4-10-2007

A Lobotomia

September 14, 2007

Books of The Times

By WILLIAM GRIMES

MY LOBOTOMY

A Memoir

By Howard Dully and Charles Fleming

Illustrated. 272 pages. Crown. $24.95.

978-0-307-38126-2 (0-307-38126-9)

|

As a child, Howard Dully was a handful and a half. Wayward, high-spirited, dreamy, careless and slovenly, he drove his father and his stepmother to distraction. Unlike millions of other boys fitting the same description, at age 12 he underwent a transorbital lobotomy to cure his supposed psychological problems. Steel spikes were driven through the back of both eye sockets and into his brain to sever neural connections between the thalamus and the frontal lobe. Forty years of misery ensued, recalled by Mr. Dully in a celebrated documentary broadcast on National Public Radio in November 2005 and now, in collaboration with Charles Fleming, in the harrowing “My Lobotomy.” It is a painful tale with two unanswered questions at its heart. The first is, Why? For most of his life Mr. Dully struggled to find a reason for the decision by his father and stepmother to deliver him, in 1960, into the hands of Dr. Walter Freeman, the self-deluded zealot who pioneered the lobotomy as a cure for all manner of personality disorders. In pursuing this quest, he became the first of Dr. Freeman’s patients to retrieve and study his own medical file, with Dr. Freeman’s detailed notes, quoted extensively to chilling effect in the book. |

|

Mr. Dully, now a bus driver in San Jose, Calif., with a wife and two sons, never does find out why. By reconstructing his past, however, he comes to realize that he has been asking an unanswerable question. But it is not clear whether he fully recognizes the other mystery that haunts his story: Was it the lobotomy or his feelings about it that shaped his life?

As he delves into his wretched childhood and the twisted psychology of his father and stepmother, his operation seems less like a turning point than an overcharged symbolic event. In a curious way, this only makes the story more intriguing.

Mr. Dully lost his mother when he was 4. She died giving birth to his younger brother, who was born with severe brain damage. His father, scarred by the Depression and overseas military duty in World War II, was emotionally distant and physically brutal. His stepmother, the cast-off child of a Jazz Age flapper, survived one marriage to an alcoholic and, with two children of her own in tow, came into little Howard’s life like an avenging angel. A harsh disciplinarian and obsessive housecleaner, she took an instant dislike to the boy, whom she regarded as dirty, rebellious and incorrigible.

The truth of what happened next is impossible to determine. “My Lobotomy” presents competing narratives, none of them entirely reliable.

Like any adult looking back on his childhood, Mr. Dully summons up facts mingled with dreamlike images, the grown-up world seen through a child’s eyes and experienced with a child’s emotions. Dr. Freeman’s notes, written in dispassionate style, reflect a synthesis of the parents’ distorted descriptions and his own clinical observations. Court records add a third layer to be interpreted. The past, ultimately, is irretrievable.

By his own admission, Howard was difficult. He stole, he lied, he broke rules. He was constantly in trouble at school. He smoked. Howard’s stepmother supplied a long list of complaints to Dr. Freeman, some serious, many trivial.

“Has monkey-like gestures and mannerisms — i.e., scratching head and body,” Dr. Freeman transcribed. “Won’t move when told time is short. Doesn’t use good judgment. Comprehension not good. Seems useless to convey reasons. Won’t do homework.”

All six of the psychiatrists consulted by Howard’s stepmother before she went to Dr. Freeman told her that her stepson was normal. Four said that she was the problem. Dr. Freeman, after initially finding nothing seriously wrong with his young patient, eventually decided that he was schizophrenic and a prime candidate for a lobotomy.

The operation lasted perhaps 10 minutes. Howard, although initially dazed and disoriented, gradually recovered his faculties, although, Dr. Freeman noted in a follow-up visit, “Howard seems to have no particular depth of feeling about anything.” It is unclear whether the lobotomy changed Howard’s personality or whether it accounts for his subsequent troubles, which were many but seem a direct result of long-established patterns of behavior.

“I’ll never know what I lost in those 10 minutes with Dr. Freeman and his ice pick,” Mr. Dully says in his radio documentary. “By some miracle, it didn’t turn me into a zombie, or crush my spirit, or kill me.”

What it did was put him outside human society. Mr. Dully, regarding himself as a freak, wandered aimlessly through life. Forced from his family home at 14, he spent years in juvenile homes and later state mental hospitals, primarily as a way of keeping out of prison. He drifted from job to job, drank heavily and used drugs, relying on disability checks to finance his marginal lifestyle. “All I had to do was be the guy who had the lobotomy,” he writes.

Mr. Dully eventually finds a woman who loves him, a love he returns to her, her son and the son they have together. Therein lies the answer to the biggest question of Mr. Dully’s life. The lobotomy, although terrible, was not the greatest injury done to him. His greatest misfortune, as his own testimony makes clear, was being raised by parents who could not give him love. The lobotomy, he writes, made him feel like a Frankenstein monster. But that’s not quite right. By the age of 12 he already felt that way. It’s this that makes “My Lobotomy” one of the saddest stories you’ll ever read.

His lobotomy, his recovery, in his words

Edward Guthmann, Chronicle Staff Writer

Wednesday, September 26, 2007

Until he was 5, Howard Dully was a happy child. That was the year his mother, June, died of cancer. June was "loving and indulgent," Dully writes, so devoted that his father once said, "I could've dropped dead and it wouldn't have made a bit of difference. She had you."

After his mother's death, neighbors started sewing and cooking, doing laundry for the Dullys. One of them, Lucille "Lou" Cox, became his stepmother two years later. Rigid and punitive, Lou hated Howard. When he was 12, she arranged for the boy to have a transorbital lobotomy.

The surgeon, Dr. Walter Freeman, did the procedure at Doctors General Hospital in San Jose. After sedating Howard with four jolts of electroshock, Freeman inserted two skewer-like steel knives into his skull, entering through the inside of the right and left eye sockets.

"(He) swirled them around," Dully writes, "until he felt he had scrambled things up enough." The lobotomy took 10 minutes to perform. The charge was $200.

This is the story that Dully, a 58-year-old San Jose bus driver, tells in his memoir, "My Lobotomy" ($24.95, Crown Publishers). It's a gruesome but compulsively readable tale, ultimately redemptive. Unlike most lobotomy patients - some became vegetables, 15 percent died - Dully was relatively unscathed.

"The biggest impact it made on me was my self-esteem," Dully says during a conversation in Jimmy's, a San Jose coffee shop with early-'60s decor. "You know, they changed me. They rearranged me. 'Am I me any more? Am I really crazy and don't know it?' These things all go through your mind."

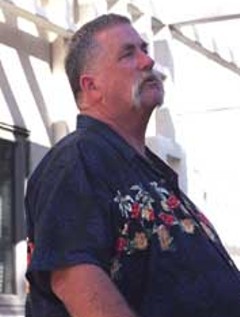

Dully is hardly the picture of victimhood. Six-foot-seven, 330 pounds, he's a bear of a man with enormous hands, a voice like a cello and the visage of a grizzled biker. Until last year, he wore his mustache super-long and droopy, like Yosemite Sam, and then decided "I was hiding behind it."

No one would want to mess with this guy, but when you sit down with Dully you find a gentle, vulnerable man who speaks easily of emotional hurt. Traces of sadness are embedded in his face. His mood is subdued - or at least leveled - by the Prozac he's taken for four years.

What's surprising is Dully's lack of bitterness. Despite the lobotomy, despite the subsequent years when he was bounced from foster home to juvenile hall to mental institution - he says "there's no point" in being angry.

"I've worked through all that. The only person it's gonna hurt is me. My biggest question is 'Why?' Why would an adult play the game to the extent it was played? ... I'm not going to say I was walking on water and here came the evil stepmother who just had things poked into the back of my head. But I don't feel I did anything to deserve a lobotomy."

At 12, Dully was already 6 feet tall - a "hellious" kid, in his words. He lied and shoplifted on occasion. He smoked cigarettes. Hated homework. Because his dad worked three jobs and was never home, his stepmom meted out the discipline. "Lou was a fairly small woman and it finally got to the point where she'd spank me and I'd laugh. I think that scared her."

In "My Lobotomy," Dully and co-writer Charles Fleming describe how Lou consulted six psychiatrists in her search for a solution, and was told by four of them that she was the problem and not Howard. Finally, she found Freeman and convinced him that her stepson was a candidate for lobotomy.

Freeman, subject of a recent book, "The Lobotomist" by Jack El-Hai, didn't need to be lobbied or prodded. A psychiatrist and neurologist, he didn't invent the lobotomy but popularized and promoted it. Full of hubris, he touted the procedure's benefits at medical conventions, behaving, his partner James Watt said, "like a barker at a carnival."

When patients suffered permanent brain damage, Freeman was unfazed. "Maybe it will be shown," he said, "that a mentally ill patient can think more clearly and constructively with less brain in actual operation."

Given the brutality and imprecision of the lobotomy procedure, Dully is luckier than most survivors. He believes his tear ducts were damaged by the lobotomy and attributes his sinus problems to the procedure. His thinking processes, he says, "seem to go off in different directions to reach conclusions, instead of focusing down one path."

More than anything, he feels a loss - a sense of having missed his youth. "I still go to Los Altos, to the old house where I lived (before the lobotomy). Go to the schools that I went to. I get out of the car and walk around. I'd do it daily if I had time. For some reason it fascinates me.

"I think it gives me an attachment to when I had a family," he says, clearing his throat. "A normal family life. Mom and dad and brothers. Because from 12 years on my life was not normal."

Throughout his 20s and 30s, Dully had problems with alcohol, drugs and homelessness. He went sober in 1985 and quit smoking in 1994 after a heart attack. In his 40s, he went back to school and got a degree in computer information systems but found he was too old to find work in that youth-centric market.

"I'll never get to where my brothers are, because I started at 40 and they started at 20. I lost 20 years. It happened too late in some respects. That's just the way it is."

Dully credits his wife, Barbara, with putting him on a positive track. They met 22 years ago and got married in 1995. Wedding pictures show them in gown and tux, astride matching motorcycles. Dully has two sons, 30 and 27, from an earlier relationship and has worked as a bus driver for 10 years. He's on a leave of absence from San Jose Charter Bus while he promotes his book.

"My Lobotomy" began as a radio documentary on NPR's "All Things Considered" in November 2005. Producers Dave Isay and Piya Kochhar intended a profile on Freeman but when they found Dully, who had recently started researching lobotomy on the Internet, they fell in love with his story. They decided to focus on him instead, and urged him to narrate the piece in his gentle, resonant baritone.

Isay and Kochhar took Dully to Freeman's medical archives at George Washington University in Washington, D.C. "My file has everything," he says in the narration. "A photo of me with the ice picks in my eyes, medical bills. But all I care about are the notes. I want to understand why this was done to me."

The NPR piece captures a conversation with Dully and his father, Rodney, a former schoolteacher who was later divorced from Lou. "I was manipulated, pure and simple," his dad says in regard to the lobotomy.

But when Howard breaks down and professes his love to his dad, his father answers, "Whatever made you think I didn't know that? You shaped up pretty good!" He doesn't say "I love you" back.

"Ever since my lobotomy I've felt like a freak," Dully says at the end of the broadcast. (But) I know my lobotomy didn't touch my soul. For the first time, I feel no shame. I am, at last, at peace."

The response to the broadcast was huge. So many e-mails flooded in that NPR's Internet server collapsed. Today, Dully says, there's interest from Hollywood producers to make a TV movie or feature film from his book. "I'd love it, provided it's done with truth. I don't want any fictional account making someone out worse than they were or better than they were."

There's also a playwright in New York who, inspired by the NPR documentary, has written a play about Dully called "The Memory of Damage."

Dully, who looks like a Buddha as he sits in his favorite coffee shop, seems to regard the celebrity as a cosmic joke. For someone who spent his life plagued by self-doubts, who says he's still intimidated by his father, it's difficult to accept this attention.

"I tease my wife and other people, and say I have a swollen ego," he chuckles. "But I don't have any news people camping outside my door. I don't live in any mansion.

"My idea for writing the book was first to get a little closure - which I find a little selfish, but that's OK. The other reason was to help people to think about how we treat each other daily. Not just loved ones but everybody.

"Something you start here or say here may affect somebody's whole day, maybe their whole life. Ten minutes of what Freeman did to me has affected me for 47 years."

|

September 9, 2007

BY JACK EL-HAI

MY LOBOTOMY

By Howard Dully and Charles Fleming

Crown, 288 pages, $24.95

For decades, in books, plays and movies, giving a lobotomy was about the worst thing doctors could do to patients besides kill them. Lobotomies threaten the vulnerable protagonists of such works as Suddenly, Last Summer by Tennessee Williams and Daybreak by Frank Slaughter. One extinguishes the spirit of the hero of Ken Kesey's One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. Let's not even think about Hannibal Lecter's hobbies. A lobotomy left you brainless, without a soul or a life.

But lobotomies, which were performed on about 40,000 Americans to treat a variety of psychiatric problems during the mid-20th century, were not always devastating to patients. Some returned to their homes, families and jobs after their operations. For them, there was a life after lobotomy -- one that didn't involve drooling or permanent institutionalization.

Take the remarkable case of Howard Dully. His memoir My Lobotomy, co-written with novelist and Hollywood journalist Charles Fleming, is unique as a record of a lobotomy patient's life. I first met Dully in 2005 at the premiere of the public-radio documentary that spawned his book. (Full disclosure: I served as a historical adviser on that documentary.) Dully was smart, purposeful and emotionally intact -- everything lobotomy patients aren't supposed to be.

Meeting Dully, you would never guess that when he was 12, a neurologist and psychiatrist named Walter Freeman drove a sharp surgical tool through the thin bone of Dully's eye orbit and into the frontal lobe of his brain, all in a misguided attempt to treat the boy's behavioral problems. The patient survived.

"I'm a bus driver. I'm a husband, and a grandfather," writes Dully, now in his 50s, in the book's opening lines. "I'm into doo-wop music, travel, and photography." He is no vegetable.

As My Lobotomy makes clear, Dully doesn't know if his operation had any physical or mental effect on him. But even if his brain wasn't greatly damaged, he awoke from Freeman's treatment with the sense that something must have been wrong with him to warrant it. His uncertainties led him on a quest to find the reasons for his lobotomy, which fills much of the book. The remainder is an account of his boyhood spent in a troubled California family and his post-lobotomy years in state psychiatric hospitals and schools for juvenile delinquents.

Passages of the book, told in Dully's frank and unvarnished voice, are deeply unsettling. Dully, something of a troublemaker as a boy who had difficulty following the rules in mainstream schools, is locked up in psychiatric wards alongside adults with serious mental disorders.

"There was definitely bad stuff going on around me," Dully writes matter-of-factly. "You'd see guys carted off all the time." But nobody except Freeman -- who saw in the boy symptoms of schizophrenia -- ever diagnosed Dully with a psychiatric illness, so why was he institutionalized, and why was the lobotomy performed?

The blame falls on Dully's stepmother Lou. One of the more loathsome characters you will find in a memoir, she lies to her husband about Dully's transgressions, subjects her stepson to humiliating bathroom and dinner table rituals, and beats Dully on the head with the metal end of a vacuum cleaner hose. Meanwhile, Dully's father fails to defend the boy, who grows increasingly withdrawn and defiant. Lou realizes that her domination will soon end.

"I never raised my hand to her," Dully writes, "and hardly ever raised my voice, but she must have wondered what would happen if I ever fought back. Because I was big, and because she hated me, that must have been a frightening thought."

Lou enlists the medical profession to help her find a long-term solution to the threat she believes her stepson poses. Several psychiatrists suggest that she is the real problem, but she finally finds a sympathetic ear in lobotomy developer and promoter Freeman, who unluckily has set up shop right in the Dullys' hometown. Once Lou spills her story to him, her determination and Freeman's addled medical judgment make the psychosurgery seem inevitable.

Unfortunately, My Lobotomy is not a reliable source of information about Freeman's career and the rise and fall of lobotomy as a mainstream psychiatric treatment. Freeman performed about 3,400 lobotomies, far fewer than the book claims, he never drove a camper that he called a "lobotomobile," and he could legally practice as a psychiatrist in California, to correct a few of the numerous errors.

The value of the book is in the indomitable spirit Dully displays throughout his grueling saga. His descriptions of his recovery from the lobotomy, the deceptions of his stepmother and Freeman, and his response to the photos Freeman compulsively took of his operation are unforgettable. By coming to grips with his past and bravely shining a light into the dark corners of his medical records, Dully shows that regardless of what happened to his brain, his heart and soul are ferociously strong.

Jack El-Hai is the author of The Lobotomist: A Maverick Medical Genius and His Tragic Quest to Rid the World of Mental Illness.

|

Sunday, September 16th 2007, 4:00 AM

Sherryl Connelly

MY

LOBOTOMY

By Howard Dully

Crown,

$24.95

In "My Lobotomy," Howard Dully tells more of the story that so many found gripping in a National Public Radio broadcast: how his stepmother joined with a doctor willing to slice into his brain with "ice picks" when he was all of 12 years old.

Dr. Walter Freeman didn't invent the procedure, but he was a leading proponent of it. When he displayed his handiwork at a professional conference - three lobotomized teenagers, one of them Dully - the other doctors turned on him. Yet he insisted that the risky surgery was an important medical tool. Freeman was certainly eager enough to perform it.

Meanwhile, Dully presents living proof that the lobotomy ruined his life.

"I spent the next four decades in and out of insane asylums, jails and halfway houses," he writes.

Dully was 4, a beloved oldest son, when his mother died. She would be replaced by Lou, a shrew who formed an obsessive dislike of Dully when his father married her. There were four boys in the house, but he was labeled the troublemaker.

It's difficult to discern if Dully was a problem child or not, but from the behavior he describes, it seems attention deficit disorder might be a possibility. Regardless, Lou hated him so much that she invented stories of his violent disposition to tell Freeman.

This Dully found out in the company of an NPR producer and correspondent many decades later, when he began trying to suss out the truth of his story.

By now settled and married, Dully gained access to Freeman's archived papers. Rosemary Kennedy, the President's sister, was a patient. Mildly retarded from birth, at 23 she underwent a lobotomization. She spent nearly 60 years in an institution afterward.

Dully held what may have been the actual picks Freeman used in 1960 to enter his brain through his eye sockets and sever the circuitry. The boy was completely unprepared for what was to take place. He was told he was having tests and actually enjoyed the hospital because he finally got enough to eat.

Though both his stepmother and the doctor were dead when he began his search for answers, Howard was able to confront his father, gently, as to why he would authorize such an appalling procedure.

There was no good answer, but really, how could any answer to a question like that be good enough?

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

'My Lobotomy': Howard Dully's Journey

All Things Considered, November 16, 2005 · On Jan. 17, 1946, a psychiatrist named Walter Freeman launched a radical new era in the treatment of mental illness in this country. On that day, he performed the first-ever transorbital or "ice-pick" lobotomy in his Washington, D.C., office. Freeman believed that mental illness was related to overactive emotions, and that by cutting the brain he cut away these feelings.

Freeman, equal parts physician and showman, became a barnstorming crusader for the procedure. Before his death in 1972, he performed transorbital lobotomies on some 2,500 patients in 23 states.

One of Freeman's youngest patients is today a 56-year-old bus driver living in California. Over the past two years, Howard Dully has embarked on a quest to discover the story behind the procedure he received as a 12-year-old boy.

In researching his story, Dully visited Freeman's son; relatives of patients who underwent the procedure; the archive where Freeman's papers are stored; and Dully's own father, to whom he had never spoken about the lobotomy.

"If you saw me you'd never know I'd had a lobotomy," Dully says. "The only thing you'd notice is that I'm very tall and weigh about 350 pounds. But I've always felt different -- wondered if something's missing from my soul. I have no memory of the operation, and never had the courage to ask my family about it. So two years ago I set out on a journey to learn everything I could about my lobotomy."

Neurologist Egas Moniz performed the first brain surgery to treat mental illness in Portugal in 1935. The procedure, which Moniz called a "leucotomy," involved drilling holes in the patient's skull to get to the brain. Freeman brought the operation to America and gave it a new name: the lobotomy. Freeman and his surgeon partner James Watts performed the first American lobotomy in 1936. Freeman and his lobotomy became famous. But soon he grew impatient.

"My father decided that there must be a better way," says Freeman's son, Frank. Walter Freeman set out to create a new procedure, one that didn't require drilling holes in the head: the transorbital lobotomy. Freeman was convinced that his 10-minute lobotomy was destined to revolutionize medicine. He spent the rest of his life trying to prove his point.

As those who watched the procedure described it, a patient would be rendered unconscious by electroshock. Freeman would then take a sharp ice pick-like instrument, insert it above the patient's eyeball through the orbit of the eye, into the frontal lobes of the brain, moving the instrument back and forth. Then he would do the same thing on the other side of the face.

Freeman performed the procedure for the first time in his Washington, D.C., office on Jan. 17, 1946. His patient was a housewife named Ellen Ionesco. Her daughter, Angelene Forester, was there that day.

"She was absolutely violently suicidal beforehand," Forester says of her mother. "After the transorbital lobotomy there was nothing. It stopped immediately. It was just peace. I don't know how to explain it to you, it was like turning a coin over. That quick. So whatever he did, he did something right."

Ellen Ionesco, now 88 years old, lives in a nursing home in Virginia. "He was just a great man. That's all I can say," she says. But Ionesco says she remembers little about Freeman, including what he looked like.

By 1949, the transorbital lobotomy had caught on. Freeman lobotomized patients in mental institutions across the country.

"There were some very unpleasant results, very tragic results and some excellent results and a lot in between," says Dr. Elliot Valenstein, who wrote Great and Desperate Cures, a book about the history of lobotomies.

Valenstein says the procedure "spread like wildfire" because alternative treatments were scarce. "There was no other way of treating people who were seriously mentally ill," he says. "The drugs weren't introduced until the mid-1950s in the United States, and psychiatric institutions were overcrowded... [Patients and their families] were willing to try almost anything."

By 1950, Freeman's lobotomy revolution was in full swing. Newspapers described it as easier than curing a toothache. Freeman was a showman and liked to shock his audience of doctors and nurses by performing two-handed lobotomies: hammering ice picks into both eyes at once. In 1952, he performed 228 lobotomies in a two-week period in West Virginia alone. (He lobotomized 25 women in a single day.) He decided that his 10-minute lobotomy could be used on others besides the incurably mentally ill.

Anna Ruth Channels suffered from severe headaches and was referred to Freeman in 1950. He prescribed a transorbital lobotomy. The procedure cured Channels of her headaches, but it left her with the mind of a child, according to her daughter, Carol Noelle. "Just as Freeman promised, she didn't worry," Noelle says. "She had no concept of social graces. If someone was having a gathering at their home, she had no problem with going in to their house and taking a seat, too."

Howard Dully's mother died of cancer when he was 5. His father remarried and, Dully says, "My stepmother hated me. I never understood why, but it was clear she'd do anything to get rid of me."

A search of Dully's records among Freeman's files archived at George Washington University turned up clues about why Freeman lobotomized him.

According to Freeman's notes, Lou Dully said she feared her stepson, whom she described as defiant and savage looking. "He doesn't react either to love or to punishment," the notes say of Howard Dully. "He objects to going to bed but then sleeps well. He does a good deal of daydreaming and when asked about it he says 'I don't know.' He turns the room's lights on when there is broad sunlight outside."

On Nov. 30, 1960, Freeman wrote: "Mrs. Dully came in for a talk about Howard. Things have gotten much worse and she can barely endure it. I explained to Mrs. Dully that the family should consider the possibility of changing Howard's personality by means of transorbital lobotomy. Mrs. Dully said it was up to her husband, that I would have to talk with him and make it stick."

Then on Dec. 3, 1960: "Mr. and Mrs. Dully have apparently decided to have Howard operated on. I suggested [they] not tell Howard anything about it."

In an entry dated Jan. 4, 1961, two and a half weeks after the boy's lobotomy, Freeman wrote: "I told Howard what I'd done to him... and he took it without a quiver. He sits quietly, grinning most of the time and offering nothing."

Dully says that when Lou Dully realized the operation didn't turn him "into a vegetable, she got me out of the house. I was made a ward of the state.

"It took me years to get my life together. Through it all I've been haunted by questions: 'Did I do something to deserve this?, Can I ever be normal?', and most of all, 'Why did my dad let this happen?'"

For more than 40 years, Howard Dully had never discussed the lobotomy with his father. In late 2004, Rodney Dully agreed to talk with his son about the operation.

"So how did you find Dr. Freeman?" Howard Dully asks.

"I didn't," Rodney Dully replies, adding that Lou Dully was the one. "She took you... I think she tried some other doctors who said, '...there's nothing wrong here. He's a normal boy.' It was the stepmother problem."

Why would a father let this happen to his son?

"I got manipulated, pure and simple," Rodney Dully says. "I was sold a bill of goods. She sold me and Freeman sold me. And I didn't like it."

The meeting proves cathartic for Howard Dully. "Although he refuses to take any responsibility, just sitting here with my dad and getting to ask him about my lobotomy is the happiest moment of my life," Howard Dully says.

Rebecca Welch's mother Anita was lobotomized by Freeman for postpartum depression in 1953. After spending most of her life in mental institutions, Anita McGee now lives in a nursing home in Birmingham, Ala. Rebecca visits her every week. She believes Walter Freeman's lobotomy destroyed her mother's life.

"I personally think that something in Dr. Freeman wanted to be able to conquer people and take away who they were," Welch says.

At a meeting in the nursing home, Welch and Howard Dully find common ground in their experiences with Freeman. "It does wonders to know that other people have the same pain," Dully says.

Howard Dully's two-year journey in search of the story behind his lobotomy is over. "I'll never know what I lost in those 10 minutes with Dr. Freeman and his ice pick," Dully says. "By some miracle it didn't turn me into a zombie, crush my spirit or kill me. But it did affect me. Deeply. Walter Freeman's operation was supposed to relieve suffering. In my case it did just the opposite. Ever since my lobotomy I've felt like a freak, ashamed."

But now, after meeting with Welch and her mother, Dully says his suffering is over. "I know my lobotomy didn't touch my soul. For the first time I feel no shame. I am, at last, at peace."

After 2,500 operations, Freeman performed his final ice-pick lobotomy on a housewife named Helen Mortenson in February 1967. She died of a brain hemorrhage, and Freeman's career was finally over. Freeman sold his home and spent the rest of his days traveling the country in a camper, visiting old patients, trying desperately to prove that his procedure had transformed thousands of lives for the better. Freeman died of cancer in 1972.

Ver: Manuel Correia, Egas Moniz e a leucotomia pré-frontal: ao largo da polémica in Análise Social, vol. XLI (181), 2006, 1197-1213

Online: http://analisesocial.ics.ul.pt/documentos/1218723826T9yNZ9uf3Rr00MA4.pdf

4-1-2017

Luke Dittrich

A

story of memory, madness, and family secrets

464pp.

Chatto and Windus. £18.99.

978 0 7011 8713 2

On November 19, 1948, the two most enthusiastic and prolific lobotomists in the Western world faced off against each other in the operating theatre at the Institute of Living in Hartford, Connecticut. They performed before an audience of more than two dozen neurosurgeons, neurologists and psychiatrists. Each had developed a different technique for mutilating the brains of the patients they operated on, and each man had his turn on the stage.

William Beecher Scoville, Professor of Neurosurgery at Yale, went first. His patient was conscious. The administration of a local anaesthetic allowed the surgeon to slice through the scalp and peel down the skin from the patient’s forehead, exposing her skull. Quick work with a drill opened two holes, one over each eye. Now Scoville could see her frontal lobes. He levered each side up with a flat blade so that he could perform what he called “orbital undercutting”. What followed was not quite cutting: instead Scoville inserted a suction catheter – a small electrical vacuum cleaner – and sucked out a portion of the patient’s frontal lobes.

The patient was wheeled out and a replacement was secured to the operating table. Walter Freeman was next, a Professor of Neurology from George Washington University. He had no surgical training and no Connecticut medical licence, so he was operating illegally – not that this seemed to bother anyone present. Freeman sought an assembly-line approach so that lobotomy could be performed quickly and easily. His technique allowed him on occasion to perform twenty and more operations in a single day. He proceeded to use shocks from an Electro-Convulsive Therapy machine to render his female patient unconscious, and then inserted an ice pick beneath the eyelid until the point rested on the thin bony structure in the orbit. A few quick taps with a hammer broke through the bone and allowed him to sever portions of the frontal lobes, using a sweeping motion with the ice pick. The instrument was withdrawn and inserted into the other orbit, and within minutes, the process was over. It was, Freeman boasted, so simple an operation that he could teach any fool, even a psychiatrist, to perform it in twenty minutes or so. (The fate of both patients operated on that day was not recorded.)

Tens of thousands of lobotomies were performed in the United States from 1936 onwards, and both these men would continue operating for decades. Lobotomy’s inventor, the Portuguese neurologist Egas Moniz, received the Nobel Prize in Medicine for his pains in 1949. Major medical centres in the United States – Harvard, Yale, Columbia, the University of Pennsylvania – regularly performed variations on the basic operation Freeman and his colleague James Watts first developed in 1936 (which involved drilling through the skull and then blindly severing portions of the frontal lobes with an instrument that resembled a butter knife, something they referred to without irony as a precision lobotomy), well into the 1950s.

It has become fashionable in recent years among some medical historians to argue that the operation was not the medical horror story that popular culture portrays it as being. These scholars suggest that, seen in the context of the times, lobotomy was perhaps a defensible response to massively overcrowded mental hospitals and the therapeutic impotence of the psychiatry of the time. That is not my view, and Luke Dittrich’s book adds to evidence from elsewhere that Scoville, like Freeman, was a monster: ambitious, driven, self-centred and willing to inflict grave and irreversible damage on his patients in his search for fame. He certainly had no time for the Hippocratic injunction, “First, do no harm”.

Ironically, Scoville was quick to denounce the crudity of Freeman’s procedure, a position the neurosurgeons in the audience were happy to endorse. Freeman in turn was scornful of the notion that his rival’s suctioning away of portions of the brain was “precise”, as Scoville and his supporters contended. On these points, at least, both men were correct.

Dittrich devotes considerable space to this remarkable surgical contest in Hartford, one he views with a suitably sceptical eye. But he opens his narrative much earlier, with the story of an accident that befell a young boy of six or seven, Henry Molaison, one summer evening. En route home for dinner, Henry stepped into the street and was struck from behind by a bicycle. The impact threw him through the air, and he landed on his head, sustaining a concussion that temporarily rendered him unconscious. Henry eventually recovered from his injuries, but only partially. He began to suffer epileptic seizures that increased in frequency and severity as the years went by, and made his life a misery. Drugs didn’t help. Finally, in 1953, Henry’s parents brought him to see Dr Scoville. Unlike other patients subjected to psychosurgery, Henry (who was now twenty-six) was sane. Scoville informed the family that the epilepsy might be tamed by the brain surgery he was pioneering, and within a matter of months, Henry was wheeled into the operating theatre. What befell him next made him one of the most famous patients of the twentieth century.

Following his usual procedure, Scoville cut into Henry’s skull, exposing portions of his brain to view. His target on this occasion, however, lay further back, behind the frontal lobes that he usually targeted for his lobotomies. The electroencephalograph had failed to reveal any epileptic focus. Now, using a flat brain spatula, Scoville pushed aside the frontal lobes, exposing deeper structures in the temporal lobe: the amygdala, the uncus, the entorhinal cortex, searching for any obvious defects or atrophied tissue. At this point, a cautious surgeon would have cut the surgery short, since there was no obvious lesion to justify further intervention. Scoville was not such a person. In his own words, “I prefer action to thought, which is why I am a surgeon. I like to see results”. Results he obtained, if not perhaps the ones his patient was hoping for. Using a suction catheter, Scoville proceeded to destroy all three regions of the temporal lobe bilaterally.

Patient H. M., as he became known in the trade, suffered absolutely devastating losses. Though his intellect remained intact, he had in those few minutes lost all but the very shortest of short-term memory. Henceforth, as Scoville noted, he was left essentially helpless and hopeless, with “very grave” memory loss “so severe as to prevent the patient from remembering the location of the rooms in which he lives, the names of his close associates, or even the way to the toilet or the urinal”. And, of course, much else besides: those words constituted, as Dittrich puts it, “the birth announcement of patient H. M. It was also the obituary of Henry Molaison”.

The first of many surprises Dittrich springs on the reader is the news that William Beecher Scoville was his grandfather, someone he came to know well over many years. Those family ties gave him access to all manner of materials that no outsider could have obtained, and he is clearly both a talented and persistent journalist and an excellent storyteller. I found it all the more disappointing, then, that he and his publisher elected to provide no footnotes or any systematic documentation of his sources. What we have is a gripping story, but one whose provenance is at times unfortunately quite murky. A second surprise concerns Dittrich’s grandmother, whom he affectionately refers to as Bam Bam. She had been a high-spirited young woman before she married the handsome Bill Scoville. By 1944, they had three children and Bill was serving in the Army medical corps, leaving her alone much of the time in the small town of Walla Walla in eastern Washington State. Then she found out that her husband was having an affair. She began to hallucinate and later tried to hang herself. She was placed in a secure ward of a local hospital until, a few weeks later, the entire family left for Hartford, Connecticut. Here, she was rushed to the Institute of Living, one of America’s oldest mental hospitals, and the place where her husband would perform most of his lobotomies (though not the operation on H. M.). Scoville had been on the staff there since 1941.

The Institute of Living (previously the Hartford Retreat for the Insane) was a ritzy private establishment catering to the wealthy in surroundings that superficially resembled a country club. Its grounds had been laid out by Frederick Law Olmsted, the architect of Central Park in New York. Its inmates were referred to as “guests”, though these were guests deprived of any voice in their fate. The superintendent, Dr Burlingame, aggressively employed all the latest weapons of 1940s psychiatry: insulin comas, metrazol seizures, hydrotherapy, pyrotherapy (insertion into a coffin-like device that allowed the patient to be heated until the body’s homeostatic mechanism failed and an artificial fever of 105 or 106° Fahrenheit was achieved), and electroshock in its unmodified form (one that produced violent seizures). Bam Bam got many of these to little effect. Her unsympathetic psychiatrist commented that her husband’s infidelity “has upset her to an unusual degree” and her case notes reveal someone frightened of the ECT and still in the grip of psychotic ideation. Her subsequent release seems a bit mysterious. She was henceforth withdrawn and lacking in initiative, a pattern that makes more sense when we learn, in the book’s closing pages, that Dr Scoville had personally lobotomized her. One of the many poignant scenes in Dittrich’s book is his recital of a Thanksgiving dinner at his grandparents’ house, where Bam Bam sat silently amid the family while her now ex-husband and his new wife presided over proceedings.

His book’s title notwithstanding, Dittrich spends much time exposing these family secrets. But he eventually returns to the case of the memory-deprived H. M. Here was a scientific prize. Unlike the legions of lobotomized patients Scoville left in his wake (and he continued to perform his “orbital undercutting” into the 1970s, claiming it was “safe and almost harmless”), H. M. was not mentally ill, and his intellectual abilities remained intact. That made him an ideal subject for research into human memory, and it was the findings from that research that made him so famous (not that Henry was capable of appreciating that). Early on, an eminent neuroscientist from McGill University in Montreal, Dr Brenda Milner, was the primary psychologist studying H. M., and she made a number of path-breaking discoveries about memory from her work with him, including the finding that humans possess two distinct and independent memory systems. One of these had survived in H. M., the one that allowed him to acquire and improve on learned skills. The other, memory for events, was utterly extinguished.

Dr Milner soon moved her research in a different direction and lost touch with H. M. In her place, one of her graduate students, Suzanne Corkin, took over. Subsequently, Corkin obtained a post at MIT. For as long as he lived, Corkin controlled access to him, forcing other researchers who wanted to examine him to comply with her conditions, and building a good deal of her career as one of the first women scientists at MIT, on her privileged access to this fascinating subject. From 1953 until his death in 2008, H. M. was regularly whisked to MIT from the Hartford family he had been placed with, and then the board and care home where he resided to be poked and prodded, examined and re-examined, each time encountering the site and Dr Corkin as though for the first time.

Corkin, it turns out, also had some sort of connection to Dittrich. She had lived directly across the street from the Scoville family and had been Dittrich’s mother’s best friend when they were young – not that it seems to have helped Dittrich much when he sought to interview her for his book. She first avoided meeting him, then sought to put crippling limitations on his ability to use whatever he learned from talking to her. How far this treatment affected his attitude towards her is difficult to say. That he developed an extremely negative view of her behaviour seems unarguable.

As Dittrich points out, Corkin and MIT obtained millions of dollars in research grants from her control over H. M. Not a penny of it reached poor Henry’s pockets. He subsisted on small disability payments from the government, and not once did he receive any compensation for his time and sometimes suffering. He once returned to Hartford, for example, with a series of small second degree burns on his chest – the result of an experiment to determine his pain threshold. After all, he couldn’t remember the experiment, so why not subject him to it? Belatedly, it seems to have occurred to Corkin that she should get some legal authorization for her experiments, since H. M. was manifestly incapable of giving informed consent. Making no effort to locate a living blood relative (a first cousin lived only a few miles away), she instead secured the court-ordered appointment of a conservator who never visited H. M., and who routinely signed off on any proposal she put in front of him.

Henry Molaison does not seem to have had much luck at the hands of those who experimented on him. If Scoville cavalierly made use of him to see what happened when large sections of his brain were suctioned out, Corkin seems to have taken virtual ownership of him and then exploited her good fortune for all it was worth. Nor, according to Dittrich, did these travails end with H. M.’s death. Quickly preserved, his remains were transported back to the West Coast, where a radiologist at the University of California at San Diego carefully harvested his brain and began to reveal its secrets. The Italian-born physician Jacopo Annese comes across as a superb scientist, eager to share what he was finding with the world, but a naïf in shark-infested waters.

As his work proceeded, he discovered an old lesion in H. M.’s frontal lobes, presumably brought about when Scoville manoeuvred them out of the way to reach the deeper structures in the brain he sought to remove. All the memory research on H. M., including Corkin’s work, rested on the assumption that only temporal lobe structures had been damaged, so this was a potentially important finding. Coincidentally or not, after being alerted to this discovery, Corkin called on MIT’s lawyers to reclaim H. M.’s brain and all the photographs and slides Annese had meticulously prepared. Annese had neglected to secure any sort of paper trail documenting his right to these materials. UCSD’s lawyers hung him out to dry. Waving a document she had secured from the court-appointed guardian she had personally nominated, Corkin and MIT’s attorneys successfully reclaimed the lot. Annese promptly resigned his faculty appointment, his research career in tatters and his slides and photographs taken from him. Along with H. M.’s brain, MIT insisted that they should be transported to a different University of California campus at Davis, an odd move since Annese had explicitly promised to share all his findings freely with others and had begun to do so. Acccording to Dittrich, Corkin then added one final twist of the knife. In an interview with him before she died of liver cancer in May of this year, she announced that she planned to shred all her raw materials and the laboratory records relating to her work with Henry Molaison, and that she had already shredded many of them. For the last fifty years of his life, she had essentially owned H. M. Now she planned to carry with her to her grave whatever secrets lay hidden in her files.