Perdita: the life of Mary Robinson

Paula Byrne HarperCollins, 477pp, £20

ISBN 0007164602

Reviewed by Edwina Currie

|

4-6-2005

Mary Darby Robinson

(1757 - 1800)

|

|

Perdita: the life of Mary Robinson

Reviewed by Edwina Currie

|

|

Click to enlarge

No, no. Not that Mary Robinson. This one lived roughly

200 years earlier than the former Irish president and was a high-class tart. And

successful author. And remarkable woman, though for most of her life she was no

lady.

We have met her before. She appears, briefly, in Amanda Foreman's Georgiana,

Duchess of Devonshire, the book that started the vogue for "tart-hist"

(that's the history of posh tarts to you). She flitted through Katie Hickman's

Courtesans and featured in Anna Clark's Scandal. She popularised

see-through muslin dresses and necklines cut so low that the breasts were on

display. Indeed, cartoons of Robinson show her mostly with her skirt up, her

bosoms out, and having a rare old time, usually with the Prince of Wales or

Charles James Fox, or some other admirer.

In the days when "rake" and "womaniser" were regarded as natural epithets for

any man about town, Robinson was kept busy. In return, she obtained a bond of

£20,000 from the future George IV (equivalent to nearly £1m today), jewels,

carriages, a house in Berkeley Square and Parisian fashions that dazzled

society. George Romney, Thomas Gainsborough and Joshua Reynolds painted her

portrait for free. Newspapers and scandal sheets reported her every move; ladies

of the town rushed to ape her manners and her style.

The daughter of a failed businessman and the dupe of a lying hound of a husband,

Robinson supported her family by going on the stage, aged 14, as a protegee of

David Garrick. She must have been gorgeous, especially with her legs on show in

the breeches parts so common in Shakespeare. Critics recognised her outstanding

beauty, but also praised her acting ability in a number of roles. In 1779, the

teenage Prince of Wales went to Drury Lane to see Garrick's adaptation of The

Winter's Tale, and was smitten. She was the first of his many mistresses.

His lovesick letters, signed "Florizel", named her as "Perdita" for life. They

also provided her with ample opportunity for blackmail.

Then, as now, more sober voices were raised. A letter signed "Lover of Virtue"

complained of the Morning Herald that

whole columns of it are filled with Mrs Robinson's green

carriage. It is of little

consequence to the public whether [she]

drives four ponies or two coach-horses;

whether she paints her neck or her cheeks; whether she sports a phaeton or rides

in a dung-cart; whether she is accompanied by a peer or a pimp . . .

The press invented euphemisms: Robinson

and her cronies were the Cyprian Corps (Venus, goddess of love, was said to hail

from Cyprus), or the frail sisterhood, the vestals "and 20 other pretty names".

The prince soon tired of her, but was replaced by "Butcher Tarleton" (who gave

the Redcoat army a bloody reputation in America) and by Fox, who switched to her

rival Mrs Armistead - his "dearest Liz" - whom he later married. Robinson, by

now pregnant by the absconding Tarleton and short of funds, raced off to

Brighton to pursue him to France. But she never arrived. At some point during

the coach ride, she lost the baby and was stricken with what seems to have been

rheumatic fever. She was never again able to walk properly. No more was she a

fabulous actress and courtesan.

The rest of her life, until her death at the age of 43, is to some extent an

anti-climax, and she must have felt it as such. She published poetry, much of it

under the influence of laudanum and Coleridge. But in 1792 came her first novel,

Vancenza; or, the Dangers of Credulity. A Gothic romance, it contained

thinly veiled references to the sexual predilections of the prince, and was a

literary sensation. Mrs Robinson was off again.

Paula Byrne appears to have read everything written about or by Robinson, and

analyses each paragraph at inordinate length, lifting the literary veils and

showing who is who - not difficult, as her subject's outpourings were largely

autobiographical. Heaven help anyone who, 200 years from now, tries it with my

stuff. If Robinson was as intelligent as Byrne claims, she would be hugely

amused at such industry, and might even feel it her due; but 430 pages is a

great deal for someone whose main claim to fame - that she gave pleasure to

famous men - was so fleeting.

Only in the 1990s was Robinson rediscovered by the feminists, who were trying to

rewrite the history of Romantic literature, highlighting those female authors

whom patriarchal history had airbrushed out. Yet given a choice between the

working girl and the bluestocking, I'd far rather have the former. A feminist

icon Robinson cannot be, and her poetry has deservedly bitten the dust. But her

story - particularly the early, dazzling part - makes highly enjoyable

entertainment for us today.

Edwina Currie's Diaries 1987-1992

are published by Time Warner Paperbacks

LINKS:

Bibliography by Prof. Laura L. Runge

Bibliography by Kristen Chancey

Reviews in the Analytical Review, probably by Mary Wollstonecraft

WORKS

Robinson, Mary, 1758-1800: Letter to the Women Of England, on the Injustice of Mental Subordination (with commentary) (HTML at UMD)

Robinson, Mary, 1758-1800: Lyrical Tales (HTML at UC Davis)

Robinson, Mary, 1758-1800: Memoirs of Mary Robinson, also by Mary Elizabeth Robinson (illustrated HTML at Celebration of Women Writers)

Robinson, Mary, 1758-1800: Poems, by Mrs. M. Robinson (1791) (HTML at Celebration of Women Writers)

Robinson, Mary, 1758-1800: Sappho and Phaon

· Online Archive of California

· illustrated HTML at Virginia

Robinson, Mary Elizabeth: The Wild Wreath (HTML at UC Davis) - written by her daughter

The TLS n.º 5309 January 7, 2005

THAT WOMAN HAS AN EAR

Nora Crook

Paula Byrne

PERDITA

The life of Mary Robinson

477 pp. HarperCollins £ 20 (US $27.50)

0 00 716460 2

Hester Davenport

THE PRINCE’S MISTRESS

A life of Mary Robinson

256 pp. Sutton, £ 20

0 7509 3227 9

|

Mary Robinson (1757-1800) was

among the most celebrated literary

|

|

Robinson discovered a new

Humphrey Leadenhead and Lady Upas jostle with tragic heroines who muse “Oh,

sensibility! thou curse to woman! thou bane of all our hopes, thou source of

exultation in our tyrant man!”. But her fictions have a mutinous, theatrical

energy; it was principally their “Jacobin” and “Rights of Woman” tendencies that

made them obnoxious in the late 1790s.

In 1791, Robinson had appealed to the National Assembly of France, writing

(unlike Burke) as a friend of the Revolution and (unlike Paine) in support of

Marie-Antoinette, whom she regarded as viciously calumniated. Under

Wollstonecraft’s influence she became one of the foremost “champions of her

sex”. Her vigorous Letter to the Women of England (1799) advocates a “masculine”

university education for women and the right to duel. Becoming increasingly

crippled, she retired to the cottage orné of her beloved daughter, cultivated

friendship and the maternal affections, carried on as poetry editor of the

Morning Post and articulated her ideal of assembling a “little colony of Mental

powers”. What strikes one forcibly is the absence on her part of any pious

remorse for her sinful past. She resembles Jane Austen’s Mrs Smith in

Persuasion, who, similarly invalided after a youth of frolics, sustains herself

by her “elasticity of mind”.

Both bring their subject and her context to life, but Paula Byrne offers the

fuller picture: Perdita is almost twice as long as The Prince’s Mistress, and

the research is deeper and more wide-ranging; it is the nearer to being a

literary biography and will perhaps help to bring more of Robinson’s writings

back into print. The bibliography includes e-texts. Looking up of endnotes is

inconvenient (why don’t more publishers use running heads for the note section?)

and a final edit could have screened out some untidy repetitions and small

discrepancies, but it is a very fine and pleasurable biography. Hester

Davenport’s is straitened in comparison, but it is deftly written; it includes a

checklist of Mary Robinson’s theatrical roles and vivid glimpses of the men she

went for.

Spotting

Perdita

Paula

Byrne gives Mary Robinson, scandalous darling of the 18th-century stage and

letters, a welcome rebirth in Perdita

Lisa O'Kelly

Sunday December 5, 2004

The Observer

Perdita: The

Life of Mary Robinson

by Paula Byrne

HarperCollins £20, pp477

Click to enlarge

Mary was born in Bristol in 1757 or 1758 (the vagueness is typical of her; she managed her image carefully). The only daughter of a prosperous merchant, she was unusually well educated for a girl at that time but before she reached her teens, her father disappeared to Canada with his mistress and spent all the family's money. Finding a solvent husband for Mary became her mother's priority. At the age of 15, Mary was married to Thomas Robinson, a trainee solicitor with apparently good prospects.

But he had lied about his circumstances and he, Mary and their baby daughter were soon in a debtors' prison. When they were released, Mary set about repairing their fortunes. Within months, she had transformed herself into a celebrated actress under the wing of David Garrick, although her success was perhaps due more to her beauty and charm than to any dramatic talent.

Witty and flirtatious, Mary soon made friends in high places. Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire was a lifelong friend and patron, as were Sheridan and Coleridge. At 21, she played Perdita at Drury Lane in Perdita and Florizel, Garrick's adaptation of Shakespeare's A Winter's Tale. The 17-year-old Prince of Wales, later to become George IV, was in the audience and fell in love with her. Mary began an affair with him that catapulted her to the very pinnacle of celebrity.

Even when the affair ended, Mary, now known as Perdita, was feted as a great beauty and fashion icon. She introduced London to the sexy, loose-fitting, empire-line muslin gown with broad ribbon sash that was to remain fashionable until the Victorian era. There was a 'Perdita hood', a 'Perdita handkerchief' and a 'Robinson hat'. There were 70 celebrity portraits painted by Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough, George Romney and others.

But despite her fame, Mary was short of money - she had given up acting at the prince's request and her husband was a feckless gambler. So she held George to ransom, threatening to publish his love letters if he did not pay her an annuity.

When Mary was left partially paralysed in her late twenties, her star waned. Yet she remade herself as a poet, novelist, journalist and essayist. She also became involved in politics through a friendship with Charles James Fox. Paula Byrne makes a strong case for Mary's importance as a poet and novelist. But it is as an essayist and commentator that she is most interesting.

She used her public platforms to air the radical themes of the day, protesting against slavery and social injustice and arguing for university education for women. Mary Wollstonecraft became a firm friend and admirer and Byrne argues convincingly that Robinson's Letter to the Women of England on the Injustice of Mental Subordination deserves as much attention as Wollstonecraft's A Vindication of the Rights of Women.

You could argue that Byrne spends too little time on this part of Mary's life and too long on her early days. Yet maybe that is as it should be. Mary embraced all aspects of life and was ashamed of nothing that she had done. Coleridge coined a fitting tribute to her: 'I never knew a human being with so full a mind - bad, good, and indifferent, I grant you, but full, and overflowing.'

There's

something about Mary

Frances Wilson delights in accounts from Sarah Gristwood and Paula Byrne of the

royal mistress, actress and poet Perdita

Saturday

January 29, 2005

The Guardian

Perdita: Royal Mistress, Writer, Romantic

by Sarah Gristwood

409pp, Bantam, £20

Perdita: The Life of Mary Robinson

by Paula Byrne

480pp, HarperCollins, £20

After a century of silence, three competing lives of the 18th-century actress, courtesan and writer Mary Robinson have arrived (Hester Davenport's The Prince's Mistress was published recently by Sutton). For Robinson, such a deluge of publicity would fail to raise an eyebrow; dubbed "the most beautiful woman in England", her every movement was documented in the press, her image plastered everywhere, she read her own obituary 14 years before she was due to meet her maker and her Memoirs had to contend for the truth with a fictitious, salacious memoir written in her name.

When it was unheard of for a middle-class woman to be celebrated for anything, Robinson achieved celebrity in three separate spheres, giving her life not a single peak of success but a series of separate summits. She was famous first as a Drury Lane actress, trained and supported by the luminaries of the day, Garrick and Sheridan. During a performance of The Winter's Tale, Robinson caught the eye of the juvenile Prince of Wales (who, aged 17, was three years younger than our own Prince Harry), after which she had the dubious honour of being his first mistress - the notorious "Perdita" to his "Florizel". Although the titles of Sarah Gristwood's and Paula Byrne's books commemorate this brief period in Robinson's life, they each recognise that the affair with Florizel was one of the least significant of Perdita's achievements, its importance lying in the pressure the prince exerted on the actress to give up the stage (which, reluctantly, she did) and the pressure she then put on him to compensate her with a lifetime's annuity (which, reluctantly, he did).

After she was abandoned by HRH and her own feckless husband disappeared, Robinson was kept by the Whig politician Charles James Fox, for whom she campaigned. She then settled into a tempestuous, 15-year relationship with Colonel Banastre Tarleton, a celebrity-soldier who, according to Gristwood, "gave muscle to her glitzy, slightly showbiz fame". "One yearns to say," writes Gristwood, that the couple were "the Posh and Becks of their day". While pursuing Tarleton on a coach to Dover, Robinson was struck down with the mysterious condition - which both biographers agree to be a violent attack of rheumatoid arthritis - which rendered her immobile. Not yet 30, for the last decade of her life Robinson had to be lifted, wheeled and carried everywhere. It was then that she became a writer - and a very successful one - of novels, political tracts, essays, plays, and reams and reams of poetry. The former show-girl now mixed with the intellectual heavyweights of the day, William Godwin, Mary Wollstonecraft and Coleridge (who, Gristwood argues, was terrified of the older woman's evident sexuality and transgressive past).

Gristwood's Perdita: Royal Mistress, Writer, Romantic and Byrne's Perdita: The Life of Mary Robinson might be regarded as the literary equivalents of the famous Gainsborough and Reynolds portraits of Robinson, both painted in 1782. Gainsborough's lush and languorous study of beauty recently scorned by royalty was thought good to look at but not a good likeness, while Reynolds's cool, grave, urban seductress is considered to have captured more Robinson's remarkable strength. Gristwood, like Gainsborough, understands the business of image control. Writing about Robinson, she focuses on the peculiarities of the public persona, recognising the same quality she found when, as a journalist, she wrote about modern celebrity; that "odd blend of wariness and avidity with which she regarded any attempt to know her". Her Robinson is, she argues, a prototype of Madonna, a "media baby", a mercurial, material girl who "spent most of her life in a state of fame", and were she to make a programme on Robinson, Gristwood writes, she would want to interview Max Clifford. Byrne's Robinson is the more stable and cerebral figure, "a thinking woman of real genius". She may have been sexually transgressive and a fashion icon, but it was as "a novelist, satirist and social commentator that Mary's true talents lay".

While Gristwood is good on context, particularly the French revolution and the social position of courtesans, Byrne has done more extensive research and has the edge on the killing detail. Her major scoop is finding the original manuscript of Robinson's Memoirs , which reveals subtle, telling differences from the published version. Byrne has a grasp of the 18th-century stage which Gristwood, who is more interested in analogies with 20th-century show-business, does not; the strongest pages of Byrne's excellent biography are those which describe Robinson's years at Drury Lane. The early period of Robinson's life is also more detailed in Byrne; she argues convincingly that Perdita was involved with the money lender "Jew King" before her liaison with the prince, as well as being the mistress of the royal best friend, Lord Malden.

Both biographies argue that Robinson's place in romanticism has been apallingly erased, but while Byrne is a scholar of romanticism, Gristwood is a student. Byrne writes about the literary scene of the 1790s with authority while Gristwood leans on other authorities (Janet Todd, Richard Holmes, Tim Fulford) to validate her points. Both write about Robinson's opium-dream poem, "The Maniac", dictated to her daughter, but it is Byrne who makes the stronger case for Robinson's being the precursor of the romantic tradition of opium-inspired writing. Gristwood, for her part, writes of the origins of Coleridge's trance-like "Christabel" that it would be "too facile a temptation for the biographer of Mary Robinson to suggest that the combination of guilt and guiltlessness Coleridge perceived in [Robinson] provided the poem's inspiration", but she suggests it none the less.

Of these very different books, each a fascinating and stimulating portrait, Gristwood's might be described as the "racier" and Byrne's as the weightier. Byrne has had the good fortune of a Richard & Judy nomination, so will undoubtedly be the more widely read. But as the many paintings of Mary Robinson show, she lent herself readily to more than one perspective.

Frances

Wilson's The Courtesan's Revenge is published by Faber.

Perdita: Royal mistress, writer, Romantic by Sarah Gristwood, Bantam

Take Posh, and Madonna, add a dash of the Princess of Wales, plus Linda Evangelista...

Suzi Feay examines the extraordinary life of an actress-courtesan turned author who was an early celebrity casualty

Published : 30 January 2005

Beauty being so perishable, it is a quality impossible to grasp and define after two centuries. Charles II's bevy of mistresses in the National Portrait Gallery look like so many fat-cheeked and double-chinned slatterns. The incredible story of Perdita - Mary Robinson - is impossible to understand without a notion of the haunting beauty that set it all off.

Examine the portraits and they all seem to show different women, and not necessarily, by our standards, beautiful ones. In some she has a decidedly long nose. She can look voluptuous, ethereal or merely pert. They were rarely recognised as good likenesses in their day. Joshua Reynolds was one painter who confessed himself utterly defeated by her dazzling looks.

Mrs Robinson was one of the most admired, reviled, painted and written about women of the 18th century. The phrase "actress, model, whatever" is a modern one, but Perdita was the ultimate "whatever". She couldn't go shopping without a press of people materialising around her. Her exploits were written up in the gutter press; her clothes were scrutinised and copied. Sarah Gristwood can't quite resist the urge to call Mary and her lover Banastre Tarleton "the Posh and Becks of their day" (though as she points out, there are also dashes of Madonna and Princess Diana). And, much as visiting football fans sang pornographic chants about Mrs Beckham, she became the focus of scurrilous prints, fantasies and bawdy verse.

By her mid-teens the stunning Mary Darby of Bristol had come to London and captivated (purely professionally) the renowned actor Garrick, who wanted to put her on the stage. She married the useless gambler and wastrel Robinson but once on the boards came swiftly to the attention of the Prince of Wales (the future George IV). She was playing Perdita in The Winter's Tale; he promptly dubbed himself her Florizel, and pursued her hysterically. She was his first great passion, and set the pattern for all the others. He was clinging, fond and babyish. There was no warning of the final breach; the last time they met as lovers, he was as ardent and attentive as ever. Then the lightning bolt fell. She was ruined and dumped by the prince before she was even out of her teens, and her attempts to get a fair settlement from him make for grim reading. The man who acted as go-between, Viscount Malden, became her new protector. From this point it seems Mary was little more than a courtesan: definitely shop-soiled, but still an object of goggling fascination for the masses.

"Who'd not love a soldier?" runs the speech bubble in a Gillray cartoon entitled The Thunderer, where an effigy of Mary, legs akimbo, dangles above an inn-sign ("Alamode beef, hot every night"), while a muscular soldier slices the head off a figure, the plumes of blood forming the Prince of Wales's feathers. Yes, Mary had a new lover, Banastre Tarleton, a hero (from the British point of view) of the American War of Independence. The Americans called him "Butcher Tarleton", and Gristwood, a respected film journalist, points out that if he seems like a black-hearted Brit villain in a Mel Gibson movie, that's because he is one: the sadistic killer played by Jason Isaacs in The Patriot was based on Tarleton.

In her memoirs, later in life, Mary presents herself as a devotee of the cult of sensibility, too sensitive ever to thrive in this cruel world. Tarleton, by contrast, was an old-fashioned pig (so old-fashioned, in fact, that he was still doughtily defending slavery at a time when "Am I Not a Man and a Brother?" had become the fashionable rallying cry). Gristwood tells a horrifying story of their first meeting, culled from the pornographic supposed "Memoirs of Perdita", which nevertheless contain significant facts about her life. Her long-term lover, Malden, offered a jeering Tarleton 1,000 guineas if he could seduce her. For that, Tarleton could both seduce her and jilt her, he claimed; and Mary woke up in the small village out of town to which his passion had swept her to find that he had left her with the bill. A humiliated Mary couldn't pay, and applied to Malden, the source of all the trouble. He refused to help her out.

Naughty Diva

Reviewed by Meryle Secrest

Sunday, August 14, 2005; BW09

PERDITA

The Literary, Theatrical, Scandalous Life of Mary Robinson

By Paula Byrne

Random House. 445 pp. $27.50

The life of Mary Robinson provides an object lesson in a problem that chronically afflicts biographers. Here is an amazing story, that of a girl with modest prospects who makes her mark as an actress, dabbles in poetry, writes novels and plays and becomes mistress of the Prince of Wales -- and all of this before dying at the age of 43. Such accomplishments would be startling in any epoch. Yet she did it in the 18th century. "Perdita," as she was called (after her most famous role), was well enough known to be the subject of cartoonists and the favorite model for such portraitists as Hoppner, Romney, Gainsborough and Reynolds.

A snap, one would think, to write about. Yet 200 years later nobody knows who she is. This makes it all the more unusual that a book like this has been published. More often, no publisher would take it, or the advance would be minuscule, the work arduous and sales disappointing. Only someone not easily deterred would persevere in such a situation, particularly since gathering facts about such a life is even more akin to looking for the right pebbles on a beach than most biographical exercises. A labor of love, one might conclude. Yet without such punishing, almost masochistically arduous work, the Mary Robinsons of this world would disappear into obscurity.

That would be a pity since, as Paula Byrne demonstrates, a patient search can give us a more intimate insight into a woman and her epoch than contemporary readers could otherwise imagine. Byrne paints an unforgettable picture of the prosperous, grimy port of Bristol, where Robinson was born, and of her father, who left his wife and three children to establish a fishery in the Canadian north. How this abandoned wife managed to go on paying the bills is the kind of question to which the author bends her mind. How a girl of that period had to think is also something that Byrne addresses sympathetically. Obviously, this young woman could not afford to marry for love. But after the security she sought in her one and only marriage proved to be a chimera, Mary, with a baby in tow, voluntarily joined her spendthrift husband in debtor's prison.

Forced to become the major breadwinner, Robinson turned to writing, one of the few respectable avenues for young women in that epoch. Her poetry, almost unreadable nowadays, was nevertheless admired enough to be published, and gained her a patron in the person of another independent spirit, Georgiana, duchess of Devonshire. Robinson had a gift for attracting distinguished supporters, not just because she was a beauty but also because she was full of life and brimming over with talents just waiting to be discovered by older and wiser mentors. The playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan was entranced with her; so was the actor David Garrick. While still in her teens, she was cast in demanding roles and made an immediate impression. One concludes that she was either a natural in everything she did or a fast study, and both are probably true, because the ease with which she maneuvered her way into the worlds of art and society is otherwise inexplicable. She charmed. She performed. She found ways to dress beautifully and set fashions so convincingly that she rivaled the great Georgiana herself.

The steps by which Robinson, a struggling young married woman with baby, became a notorious young actress with no visible baby or husband and lots of lovers are amusingly detailed. Byrne describes a number of protectors, some more handsome than others, before "Perdita" made her most famous conquest in the young Prince of Wales, the future George IV. Seeing her on the stage, he fell in love with this vision when he was just 17. How much love played a part in her response is an open question. She certainly made the most of her opportunity, incidentally securing a national role for herself in the sometimes scurrilous cartoons that followed her. There were more lovers, more theatrical triumphs, more books and, at the end, a memoir. The admirable skill with which her biographer winds through this turbulent progression is a treat to read.

One must add a caveat: The author's ear for style has a way to go before it reaches the level of her erudition. Nothing is more contagious for someone immersed in the writings of a bygone period than the style itself. And so we have such quaint anachronisms as "repaired to Bristol" and "Considered in this light, his commitment could not be doubted" -- phrases that look doubly stilted when placed against modern slang. There are other lapses; incorrect use of words and some completely impenetrable phrases make one wonder where the editor was.

Still, Perdita is not just an important addition to our knowledge of history but also a highly enjoyable story, told with much care and insight. Brave, witty, dashing and gifted -- such women speak to any age. ·

Meryle Secrest, author of the recently published "Duveen: A Life in Art," is working on a biography of Modigliani.

Sunday, March 27, 2005

Perdita

Royal Mistress, Writer and Romantic

By Sarah Gristwood

BANTAM PRESS LONDON; 409 PAGES; $33.57

Perdita

The Literary, Theatrical, Scandalous Life of Mary Robinson

By Paula Byrne

RANDOM HOUSE; 445 PAGES; $27.50

Twenty years ago, a biography of writer Mary Robinson would have been impossible. Feminists -- and academia in general -- had no interest in the scribblings of an 18th century actress, royal mistress, flamboyant courtesan and fashion icon. Never mind that she repackaged herself as a political radical. It was impossible to take her seriously, especially when less sexy and harder-thinking heroines such as Mary Wollstonecraft were at hand.

A re-examination of Mary Robinson's work has finally removed her from the status of dabbler to the center of the Romantic canon. Her "Lyrical Tales" are now read alongside Wordsworth's and Coleridge's "Lyrical Ballads," validating Coleridge's opinion of her as a "woman of undoubted Genius. ... I never knew a human being with so full a mind -- bad, good, & indifferent, I grant you, but full, & overflowing."

Not one but two absorbing biographies have placed her back in the public eye, where she always longed to be. (A third biography was published in the United Kingdom last year.) Not bad for the daughter of a bankrupt ship captain who abandoned his family, leaving them to shift as best they could.

Shift Robinson did, though not always to her advantage. At the age of 15 or 16 -- both biographers are unsure of her birth year -- she married a ne'er-do-well, convinced by his lies that he stood to inherit a fortune. It was the first of her many regrets. His dissolute lifestyle landed them in debtor's prison, where she produced her first volume of poetry, hoping it would bring in a little money.

Robinson's dazzling literary success would come later. She first triumphed on the stage under the tutelage of David Garrick and Richard Brinsley Sheridan. Playing the role of Perdita in "The Winter's Tale," she soon became involved in a public affair with the Prince of Wales (the future George IV), making her a media celebrity. Thomas Gainsborough and Joshua Reynolds were just a few who painted her, her likeness never the same, and not one ever said to truly represent her. Then again, how could one painter capture her every side?

Opportunistic, melodramatic, a creature of deep feeling and lightning- quick thought, she possessed tremendous strength when faced with adversity, which was often. When the prince abandoned her for a rival courtesan, Mary did not step aside lightly. There was a question of a bond he had given her, and she still possessed his love letters, for which his irritated father, George III, paid at today's value $700,000. There would be other men, but none she loved more than the hard-fighting, high-living Col. Banastre Tarleton, newly returned from America (and the model for the sadistic Col. Tavington played by Jason Isaacs in Mel Gibson's "The Patriot"). One of the more compelling dramas of her life included a late-night coach ride to stop Tarleton from leaving the country to escape his creditors. A mysterious illness struck her down during the journey, and gradually, she lost the use of her legs.

Her beauty ravaged by her illness, Mary turned to writing to make her living. She had always penned anonymous, flattering paragraphs about herself for the newspapers, and in effect, she was still writing about herself. She looked at her own life for ideas, which offered ample material. Her first novel would sell out in a day. Eventually, her anger over the double standard for female behavior drew her toward radical thinkers, and she counted as friends Coleridge, William Godwin and Wollstonecraft. All the while, her body of work grew while she wrote at a feverish speed to earn money.

Consequently, not all of her work is good, but as Paula Byrne explores in "Perdita: The Literary, Theatrical, Scandalous Life of Mary Robinson," much is valuable. Byrne, an academic, excels at tracing Robinson's literary development and analyzing her output. However, her assessment that Mary originated opium-inspired poetry stems more from wishful thinking than proper judgment of the evidence.

That's easily forgiven. Byrne writes with remarkable knowledge of period nuances and delivers spot-on observations. She convincingly understands what went on inside Robinson's head as wife, actress, mistress and writer. For instance, she tells us that Robinson's "obsession" with fashion wasn't about frivolity. Instead, Robinson was "attuned to the ways in which clothing could transform her image." Byrne shows a critical eye for detail, making it all the more curious that she did not spend more time in the archives researching Robinson's earlier life. For the most part, her research is first rate, but her book could have been even better than it already is.

Sarah Gristwood, in "Perdita: Royal Mistress, Writer, Romantic," likewise neglected opportunities to reveal more telling moments from Robinson's life. Her research is not as deep as Byrne's, but what she doesn't know, she instinctively grasps. It is through Gristwood that Robinson lives. While Byrne knows more, Gristwood knows better -- at least, up until Mary Robinson becomes intellectually driven.

Gristwood offers the vivid, tangible woman, making Byrne's Robinson seem almost, but not quite, static by comparison. Gristwood, so aware of Robinson as a sensuous being, is exquisitely in tune with her subject's Romantic sensibilities. It is a shame that she occasionally references 21st century celebrities, but nonetheless, she stirs the senses with a novelist's eye, connecting with Robinson on an emotional level that Byrne does not, nor is interested in doing. Byrne is drawn to Robinson the thinker. Her Robinson is less passionate but more observant, grounded and, ultimately, has more scope.

Alas, Gristwood loses some of her sparkling momentum toward the end of Robinson's life when writing about the literary world of the 1790s. (Robinson died in 1800 at the age of 42 or 43.) This is truly Byrne's area. Hers is an important literary biography, though it is far more than that. Byrne is too smart to limit her heroine. Gristwood's book might best be described as a romantic biography. Both are engaging, in different and wonderful ways. It might be fair to say that Byrne has ownership over Robinson's mind. Her body and soul, however, belong to Gristwood.

Biographer Martin Levy edited the memoirs of Mary Robinson, "The Memoirs of Perdita" (Peter Owens).

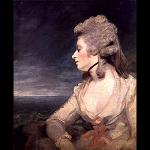

Mrs Mary

Robinson: Perdita, Thomas Gainsborough (c1781)

Jonathan Jones

Saturday August 26, 2000

The Guardian

|

Artist: Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788), who started out painting squires, their wives and rural Suffolk before becoming one of London's most fashionable portrait painters. Subject: Mrs Mary Robinson (1758-1800), an actress who caught the eye of George the Prince Regent when she was playing Perdita in The Winter's Tale in 1779 and became, briefly, his mistress. Distinguishing features: Perdita sighs her time away in nature's bower, with only her loyal dog and a miniature portrait of her lover for company in the weeping woods. She's attractive in her grief; her silk dress and powdered face are immaculate. The folds of her dress merge with soft green foliage and her features are brilliantly set-off by the dark woodland shadows. The landscape seems designed to show her at her best, as indeed it was - Gainsborough certainly did not paint her in a real natural setting. The story of Perdita, however, is a seedy one. The Prince Regent, in between building his Royal Pavilion at Brighton and stuffing Carlton House with art treasures, went from mistress to mistress. He was quite the romantic at the beginning of his relationship with Mrs Robinson. Seeing her on stage as Perdita, he sent her a miniature of himself - the one she languidly holds in her right hand - with a paper heart inside swearing love forever. |

|

|

|

Click to enlarge

She became his first famous mistress. But by the time he had commissioned Gainsborough to provide a keepsake of the affair, he had discarded her amid bitter recriminations. In 1785 George was to secretly marry Mrs Fitzherbert. George later presented this painting as a gift to the Marquess of Hertford, whose wife happened to be his current mistress.

Gainsborough's portrait is not a study of character - he's happy to take Mrs Robinson at face value and celebrate her as a famous beauty. He is a jeweller among artists, a supremely decorative painter whose attention to surfaces is spellbinding. He almost always painted portraits, usually in rural settings. His art developed from early Suffolk landscapes in which the gentry pose slightly awkwardly to sumptuous harmonies of body and landscape.

Although the Prince Regent paid for this tall, grandly-scaled picture, it seems to be Mrs Robinson who has determined its pose in a way that communicates her plight in various subtle ways. Perdita is in a pastoral retreat, nursing her wounds. She has been exiled to an autumnal landscape where the hues are brown and muted. The wind-buffeted trees are echoed in her own fragile, willowy figure and suggest the blows she has sustained. She communicates her loyalty to George - she's like the patient dog - and her desire is evoked by the mysterious shadows of the woods.

Inspirations and influences: Gainsborough's rustic refinement takes its erotic woodland ambience from the French rococo painter Antoine Watteau (1684-1721), who painted fetes galantes, in which masked revellers flirt in decorative woods. Perdita merges with an eroticised nature like the lovers in Watteau's Departure from the Island of Cythera. Gainsborough provided the justification for portrait painters at the turn of the 20th century like John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) to depict people with a near-abstract decorative freedom such as his pastoral portrait Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose (1885-6).

Where is it? The Wallace Collection, Hertford House, Manchester Square, London W1 (020-7935 0687).

Women’s rights movement in England -- 2nd half of 18th Century

Mary Scott (Taylor) (1752 - 1793)

, The Female Advocate; a Poem (1774)

Mary Wollstonecraft

(1759 - 1797), A Vindication of the Rights of Woman

(1792); Maria, or, The Wrongs of Woman (1798)

Mary Matilda Betham (1776-1852), “The Power of Women” (1798)

Priscilla Bell Wakefield (1751-1832), Reflections on the Present Conditions of the Female Sex; with suggestions for its improvement (1798)

Mary Hays (1760-1843), An Appeal to the Men of Great Britain in Behalf of the Women (1798)

Mary Darby Robinson (1757 – 1800), A Letter to the Women of England, on the Injustice of Mental Subordination (1799)

Mary Anne Radcliffe (1746- after 1810),

The Female Advocate; or, an attempt to recover the rights

of woman from male usurpation (1799)