sich im Kinderheim aneignete, alle Menschen in Freunde oder

Feinde aufzuteilen. Gonzalez Gallego dankt, nicht ohne Sarkasmus, "dem

sowjetischen Staat, der mich groß gezogen hat". Solche und andere schonungslose

Stellen verführen dazu zu fragen: Stimmt das wirklich, was Gonzalez Gallego

erzählt? Er beteuert es mit Nachdruck und ergänzt, dass er auch dann, wenn er

die Protagonisten komponiere, nicht von der Wahrhaftigkeit abweiche. Sein

Alptraum war, was mit ihm passieren würde, wenn er erst erwachsen geworden wäre.

Alle, die nicht laufen konnte, erwartete das Altersheim. Das wusste er früh und

hatte Angst davor. Wie genau Gonzalez Gallego entkam, wird man vielleicht in

weiteren beeindruckenden Berichten erfahren.

N Z Z

Online

Neue Zürcher

Zeitung, 16. Juni 2004, Ressort Feuilleton

Das Kind, die Norm, der Tod

Ruben Gonzalez

Gallego berichtet von seinem Unglück

Adam Olschewski

Ruben Gonzalez

Gallego: Weiss auf Schwarz. Ein Bericht. Aus dem Russischen von Lena Gorelik.

Verlag Schirmer Graf, München 2004. 218 S., Fr. 32.30.

Das Ausmass des Unglücks, des Elends kann man unmöglich fassen.

Selbst nach der Lektüre nicht. Ruben Gonzalez Gallego möchte auch gar nicht das

Unglück allzu sehr hervorkehren. «Ich schreibe über das Gute, über den Sieg,

über die Freude und die Liebe», sagt er im Nachwort zu «Weiss auf Schwarz»,

einem ins Literarische gehobenen Tatsachenbericht, der sich aus seiner Biografie

nährt und mit dem er als Autor debütiert. Der Begriff des Guten wird hierbei

relativiert wie selten.

Gallego, aus Spanien stammend, wurde 1968 zufällig in Moskau

geboren. Er kam mit Zerebralparese auf die Welt, was offenbar in diesem Fall

bedeutet, dass er seine Hände eingeschränkt, seine Beine gar nicht benutzen

kann. Er wurde von der Mutter getrennt, was folgte, war eine Odyssee durch

sowjetische Kinderheime. Heute, da er seine Familie nach Jahrzehnten ausfindig

gemacht hat, lebt Gallego in Madrid. All diese Fakten liefert uns seine Mutter

in einem zweiten Nachwort.

Im Buch selbst, auf Russisch verfasst, erklärt Gallego an

Hintergrund nicht viel. Er wirft einen ins Geschehen hinein. Erst nach und nach

kann man sich sein Los zumindest teilweise zusammensetzen. In den 42 Kapiteln,

manches davon kaum eine Seite lang, schildert er sich vorwiegend als Kind. Mal

ums Mal nimmt er eine simple Sicht gegenüber dem Geschehen ein, die sich im

Sprachduktus vermittelt, der unter anderem einfache Sätze und Wiederholungen

bevorzugt. Das hat neben einer Portion Naivität mitunter eine Distanz zur Folge,

die dem Bericht gut tut, denn nur so lässt sich wohl vom beinahe

Unaussprechlichen erzählen. Die Zustände in den Kinderheimen sind nämlich genau

das - unaussprechlich. Gallego klagt nicht an, was etwas unverständlich bleibt

angesichts der Bilder, die er fortwährend erzeugt. So wird etwa das Essen streng

rationiert und ist mindestens wenig abwechslungsreich, die Patienten werden

meist sich selbst überlassen, in Unrat und Langeweile erstickend, kaum fähig,

sich zu rühren. Die Betreuer sind hartherzig, die Lehrer selten wohlmeinend, die

Initiationsriten für Neuankömmlinge eher grob.

Es ist eine eigene, vom System verleugnete Welt. Dies stellt

einen der interessantesten Aspekte des Buches dar: Wie eine Staatsordnung, vom

Gleichheitsgedanken theoretisch im Übermass beseelt, mit Leuten umging, die der

Norm nicht entsprachen. Wie sie diese wegschob und eingehen liess. Im Prinzip

scheinen alle Verfehlungen jedweden gleichschaltenden Systems durch, ja alle

Unmenschlichkeiten, die Menschen Menschen antun können.

Das, was wir zu sehen bekommen, reicht aus. Die Szenen im

Altersheim sowieso, wohin die Kinderheiminsassen nach dem Schulabschluss

gebracht werden, die mit 15 Jahren also unter Rentnern und im unterschiedlichen

Grad Versehrten zu leben gezwungen werden. Dort, im Stich gelassen von allem und

jedem, sterben sie dann.

Während viele Kapitel aus der Periode der Sowjetunion (Brief,

Altersheim, Sünderin, Offizier) trotz sachlichem Schreibstil starke Emotionen

auszulösen vermögen, fallen die Texte danach etwas ab. Es ist lediglich die

Person des Verfassers, die fortan das Konvolut zusammenhält. Die Texte reden von

Amerika und dem Leistungsdruck dort, vom Leben mit der Behinderung - über

nichts, was man nicht kennt. Auch die Einfachheit der Sprache (Gallego lässt

alle Figuren im gleichen Tonfall reden) erschöpft sich ein wenig. Nicht schlimm.

Wir haben verstanden, und - wichtiger - wir haben mitgefühlt.

Project:

"НаСтоящая

литература"

Наташа КУРЧАТОВА

14-7-2003

Рубен Давид

Гонсалес Гальего ::: Черным по белому, Лимбус-пресс, 2003

Живя в Мадриде, Рубен Давид Гонсалес Гальего пишет по-русски. И не только и не

столько потому, что, внук видного испанского коммуниста, он провел детство в

Советском Союзе. По его мнению, только "великий и могучий" может адекватно

передать то, что творилось в детских домах для инвалидов СССР.

Описанию этого ужаса и посвящен его блистательный литературный дебют -

автобиографический роман в рассказах "Белое на черном", ставший сенсацией уже в

журнальной публикации.

Издатели завидуют тем, кто прочтет это впервые. Во-первых, книга очень веселая:

автор как никто умеет находить смешное в страшном. Во-вторых, он сумел

конвертировать личный опыт в подлинное искусство, если. Конечно, считать

искусством то, что помогает жить.

Читающий публике предъявили шорт-лист литературной премии Андрея Белого. Одним

из самых громких номинантов стал Рубен Давид Гонсалес Гальего, чья

автобиографическая книга "Черным по белому" была напечатана в первом номере

"Иностранки" за 2002 год.

Сразу поясню читателям, которых удивило пышное испанское имя автора в шорт-листе

русскоязычной премии "за радикальные инновации в сфере тематики и художественной

формы": книга написана по-русски, отпечатана одним указательным пальцем левой

руки. Тридцатитрехлетний Рубен Гальего - внук генерального секретаря компартии

Испании Игнасио Гальего, сын гражданина Венесуэлы, в чьих жилах индейская кровь

течет пополам с кровью испанцев - уроженцев Андалузии и Басконии.

Гальего появился на свет в России, в Кремлевской больнице. На его судьбу

примерно одинаково повлияли непростые отношения Советского Союза с компартией

Испании и франкистским правительством, а также врожденное заболевание - детский

церебральный паралич. Вскоре после рождения ребенка матери Ауроре Гальего

сообщили о его смерти. С тех пор началась долгая история мытарств по детским

домам и специализированным клиникам, в конце которой маячил неизбежный дом

престарелых, куда по достижении пятнадцатилетнего возраста отправляли

"неполноценных", и бессмысленная смерть на больничной койке. Обо всем этом

Гальего, ныне гражданин Испании, и поведал в своей книге.

С точки зрения текста, "Черным по белому" трудно назвать "инновацией" в смысле

формы - книга написана ровно, просто, даже безыскусно, представляет из себя до

умопомешательства тихие автобиографические зарисовки. С другой стороны, в

отношении тематики и личных обстоятельств необычность Гальего как автора

безусловна.

Этот своеобразный ответ на "кичевых" персонажей премии "Национальный Бестселлер"

вроде радикального коммуниста Александра Проханова или юной старлетки Ирины

Денежкиной настолько же спорен, насколько и силен. Такое ощущение, что давно

заявленная в актуальной литературе "смерть автора" обернулась не просто

бессмертием, но до банальности обостренной персонификацией текста, полным его

слиянием с "жизненным текстом" пишущего.

Такая, прямо сказать, прямолинейная трактовка лишний раз напрашивается при

взгляде на соседей Гальего по шорт-листу - молодого прозаика-программиста Андрея

Башаримова, выросшего и состоявшегося во всемирной паутине Интернет, и

обвиняемого известно в чем Эдуарда Лимонова с его "Книгой воды". Впрочем,

последний номинант в моих комментариях явно не нуждается.

На этом фоне две оставшиеся "рубрики" премии Белого - поэзия и гуманитарные

исследования - кажутся продолжением корпоративной свадьбы интеллектуалов, прочно

обосновавшейся в башне слоновой кости. С одной стороны, остается жалеть, что

столь добрая традиция явно остается за бортом общественного внимания. С другой -

именно люди, подобные Гальего, возвращают искусству осязаемую витальность

творческого акта.

Наверное, вышеизложенную ситуацию можно счесть веянием времени, вытаскивающего

на свет самые трепещущие нервы эпохи, не гнушаясь раскрученной спекулятивности

Проханова, или же, напротив, почти неприличной подлинности черно-белых

откровений Рубена Гальего.

Но даже при весьма недалеком размышлении приходится задать себе вопрос: "А было

ли когда-нибудь иначе?"

Если и было, то

недолго.