2-1-2002

ANDY WARHOL

6/8/1928 -

22/2/1987

| |

Andy Warhol began as a commercial illustrator, and a very successful one,

doing jobs like shoe ads for I. Miller in a stylish blotty line that derived

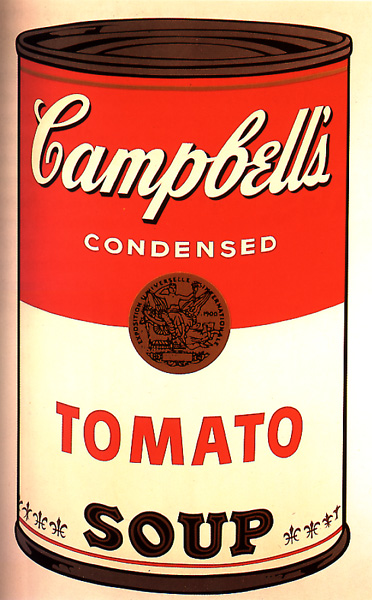

from Ben Shahn. He first exhibited in an art gallery in 1962, when the Ferus

Gallery in Los Angeles showed his 32

Campbell's Soup Cans,

1961-62. From then on, most of Warhol's best work was done over a span of

about six years, finishing in 1968, when he was shot. And it all flowed from

one central insight: that in a culture glutted with information, where most

people experience most things at second or third hand through TV and print,

through images that become banal and disassociated by repeated again and

again and again, there is role for affectless art. You no longer need to be

hot and full of feeling. You can be supercool, like a slightly frosted

mirror. Not that Warhol worked this out; he didn't have to. He felt it and

embodied it. He was a conduit for a sort of collective American state of

mind in which celebrity - the famous image of a person, the famous brand

name - had completely replaced both sacredness and solidity.

|

|

Earlier artists, like

Monet,

had painted the same motif in series in order to display minute discriminations

of perception, the shift of light and color form hour to hour on a haystack, and

how these could be recorded by the subtlety of eye and hand. Warhol's thirty-two

soup cans are about nothing of the kind. They are about sameness (though with

different labels): same brand, same size, same paint surface, same fame as

product. They mimic the condition of mass advertising, out of which his

sensibility had grown. They are much more deadpan than the object which may have

partly inspired them, Jasper Johns's pair of bronze Ballantine ale cans. This

affectlessness, this fascinated and yet indifferent take on the object, became

the key to Warhol's work; it is there in the repetition of stars' faces (Liz,

Jackie, Marilyn, Marlon, and the rest), and as a record of the condition of

being an uninvolved spectator it speaks eloquently about the condition of image

overload in a media saturated culture. Warhol extended it by using silk screen,

and not bothering to clean up the imperfections of the print: those slips of the

screen, uneven inkings of the roller, and general graininess. What they

suggested was not the humanizing touch of the hand but the pervasiveness of

routine error and of entropy..."

- From

"American Visions", by Robert Hughes

Andy

Warhol

By Wayne

Koestenbaum

Viking Press

224 pages

Penguin Lives

From

www.salon.com

The opposite

of sex

Andy Warhol,

ultimate icon of pop, made painting an orgy and pornography an art form. But

you'll never guess what he did between the sheets.

- - - - - -

- - - - - -

By Jonathon Keats

| |

|

|

Sept. 28,

2001 | The public grade school in my neighborhood, like so many

around the country, is a preposterous edifice of neoclassical posturing,

with a miscellany of famous names inscribed across its facade. Neither

arbitrary nor encyclopedic, the list seems to me the lasting trace of a

spectacularly capricious selection process. Homer and Galileo and Comte.

Pericles and Shakespeare. Pasteur and Moses and Wagner. About the only thing

the names have in common is that each overshadows the accomplishments of the

man it marks. They are names we know before we know why we know them, and

better than we'll ever know the people for whom they once stood: Galileo and

Homer are our cultural icons on account of their obliging anonymity, our

idols because they embody whatever we desire.

Andy Warhol also had that. He made himself a name, and vanished in our

midst. That was his art. Pity anybody who undertakes his biography: Whatever

one claims is questionable, and to catch him whole is less feasible, even,

than dismissing him out of hand.

Wayne Koestenbaum, English professor and cultural commentator, has made

an arresting attempt. His new book -- part of the Penguin Lives series

profiling such edifice icons as the Buddha, Mozart and Joan of Arc -- is an

important study in ambivalent sexual identity. Whether "Andy Warhol" truly

depicts Andy Warhol is irrelevant, a point with which I have to assume

Koestenbaum would agree: Over the decade I've been entranced by Warhol,

greatest artist of the late 20th century, and I've read only perhaps half

the sources in Koestenbaum's eight-page bibliography, yet even I can

appreciate the skill with which he's navigated contradictory accounts to

find for his biography a set of facts convenient to his own vision of male

sexuality.

|

| |

The great glory of Warhol is that,

even more than with Moses or Mozart, you can believe anything, and find a

wealth of material to complicate your theory into a self-sustaining object

of study. He is a blank-check metaphor to be spent time and again. The only

trouble comes if you try to cash in, mistake hypothetical for history. As

Koestenbaum vividly illustrates in his compellingly irrelevant account, even

the best and brightest writers are susceptible to that slip into the Warhol

abyss.

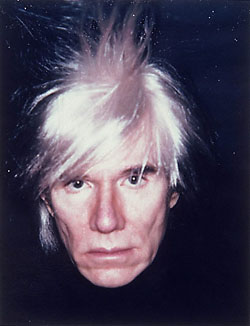

Koestenbaum's discourse on gay sex in the '60s

through the '80s stars Andy Warhol as ugly duckling, and certainly there's

ample physical evidence to support such casting: Before the age of 30,

Warhol wore a wig and had been to a surgeon to sand down his bulbous red

nose. Combine that with the neurological damage done by chorea while he was

still a child -- he was hypersensitive to touch for the rest of his life --

and the deep divide between his public fame and his intense privacy, and you

have all it takes to make up a fascinating sexual profile, especially

against a backdrop as free of inhibition as the studio Warhol called his

"Factory," in a world as repressed as America before Stonewall. |

|

|

Naturally, every kink only adds

interest. As Koestenbaum's inquiry falls into the throes of sex, he finds that,

"For Warhol, everything is sexual. Stillness is sexual. Looking and being looked

at are sexual. Time is sexual: that is why it must be stopped. Warhol's art was

the sexualized body his actual body largely refused to be."

Warhol seems to have been

amenable to people thinking of him like that. Speaking to one of his '60s

superstars about some of the comic book characters who were the subject of his

first pop paintings, he claimed that they'd been his sex idols as a child: "My

mother caught me one day playing with myself and looking at a Popeye cartoon,"

he confessed.

If we take him at his word,

never advisable in his case, that makes those innocuous images consistent with

the sexually explicit scenarios characteristic of his films (aptly titled "Blow

Job" for example, or "Taylor Mead's Ass") and the paintings made late in his

life by ejaculating onto canvas.

Look for

erotic charge in Warhol's art, and you probably won't be disappointed. In his

movies alone, there's enough variety to satisfy just about every taste. My

hopelessly heterosexual appetite inclines me toward debutante manqué Edie

Sedgwick, whom Koestenbaum perfectly describes as "hypnotized by her own

gestural carnival," but there's also ample footage of Gerard Malanga, depicted

by Koestenbaum as "a beat Beau Brummel," and even of the Puerto Rican post

office worker turned drag queen Maria Montez.

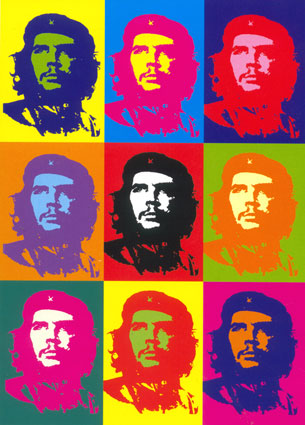

Warhol also made silk-screens

of subjects perhaps more physically enticing than those early pictures of

Popeye. That Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley were sex idols clear across

American culture goes without saying, and his images of each capture them at the

prime of their glamour. The series he titled "Torsos" is more explicit,

silk-screens made from Warhol's Polaroids of male and female genitalia, and

pictures like "Silver Car Crash" may just qualify as pornography within the J.G.

Ballard set. But Koestenbaum is after something more, something different.

Perhaps taking his cue from Warhol, who liked to call sex abstract, he gives the

following sexual exegesis on Andy's notorious Campbell's Soup silk-screens:

"Displacement and other

metaphoric processes contributed to his choice of Campbell soup as subject, and

connected the image to his erotic hungers. Indeed, cans, in Warhol's work,

continue the task of [his earlier] 'cock drawings,' for cans allude to the

sexual body, and to limbs iconically isolated from the whole: as a ... penis (in

his 'cock drawings') is featured in relative isolation from face and torso, so

the can is alienated from the act of eating that it nonetheless announces as a

purchasable possibility. The can's most arresting word -- the eye ignores it for

the first hundred times -- is condensed: 'Campbell's Condensed.' Condensation is

a property of dreams and the unconscious; the soup-can fetish condenses Andy's

unspeakable interior procedures, and gives them a shopwindow's attractiveness."

Even ignoring the obvious

implausibility of Koestenbaum's claim, we must consider the more tenuous

assumption from which it arises: Rather than taking Warhol's life and art as two

faces of an interesting fiction, he imagines that we can understand Andy's life

by deciphering his art, as if Warhol were an Enigma Machine systematically

encoding some known quantity. Certainly those soup cans are loaded with

metaphoric potential. So are Warhol's films, and the stories swarming his life.

Yet Koestenbaum, like so many of Warhol's would-be biographers, confuses

metaphor for fact, a mistake as great as assuming that an accurate nautical map

spread smooth on a table proves that the world is flat.

- - - - - -

- - - - - -

Echoing the estimable art

critic Arthur Danto, Koestenbaum says that Warhol was a philosopher. "He used

his art to think through problems of space, time, and embodiment, and the center

of his metaphysical investigations was the aroused or indifferent body ..." I

must disagree: Andy Warhol wasn't a philosopher. He was, and remains, a

philosophy.

What I mean is that he

interests us not as a commentator but as the object of ever inconclusive

commentary, not as an investigator but as the scene of a perfect crime. This may

seem odd, as he's popularly perceived as a voyeur, the man who routinely asked

strangers to drop their pants, never went anywhere without a tape recorder (an

accessory he suggestively called his wife). But all that was part of his act,

facets of the life that was his art. While I don't doubt that Warhol knew what

he was up to with his naïveté, by now I also know better than to quibble:

Dismiss Andy's act and you've missed his art, but indulge his naïveté by

emulating it, and you start truly to appreciate his work.

Koestenbaum wants to believe

that Warhol explored the problems of philosophy as if his Factory were his

laboratory, as if each artwork were an experiment with which he came to

metaphysical conclusions presented for our edification, concealed in an

iconography of Leonardo-like sophistication. What he actually did was less

complicated but more difficult: In his life, he embodied ideas worthy of

laboratory study.

We're told that Warhol once had

another man in powdered hair impersonate him on a college lecture tour, and also

that he wished he could be replaced by a robot. We're told that he had his

mother sign his name to his drawings, that he had studio assistants pull his

silk-screens, and acquaintances inseminate his ejaculation paintings. We're told

that he routinely asked people what he should paint, and some of his best

subjects, including soup cans, were suggested by others. We're told that he may

have authorized Malanga, that beat Beau Brummel, to run off fraudulent Warhols

in Europe. We're told that Andy authored his only novel by first pursuing his

speed-freak groupies with a tape recorder for 24 hours and then insisting that

his publisher print the typescript, an erratic document produced in Factory

off-hours by various nameless studio squatters, without any copy-editing

whatsoever.

Elsewhere we're told that same

story, except that Warhol hired a professional typing service to make the

transcript. I prefer the first version, not because it comes from a more

credible source but because it involves more accomplices, another chancy element

along the ever-unaccountable Warhol assembly line.

Chancier and chancier. I can

choose the story I find more suitable, the one that opens more questions,

because the Factory systematically overwrote any attempt at one official story.

So we're told not only that Warhol hired an impersonator on the college lecture

circuit but also that he expected anybody who answered the Factory telephone to

be Andy on his behalf. That was especially important when Warhol was called by

interviewers: Even the lies they were told weren't Andy's own. Astoundingly, he

seems to have accelerated history: It's taken centuries for us to become as

unsure about Shakespeare as we are of Warhol. He could become an icon in his own

lifetime because even as we saw him with our own eyes, at a flea market, say, or

at a party with Bianca Jagger and Halston, we couldn't even begin to agree with

one another who he really was, couldn't be sure that anybody, even he, knew the

truth.

I should

confess that, like Koestenbaum, I never met Warhol. He died in 1987, which was

my freshman year in high school. My serious interest didn't begin until college,

brought on by conversations that wouldn't end, contradictions that couldn't be

resolved. Once I started to see, there was no natural place to stop.

There is too much Warhol. He

boasted that in a single year he could produce as many paintings as Picasso did

in a lifetime. He shot so much footage that some of his films still haven't been

screened, and others, such as his masterly eight-hour image of an absolutely

stationary Empire State Building, challenge the attention span of even the most

ardent fan. (Another Warhol story, absolutely unverified, tells of the time a

few film students kidnapped Andy, chained him to a seat in an abandoned theater,

and started "Empire" on the projector. By the time they returned to run the

second reel, he'd escaped, vanished without a trace.)

Too, too much. Beyond what we

ordinarily call Andy's art, there are multiple ghostwritten books, all those

cookie jars that cluttered his house. There are his time capsules, boxes filled

with each month's junk, now housed en masse at the colossal Andy Warhol Museum.

Koestenbaum starts to catalog one, in which he finds: "porn, fashion magazines,

Natalie Wood publicity photos, a newspaper with a picture of John F. Kennedy Jr.,

a copy of Kenneth Anger's 'Hollywood Babylon,' invitations from Warhol's 1957

Golden Pictures show at the Bodley Gallery, bills, issues of Life and The New

Yorker, a piece of blank canvas, a letter from Gerard Malanga ..."

I can think of only one case of

a collection that comes close in scope: The dymaxion (a word he coined made from

"dynamic" and "maximum") remains of R. Buckminster Fuller now occupy some 1,500

linear feet of shelf space in a controlled-climate storage facility near

Stanford University. Still, the Fuller files are the product of an opposite

inclination. Bucky, who called himself Guineapig B, preserved every lecture,

letter, sketch and dry cleaning receipt in perfect chronological order, indexed

as meticulously as Diderot's Encyclopédie, to provide history with a single

perfect record of a life lived across the 20th century.

In life he attempted to be

exemplary, a renaissance everyman, that he might leave a paper trail as

universal as it was comprehensive. Of course his project failed: The volume of

information precluded comprehension. The range of thought blew the mind. Bucky

Fuller became a cultural icon as the amount we knew about him was overwhelmed by

the amount we knew we'd never know.

With Warhol, we don't even have

the pretense of comprehension. No Guineapig B, he sometimes called himself Andy

Paperbag. The name evokes not experience, but accumulation. As an icon, he out-Buckminstered

Fuller in half the lifetime. The boxes just piled up. The parties with Bianca

Jagger and Halston bloated his oral diaries. The flea market finds filled his

townhouse to warehouse capacity. Ever afraid of death, Warhol buried himself

ahead of his years, preserved a little like Pompeii, and now we have all the

ambiguity of excavation, the wear of history, intangible antiquity.

We cannot touch Shakespeare or

Joan of Arc. Their names are but a façade. We know them by degrees of

separation, as hypersensitive Andy held people off with the freak show of his

ugly duckling body. No matter who the man in the white wig slept with, the

artist Andy Warhol, the icon that is the face of his artwork, is asexual to the

degree that he is ahistorical, ahistorical to the extent that he's immortal. We

shouldn't be surprised that, shackled into viewing his own moving picture,

Warhol slipped right out of the theater.

He had no body, no substance to

hold him still. His whole life was a vanishing act, dramatic because the ballast

he appeared to add -- the fame, the paintings, the junk -- paradoxically reduced

what remained of Andy Paperbag to the iconic shorthand, the laboratory purity,

of a Guineapig A. The mystery, how he did it, is the impossible philosophical

conundrum he created, the artwork of his lifetime that so aboundingly confounds

Koestenbaum, Danto, me.

Maybe the man in the white wig

was also a little curious about Andy Warhol. Maybe he was even a philosopher, a

man with insight of his own. If so, I'd like to believe he left us a message: In

1985, a New York nightclub called Area briefly showed an Andy Warhol original

called "Invisible Sculpture." On a pedestal against a wall, Warhol momentarily

stood beside a label bearing the artist's name. Then the man in the white wig

walked away.

About the writer

Jonathon Keats is the author of the novel "The

Pathology of Lies." He is currently at work on a novel about a plagiarist.

Pop goes the Pop-art cliché

By SARAH MILROY

Saturday, December 8, 2001

Andy Warhol

By Wayne Koestenbaum

Viking, 224 pages, $31.99

| |

One could be forgiven for

thinking there was not a lot more to say about Andy Warhol, the American Pop

legend who perfected the art of playing dead (a cadaverous human specimen,

he made human emotion seem impossibly passé), and has engendered, before and

certainly after his death in 1987, a veritable tonnage of critical

commentary and biographical exegesis.

Yet Andy will not die.

Wayne Koestenbaum, a U.S. critic and academic whose best-known previous work

was a cultural study of the iconic Jacqueline Kennedy, has taken on another

equally enigmatic legend here, coming up with a barrel-load of fresh

insights into the artist's psychological motivations and quirks, and

arriving at some provocative conclusions.

The author's most attractive attribute is his devotion to his subject; the

book radiates a deeply intelligent attachment, filled with compassion,

humour and sensitivity. One has the impression that Koestenbaum has

obsessively burrowed away into the psyche of the artist, gallantly refusing

Warhol's self-designation as a man without ideas or feelings, and producing

many deeply melancholy passages of writing that deliver the flavour of this

lonely, brilliant misfit. ("Being born," Warhol quipped, "is like being

kidnapped. And then sold into slavery.") Instead of a bland overview,

Koestenbaum has produced an account of the artist too dense, in fact, to be

consumed at a gallop. The reader gets the sense that deep in the heart of

this slim, 224-page biography is a fat, five-volume tome, just screaming to

get out. |

|

|

It is perhaps due to this act

of compression that the book fails to attend in a conventional way to the hills

and valleys of the career. While Koestenbaum does not require that the reader

have a thorough grounding in Warholia, a reader without such a grounding might,

for example, come away without a sense of when Warhol's career peaked in the

public eye -- with the soup cans and the Marilyns and Lizes and Jackies -- or

why those images were felt to be so important. The whole question of his

relationship to the media and its role in society, for example, is barely

touched on.

Instead, we hear at length

about the metaphorical implications of his mother's colostomy bag (which

underlies, the author says, the artist's lifelong impulse to represent cultural

waste products), about his Brillo boxes as surrogates for bodily orifices ("To

Open: Press Down/Pull Up" read the directions on one such work), and the

artist's deep-seated dread of his own physical self. "These boxes without

openings," Koestenbaum writes, "seem simulacra of Andy's body -- a queer body

that may want to be entered or to enter, but that offers too many feints, too

many surfaces, too much braggadocio, and no real opening." It's an eccentric,

but fascinating, view.

Andy Warhol

is propelled by several implicit mandates. First, Koestenbaum comes out swinging

on the subject of Warhol's sexuality. He asks in the first pages: How gay is

Warhol? As gay as gay can be. Sex, Koestenbaum writes, lay at the root of his

every inspiration. "Warhol didn't sublimate sex," he writes, "he simply extended

its jurisdiction, allowing it to dominate every process and pastime. For Warhol,

everything is sexual. Contemplation is sexual. Movement is sexual. Stillness is

sexual. Looking and being looked at are sexual."

We are treated to several

accounts of the artist in flagrante delicto,or in tenacious coital

pursuit (often rebuffed) -- deep-sixing forever the notion of Warhol as asexual

(a notion the author ascribes to the critics' uneasiness with homosexuality).

But more often we see him watching sex, and running from the room to have "an

organza" -- a delightful malapropism he coined to describe the moment of erotic

abandon. True, it's hard to think of a man who lived with his mother throughout

his adult life, and subsisted almost exclusively on canned soup (Campbell's of

course), as a sexual maverick, but in Koestenbaum's view, Warhol was equipped

with two more sexual orifices (or protrusions) than the rest of us: his eyes.

Second, the book attempts to

retrieve the films from the also-ran status often afforded them in critical

appraisals, taking us through them with an almost exhaustive blow-by-blow

description -- if you'll pardon the expression. We learn more than we perhaps

need to know about the various denizens of the Factory, and the actions that

form the "plots" of Warhol's oddly hypnotic movies. So and so fellates such and

such. Such and such rolls over and shoots up. Someone is watched urinating in

the bathroom, while another takes a shower.

The languor of Koestenbaum's

descriptions echo the hypnotic quality of the films themselves -- the most

famous of which remain the Screen Tests (begun in 1964), Chelsea Girls

(1966), Vinyl (1965), Sleep (1963) and Blow Job (1964)

-- and he digs deep into the films' undercurrent of "torture," the consistent

psychological duress visited on the participants. For all that his discussions

of the films can stretch interminably, like the films themselves, his analysis

without question leads us to think more deeply about the films, and helps us to

recognize them for what they are: beachheads in the battle to represent male

homoerotic desire, and revolutionary precursors to "reality TV."

Third, Koestenbaum makes a

strong play to rescue Warhol's late work from the art-critical Elba to which it

has characteristically been banished. He endorses, by turns, the late society

portraits (in all their pandering proliferation), the Endangered Species series

and the Queens series -- describing their continuity with Warhol's earlier work

and their consistency with the themes that dominated his life. (In the case of

the Endangered Species prints, he writes, we can read Warhol's sense of

existential frailty following his shooting by deranged Factory groupie Valerie

Solanis in 1968, as well as the looming threat of AIDS. In the

Queens, we find reflected his lifelong yearning to be one.)

Yet while these works appear

much more interesting contextualised by Koestenbaum in this way, their imagery

alone can't make them great art. It just makes them psychologically legible.

Warhol, as he made clear in his diaries, thought they were crap, and this may be

a case of Andy knows best. Still, one has to admire Koestenbaum's valiant

defence. Like much in this book, the position strikes one as slightly perverse,

but one is much the better for following Koestenbaum in his passionate and

highly informed digression from received ideas.

Sarah Milroy is The Globe and Mail's visual arts

critic.

South Florida

Sun-Sentinel

Warhol: A scholarly

pretension

By Steven E. Alford

Special Correspondent

Posted

October 28 2001

Andy

Warhol. Wayne Koestenbaum. Lipper/Viking. 224 pp.

| |

Click

to enlarge |

|

Somebody should tell Michael Jackson: the King of Pop

has been--and will be--Andy Warhol. Wayne Koestenbaum's biography tells the

story of this "mixture of Picasso and Henry Ford," but in so doing, buries

him beneath unsubstantiated interpretative speculation about the "meaning"

of Warhol's work.

Andrew Warhola was born in 1928, the third of three boys. The most

significant event of his childhood was contracting St. Vitus' Dance, or

chorea, which struck him when he was 8. At 13, his father died, and he

maintained an unusually close relationship with his mother for virtually the

rest of her life. |

Andy attended Carnegie Tech, majoring in pictorial design.

After flunking out the first year, he was readmitted as an "eccentric talent."

Graduating in 1949, he moved from

Pittsburgh to New York, where

he found work in advertising. The link, or canyon, between art and commerce was

to be a feature of his career.

He first showed his paintings in a Bonwit Teller window in 1961, and had his

first gallery show in 1962.

Koestenbaum offers some valuable insights. "Warhol's game, throughout his

career, was to transpose sensation from one medium into another--to turn a

photograph into a painting by silkscreening it; to transform a movie into a

sculpture by filming motionless objects and individuals; to transcribe

tape-recorded speech into a novel."

Koestenbaum passes over the story of his painterly career, claiming that it has

been often told, and concentrates for the greater part of the book on Warhol's

films. For anyone who has seen a Warhol film, this decision is sure to incite

uneasiness.

The reader is tipped off that there may be a problem: "Watching dozens of hours

of these early Warhol films in which little or nothing happens, I couldn't take

my eyes off the screen, lest I miss something important."

Koestenbaum's oracular pronouncements sometimes transcend the merely odd,

aspiring to absolute zaniness. "Each canvas asks: Do you desire me? Will you

destroy me? Will you participate in my ritual? Each image, while hoping to repel

death, engineers its erotic arrival." Huh?

Koestenbaum comments on one of the deliberately tedious sequences from an early

Warhol film, in which he describes drag queen Mario Montez's slow movements as

"a tempo that a stern skeptic might call narcissistic self-absorption but that

I, more charitably, if portentously, would call an investigation of the schisms

that make up presence." Memo to drag queens: you're not vain; you're a

Heideggerian.

My favorite Koestenbaum mot, from a film with an unprintable title: "The

buttocks, seen in isolation, seem explicitly double: two cheeks, divided in the

center by a dark line."

Warhol's persona was famously blank; as art historian Robert Rosenblum said,

Warhol had "no human affect." Hence, scholars can feel free to paint

interpretations on the banality and the silence that characterized his public

presentation. But just a little of this been-inside-too-long scholarship goes a

long way.

Shot by Valeria Solanas, dead at 58 from nursing incompetence after a

gall-bladder operation, the highlights of Warhol's life are touched on, but

given little notice by Koestenbaum relative to the space he spends on his films.

This is the kind of book that will make no one happy. It is scholarly in tone,

yet displaying high-flying speculation absent any evidence. It is gossipy, but

gossipy about inarticulate druggies whose expressiveness consists in allowing

Andy to film them having sex. Koestenbaum repeatedly makes murky aesthetic

judgments about Warhol's work, and then qualifies them out of existence. This

slim volume adds little to our understanding of an artist whose personal goals

were to become "vacant" and "vacuous."

Steven E. Alford is a professor of the humanities at Nova

Southeastern University.

ART news ONLINE

January 2002

Much More Than Fifteen Minutes

Fifteen years after his death, Andy Warhol’s reputation is soaring again.

Collectors are paying record prices for his works, exhibitions are touring the

globe, and a commemorative postage stamp is in the works

By Tyler Maroney

At Sotheby’s contemporary-art auction in London last June,

prices were high and house records were broken. Gerhard Richter set an auction

record for his color charts when 180 Colors sold for $2.9 million. But

the highlight of the evening was Lot 17, a pink acrylic-and-silk-screen print

called Little Electric Chair by Andy Warhol. Sotheby’s main saleroom on

New Bond Street was standing-room-only that evening. When the bidding for

Little Electric Chair began, it was heavy and furious, but when the bids

climbed above the $1.5 million mark, the room fell silent. The three remaining

bidders—none present and all anonymous—relayed their bids via representatives on

cell phones. The sale catalogue lists the estimate for Little Electric Chair

at $430,000 to $575,000. When Henry Wyndham, chairman of Sotheby’s Europe,

brought down the gavel, the room broke into applause. Little Electric Chair had

sold for $2.3 million.

The pink Little Electric

Chair—an iconic image from Warhol’s "Disaster" series, which also includes

car crashes and race riots—is considered one of the higher-quality prints in the

series, and the subject matter—capital punishment—is timely. Still, $2.3

million, four times the high estimate, was unheard of for a small

(22-by-28-inch), early Warhol print.

Observers were stunned by the

sale. "Everyone knew it would sell well," says Matthew Carey-Williams, a vice

president of contemporary art at Sotheby’s London (who has since transferred to

New York). "No one thought it would do as well as it did." Stellan Holm, a New

York dealer, who last spring held the biggest Electric Chair show in 30

years—15 of the original 40 prints, made in 1964—was impressed; he was on hand

to bid on Lot 17.

Members of Warhol’s former

inner circle were surprised as well. The dealer Ivan Karp, as director of the

Leo Castelli Gallery, represented Warhol and introduced him to many art insiders

when he was coming up in the early 1960s. "In the old days, we couldn’t sell

Electric Chairs at Castelli. They were considered disreputable," says Karp, who

is now director of the OK Harris Gallery in New York. In 1964 he sold one

Little Electric Chair for $1,800. When Warhol first showed them as a group

at a Toronto gallery in 1965, few people showed up at the opening, and there was

no press coverage.

At Sotheby’s contemporary-art

sale in New York in November, a yellow Little Electric Chair fetched $2.3

million, matching the record set in June. At Christie’s, a 1964 silk-screen

portrait of Holly Solomon sold for $2.1 million. Such prices prove that Warhol,

15 years after his death in 1987, has become the hottest commodity on the

contemporary-art market.

Warhol exhibitions are touring

the globe. A retrospective of 82 works, co-organized last year by the Andy

Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh and the U.S. Department of State, is appearing in

Eastern Europe, making Warhol the first contemporary American artist ever shown

in such countries as Kazakhstan and Latvia. Last year the Warhol Museum

organized 39 exhibitions and loans—as many shows as in the three previous years

together. What’s more, Warhol’s huge catalogue of films is being restored, and

many are being screened for a new generation from Pittsburgh to London.

In September Zurich dealer

Bruno Bischofberger, who was Warhol’s close friend and has been showing his art

since 1965, completed an exhibition of his 8-by-10-inch black-and-white

photographs, a large but little-known body of work. In New York last fall, the

Susan Sheehan Gallery presented a show of Warhol’s prints, drawings, and

sculptures from his famous "Shoe" series of the 1950s.

In October the New National

Gallery in Berlin launched a huge Andy Warhol retrospective, curated by the

Berlin-based dealer Heiner Bastian. The show, which will travel to the Tate

Modern in London this spring, includes not only early and late drawings but many

of Warhol’s most recognizable paintings and prints, as well as a retrospective

of his films.

Also in the spring, Phaidon

Press will publish the first of six volumes of the Andy Warhol catalogue

raisonné. The first two tomes will be edited by Georg Frei, a Zurich-based

dealer, and Neil Printz, a member of the board of the Andy Warhol Foundation for

the Visual Arts, who writes frequently about the artist. The Warhol Museum will

oversee the remaining four volumes. The project has been in development since

Warhol authorized the late Swiss art dealer Thomas Ammann to begin work on it in

1977.

Some observers believe that

Warhol’s reputation has profited from an increased interest in the period in

which he flourished. "A bigger percentage of the collecting world is now

interested in postwar art," Robert Mnuchin, of C&M Arts, says. "Warhol is at the

center of that." Thomas Sokolowski, director of the Warhol Museum, says that he

hasn’t seen this much interest in Warhol since the artist’s death.

Collectors are paying more for

Warhol’s work than ever. The art market had just peaked when Warhol died, and no

one imagined that his work would attract more attention than it did then. But it

has. "Warhol’s prices have risen drastically," says dealer Susan Sheehan, "much

more so than for any other artist." Just three years ago, Sheehan says, she sold

"Shoe" drawings from the 1950s for $5,000 to $12,000. Today they would fetch

$75,000 to $125,000. Ivan Karp agrees. "Warhol’s genuinely astounding prices

seem grotesque," he says. "They’re tainted with unreality."

In a recent article for

Artnet.com, Richard Polsky, a private San Francisco—based dealer who specializes

in post-1960 art, wrote that the $17.3 million Sotheby’s sale in 1998 of

Orange Marilyn was "the main event of the 1990s." It was, he wrote, one of

the events that helped jump-start the current Warhol renaissance. The price

shattered the 1989 auction record of $4 million, which belonged to Shot Red

Marilyn.

"With Warhol, it’s going to be

like Picasso," predicts Jeffrey Deitch of Deitch Projects in New York. "There’s

so much you can still do with Warhol, so many aspects—as a painter and as a

performance artist."

And as a photographer. In the

last two decades of his life, Warhol did many celebrity portrait series with his

Polaroid camera. In his classic in-your-face style, he shot everyone from

Muhammad Ali and Truman Capote to Jane Fonda and Dennis Hopper. Today these

photos, which measure 4 1/4 by 3 3/4 inches, have become collector’s items,

although many have begun to deteriorate. Eyestorm.com sold some for as much as

$9,000 apiece. A Polaroid portrait of Hopper went for $3,500 at Sotheby’s New

York in November.

The Warhol boom is also

manifesting itself outside the realm of art. The design for a new first-class

postage stamp featuring a 1964 self-portrait by the artist, from a photo-booth

snapshot now in the collection of the Warhol Museum, was unveiled at the

Gagosian Gallery in New York in November and will go on sale next summer. The

stamp’s selvage carries the Warhol quotation: "If you want to know all about

Andy Warhol, just look at the surface of my paintings and films and me, and

there I am. There is nothing behind it."

The exploitation of Warhol’s

images is becoming big business. Martin Cribbs, who is in charge of licensing

for the Warhol Foundation, says that "the number of requests for Warhol licenses

has definitely increased." In the last few years, he says, the foundation has

earned $800,000 in licensing fees and is projecting earnings ten times that

amount from deals that have just been signed.

Much of the licensing revenue

will come from a partnership announced in October between the foundation and the

Beanstalk Group, which promotes such brands as Coke, AT&T, and Harley-Davidson.

Beanstalk was named the exclusive licensing agent for the Warhol Foundation in

North America and Europe and will market products bearing Warhol’s images,

including dishes, bedding, and wallpaper, which will hit stores this month.

Other recent deals have led to advertisements for British Airways and

Mercedes-Benz, among other big corporations that have only just begun to take

advantage of the Warhol brand. These new licenses extend the product line far

beyond the generic museum-shop collectibles such as refrigerator magnets,

calendars, and stationery that the foundation had so far approved.

Warhol’s Montauk estate, which

he bought for $220,000 in 1972 with his friend and collaborator Paul Morrissey,

was put on the market last summer. The asking price for the 5.6-acre oceanfront

property has held fast at $50 million. In October Sotheby’s auctioned off

property and artwork from the estate of Frederick W. Hughes, who was Warhol’s

business manager for 25 years as well as the executor of his estate. The auction

raised $3.3 million, beating estimates. And in June the Pompidou Center in Paris

wrapped up a show titled "The Pop Years," which featured the actual tinfoil that

once lined the Factory, Warhol’s Manhattan studio.

Academics are seizing on the

current Warhol mania. The November issue of the journal October,

published by MIT Press, was devoted to critical and biographical essays on the

artist and his work. In September Warhol became the second visual artist to be

the subject of a Penguin lives Series book, written by the poet and English

professor Wayne Koestenbaum. The only other visual artist in the series is

Leonardo da Vinci.

When Warhol embarked on his

career in the 1950s, he wasn’t immediately taken seriously as an artist. Leo

Castelli originally refused to show his work, brushing him off as immature and

unoriginal. He became a sensation in 1964, when his Brillo boxes were shown at

the Stable Gallery. But by the time he died, newer, younger artists, including

the Neo-Expressionists, had eclipsed the aging former superstar. Today, however,

dealers are interested in the early and late works, as well as the midcareer,

iconic images, such as the portraits of Elizabeth Taylor and Mao Zedong and the

signature paintings of dollar signs and Campbell’s soup cans.

In 1958 the Museum of Modern

Art declined the donation of a "Shoe" drawing; Warhol had yet to attain the

notoriety of, say, Jackson Pollock or Robert Rauschenberg. But today the pre-Pop

works—the drawings of cats, fairies, and gold shoes, for example—are among the

most difficult-to-find items.

"We can’t find the early

material anymore," says Susan Sheehan. William S. Lieberman, chairman of

20th-century art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, says that of the 14 Warhol

paintings and 8 drawings owned by the museum, 4 of the most recent acquisitions

were early drawings.

"Because beginnings are very

important," says Mnuchin, "Warhol’s early work is very important."

"Before Warhol died," says

Andrew Fabricant, director of the Richard Gray Gallery in New York, "people

didn’t pay attention to his early work. Now that Warhol’s early work has changed

hands a few times, many pieces have increased in value." It was Fabricant who

bought the 1964 silk-screen portrait of Holly Solomon at Christie’s New York in

November.

Late works—the "Rorschach" and

"Camouflage" paintings, for example—are also much sought after. "His late work

was seen as flippant and commercial," says Fabricant. "Not anymore."

"Warhol was the most

undervalued of the Pop artists," says Vincent Fremont, who once worked for the

artist. He is now the exclusive dealer for paintings, drawings, and sculpture

for the Warhol Foundation. This spring the Gagosian Gallery in New York will

mount a show, curated with the foundation, of paintings Warhol did in the 1980s.

Warhol’s influence on younger

artists is greater than it was ten years ago. "Warhol was not as much an

inspiration as a liberator," says Ivan Karp. "He allowed for a new creativity."

He experimented with media, new printmaking techniques and Polaroids, for

example, as well as with subject matter: advertisements, newspaper headlines,

movie stars.

Sokolowski says that during

this summer’s Venice Biennale, "it was Warhol, Warhol, Warhol, everywhere you

looked." He points to the hyperreal sculpture of Ron Mueck and to video artist

Bill Viola, whose time-lag technique echoes Warhol’s film style. Says Sokolowski,

"Much of the thinking and production of today’s artists is very Warholian."

"For the past five years," says

Mnuchin, "there has been a broader recognition that Warhol is an important

artist." Fabricant goes farther: "It’s clear now that Warhol was one of the

greatest artists of the 20th century." For the first time since his death,

people are looking at his work in its totality.

"There has been a reevaluation

of how good Warhol’s [more obscure] art is," says Stellan Holm. That people are

buying lesser-known works is due in part to the fact that Warhol’s prices have

reached record highs. According to Fremont, it would have been impossible ten

years ago to do a show in the United States of Warhol’s drawings, because "there

just wasn’t enough interest."

Warhol was prolific; it was

said that he wanted to make more art than Picasso. ("I want to be a machine," he

famously remarked.) To suppress fakes, there is an Andy Warhol Art

Authentication Board, which considers the legitimacy of artworks attributed to

him. The six-member board is a private corporation, made up of curators, art

historians, and former Warhol associates, that was created with the Warhol

Foundation. Among its members are president David Whitney and secretary Neil

Printz. It meets three times a year to examine artworks submitted by Warhol

owners. It does not issue appraisals. Board members are unwilling to speak about

its activities, but, according to a source, 10 to 20 percent of the works

submitted to the board’s rigorous monthlong test are considered questionable.

Some observers feel that because Warhol often enlisted colleagues, lovers, and

collaborators to help him make art, many legitimate pieces made in the serial

manner have not been certified as authentic. Claudia Defendi, the board’s

assistant secretary, refuses to disclose details about how the board operates,

citing concerns about client privacy.

Because Warhol was so prolific,

there is a perception that a lot of high-quality work is still available, says

Polsky. "This is not true." Gallery owners, dealers, and auction houses agree

that the supply is beginning to dry up. "The Warhol market continues to get

stronger," says Leslie Prouty, Sotheby’s deputy director of contemporary art.

"But they are selling so well because they are hard to find these days." Mnuchin,

who presented a show last year of Warhol’s portraits of women, says, "There is a

small percentage of what we consider quality work. When supply gets taken out of

the market, prices go up."

Before he died, Warhol arranged

for the creation of the Warhol Foundation, whose primary business is grant

giving. (It earns revenue from licensing, the sale of art, and endowment

income.) The foundation’s biggest project was the Warhol Museum, which was

founded with a $2 million grant in 1990. In October Joel Wachs, a 30-year

veteran of the Los Angeles city council, took over as the new head of the Warhol

Foundation. Wachs, a member of the foundation’s board for six years, replaced

Archibald L. Gillies, who served as its first president.

In 1992 the foundation found

itself in a byzantine court battle brought on by Edward W. Hayes, who had been

the attorney both for Warhol’s estate and for the foundation, the estate’s main

beneficiary. The dispute involved the value of Warhol’s art. Hayes, claiming

that he was owed 2 percent of the value of the Warhol estate based on a contract

he had signed with executor Frederick Hughes, argued that Warhol’s body of work

was worth more than $700 million. Christie’s, which had been retained by the

foundation to appraise Warhol’s estate, put the sum at under $100 million. After

seven years of countersuits, Hayes was forced to file for bankruptcy and repay

the foundation some of what it had already paid him.

The foundation has been selling

Warhol’s work for 14 years. "It’s getting harder to do exhibitions for the

foundation," concedes Vincent Fremont. "There’s less material." This is in part

because after Warhol died, museums were given the first pick at around 50

percent of book value. The Warhol Museum owns more than 4,000 objects, the

largest collection of the artist’s work in the world.

"People didn’t see Warhol as a

visionary," says Fremont, from his office on Union Square, just a block from

where Warhol built his second Factory. "Now they do." Warhol was mute when it

came to discussing his art, Sokolowski explains. When he did speak, he was often

contradictory.

"People always cherished their

Andy," he says, whichever version of Andy they chose to know.

Tyler Maroney is a

Brooklyn-based writer. He is a former Fulbright Scholar.

The deathly double

His early

motto was 'I want to be a machine.' In his disembodiment, his voyeurism, his

strange vulnerability, Andy Warhol understood the deathliness of the mass image

better than anybody else. Hal Foster traces his life, work and symbolism

Monday March

18, 2002

Andy Warhol by Wayne Koestenbaum

Weidenfeld, 196 pp., 8 November 2001, 0 297 64630 3

In his account of late

capitalism Fredric Jameson describes its cultural logic as if it were a

schizophrenic - broken in language, amnesiac about history, in thrall to glossy

images, subject to mood-swings from speedy euphoria to catatonic withdrawal. No

wonder that his exemplar is Andy Warhol. "Warhol distrusted language," Wayne

Koestenbaum writes on the first page of his smart biography; "he didn't

understand how grammar unfolded episodically in linear time, rather than in one

violent atemporal explosion. Like the rest of us, he advanced chronologically

from birth to death; meanwhile, through pictures, he schemed to kill, tease and

rearrange time."

Signs of this linguistic

disturbance, real or staged, are abundant. There is "virtually no correspondence

in his hand": photographs, audiotapes and films were his modes of inscription.

He couldn't spell to save his life: typographic errors recur in his commercial

illustrations of the 1950s, sometimes introduced by his Czech mother, Julia. And

he spoke in a deadpan that extended to his books, which were mostly edited from

taped conversations. All of this evidence leads Koestenbaum to his initial

diagnosis of Warhol: "Trauma was the motor of his life, and speech the first

wound" - speech understood here as the medium of 'normal' intersubjectivity or

reciprocity with the world.

'Trauma' is the lingua franca

of much cultural analysis today, and it is not new to Warhol studies either.

From his mother's colostomy bag (she had colon cancer) to the brutal scars that

tattooed his torso (he was shot, almost fatally, in June 1968), wounds figure

literally in Warhol. A 1960 painting, based on a newspaper ad for surgical

trusses, asks prophetically 'Where is Yo Rupture?', and Warhol always seemed to

pick out the telling cracks in images and in people, whom he often regarded as

another species of image. Metaphorically, too, as a breaching of interior and

exterior, trauma can be seen as the very operation of his art. "It's just like

taking the outside and putting it on the inside," Warhol said early on about

Pop, "or taking the inside and putting it on the outside."

This elliptical remark might be

understood literally - at one point Koestenbaum interprets his "entire oeuvre as

an externalisation, crisply distanced and disembodied, of his abject internal

circuitry" - or again metaphorically, with his Pop images seen to register the

delirious confusions between private and public that first became pronounced in

this era: that is, between the desires and fears of the individual subject and

the commodities and celebrities of consumer society, of which Warhol was the

great portraitist. In either case he appeared 'porous' in a strange, new,

near-total way: porous both in his art, with its steady stream of Pop effluvia

(from his early Campbell's Soup Cans to his late Diamond Dust Shoes), and in his

life, with his studio, dubbed 'the Factory', set up as an open playground for

subcultural denizens, mass-cultural divas, and 'superstars' of his own making.

At the same time Warhol was the

opposite of porous. Especially after his shooting by the paranoid Factory

fade-out Valerie Solanis, he countered his vulnerability with psychological

defences and physical trusses of different sorts: buffering entourages, opaque

looks (big glasses, silver wigs), protective gadgets (the omnipresent Polaroid

and tape recorder), plus a weird ability to pass as his own double or simulacrum

(even when he was right there in front of you he seemed somehow disembodied).

And these devices became

central to his persona, which is sometimes seen as his ultimate work: Warhol as

the spectral centre of a flashy scene, a kind of blank Gesamtkunstwerk-in-person.

Whereas Marshall McLuhan, a very different media figure of the 1960s, viewed new

technologies as prostheses, Warhol used them as screens. As Koestenbaum writes,

the dominant strategy of his Pop was to combine "lurid subject" and "cool

presentation", and to translate images from one medium or sphere into another in

order to "embalm" them - though this embalming could also infuse his images with

a psychic charge, an unexpected punctum, as Roland Barthes might say. Think of

the two housewives in Tunafish Disaster (1963), victims of botulism taken

directly from a newspaper page; smeared across the silkscreened painting, their

smiling faces become piercing in repetition.

From the early days of the

Factory on, Warhol always recorded: visitors were often placed in front of a

movie camera in a 'screen test' that also served as an initiation rite. And

especially in his last years he collected compulsively: when the going got

rough, Warhol went shopping, and his townhouse became filled with sets of

kitschy things like cookie jars which were auctioned off after his sudden death

in 1987. For Koestenbaum, this endless taping-and-filming and buying-and-bagging

point to a subconscious plan to "conquer by copying" or to control by gathering.

Here what counts as 'putting in' or 'taking out', as porous or trussed, open or

closed, is not clear, but that may be the point: like the two states that

underlie them, these two strategies are bound up with each other. In this light

his collecting was another way of being porous to the world, and his being

porous another way to defend against images and objects - that is, to drain them

of affect, to close them off again.

His sayings on this score are

well known: from his early motto, "I want to be a machine," to his late ode to

repetition, "I like things to be exactly the same over and over again... Because

the more you look at the same exact thing, the more the meaning goes away, and

the better and emptier you feel." Perhaps it was to this same end that, after

1974, he diarised the bric-a-brac of his life in 'time capsules', cardboard

boxes filled with mementos and ephemera (there were over 600 in his estate). In

a nice twist Koestenbaum adopts a nickname that Warhol dropped early on, 'Andy

Paperbag', which evokes not only his compulsion to collect but also the

fragility of this protective device. More ominously, he writes of the Campbell's

Soup Cans and Brillo Boxes as "simulacra of Andy's body". Deleuze and Guattari

gave us the 'body without organs', the subject as a machine of desirous

connections; Warhol left us with its quasi-autistic opposite, the 'box without

openings'.

Koestenbaum also relates the

proclivity for "multiplication and archiving" to gay taste in New York, which in

"the bleak McCarthy era paradoxically flourished in the home". In this "domestic

avant-gardism" public signs were ironised in private ways that "interrupted the

distinction" between the two spheres. Such customising of images is close to

'camp' as defined by Susan Sontag. Alert to the queer dimension of this

sensibility (her celebrated 1964 essay reads in part like a field report on the

gay underground of Warhol, the filmmaker Jack Smith and others), Sontag saw camp

as "dandyism in the age of mass culture" - that is, as a way of wresting the

distinctive from the vulgar, of finding feeling in kitsch, of transcending "the

nausea of the replica".

Some of this spirit, such as

the attraction to degraded imagery, is maintained in Pop, but much is not: Pop

hardly redeems sentiment, and it does not transcend the nausea of the replica so

much as rub our faces in it. Here Koestenbaum shifts the lines that have long

defined Warhol studies, away from breaks in style such as Abstract Expressionism

v Pop, and towards (dis)continuities in sensibility across his campy commercial

work of the 1950s and his cool artwork of the 1960s.

Trained at the Carnegie

Institute of Technology (now Carnegie-Mellon), Warhol moved from Pittsburgh to

New York in 1949, and shed his ethnic identity then, too, dropping the final 'a'

from his name. He fared well as a commercial illustrator, with adverts done for

Harper's Bazaar, Seventeen, the New Yorker and Vogue, displays for Bergdorf

Goodman, Bonwit Teller, I. Miller and Tiffany & Co., as well as book jackets,

record covers, stationery and the like. Warhol received three Art Directors Club

awards in the 1950s, and he continued in this mode well into the 1960s - an

often overlooked fact - through 1962, when the Campbell's Soup Cans appeared;

1963, when the films began; 1964, when the Brillo Boxes were done; and so on.

Moreover, as Koestenbaum argues, Warhol was "more of a fine artist in the 1950s"

as a commercial illustrator than in the 1960s as a Pop artist, if by 'fine' we

mean the apparent signs of craft, handwork and subjective expression.

And the reverse is also true:

his great silkscreens begun in 1962 show a "designer's intelligence", and, as

Benjamin Buchloh has written, his Pop art carries over traits of his commercial

illustration: "extreme close-up fragments and details, stark graphic contrasts

and silhouetting of forms, schematic simplification and, most important,

rigorous serial composition". The imbrication of the two practices was

persistent: his first show of Pop paintings was a window display at Bonwit

Teller in 1961, and after 1968 he returned to a mode that he never really left -

"business art". Until recently, art history has mostly glanced over the

commercial design in some embarrassment (at least Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper

Johns had the good taste to treat their window displays as rent-money work),

sidelined the films and bemoaned his supposed decline after the 1968 shooting.

Along with a few other contemporaries, Koestenbaum writes against all three

biases.

Until recently, too, art

history liked to suggest a clean break between the aftermath of Abstract

Expressionism and the rise of Pop, and it pounced on a particular anecdote to

firm up this stylistic divide. In 1962, Warhol showed two paintings of a Coke

bottle, first to the filmmaker Emile de Antonio, then to the dealer Ivan Karp,

and asked them which he should exhibit. (This is a classic instance of his

deferring of responsibility. Marcel Duchamp exacerbated the problems of artistic

making and judging with his ready-made objects: "Whether Mr Mutt made the

fountain or not had no importance. He chose it." Warhol complicated aesthetic

choice further by passing it off, or at least around, often to his assistants.)

One of the Coke paintings has painterly drips that might read as signs of

expressive gestures, while the other is almost as pristine as the commercial

original, right down to the registered trademark. His friends opted for the

iconic Coke, and Pop was born. Although now sealed with the false obviousness of

history, this story was always too convenient by half. Even more blatantly than

his gay predecessors Rauschenberg and Johns, Warhol derailed Abstract

Expressionism stylistically (though it had also run out of track by then); the

crucial question is what drove this turn.

Here another juxtaposition,

made by Rosalind Krauss, is telling. In the early 1960s Warhol continued the

drip paintings of Jackson Pollock by other means: he peed onto canvases which

were covered with metallic paint and set on the floor - or had his Factory

workers pee (even here he deferred). The paint oxidised into misty veils or,

when his female associates peed, murky puddles. These paintings 'queered' the

drip paintings: suddenly the machismo of the Pollock gesture looked a little

impotent, and the homosocial dimension of the old Abstract Expressionist circle

like a circle-jerk (primal boys peeing on fire). The piss paintings also forced

a double-take on the apparent purity of Colour Field painting, on the poured

veils of Morris Louis and the stained grounds of Helen Frankenthaler; and when

Warhol did more such works in the late 1970s, Neo-Expressionist painting looked

even more absurd than it did before.

As critics such as Douglas

Crimp and Richard Meyer have stressed, this queering of art was also a matter of

content. If the persona behind Abstract Expressionism was the 'action painter'

in existential torment, Warhol put pretty-boy idols of mass culture up front,

such as the young Troy Donahue and Warren Beatty, Elvis and Brando, all subjects

of early silkscreens. More notoriously, he did the same with the not-so-pretty

Thirteen Most Wanted Men, the FBI mug-shots that he silkscreened for the facade

of the New York State Pavilion at the 1964 World's Fair (they were covered up by

order of Commissioner Robert Moses, who was not amused when Warhol offered to

substitute an image of him instead). Here he turned the meaning of 'most wanted'

inside out: these men might be 'wanted' sexually, too - might be 'criminals' in

a double sense.

The queering did not stop

there. As Annette Michelson argues, the Factory was a semi-conscious mockery of

Hollywood cinema and culture industry alike. For instance, in many Warhol movies

'montage' means the simple splicing together of unedited rolls of film (Empire,

made in 1964, is a fixed stare at the Empire State Building that lasts for 24

hours); few have stories, let alone scripts, and some are porn. Moreover,

Michelson sees the Factory as a latter-day experiment in Bakhtinian reversal:

with its "parodistic procession of divas, queens and superstars", and

spectacular mixing of uptown society, 42nd Street riff-raff and downtown

bohemia, it resembled a court turned into a carnival. "In carnival," she writes,

"behaviour and discourse are unmoored, as it were, freed from the bonds of the

social formation. Thus, in carnival, age, social status, rank, property, lose

their powers, have no place; familiarity of exchange is heightened."

The strategy of the Factory was

indeed 'super' - to hyperbolise roles in a way that sometimes mocked them. But

this parodistic play with the social order was only half-intended; it was also

sporadic and short-lived, and by the time of the Interview magazine of the

Reagan years it had swung over to its opposite: hero-worship of the rich and

famous. So, too, the tropes of carnival, "travesty and humiliation" above all,

often rounded on Factory dwellers; as Koestenbaum suggests, this scene could

also be cruelly hierarchical - very different from the cosy milieu of the

commercial-illustration days.

Koestenbaum sees both

continuity and discontinuity here: even as the Factory "extended the apartment

philosophy Warhol first learned from decor-conscious gays", it diverged from the

campy sensibility of his design studio. In his Diaries (1989) Warhol refers this

break to the death of his favourite cat in the early 1960s: "My darling Hester.

She went to pussy heaven. And I've felt guilty ever since... That's when I gave

up caring." This is a mock-traumatic account, of course; affect did not die with

Pop, but it did take on a torturous turn in the Factory. This is so in part

because the Factory was given over to 'performance' in the sense not only of

performance art (all the screen tests and films, the live theatre and 'Exploding

Plastic Inevitable' events featuring the Velvet Underground) but also of

performed identity.

"To work for Warhol was to lose

one's name," Koestenbaum comments; and Billy Linich, the de facto manager of the

Factory, became 'Billy Name', as Robert Olivio became 'Ondine', the heroine of

a: a novel (1968), Susan Hoffmann 'Viva', the star of several films, and so on.

This renaming was one prerequisite to superstar status, and it was often bound

up with regendering: to 'swing both ways' was to play with both semiotic and

sexual designations. This was the carnivalesque moment par excellence, and it

had obvious risks, especially when mixed with pill-popping and vein-poking,

bohemian showmanship and media spotlights.

In short, there was a

psychological volatility of roles in the Factory, which sometimes sounds like a

desultory S/M theatre, with Warhol as a director both kind and cold, passive and

aggressive. He would goad people into defensive or outlandish performances,

especially in the films (some of which also thematise bondage), as if to film

was to provoke and to expose, and to be filmed was to parry this attack.

Koestenbaum is good on this "emotional oscillation"; he catches the tension

between inhibition and excess, "diffidence and exhibitionism", deathly stillness

and sexual motility, and argues that it could induce a "paranoid relation" to

whomever acted out on the screen or in the Factory at large. But the movies also

produce a different sort of connection: the viewer does not identify with the

filmed subject in the manner of classic Hollywood cinema, of course, but rather

empathises with the travails of being before a relentless camera, with the

vicissitudes of becoming an image, with wanting or resisting this condition too

much.

According to Koestenbaum,

Warhol always had a particular target in his sights - masculinity - and a

particular way to mess with it, which he terms 'twinship'. "Masculinity was a

subject Warhol failed from the start," Koestenbaum writes; his art became "the

sexualised body his actual body largely refused to be". In this regard, too,

"Andy liked to entrust others with the task of embodying Andy," and often this

embodying involved "female dopplegangers" like Edie Sedgwick whose ambiguity as

both femme and boyish did a number on gender. Koestenbaum refers this 'twinship'

to a "homoerotics of repetition and cloning", but it might also be seen as a

play with kinds of likeness that are only like enough to be subversively other.

This doubling-with-a-difference

runs throughout Warhol: both in his life, where he was mirrored, weirdly, by

Edie, Nico and others; and in his art, where the silkscreens are often instances

of image repetition run amok, and the films are often double projections in

which the 'action' in one screen has little or nothing to do with that in the

other. Koestenbaum describes this trait as "nonparticipatory adjacency", and in

a sense it structured the entire Warhol world: he spent days at the Factory with

image-producers and scene-makers; evenings first at the bar-and-restaurant Max's

Kansas City and later at the club Studio 54 with the entourage; nights at home

on the Upper East Side with Mom and the cats; and Sundays at Mass (he remained a

Catholic to the end).

At first Warhol projected onto

celebrities; later he painted them; in time "he merely needed to stand next to

them... his Andyness could sign the adjacent presence, make it Andyish." Here,

too, doubling was the primary Warholian device. (For me it became delirious one

night in the early 1980s at a club called Area, as I watched Jean Baudrillard,

the theorist of the simulacrum, watching Warhol posing as 'Warhol' in a bare

diorama of his own making, as if he were the wax model of his own dead specimen.

I thought one of them would have to explode.) "Pop art rediscovers the theme of

the Double," Barthes once wrote, but it has "lost all maleficent or moral

power... the Double is a Copy, not a Shadow: beside, not behind: a flat,

insignificant, hence irreligious Double."

I'm not certain about this last

point. In the Factory Warhol was called 'Drella', a fitting contraction of

Cinderella and Dracula, for like the former he lived the dream of going to the

ball (and sometimes getting the prince), and like the latter he sucked the blood

of others in a way that left him ravished too. This deathly doubling is one

reason why Warhol remains so fascinating: more than anyone else he acted out the

strange mass subjectivity of the Pop image-world. As Michael Warner has argued,

"to be public in the west means to have an iconicity... In the figures of Elvis,

Liz, Michael, Oprah, Geraldo, Brando and the like, we witness and transact the

bloating, slimming, wounding, and general humiliation of the public body. The

bodies of these public figures are prostheses for our own mutant desirability."

Warhol operated on both sides of this equation: he was a "mutant desirer" first

and last, but he also became a mass icon in his own right; indeed after his

shooting he entered the pantheon of martyr-stars (Liz, Marilyn, Jackie) that he

also portrayed.

Like Christ (here Koestenbaum

stretches for a parallel too far, but why not?), Warhol became more iconic as

his body became more ravaged. He took on a "revenant appearance", and delivered

works possessed of "the shadow aura of bulletins from the afterlife", paintings

of Skulls (1976) and Shadows (1978) in particular; appropriately, he was at work

on a wallpaper version of the Skulls - portraits of us all in effect - at the

time of his death. Unlike the Pop of Roy Lichtenstein or James Rosenquist, his

Pop had teeth, and a great part of its edge lay in its recognition of the

deathliness of the mass image. On this score the best remark comes from Deleuze

in 1969, in the middle of the Vietnam war, no doubt with Warhol in mind:

"The more our daily life

appears standardised, stereotyped and subject to an accelerated reproduction of

objects of consumption, the more art must be injected into it in order to

extract from it that little difference which plays simultaneously between other

levels of repetition, and even in order to make the two extremes resonate -

namely, the habitual series of consumption and the instinctual series of

destruction and death. Art thereby connects the tableau of cruelty with that of

stupidity, and discovers underneath consumption a schizophrenic clattering of

the jaws, and underneath the most ignoble destructions of war, still more

processes of consumption. It aesthetically reproduces the illusions and

mystifications which make up the essence of this civilisation, in order that

Difference may at last be expressed."

· Hal Foster is Townsend

Martin Professor of Art at Princeton. Design and Crime is forthcoming from

Verso.