Balthus was also admired as a stage designer for

Shakespeare's "As You Like It," Shelley's "Cenci" (as adapted by Artaud), Albert

Camus's "État de Siège" and Mozart's "Così Fan Tutte."

In Emily Brontë's "Wuthering Heights," he found

inspiration in 1934 and '35 for a long series of drawings, more than one of

which rivaled the singular mood of Brontë herself in its portrayal of a frenetic

wooing between young people.

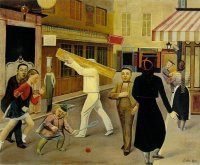

But above all, Balthus was known for paintings of

equivocal figure subjects, very young women in poses or situations that were

regarded as enigmatic or suggestive or both. Often these subjects were caught

between dream and waking. Sometimes there were more explicitly sexual elements,

and these caused a minor scandal as early as 1934, when he had his first one-man

show at the Galerie Pierre in Paris.

Though never wholly discarded, the element of erotic

provocation became more oblique in his later work. ("I used to want to shock,"

he once told a friend, "but now it bores me.") In 1955, he even agreed to tone

down an erotic incident in "The Street" (1933), a painting that had been bought

by James Thrall Soby, one of his earliest American admirers, who later

bequeathed it to the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.

"I really don't understand why people see the paintings

of girls as Lolitas," he told the chief art critic of The New York Times,

Michael Kimmelman, in 1996. "My little model is absolutely untouchable to me.

Some American journalist said he found my work pornographic. What does he mean?

Everything now is pornographic. Advertising is pornographic. You see a young

woman putting on some beauty product who looks like she's having an orgasm. I've

never made anything pornographic. Except perhaps `The Guitar Lesson.' "

That large painting, exhibited in the 1934 show at the

Galerie Pierre, depicts a girl naked below the waist and slumped over the knees

of a bare-breasted woman, who evidently is her teacher. A guitar is on the floor

and a piano is in the background. But the figure of the girl, it has been

pointed out, most directly echoes the dead Christ in the 15th-century Avignon

Pietà in the Louvre; it's a link, it has been argued, that by its blasphemy

heightens the shock.

"I absolutely never thought of that, never," Balthus

protested in the 1996 interview. "I'm Catholic. I'm a member of the Order of St.

Maurice and St. Lazare!"

Among painters, poets, novelists, theater people and

fashionable hostesses in Paris, Balthus never ceased to be admired as an artist

and sought out as a companion. But after the scandal of 1934 he did not have

another exhibition in Paris until after World War II.

From his school days onward, Balthus was drawn to the

apple-green uplands of the Bernese Oberland. That fascination found apotheosis

in 1937 in the large painting "The Mountain," which is now at the Metropolitan

Museum of Art. Against a jagged and rocky backdrop, three young people, locked

in daydreams of their own devising, act out their notions of what life may have

in store for them.

It was not in Paris but in New York, at the Pierre

Matisse Gallery in 1938, that Balthus showed his work in great strength and

began to be sought after by American collectors and museums. From 1938 to 1977,

his eight exhibitions at the gallery were major events in the New York art

world, as were his exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1956 and the major

retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1984.

Balthus never came to the United States, and for most

of his life he lived either in Paris or in a succession of increasingly grand

and often remote country houses in France, Switzerland and Italy. Even in Paris,

he loved an august association and lived in a house in the Cour de Rohan that

was once described as "carved out of the huge vine-clad masonry of

Philippe-Auguste's fortifications."

A house that suited him very well was the Château de

Chassy, in the mountainous Morvan region in east-central France, where he lived

from 1953 onward. In the paintings of that period, he brought a contemplative

majesty to both outdoor and indoor life. There is in the big Chassy landscapes

something of the four "Seasons" (in the Louvre) in which Poussin commemorated

the rightness of nature and the presence in all natural things of a predestined

order.

Balthus's basically reclusive way of life was

transformed in 1961, when at the invitation of André Malraux, then France's

minister of culture, he became director of the French Academy in Rome.

Among his predecessors in the post were Ingres and

Berlioz. One of the great European town houses, the Villa Medici, went with the

job. The architecture had Michelangelesque echoes, but the interior had badly

deteriorated over generations of institutional use. During his 16 years of

residence, Balthus restored an uncluttered nobility to the interior and made the

18-acre gardens look as they did when Velázquez painted them.

In these restorations, almost as much as in the

paintings on which he was working at the same time, a creativity peculiar to

himself was at work.

It was in the hallowed studios in the gardens of the

Villa Medici that Balthus worked with a new medium (casein tempera on canvas) to

produce the series of endlessly worked and reworked figure paintings that won

him a whole new reputation. Many of them featured a young Japanese woman,

Setusuko Ideta, whom he had met in Japan in 1962 and wed in 1967 after his first

marriage had ended in divorce. He would work on some of these paintings for 6, 7

or even 10 years.

Sometimes he would speak of them as "utter failures,

without exception" that had been not so much "finished" as given up in despair.

But like his friend the sculptor and painter Alberto Giacometti, he disliked the

very notion of "finish" in art.

After leaving Rome in 1977, Balthus, his wife and their

daughter, Harumi, settled in a chalet near Gstaad. He is survived by his wife

and daughter; two sons, Stanislas and Thaddeus, from his first marriage; and a

brother, Pierre Klossowski, a painter and writer.

At a time when the School of Paris was generally

thought to be in decline, Balthus kept his position as a major European artist.

Full-scale retrospectives were held at the Musée des Arts Decoratifs in Paris in

1966, at the Tate Gallery in London in 1968, at the Venice Biennale in 1980 and

at the Spoleto Festival in Italy in 1982. After his work was exhibited in "A New

Spirit in Painting" at the Royal Academy in London 1981, Balthus was invited to

become a foreign member of the Academy. He had a major museum retrospective in

Lausanne in 1993 and a lesser but significant exhibition of his drawings in Bern

in 1994.

Balthasar Klossowski was the second son of Erich

Klossowski, a Polish-born art historian, painter and stage designer, and his

wife, Elisabeth Dorothea Spiro, a painter who exhibited under the name Baladine.

For political reasons, his family had left Poland in 1830 and eventually settled

in Breslau, acquiring German citizenship there.

Balthus's father made a name for himself in each of his

activities, especially as the author of a comprehensive study of the work of

Honoré Daumier. His maternal grandfather was a cantor in Breslau and composed a

great deal of music for religious services.

In 1903 the family moved to Paris, mixing freely and

happily in the worlds of painting, scholarship, poetry, theater and publishing

there. Balthus was born on Feb. 29, 1908. The poet Rainer Maria Rilke once told

him that being born on leap day was like slipping through a crack in time; it

gave Balthus access to "a kingdom independent of all the changes we undergo."

At the outbreak of World War I, the Klossowskis' status

as enemy aliens caused them to move to Berlin, where they lived in straitened

circumstances. As of 1917, Balthus's parents lived apart, and Balthus moved to

Switzerland with his mother. They had a tiny apartment in Geneva, and Balthus

spent summers above the Lake of Thun in a landscape to which he always returned

with great pleasure.

In 1919, Balthus's mother was befriended by Rilke, the

foremost German poet of the day. Until his death in 1926, Rilke had an intense

and continuous relationship with her and her two sons. In 1921, Rilke wrote a

French text for the publication of "Mitsou," a book of 40 ink drawings by the

13-year-old Balthus on the subject of a solitary boyhood. In its way a trial run

for ideas that were to haunt Balthus's work for many years, the little book was

described by the eminent German publisher Kurt Wolff as "astounding and almost

frightening."

It was also thanks largely to Rilke that when Balthus

went to Paris at the age of 16 in 1924, many doors were open to him. He was

welcomed by André Gide, the most influential writer of the day, and by Pierre

Bonnard, Albert Marquet and Maurice Denis among painters. When Rilke came to

Paris for five months in 1925, he dedicated his new poem, "Narcisse," to Balthus.

In 1926, with financial help from Rilke, Balthus spent a year traveling in Italy,

where he made copies and sketches after Piero della Francesca, Masaccio,

Masolino and others.

Thereafter he spent much of his time in Paris, where he

became friendly with Braque, Derain and Giacometti among artists, with Pierre

Jean Jouve, Malraux and Paul Éluard among writers, and with Jean-Louis Barrault,

Madeleine Renaud and others in the theater.

Balthus married Antoinette de Watteville in Bern in

1937. In 1939, he was called up for service in the French Army and served near

Saarbrücken before being discharged in December 1939. After the collapse of

France to German forces, he and his wife lived on a farm in the French Savoie

until 1942, when they moved to Switzerland and lived for some time in Fribourg.

While waiting to return to Paris at war's end, Balthus

lived for some time in the Villa Diodati, near Geneva, where Lord Byron had once

lived. Balthus liked to fantasize about a supposed family connection between

himself and Byron.

After the death of his father in 1949 and of his mother

in 1969, Balthus took advantage of what he believed to be his ancient and noble

Polish lineage and asked to be called the Comte de Rola.

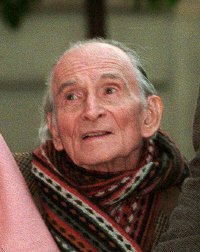

Despite a lifelong horror of being photographed or

interviewed, he became more accessible in his later years, though still deeply

concerned with his privacy. He once said about himself, "Balthus is a painter

about whom nothing is known." The often-quoted statement implied that whatever

people thought they knew about him or his work was wrong.